Читать книгу Blue Sunday - Irma Venter - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеThursday, 8 February, 20:26

It’s an Apple iPhone, no doubt password or fingerprint protected. After more than six weeks in the gutter it’s dead as a doornail. It’s pure luck that it lodged diagonally in the downpipe. I had to fetch Lafras’s braai tongs to get it out.

Maybe Willem lost the phone when he slipped out on Christmas Eve or when he fled. The rubber cover – black and angular – suggests that it might be a man’s. I can’t imagine how else it could have landed in the gutter.

But the bad luck is as big as the good luck. Did it have to be a bloody iPhone? It’s going to be almost impossible to unlock. Apple isn’t interested in working with the police, not even when it comes to terrorists wanting to blow up the USA.

Maybe Farr can find someone who can help, but I doubt it. And even if they do help, the courts will reject it as evidence.

I don’t even want to think about the recent storms. How many times has the phone been soaked through in the past six weeks? Three times? Six times? If I’m really lucky, there’s a backup of the phone in the cloud – which someone will also have to break open for me.

Wasn’t it the Israelis who recently helped the FBI to unlock that iPhone 5? The one that belonged to the terrorist?

I walk inside and put the phone in a plastic bag for Farr. Look at my watch. Half past eight. Tomorrow I have a whole lot of interviews, including one with Annabel Kirkpatrick.

Is there anything urgent I need to go and do at home? Eat? Nah. And Mrs Darling will feed Noah – there must be three tins of cat food left in her cupboard.

I walk to Katerien’s study, switch on the CD player and sit down in her armchair. I don’t know the music. It’s a rousing choir, men sounding like they’re marching off to make war.

The woman remains a bit of a mystery to me. I pick the book up off the chair’s armrest. A World History of Carpets and Tapestries. Right at the back is a shopping list written on the back of a Pick n Pay slip.

Pick n Pay, not Woolies or some or other organic market where the rich usually buy their groceries.

Bread, fish, potatoes and milk. “Thanks, Willem!” it says at the bottom of the list.

Katerien probably wanted to send him to the shop. The handwriting is hers – it’s the same as the notes in the diary on her desk.

It’s strange, this list, stranger than the paper Katerien used to write it on. Bread is right at the top of the till slip: In-store brown R7,95.

Who knows exactly how much a loaf of bread costs? What woman, living in a house like this one, knows the price of a loaf down to the cent? That’s not something you suddenly learn when your husband’s debts pile up. Knowing the price of bread – that’s linked to your childhood.

The price of all the items Willem had to buy is neatly totalled, with R190,25 circled as the total.

Why would she do that? Doesn’t she trust Willem, or is it just their financial position gnawing at her? Or is this just who she is? A down-to-the-cent person?

Lafras’s money matters were desperate and Katerien couldn’t help. She didn’t work. Her life was far more interesting than the average office routine, and her hobby – freediving – was pricey.

According to Sydney’s notes, Lafras had a mountain of personal debt, with very little money coming in. Over and above the services he suspended, like private security, he was struggling to pay the home loan and car instalments every month. His e-mails promise his creditors that a business transaction at the end of May would change everything. He pleads with the banks to be patient with him.

The only payments that are up to date are the children’s studies, pocket money and hobbies. School. University, rugby and ballet. Which makes me suspect that the kids didn’t know about Lafras’s money predicament.

Katerien even stopped diving.

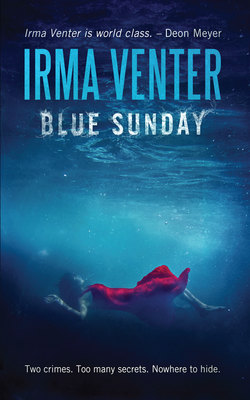

She and Lafras travelled to Ibiza six years ago where, quite incidentally, they watched the freediving world championship. She fell in love with the sport at the ripe old age of 42. It was something for which she had a completely natural talent – Annabel says she’d always had a fearless love of water.

By the time she disappeared, she could hold her breath for up to eight minutes and dive to a depth of eighty metres, without equipment.

Freediving is so unknown in South Africa that no one in the media really took notice. For the newspapers, it is an absurdity presenting itself as an odd fact in an even odder crime story.

I walk to the furthest cupboard in the study and open it. A freediver doesn’t need much equipment: swimming costume, diving goggles and fins. It’s the travel and practice sessions that are expensive.

How does it feel to dive so deep? Into the sea and the salt?

Eighty metres is deep. Twenty-four storeys deep.

I walk to the window. The swimming pool’s restless surface breaks the light of the house next door into shards of yellow. The water heaves and drops as though someone’s just dived in.

I look at the dense greenery and measure the distance to the ground. Did Katerien and Cath perhaps jump off from here when they heard Lafras shouting downstairs?

Probably not. The plants don’t look damaged.

The water’s drawing me.

I walk down the steps and out the front door. It’s quiet outside, the thick grass still wet from the afternoon’s rain.

I take off my shoes and sit on the edge of the pool. I stare at the dark surface. What draws someone to deep, deep water? To slip in there alone, your breath your enemy? The air that eventually wants to climb out of your lungs like a raging, mad animal, and all you want to do is open your mouth and …

I paddle my hand in the lukewarm wetness, drip water onto my trousers. I get up, take my clothes off and slip into the water.

I can hold my breath for 86 seconds.

At first there’s peace. Absolute, weightless, blue-grey peace.

Then the fear sets in. My hands start digging upwards through the water in raw panic, breaking through the surface, the night air sweet and fresh and perfect.

I lie at the edge of the pool, panting. Cough until the chlorine pushes up in my nose.

I know what kind of people dive this deep. You have to be fearless. In control. You can’t be afraid of the silence the water brings, of the rushing of blood in your ears. Of the beating of your heart that gets harder and faster, until it deafens your logic and you open your mouth, desperate for air.

Katerien van Zyl must be the calmest person in the world. And oh so in control.

I sit outside until I’m almost dry. I don’t want Farr to crap on me for walking through her crime scene with wet feet. I put the iPod’s earphones in and find Depeche Mode.

Nothing is better than eighties music. The lyrics still make sense, say something meaningful. “Words like violence break the silence, come crashing in, into my little world.” I sing along.

I go back into the house. It’s already eleven o’clock …

I go upstairs to Cath’s room, shift the curtains aside and wait for the security patrol to walk by at twenty past eleven. Two men with torches, alert and ready, looking for strangers in dark corners.

Familiar corners.

I can see at least two places they fail to look. Two shrubs that, perhaps a year ago, were knee-high, but now provide plenty of cover.

You get used to things – that’s the problem. You don’t adjust your thinking as the world slowly changes around you.

I sit on the snow-white bed.

I take a deep breath and scream as loudly as I can.