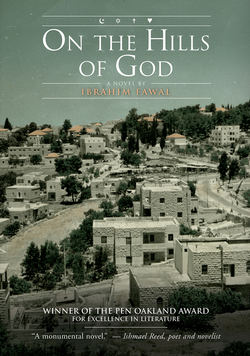

Читать книгу On the Hills of God - Ibrahim Fawal - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеWearing well-pressed pants and short-sleeved sport shirts, Yousif and his friends, Amin and Isaac, were out for their ritual Sunday afternoon stroll. Yousif was Christian, Amin Muslim, Isaac Jewish. They were born within a few blocks of each other. They had gone through elementary and secondary school together. Together they had switched from short to long pants, learned to appreciate girls, enjoyed catching birds, suffered over acne, and, because they were all Semites, wondered who among them would have the biggest nose. They were so often together that the whole town began to accept them as inseparable.

Yousif, considered by many to be the leader of the three, was tall and had a thick black head of hair. He was first in his class, many considered him handsome, and no one doubted that he was relatively rich, being the only son of the most popular doctor in town. Amin was short and compact, with a perfect set of gleaming white teeth and skin that was a shade darker than the other two. He was the oldest of nine children and the poorest of the three companions: for his father was a stonecutter and all his family lived in a one-room house in the oldest district in town. Isaac was of medium height, with high cheekbones, sunken cheeks, and a shy, winsome smile. His father was a merchant who sold fabrics, mostly to the villagers who came to shop in the “big” city, in a store he had inherited from his father.

None of the three boys wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps. Yousif wanted to be a lawyer; Amin a doctor; Isaac a musician. Such were the dreams that fluttered in their hearts as they walked together, like birds awaiting the full development of their wings to fly.

That afternoon these three were enjoying a favorite Ardallah pastime: tourist watching. Ardallah was a town thirty miles northwest of Jerusalem and fifteen miles east of Jaffa. Tourists made the population of this summer resort swell from ten thousand in the off season to nearly double that during the summer, and to perhaps twenty-two thousand over the weekends. Ardallah swarmed with automobiles and pedestrians. There were occasional camels and mules, which, however archaic, were still viable means for moving goods. Pushcart vendors weaved from one sidewalk to another, undaunted by the heavy traffic or by the angry, sometimes rhythmic honking from drivers who were not above coupling their blasts with a few choice words or obscene gestures. The many little shops—and the few big ones—did a thriving business. Shoppers coming out of the Muslim and Jewish stores had their arms laden with packages. But to the Christian shopkeepers of this predominantly Christian town, Sunday was truly a day of rest.

On that particular Sunday, the three boys nudged each other in anticipation as they saw a group of nine tourists descend from the Jerusalem-Ardallah bus, which stopped at the saha, the main clearing at the entrance of town.

Normally such an arrival would have drawn little or no attention, for the sidewalks were crowded with strangers and the outdoor cafe across the street was jammed with locals and chic tourists luxuriating under red, yellow, and blue umbrellas sparkling in the bright Mediterranean sun. But the newcomers who had just stepped off the shining yellow bus were noticeable for their conspicuous good looks and identical khaki clothes. A couple of the men had cameras strapped to their shoulders; a third had what seemed like a flask of water strapped around his neck. The attractive young women wore shorts that displayed legs and thighs, clashing sharply with Muslim women, who hid their faces behind black veils. For although the great majority of the Arab women in town did wear modern western dresses, most were on the conservative side, and quite a few still wore the traditional ankle-length and heavily embroidered native costumes. The most stylish, even daring, of the Arab women wore short sleeves, or knee-length skirts, or low-cut dresses. Any spirited female dressing in this fashion invited tongue wagging and faced the possibility of a fight with her husband or father or brothers. Such was the society into which these nine tourists entered. Their bronze-deep tans and the generous exposure of female flesh drew some lecherous looks and good-natured whistles. Even the four tall handsome men accompanying them, who carried duffle bags on their backs, wore shorts, and had their sleeves rolled up on their brown muscular arms. The group became self-conscious and laughed, and the spectators laughed with them. So did Yousif and his two friends.

“I think they’re Jewish,” Yousif said.

“Who cares?” Amin glowed. “Seeing them here is better than taking a half-hour ride to Jaffa to watch them swimming on the beach.”

“They’re Jews, I tell you,” Yousif insisted, as if Isaac were not there.

“They could be English,” Amin told him. “We have a lot of them around.”

“I don’t think so,” Yousif argued. “Only the Jews speak Arabic with that guttural sound. I heard one of them say khabibi instead of habibi.” He knew that the mispronunciation of the h was the shibboleth that most quickly set Arab and Jew apart.

Isaac laughed. “The Jews I know don’t have that sound. I say habibi just as well as you do.”

Yousif looked surprised. “I meant Jews who were not born and raised here, the recent immigrants—”

“I know what you mean,” Isaac said, his eyes following the scantily clad arrivals. “But I think it’s Yiddish.”

“You think? Don’t you know?”

“I speak Hebrew—but the few words I caught sounded Yiddish to me.”

The three boys trailed the exotic group down a sidewalk crowded not only with pedestrians but with men playing dominos or backgammon in front of shops. Passing magazine stands and tables laden with leather and brass goods, the boys followed the strangers all the way from the Sha’b Pharmacy right up to Karawan Travel Agency, the only travel agency in town. Arm in arm, the men and women looked like close friends.

Yousif envied them. He bit his lip as he saw one of them hug the waist of the girl walking next to him. He wished he could put his arm around Salwa.

Three blocks from the bus stop, two of the tourists stopped and bought multi-colored ice cream cones from a pushcart at the corner of one of the busiest intersections in town.

“Are you thinking what I’m thinking?” Amin asked, rubbing his hands.

“What are you thinking?” Yousif asked.

“That we’re not trailing just boyfriends and girlfriends on a Sunday stroll?”

Isaac looked at him and scratched his chin. “Who are we trailing then?”

“Lovers,” Amin grinned. “Lovers intent on serious business.”

“You’re crazy,” Isaac told him, disinterested.

“You’ll see,” Amin said. “Before long they’re going to be on top of each other. And I’m going to be there watching. Yousif, what do you think?”

All his life Yousif had heard that Jewish girls were promiscuous, and these women seemed even more loving than most. Were the stories he had always heard about them true? Was it true that the girls of Tel Aviv had seduced many an Arab man? Supposedly they would romance them for a weekend and leave them dry.

Bearing this in mind, Yousif found it entirely possible that these attractive and healthy-looking men and women were lovers looking for a place to camp and make love, that they had come to consummate their passion in the seclusion of Ardallah’s wooded hills.

“It’s hard to say what they are,” Yousif answered finally.

“Look what they’re carrying,” Amin replied with conviction. “What do you think they have in those canvas bags on their backs?”

“You tell us,” Yousif said.

“It’s obvious,” Amin said, bumping into a pedestrian but not losing his thought. “They’re carrying blankets. That’s what they need for outdoor sex, isn’t it?”

Isaac shook his head. “I think your parents had better find you a wife before you embarrass them.”

They all laughed and continued walking, jostling others so as not to lose sight of those they were trailing.

The strangers were heading toward Cinema Firyal. There was a chance Salwa might be attending the matinee. If she were, Yousif would try to convince his friends to go in, and while they watched the screen, he would content himself with watching Salwa, even from a distance. Damn it, he thought; why couldn’t Arab society allow those in love to walk or sit together in public?

Because he was in love, Yousif suspected that the whole world was in love: either secretly or publicly, as in the case before him. He looked for a touch, a glance, a word and construed them as definite signs of an affair. To him, summer was the season for love, and Ardallah was the ideal place.

Only Ramallah, a town fifteen miles to the east and a better-known resort, surpassed Ardallah in the number of vacationers who arrived every summer. They came to either town from every corner of Palestine, sometimes from as far as Egypt and Iraq. The affluent stayed at hotels, but most rented homes for the long duration. From the north they came from Acre; from the south from Gaza. They came to Ardallah from the seashores of Jaffa and Haifa, and from the fertile fields and orchards of Lydda and Ramleh. They came with their children and grandchildren. They came wealthy or simply well off. But they never came poor.

Summer in Ardallah, Yousif knew, was meant for the elite who could afford it. It was meant for those who preferred it to Lebanon, or were not lucky enough to find a room in Ramallah, those who wanted to slip away for the weekend from the sweltering weather on the Mediterranean coast, or had not yet discovered Europe.

Ardallah sat as a crown on seven hills from which could be seen a spectacular panorama of rolling hills and, on a clear day, a glimpse of the blue Mediterranean waters. Ardallah was close enough to the big cities, but small enough to have its own charm. It was not exactly a playground for the rich, but an oasis for the young and the aged and all those in between who cared for the cool fresh air and the soft invigorating breeze.

Ardallah had over ten schools (different ones for boys and girls); five churches (one big Greek Orthodox, one big Roman Catholic, one small Greek Catholic, two tiny Anglican); one mosque; five hotels (renowned for their spacious wooded gardens); and three cinemas. The highest building was three stories, built of chiseled white stone, as were all the houses that were scattered over the mountain slopes. Some of the new homes had all the conveniences of the modern world. Such luxuries were important not only because the new owners desired them and could afford them, but because most of these homes were let during the summer months to the vacationers who insisted on hotel-type accommodations.

Except for fruit trees in private gardens, the trees around Ardallah were primarily cypress and pine. Perhaps it was these trees that had conspired with the geographic location to give the town its glory. But they said it was the Ardallah breeze that most attracted tourists—the gentle caressing breeze that blew against one’s skin like a mother’s breath. Built 2500 feet above sea level, Ardallah was a natural landmark. Between Ardallah and the Mediterranean Sea lay Jaffa, Lydda, and Ramleh, which were surrounded by hundreds of orange groves; between Ardallah and the highlands lay hundreds of Arab villages surrounded by fig and olive groves and pasture lands, where shepherds could still be seen sitting atop a hill playing the flute or herding their flock as in biblical times.

Ardallah had always welcomed her guests. Yousif himself waited nine months a year for their return. He loved the change and the excitement that resulted from their appearance. They brought their fashions, their gaiety, their dialects, the glamour of their women in their latest fashions or fancy cars, and their money, which made everyone in town walk around with a smile. The tourists slept in the morning, drank tea and ate fruits on their verandas, and played backgammon or bridge in the afternoon. And, yes, they danced at night.

Often Yousif would go with his parents to these hotels and meet the rich families and powerful men his parents knew. How lovely the women and their daughters were, Yousif remembered. The women of this upper class did not abide by old-fashioned restrictions; they swayed under the moonlight to the tango and foxtrot and waltz tunes played by orchestras—often imported from places as distant as Athens and Rome.

Often Yousif would dance with their daughters. The colored lights which had been hung outdoors over the dance floor would shimmer, the dresses of the elegant women would rustle, and Yousif, dressed in the conservative manner of his father, would wish Salwa and not his mother or some stranger’s daughter were in his arms.

On two occasions the previous summer he had been fortunate enough to have danced with Salwa herself, and to have given her a peck on the cheek when the dance floor was overcrowded and no one was looking. The smell of her hair and the feel of her body burned in him for weeks and still lingered in his mind. This year luck might smile on him again; at least he hoped.

By the time the conspicuous strangers reached Bata, the famous shoe store, Yousif was jolted out of his daydreaming. What triggered his suspicion was the large amount of equipment they were carrying. What did they need all the canvas bags and the cameras and binoculars for? And what about that tripod under the tall man’s arm?

It struck Yousif that they were carrying surveying equipment. This new perception was anchored in the depth of his being and born out of many nights of listening to his father and his father’s friends discuss the mounting tension between the Arabs and Jews. Should hostilities break out, as some expected, what these outsiders were doing could prove detrimental to the Arabs. Such preparation, he reasoned, could mean the difference between victory and defeat.

“My favorite is the tall blonde,” Amin said, his brown eyes dancing. “The one with the long shapely legs.”

“I bet you wish she had her arms around your waist,” Isaac taunted.

“Do I!” Amin swooned.

“How far are we going to follow them?” Isaac asked, elbowing his way through the crowd.

“Until we find out what they’re up to,” Yousif said, his mood changing. “They could be Zionists.”

“So what?” Amin asked, impatient. “What’s a Zionist anyway? Some kind of a weird Jew, isn’t he? Isaac, are you a Zionist?”

“You’re crazy,” Isaac said. “Of course I’m not a Zionist.”

“Don’t get angry, I’m just asking. Well, is your father a Zionist?”

“No one in my family is a Zionist,” Isaac explained, wiping his glasses with his handkerchief.

“Well, do you know what a Zionist is?” Amin pressed.

Isaac looked around. “He’s a member of a political party. Most Zionists are Jews, but not necessarily. They’re just members of a party, like any other political party. They have their aims and goals and ideology. Isn’t that right, Yousif?”

“That’s what I’ve heard.”

“Okay,” Amin said, keeping his eyes on the tourists. “They are members of a party. But what do they want?”

“To take over Palestine,” Yousif told him. “They think it’s theirs. They think God promised it to them.”

“And what about us? We’re Abraham’s children too. Just like them.”

“They want us out,” Yousif told him.

“Out where?” Amin inquired.

“I don’t know. Just out.”

Amin looked at Isaac, grinning. “Now you tell me who’s crazy. Me or them. Well, if they’re that cuckoo, let’s follow them for sure.”

Yousif kept his eyes on the strangers, who were stopping now to look at the variety of sweets and pastries. He restrained Amin and Isaac from walking any closer lest anyone become aware that they were being followed. The tall dark man with the sinewy arms who was accompanying the blonde with the bluest eyes bought two portions of red-colored cheese-filled kinafeh wrapped in waxed paper. Three others, including the statuesque brunette in her thirties who reminded Yousif of Salwa, bought dark roasted peanuts from a tall, thin, Ethiopian woman selling from a portable stand that emanated smoke.

“Where do you think they’re going?” Amin inquired.

“I have a feeling they’re headed for the woods, but not for what you’re thinking,” Yousif said, stepping off the curb and holding back his friends to let a car make a right turn.

“They’re heading west,” Yousif explained. “There’s nothing in that direction except the olive and fig orchards. There must be more comfortable places to make love than a rocky field. Besides, I just don’t believe they’d screw in broad daylight with everyone watching.”

“Well I hope you’re wrong and I’m right,” Amin said, again rubbing his hands. “If I catch them in the act, I think I’ll go crazy.”

“Don’t worry, you’re not about to,” Yousif told him, leaning against a wall to count the strangers ahead of him. “Look, there are nine of them. Who’s going to make love to the odd number? I tell you they’re not lovers.”

The new suspicion seemed to destroy Amin’s confidence in his own theory.

“What a bore,” he said, “but I still would like to know for sure.”

The strangers were half a block away from the entrance to Rowda Hotel’s garden. Maybe, Yousif thought, they would turn to go in and bask in the shade of the ancient trees. But the strangers passed the entrance without even turning their heads and proceeded to descend the hill, going west. The three boys looked at each other again, then began to follow them in earnest. They maintained a respectable distance from the strangers and, to avoid suspicion, chose to walk on the other side of the street.

On the outskirts of town, the group paused at a main fork in the road. One of them looked back and saw Yousif and his friends. Then all of them turned around and looked in the direction of the three boys. Yousif quickly bent down to tie his shoelaces, and Isaac and Amin stopped and waited for him to finish.

“They saw us,” Yousif muttered as he tightened the lace through every hole.

When he looked again the group had split up and gone in two different directions. Yousif rose and the three boys resumed their walking. They agreed to stay together, but didn’t know which group to follow. By the time they reached the fork they decided to follow the group of five that had turned right and taken the dirt road.

The group ahead of Yousif and his friends moved briskly, doubling the hundred meters between the two groups. They had to walk much faster to keep up with them.

As the straight road ended and dipped into the valley Yousif could see the Roman arch, a landmark two-thirds of a mile away. Beyond it was a steep hill, a narrow road, and vast fields of olive and fig trees which stretched over several mountains. Yousif was alarmed.

“If they get to that arch before us,” he told his two friends, “they could disappear very easily and we’d never find them.”

Isaac frowned. “I’ll be damned,” he said, kicking a stone.

“I know a short cut,” Amin suggested. “But we’ll have to run. Are you willing?”

“Yes,” Yousif and Isaac said together.

“Let’s go then,” Amin said, starting to run across the field to his left.

Yousif and Isaac ran behind him, leaping over small stone walls and ducking under tree branches. A bush tore a small hole in Isaac’s trousers and a pebble caused Yousif’s ankle to twist under him as they tried to catch up with Amin, who had struck out ahead of them and was now racing down the hill like a gazelle chased by two foxes. Five minutes later, they reached the Roman arch, confident that they had beaten the strangers. They hid behind the thick columns and waited, wiping sweat from their faces and around their necks.

Yousif could soon hear thudding footsteps. He had to take a chance and look. He raised himself up and checked the road. He saw a farmer walking behind a burdened mule and heading toward town, singing.

They have erected mountains between you and me.

But what could stop the souls from reaching out across the mountains.

The three friends had to suppress a giggle. Did the sight of the handsome couples put the farmer in such a romantic mood? Then Yousif was distracted. He focused on the “lovers.” One of the men raised the binoculars to his eyes and inspected the mountain. Another took out a map which he and the striking blonde at his side hunched over.

“I tell you they’re up to no good,” Yousif said, turning toward Amin and Isaac.

Suddenly, Yousif’s eyes fell on a shiny round object lying on the ground. The sun hit it at the right angle and made the silver gleam. He was sure it was a watch. He picked it up and rolled it in his hand, disappointed. “It’s a compass,” he said.

“A compass!” Isaac exclaimed. “Let me see it.”

Yousif handed it to Isaac, knowing that it had fallen from the strangers they were following. His earlier suspicions deepened; he was now convinced that they were surveying the hills. He turned around to tell Amin. To his surprise Amin was standing on the edge of a large rock. In his white shirt, Yousif thought, Amin might as well have waved a flag.

“Get off that rock,” Yousif told him, his voice hushed.

In answer, Amin stepped closer to the edge and craned his neck to see where the couples went.

“Get down,” Isaac warned, his hands cupping his mouth.

Amin did not seem to pay attention, but stood looking for a better spot. He stepped down on an adjacent wall, and it gave under him. The stones toppled, creating a roaring sound that could have been heard from a distance. Yousif and Isaac leaped to catch Amin, but it was too late. He rolled down the hill with large and small boulders crashing around him. His friends gasped and then ran after him. When the avalanche stopped, Amin lay sprawled at the bottom of a field, one huge rock on top of his left arm.

“Jesus!” Yousif said, frightened.

Yousif looked at Amin, then at the strangers. His loyalty was divided. He didn’t want to see Amin hurt but he also didn’t want to lose the strangers. Had they been regular tourists, he thought, they would have come back to help. Surely they must have heard the sound of the stone wall collapsing. He watched in frustration as they hurried around a bend in the valley and disappeared.