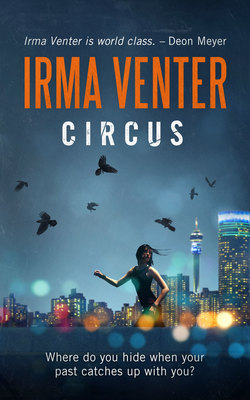

Читать книгу Circus - Irma Venter - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеJohannesburg, August 1989

I lie in bed, listening to the footsteps in the passage, slow and careful not to disturb anyone.

My bedroom door opens. It’s the Dutchman. He came back from Germany yesterday, irritable and exhausted. Something’s not right, but I don’t know what. His shoulders are stiff and tense.

I keep my breathing steady, pretend to be asleep.

The door closes.

The green dials of my alarm clock say it’s twelve-thirty am.

I wait. Hear the back door open. Click shut.

I get up. I studied until eleven, but sleep won’t come. I’m worried. Too many things are changing. And what’s supposed to change stays exactly the same.

Jonas hasn’t worked out at the gym for weeks. Daisy thinks the cops might have nabbed him again, but when Oom Tiny tried to find out, they just shrugged and said they had no information. And Peet is dead and Sandra’s little girl is due shortly. Peet’s dad is drinking as if he’s set on killing himself. His brothers are spewing venom. They talk about joining the right-wing AWB, about fighting to the bitter end.

The country is burning. I hear it everywhere I go. Only the TV and the Afrikaans newspapers make it sound as if everything is under control.

Somebody is lying.

All I want to do is go to varsity. Graduate and get away from here. The Dutchman can look after my mom. It’s his turn, after all, isn’t it?

I pray he won’t drop me now and do something stupid.

I put on my slippers, carefully open my bedroom door and walk down the passage to the kitchen, then out through the back door. I sneak over the cold grass to the garage.

Light shows under the door. Inside it’s quiet.

At least he doesn’t have another woman in there.

I open the door.

I startle the Dutchman. He sweeps piles of paper – money? – from the workbench into a blue toolbox and slams it shut.

“Adriana! What are you doing here?” He looks at his watch. “Can’t you sleep?”

I stare at the toolbox. “No.”

He gets to his feet, putting himself between me and the box. “Shall I make tea?”

I point at the box. “What are you hiding? What’s all that money?”

“It’s nothing.”

“Rubbish.”

He laughs, surprised by my anger. “It belongs to the Education Trust.”

“All that money?”

“Of course.”

“I don’t believe you.”

His smile vanishes. “I wouldn’t lie to you.”

“Says who?”

“Dammit, Adriana. Let it go!”

I fold my arms. No way am I going to do that. Something is going on. Something is bubbling and simmering, threatening to boil over.

He takes a step closer, squeezes my arm. “Sorry. I didn’t mean to be so curt.”

I shake my head. “Don’t be sorry, show me.”

“The money belongs to the Trust, I’ve told you.”

“Then it won’t matter if you show me.”

He thinks for a moment, then opens the box. My eyes skim over the foreign money. Piles and piles of notes. Used notes.

“What’s going on with your work? You spend your nights in the garage. Something’s not right.”

“Why would you think that?”

“Because it’s the truth. And I’m not stupid. Something is eating you.”

“I’m the director of the Trust. Obviously I’m going to be worried now and again.”

“About what? This money?”

It feels as if it doesn’t belong here.

“I brought it back from Germany. These are all donations for the Trust.”

“Who donates this much money to children they don’t even know?”

“Rich Europeans who oppose apartheid and want to give financial aid to poor black scholars and students. Come, you must get to bed.”

“Can you bring all that money into the country just like that?”

“Adriana, there’s no need to upset yourself. Come now.”

Something in his voice makes me wonder. He may not be lying, but he is not being honest either.

He gives me a long look. Smiles a little. “You don’t say much, but your eyes don’t miss a thing, do they? Ever since you were born.”

“Why don’t I know about this money you brought from overseas? Is it the first time? Does Ma know?”

“You know now. And your ma would be very upset. She … she has her own problems.”

He closes the box. Rests his hand on the blue lid. “I’m thinking of finding another job. One where I won’t have to travel so much. Maybe I could lecture again. Someone in Johannesburg is bound to have a job for an old physics professor.”

“But you’ve been with the Trust so long.”

“Things aren’t the same any more.”

“Why not? What has changed?”

He raises his eyebrows. “All these questions. You know I don’t talk about the Trust. With good reason. Not everyone is in favour of my work. The less you know, the better.”

I nod. I’ve known it since I was a child. And I’ve always heeded his warnings about not saying a word about the Trust. But something about this money scares me.

He puts his arm around my shoulders. “Let’s go make some tea. How are the studies coming along?”

“You know I hate school.”

“Just hang in there. A few more months, and you’ll be a student at Wits.”

He stops at the door. “The box … Don’t tell your ma or anyone else about it. It’s important.”

I relent. “I won’t. Promise.”