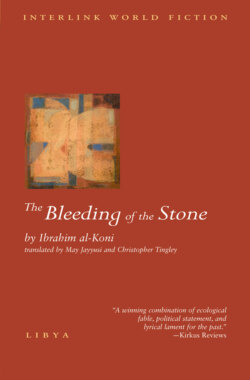

Читать книгу The Bleeding of the Stone - Ibrahim al-Koni - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1. THE STONE ICON

There are no animals on land or birds flying on their wings, but are communities like your own.

—Quran 6:38

And it came to pass, when they were in the field, that Cain rose up against Abel his brother, and slew him. And the Lord said unto Cain, Where is Abel thy brother? And he said, I know not: Am I my brother's keeper? And He said, What hast thou done? The voice of thy brother's blood crieth unto Me from the ground. And now art thou cursed from the earth, which hath opened her mouth to receive thy brother's blood from thy hand; When thou tillest the ground, it shall not henceforth yield unto thee her strength; a fugitive and a vagabond shalt thou be in the earth.

—Genesis 4:8-12

It was only when he started praying that the male goats decided to butt one another right there in front of him.

Evening was coming, the flaming disk of the sun sinking slowly down from the depths of the sky as it bade farewell, with the threat to return next morning and finish burning what it hadn't burned today, and Asouf plunged his arms into the sands of the wadi to begin his ablutions, in readiness for his afternoon prayers. Hearing the roar of the engine from afar, he decided to hurry and give God His due before the Christians arrived, so as to be ready as usual to welcome them to the wadi and show them the figures painted on the rocks.

But Satan entered the goats, who took evident pleasure in butting at the very moment he said “God is great” and began murmuring the Fatiha,i as if they were proud of their horns or wanted to show him their skill. They were restless today because a skittish she-goat had led on a headstrong male. He'd been following her since the morning, probing her rear with his nose, trying, incessantly, to climb up on her from behind, and this had aroused the jealousy of the other goats, who'd gathered together and begun the contest, using their horns as weapons.

Cutting short his prayer, he cursed the devil, then went to pray in front of the most prominent rock in the Wadi Matkhandoush. This stood at the end of the wadi's western slope, where it met the Wadi Aynesis to form a single valley, deep and wide, sweeping down northeast until it merged, at last, into the Great Abrahoh in Massak Mallat.

The mighty rock marked the end of a series of caves, standing there like a cornerstone. Through thousands of years it had faced the merciless sun, adorned with the most wondrous paintings ancient man had made anywhere in the Sahara. There was the giant priest depicted over the full height of the rock, hiding his face behind that mysterious mask. His hand touched the waddanii that stood there alongside him, its air both dignified and stubborn, its head raised, like the priest's, toward the far horizon where the sun rose to pour its rays each day on their faces.

Through thousands of years the mighty priest and the sacred waddan had kept those features, clear and deep, majestic and vivid, set in the heart of the solid rock. There the priest stood, taller and larger than man's natural figure, inclined a little toward the sacred waddan. That too surpassed a normal waddan in size.

When, as a young man, Asouf had crossed the desolate wadi herding his goats, he'd never dreamed these paintings were so important. Today they'd become a focus for Christian tourists, who came from the most distant countries to see them, crossing the desert in their special desert trucks to gaze at the stone, their mouths open in amazement before its enigmatic splendor and beauty. Once he'd even seen a European woman kneel in front of the rock, murmuring indistinct words, and he'd known instinctively the words were Christian prayers.

Similar paintings adorned mountain rocks and caverns in the other wadis, throughout the Massak Satfat. He'd discovered them when, as a child, he'd tire himself out chasing after his unruly herd and go into the caves to find refuge from the sun, seizing a few moments of rest and amusing himself by gazing at the colored figures: at hunters with long, strange faces pursuing a variety of animals, among which he recognized only the waddan and the gazelle and the wild ox. Painted on the rocks, too, were naked women with great breasts, huge indeed, out of all proportion to the size of their bodies. This had made him laugh, as he thought of the breasts getting in the women's way as they walked along! He'd leaned back and shrieked with laughter, the echo ringing strangely through the unknown caves.

Then, as he climbed the mountains behind the goats, he'd discovered still further paintings. He saw, painted on the rock walls, hideous faces like the faces of ghouls, and of ugly animals not found in the desert. How was it his mother had never told him about these, even in her fairy tales? His father had never mentioned them either, before he died in dreadful pursuit of that charmed waddan.

“They're the people who used to live in the caves,” his mother told him. “The first ancestors.”

“But,” he objected, “you said jinn lived in the caves.”

She gazed at him bemused, then smiled, rocking right and left as she shook the milk in her hands.

“Are our ancestors jinn?” he persisted.

She stifled a laugh, but he saw it in her eyes even so. He repeated his question, and this time she just snapped:

“Ask your father.”

And so he asked his father, who laughed outright.

“Perhaps they were from the jinn,” he said. “But from the good jinn. The jinn are like people. They're divided into two tribes: the tribe of good and the tribe of evil. We belong to the first tribe—to the jinn who chose good.”

“Is that why we don't have any close neighbors?”

“Yes, that's why. If you live near bad people, their evil will strike you. Anyone choosing the good has to flee from people, to make sure no evil comes to him. That's what this group of jinn did. They lived in caves, from time immemorial, away from evil. Can't you hear them talking together, on moonlit nights?”

His mother broke in.

“Why are you frightening him,” she said, “with all this stuff about the jinn talking at night? Why don't you go and milk the camel instead, so I can have some milk before supper?”

Laughing again, his father went off. Asouf turned to his mother.

“I hear the jinn in the caves every day,” he said. “Talking to one another. They say the strangest things, and they even start singing sometimes. I'm not afraid of the jinn.”

She laughed and threw some pieces of wood on the fire.

Asouf still took pleasure in the jinn faces in the mountain caves. Fleeing the scorching heat, he'd take refuge, panting, among the hollows of the rocks. There he'd lie for a time, then crawl to the rocky wall and start taking off the layers of dust, until the lines painted in the rocks would begin to appear. Still he'd go on, wiping away at the mighty walls, until at last the faces would appear, masked or long, or else animals fleeing from the arrows of the masked hunters: waddan, gazelles, oxen and many others, huge in size, with long legs he never saw in the desert today.

In time he began calling the wadis and chasms and mountains by the names of the figures painted on their rocks. This was the Wadi of Gazelles, that the Path of the Hunters, that the Waddan Mountain, that, again, the Herdsmen's Plain; until, finally, he'd discovered the great jinni, the masked giant rising alongside his dignified waddan, his face turned toward the qibla,iii awaiting sunrise and praising Almighty God in everlasting prayer.

He was chasing the most unruly goats in the herd, who'd strayed from the rest, down the desolate Wadi Matkhandoush. He caught up with them, finally, at the place where the wadi merged with the nearby Aynesis, to form one deep, stately river valley, winding its difficult way across the barren desert, veering toward the Abrahoh plain. There a cluster of caves stood, crowned by mighty rocks; and these were flanked by that one towering rock that stood like a building soaring toward the sky, like a pagan statue fashioned by the gods. The masked jinni, with his sacred waddan, covered the colossal stone face from top to bottom. He stood long gazing at the tableau, then tried, vainly, to climb the rocks to touch the great jinni's mask.

There were boulders strewn around the rock face. He tried to gain a hold on the smooth rocks, but some stones gave way under his feet, and he fell on his back into the wadi.

He struggled on for a while, writhing with pain, then crawled on all fours to try and find some shade beneath a tall, green palm tree standing in the middle of the wadi. His heart was beating violently, the sweat trickling from his body. When he reached the tree, the shade had vanished. This surprised him. But he stretched out under the tree even so, waiting for the cruelly beating sun to set.

Next day, he found that the unruly goat, who had wandered from the herd and led him to the cave of the master jinni, had been snatched by a wolf that same night; and he remembered how the palm tree had abandoned him, stealing its shade away, when he'd taken refuge there after falling from the rock.