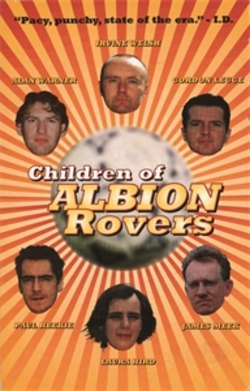

Читать книгу Children of Albion Rovers - Irvine Welsh - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Pop Life

ОглавлениеGORDON LEGGE

IT ALL STEMMED from their problems. With Martin it was money, with Ray it was women and with Hilly it was … well, it was always a wee bit more complicated with Hilly.

See Hilly was the sort of bloke that would take offence; and that was about the size of it. All that was needed was for somebody to say something, something commonplace, something you’d hear any day of the week, and next thing Hilly would be heading for the door, slating the others for being nothing so much as ‘spoilt bastards’.

That was what had gone wrong the last time, the last time the three of them had got together.

They’d been round at Ray’s one night when Martin, as he always did, started going on about his latest financial crisis. In the course of this, Martin had happened to come away with the one about how the more you earn, the more you spend. Hilly made a joke of it at first. The joke being that if Martin had a million pounds in his pocket, then chances were the million pounds would disappear before Martin reached the end of whichever street it was Martin happened to be walking on – with nothing to show for it, no recollection of what he’d done with it. But then Ray went and made the mistake of agreeing with Martin, saying that once you reached a certain level of income you never seemed to be noticeably that much better off. That was enough for Hilly. He did his ‘spoilt bastards’ routine and stormed off.

It was a good six months before Hilly had anything more to do with either of the other two. Six months in which Hilly was seen to hang around with the Kelsey’s or the Kerr’s, usually pissed or stoned, always laughing his head off.

Hilly was like that. When he was in a bad mood, he went out, he became more visible.

Ray, on the other hand, was the exact opposite, when Ray was in a bad mood, he kept himself to himself.

For years Ray had put up with the others going on about their successes and their conquests as far as women were concerned. Every so often all this would get to Ray; and, every so often, it would be Ray’s turn to slip out of the scheme of things.

Because he never really knew what he wanted from them, Ray was hopeless with women. Honestly, it was like watching a body trying to eat who didn’t realize the food was supposed to enter via the mouth. Hilly and Martin told him as much. There was even a time when they figured it was as well to tell the truth as anything: and told Ray that no woman they knew actually liked him. But before they’d had the chance to develop that, to talk it through to an extent that may actually have been of some kind of benefit, Ray made his excuses and left. He never blew up or anything, that wasn’t his style, he just, as Hilly put it, turned out the lights. Subsequently, the only times you’d ever catch sight of Ray were out late at night, out jogging, weights strapped to his wrists and ankles.

Back when they were younger, Martin had been the first to leave school. At a time when everybody they knew was signing on, Martin was changing jobs at the rate of one a month: dishwasher, labourer, that kind of thing. Even so, Martin was always short of money, always asking for loans. To his credit, he did pay back; but he was never the one to turn up at your doorstep and say, ‘Here’s that money I owe you.’ No, Martin had to be hunted down, and you had to embarrass yourself by asking for what you were rightfully owed. Likewise, it wasn’t unusual to be out with Martin, and for some complete stranger to come over and demand money from him. Such instances rattled Ray and Hilly. Consequently, Martin would get slagged to bits, be made to feel really rotten, to such an extent that it would prompt Martin’s hiatus. Martin, though, didn’t storm off like Hilly, or turn in on himself like Ray. No, what Martin did was to run away. Martin fucked off. He would somehow manage to borrow twenty quid off somebody or other, then disappear off to the city, or away down south, or, on two notable occasions, over to the continent.

But it wasn’t just the borrowing Martin did: Martin sold things. One time that was really annoying was when Martin sold his Bowie collection. He hadn’t even sold it to a collector, just some dud at a record fair for about a tenth of what it was worth. All he’d got in return had amounted to little more than a good night out. But that wasn’t the point, the money wasn’t the point, the point was you didn’t sell your records.

For it was records that had brought them together in the first place. At school, they’d noticed the same names scrawled on each other’s bags, books and desks. From there they’d got to talking. Soon, they were exchanging records and making up tapes for each other. It wasn’t long before the three new friends were spending all their free time sat in front of each other’s speakers, appraising their own collections, investigating their brothers’ and sisters’; talking about nothing other than records.

Whilst everybody else of their generation seemed content to spend Saturday mornings hanging round up the town, giving it the best bored teenager routine, Martin, Ray and Hilly treated Saturday mornings as though they were on a no-frills, top-secret assignment. They’d head up the town, straight to the record shop, browse for exactly twenty minutes, make their purchases, then head straight back home.

It was a truly amazing time; discovering all this great music, getting overwhelmed by it. And the great thing was it wasn’t a case of one liking this, the other liking that – what one thought the others were thinking, what one said the others agreed with. In as much as they ever could be the same, they were the same: they dressed the same; they did the same things; they were all in the same boat as regards money, women and opinions.

Then, just as they were getting their interviews with the careers advisory woman, punk rock happened.

Initially, it was great. More great records. Records, in fact, that were even better than a lot of the stuff they’d been listening to. It was a discovery again. Only this time round, it was a discovery they could call their own. This time, they weren’t out hunting for records; this time, they were waiting for records.

Yet while Martin, Ray and Hilly were equally keen to embrace the new, they responded to it in completely different ways. For Martin it meant party, it meant always going out, having to try everything: every drug; every fashion; every possibility. Performance was what attracted Ray, being on stage – the forlorn hope being that women were only just waiting to fling themselves at the feet of the local axe-hero. For Hilly it became as important to state what he didn’t like as much as to state what he did like. So while Martin would be all excited, looking for a party, looking for the action, going, ‘What’s happening? What’s happening?’ Ray would be thinking about his band, and, being a bit unsure, would waffle on something about, ‘Don’t know. Supposed to maybe be a gig in a couple of months. All depends, though …’ Hilly, on the other hand, God bless him, was never too bothered with having to think about things. Hilly just started every second sentence with the then trademark words, the italicized ‘I hate …’

And there you had it, the three friends: the hedonist, the hopeful and the hostile. Whenever Ray landed a gig the situation would transpire that Martin wouldn’t turn up because he hadn’t the money, while Hilly wouldn’t turn up cause he thought the band were crap.

Responses that not surprisingly got right royally on Ray’s nerves.

Not that Ray was ever the one to talk, mind, not when it came to getting on folks’ nerves, anyway.

Thing was, Ray would always be leeching around in the hope of meeting up with women. He spent a small fortune treating Martin, going to this pub, that club, chasing parties here, heading round there. Not that it ever achieved the desired purpose. Martin was so restless, such a party animal, that by the time they got served somewhere, or got accepted somewhere, Martin would be on about where they would be going next, where they could be going that was better. Come the early hours of the morning, when everyone else was heading home, Martin and Ray would still be stopping off at the cash machines, stocking up for that elusive good time.

Ray was also into pestering Hilly to go out. A mission which was as doomed as any mission ever could be. See Hilly was never much of a mixer. Hilly’s idea of a good night out was to sit in the same seats of the same pub with the same faces he always sat with, talking about the same things he always talked about. When Hilly was in company he didn’t care for, he said so; when Hilly was in a place he didn’t care for, he left.

Over the years things went on like this. The three friends got on with their lives but, increasingly, struggled to get on with each other. Martin married a rich man’s daughter, Hilly married a lassie who lived three doors away, Ray never married. Ray could, however, lay claim to being the most well off, seeing as how he became an administrator for the region’s education services. Martin worked for the health board in a self-advocacy project while Hilly earned his crust with a family-run removal firm.

Despite the changes that entered their lives, and the fact that, by this time, they were hardly ever seeing anything of one another, Martin, Ray and Hilly continued to share a bond that came from them spending so much time together when they were growing up. When two of them bumped into each other, they invariably spent most of their time talking about the third – often to the exclusion of even talking about themselves.

On those rare occasions when the three did get together, it was only a matter of time before they broached the subjects they never liked to talk about, only a matter of time before one of them upped and opted for the early bath.

Even though the others were never in the slightest bit interested, Martin would always contrive to go on about his money problems. He didn’t get much sympathy. The fact that Martin never had anything to show for all this money that mysteriously disappeared was too much for Hilly. The fact that Martin admitted to nicking money from his wife, and denying money to his wife, was enough to send Ray off.

Ray was by far and away the wealthiest of the three. Ray knew this, and didn’t like it one little bit. The others never intended it as such, but whenever Martin went on about the ease with which Ray accumulated his wealth, or when Hilly went on about what he saw as the pointless possessions Ray had a habit of acquiring for himself, Ray felt they might as well have been having a go at his failure with women – he was rich because he was alone.

But while Martin and Ray at least admitted to having problems, Hilly never would. There was nothing wrong with Hilly. If folk couldn’t handle a few home truths then that was their problem. These self-styled ‘home-truths’ covered everything from the mildly embarrassing right through to the downright ignorant. The mildly embarrassing was when Hilly was in the home of somebody he considered middle class. In such circumstances, Hilly would always make a point of pilfering something, usually from the drinks cabinet, occasionally from the bathroom, but always something expensive, always something that would be missed. The downright ignorant side of Hilly showed with his penchant for having a go at Martin and Ray, and folk close to Martin and Ray. Hilly was a bit of a wind-up merchant, where nothing was ever practical, everything was a matter of principle. As long as Hilly was having a good time he wasn’t the one to care. Martin and Ray couldn’t stand it. It would always end up that one of the three would up and leave.

Then, following the ‘the more you earn, the more you spend’ incident, two whole years passed without the three of them being together. They only ever saw each other in the passing, down the town or going to the games. As for getting together, arranging something; well, they didn’t really see the point. It was as though they’d gone through a bitter divorce; they associated each other with their problems and that was that. The memories just seemed to be bad memories.

As time wore on, though, it was the normally self-assured Hilly who came to realise just how much he missed the other two. Hilly had no fervour for socialising or meeting new folk. Hilly had such a dislike of most folk, anyway, that it was pointless him even contemplating going out and finding new mates. Sure, he got on with the folk at his work and with his family but somehow, something, was missing.

And Hilly knew what it was. His two friends. Martin and Ray. Hilly wanted to see them again. Properly. He wanted the three of them all to get on with each other.

Hilly thought about it, about how they were all doing away fine on their own but how they couldn’t get on when they were together. It was then Hilly had an idea, the same idea he always had. When things weren’t working out, then you went back to the way things were when they did work out.

Hilly contacted Martin and Ray. He told them how they should all meet round at Ray’s on the first Tuesday of the following month. The idea being that they would only talk about records. Seeing as how that was what had brought them together in their youth, there was no reason why it shouldn’t continue to be the case. They would bring along their new purchases, play them and talk about them. On no account were they to talk about anything other than records.

In love with the romance of the idea as much as anything, Martin and Ray said yeah, they were willing to give it a go.

And that’s what they did.

Unfortunately, though, the first occasion proved to be little short of a disaster. True to form, Martin hadn’t brought anything. He said he hadn’t had the money. Ray, meanwhile, had brought damn near everything. He’d even brought along stuff he hadn’t yet played. Hilly was furious with him. After about two-and-a-half seconds of each record, Hilly would go on about how crap it was, slagging it to bits, and slagging Ray for having more money than sense. Hilly himself was the star of the show, playing his records and enthusing about them.

The next time round was better. Throughout the month Martin had stayed in, listened to all the decent radio programmes, latched onto something that was brilliant and bought it. Ray and Hilly agreed, it was a classic. Ray himself had spent his lunchtimes hanging round the record shops, listening to what the kids were wanting to hear, and buying the best. It was mostly dance but it had a power and urgency that won over the others. Hilly, as was his want, took his cue from what the papers were raving about. Yet even he had to concede that what Martin and Ray were playing was as good in its own way as the stuff he normally listened to.

And that set the precedent. Martin listening to the radio, Ray hanging round the record shops and Hilly reading his papers. They held their monthly meetings, and they never talked about anything other than records.

At first they’d been concerned that what they were bringing along was good enough, making sure there wasn’t some little reference that would draw the derision of the others. But, in time, they grew confident. They had a pride in what they were buying. Equally, they were keen to hear what the others were buying.

Before long, they began to notice changes in each other. Martin had started off by coming along with just a couple of singles, but now he was appearing with a few singles and a couple of LP’s. Not only that but people in the streets had been stopping Ray and Hilly to ask for Martin. Nobody was seeing much of Martin these days. They’d all assumed he’d gone a-wandering again. But no, Martin was around. Martin was doing fine. Simple truth was Martin wasn’t going out because Martin didn’t want to go out. He wanted to stay in and play records. Many’s the time he’d got himself ready to go out but he always had to hear just one more record, then another, then another. It ended up with Martin having to ask himself the question: what did he want to do, did he want to go out, or did he want to stay in and play records? So Martin stopped going out.

The change in Ray had to do with his appearance. Whereas Hilly had always dressed classically (501’s, white t-shirts) and Martin went in for the latest Next or Top Man high street fashions, Ray always looked as though he was going to a game in the middle of January. Now, following their Tuesday nights, Ray was taking a few chances, and it was paying off. He was looking alright. He was getting his hair cut every six weeks instead of every six months. His flat seemed different as well. It was more untidy, yet it was less filthy. It looked like he was living there rather than just staying there.

The big change, though, was with Hilly. Martin and Ray were always wary of Hilly, knowing that Hilly was perfectly capable of dismissing their purchases – and, by implication, themselves – with either a subtle shake of the head, or, by going to the other extreme, and bawling and screaming his socks off. But Martin and Ray were so into what they’d bought, so passionate about it, that they did something nobody else could ever be bothered to do: they argued with Hilly. Nobody ever argued with Hilly. Folk usually just ignored him, or laughed at him, nobody ever argued with him. But Martin and Ray did – and they won. They won him over. They got him to listen to what they were playing, and to listen to what they were saying.

On a couple of occasions they almost broke the rules. There was one time when Hilly was so excited he’d phoned Ray up at his work, telling him how he had to go out and buy something. Ray had said no, it had to keep, there were rules to be obeyed. Another time they’d all turned up with virtually the exact same records. Martin seemed uncomfortable. But he didn’t say anything. Next time round, Martin appeared with the same number of purchases as he’d had the previous month. He said that yes, the notion had entered his head just to turn up with a batch of blank tapes, but that he’d decided the important thing was to own the records. That was what it was like when they were younger, that was the way he wanted it now.

The three friends still argued, of course; but they only ever argued about records. They argued about what made a good record, whether something ephemeral could ever possibly be as good as something that was seminal. They argued about whether bad bands could make good records. They argued the case for Suspicious Minds being better than Heartbreak Hotel. They argued with passion, with loads of logic, even with blind prejudice – but they never held back, never kept their thoughts to themselves.

Hilly had long held the belief that the place for dance music was the dancefloor. Not that he was bigoted against it or anything, just that playing records that went beep-beep thwack-thwack in the privacy of your own home was about as pointless as playing 95% of live LP’s. But he came to understand, through force of sheer enjoyment as much as anything, that the records could stand on their own, that they were as valid and wonderful in their own way as the stuff he normally listened to.

As for Martin; well, it wasn’t so long since Martin had all but stopped buying records. Occasionally, he’d’ve got something from the bargain bins, but he wasn’t involved, he was purchasing out of a sense of obligation rather than want or need. Now he was buying things full price. Not only that but because he was taking his cue from the radio, he was ordering the likes of expensive imports and limited edition mail order. Martin’s disposable income was still short in terms of its lifetime, but now at least there was something worthwhile to show for it.

Likewise with Ray. Prior to the arrangement, Ray had been the one blanding out. When it came to music, what he’d been buying had been predictable – comfy compilations, bland best sellers. He’d even bought a CD player. But, after a few meetings, he’d gone back to vinyl. Like he said, he’d got the taste again, and owning vinyl was like tasting chocolate.

It was as if they’d gone back to the old days, back to their youth. But they knew the only way to get the most out of records was to hunt them down, to be obsessive. See that was the great thing about records: you never just went out and bought the best, you had to discover the best. As much as the powers that be had tried to market so-called ‘classics’, records weren’t mere things you owned, like accessories, and said, ‘I’ve got it,’ like you’d say you’d ‘seen’ a film or ‘read’ a book.

As agreed, the three friends continued to have nothing to do with each other other than the monthly nights round at Ray’s, and then they only ever talked about records – they never talked about themselves, they never gossiped, they never discussed what was happening in the news. Originally, this had meant that they wouldn’t be bringing up their problems, letting their personal lives interfere with their friendship. The strange thing now was that they were all doing fine. But they didn’t tell. Martin had bought a house, Ray was engaged to be married and Hilly had become a father. Most folk thought it was Hilly’s parenthood that had turned him into a more reasonable bloke, but Martin and Ray liked to believe it was the time they spent together, listening to their records and talking about them, that had brought on the change that meant, for the first time, Hilly actually appeared to be interested in folk when he was talking to them.

Over the festive season there was no exchange of presents or even cards, instead the three friends compiled lists of their records of the year, compared them, and analysed those that were in the papers and those featured on the radio. During the summer they timed their holidays so’s not to coincide with the first Tuesday of every month. There was no illness or problem that kept them from their appointments. They were never late, nobody ever left early.

The summer was always a lean time for new releases. In view of this, it was agreed to forego the norm and have an evening in which they brought along lists of their all-time favourites. Top two hundred singles, top hundred LP’s. For the whole month they never went out. Wanting to be as sure of their lists as they could, they stayed in and played and played and played.

It proved to be a great night. Easily the best yet. So many records they’d forgotten about. They’d had near-enough identical top fives but after that it was just classic after classic after classic. The lists were beyond dispute. It was almost scary that there were so many great records that they all knew off by heart, that they all knew so much about. Thinking about it, there had to be thousands. Those they’d listed had only been a fraction. The lists had been too limiting. Next time round – if there was to be a next time round, there was some debate as to that – they’d specialise. Not in terms of genre – that was crass – but in terms of period.

That night, they opened up, they shared their dreams. In turn, they fantasised about putting their knowledge into words or owning record shops; but, like when they were young, they only ever fantasised about it. Although they now had the talent and the financial clout to make it happen, they didn’t want to be involved. Partly this was because it would break the rules of their friendship, but mostly it was because they realised they were still what they’d always been – they were fans. It was for this reason that none of them – excepting Ray’s brief flirtation – had ever pursued the performing side: they didn’t want to be stars, they wanted to have stars. In the same way that, by and large, folk don’t want to be Gods, folk want to worship Gods.

And so things continued.

Until, that was, the evening one month short of the third anniversary of their first meeting.

Hilly didn’t turn up.

Hilly was never late. He’d never been late for anything in his life. He just didn’t do things like that.

Martin and Ray waited. They didn’t start. They wouldn’t start without Hilly.

After about an hour, the phone rang. It was a guy who introduced himself as being Phil, Hilly’s brother-in-law.

There’d been an accident, Phil said, Hilly had been involved in an accident up at his work.

It seemed important for Phil to take his time and explain as best he could everything that had happened.

It was ten days ago. Hilly had been doing a flitting over the old town. They’d been taking a chest-freezer down a flight of stairs when the guy at the top end had lost his grip. While the guy endeavoured to retrieve his grip, Hilly had tried to wedge the chest-freezer against the bannister. But, somehow, the chest-freezer slipped, pushing Hilly down the stairs.

Phil said he wasn’t sure what had happened after that, but next thing anybody knew was that Hilly was flat out at the foot of the stairs. He must’ve lost his footing or something because the chest-freezer hadn’t moved. It had stayed put, perfectly wedged between the bannister and the wall.

Ray asked if Hilly was alright.

Phil took a deep breath. No, he said, Hilly wasn’t alright. Hilly was in a coma. He’d been unconscious for ten days.

As much as Ray had been half-expecting something like that, the actual words still managed to shock him in a way that amounted to nothing less than physical pain.

Ray asked when they could go up and visit. Phil said whenever, they could come up any time they wanted.

Ray thanked Phil for letting them know, and said they’d probably be up later on.

Ray told Martin. They talked about what they should do.

They were both thinking along the same lines, but they didn’t want to do it – they didn’t want to make a tape up for Hilly.

It seemed corny. It seemed sick. It seemed like interfering.

But the more they went on about it, the more it made sense. Really, it was the only thing they could do. That was what this night was all about. The records were more important to Hilly than Martin and Ray ever were. Hilly was the one who always said he’d rather be blind than deaf. It was one of those challenges he always set the other two, like a childhood dare – would you rather be blind or deaf?

The deciding factor was when they got round to thinking about what would’ve happened if the circumstances had been reversed. It’s what Hilly would’ve done. Hilly wouldn’t even have thought about it, he’d just have gone ahead and done it.

Ray looked out the list of Hilly’s all-time favourite records. They used that as their guide to make the tape up.

It proved to be a truly horrible experience, listening to all these records, records that would normally have got them so excited, records, as Hilly put it, that made them feel so alive. After a while, they turned the sound as low as they could get away with, and busied themselves doing other things. Martin made a few calls, Ray went for petrol.

Even so, the process, by its very nature, could not be speeded up, and once they’d filled a side of a C-90, they called it a day, and headed up to the hospital.

They always said that the thing about folk in these situations was how normal they looked, how peaceful, but Hilly didn’t look normal. He didn’t look pained or distressed or harmed in any way, but in no way could you have said he looked normal.

There were four visitors already sitting round the bed.

Other than to say hello, Martin and Ray hadn’t spoken to Hilly’s mum for close on ten years, but she acknowledged them as though she’d only just seen them the day before. The passing of so much time didn’t seem to mean anything.

A bloke stood up and offered his hand. He introduced himself as being Phil, Hilly’s brother-in-law, the guy that had phoned. Phil introduced the two women sitting by the bedside as being his sisters, Sarah and Julie. A second later he added that Sarah was Hilly’s wife. Martin and Ray hadn’t seen Sarah since the day of the wedding. If they hadn’t been told her name, they wouldn’t’ve recognised her.

Phil started to apologise for taking so long to let them know, but stopped when Ray shook his head to indicate that it didn’t matter.

Martin took the tape and the Walkman from his bag. He asked if it was okay to leave them. The folk seemed a bit unsure but nobody objected. Martin explained as how the tape was made up of Hilly’s favourite records. Everybody looked at Martin as though he was talking some kind of foreign language.

Hilly’s mother told Martin just to go ahead. She put her arm around Sarah’s shoulder and said, ‘You know he loves his music, hen, you know he loves his music.’

Martin switched the machine on. The tinny beat could be heard coming through the earphones.

Ray went over and turned the volume up. It wasn’t loud enough. It wouldn’t’ve been loud enough for Hilly.

To look at it, it was like one of those awkward scenes folk always laugh at when they see it on telly. Hilly wouldn’t’ve laughed, of course. Hilly liked a laugh but Hilly hated comedy. He had never seen the point of jokes and if he’d ever laughed at a film or sit-com then there was nobody present when he’d done so. Knowing, he called it. Knowing meaning smart-arse, knowing meaning ironic. But, in practice, it always turned out to be the exact opposite. Folk that knew nothing about nothing pretending they did.

Soon, Martin and Ray were beginning to feel distinctly uncomfortable. Not for themselves but for Hilly’s family. They felt they didn’t belong. They didn’t know these people. The only person they knew was the one on the bed, and, at this precise moment in time, they felt as though they’d never really known him at all. They felt as though they’d only ever met him.

Martin took the initiative. He suggested that maybe they should come back later. Ray agreed. He took out a business card and handed it to Sarah, telling her that if ever she was needing any help with anything, anything at all, then just to get in touch. He said it again just to make sure she understood that he meant it.

Martin and Ray left the hospital. Without so much as a word, they drove out to the docks. They didn’t want to be indoors, in any kind of home.

It was no wonder that at times like this folk had a habit of turning religious. There were no rules telling them how to behave. No precedent that told them how they should feel. Everything they felt was wrong. Guilt. Regret. Shame. Fear.

And, most of all, anger.

They started flinging stones and rocks out into the water, burning off their energy. This was the worst night of their lives, and it was compounded by the near ridiculous image of Hilly’s family sitting round his bed watching him listening to a Walkman.

These people didn’t understand.

Or, then again, maybe it was Martin and Ray who didn’t understand.

See that was the problem. Their Tuesday nights were tantamount to a secret. And folk liked secrets. Its very success had to do not only with the way they avoided bringing up their problems, but the way it all had nothing to do with anybody else.

That was how no one had got in touch with them. Nobody knew about them. Nobody knew what went on. Hilly would never’ve mentioned these nights to anybody. Sure, okay, he probably said he was going round to see friends and play records, but he’d never’ve told anybody about what went on. Martin and Ray didn’t, and if they didn’t then there was no way Hilly would’ve. You could only talk to folk about such things, your passions, when they would understand, and nobody they knew, nobody Hilly would know, would understand all this.

For no real reason they could think of other than they wanted to, Martin and Ray decided to head back up to the hospital.

They’d leave it a while, though. They wanted privacy. They wanted their secrecy.

They went back to Ray’s and made up more tapes. They taped records from Hilly’s list, records from their own lists that Hilly had regretted not including in his own, and the records they’d intended playing that night. This time, they taped with the sound up. They were positive about what they were doing. They were doing what it made sense for them to do. The only thing they could do. It was what they’d done for the first Tuesday of every month for the past three years and it was what they were going to do now.

When they were ready, they returned to the hospital.

Sarah was still there, still sitting by Hilly’s bedside.

She explained as how one of them always stayed over and slept on a Parker Knoll in an adjoining room. She didn’t seem as wary as she’d done earlier. Truth be told, she looked too tired to be bothered. The Walkman lay on the bedside table, the earphones by its side.

Martin put the new tape in the machine. He fitted the earphones on Hilly, then switched it on.

It was Ray who broke the silence. There were things that needed to be explained.

‘You don’t know anything about us, do you?’ he said.

Sarah shook her head.

‘It’s a long story,’ said Martin.

And, since there was nothing else to do, they told her the story: about how they first met; how they always fell out; their nights playing records.

When they finished Ray laughed. ‘Do you realise,’ he said, ‘this is the first time we’ve ever talked about him and not slagged him off?’

The three looked over at Hilly. The music stopped. Ray switched the tape over. He turned the volume up a bit then closed the curtain round the bed.

Sarah told the story of how she met up with Hilly. It was a familiar story. The courtship was so typically Hilly, so single-minded, so matter-of-fact.

Just as Sarah was going on to explain what plans she and Hilly had been making for the future, the curtain round the bed was pulled back.

It was the doctor. ‘Do you think you could maybe turn that down, please?’ she said. ‘It carries, you know.’

Martin apologised. He explained what they were doing.

‘Still,’ said the doctor, ‘it’s past one o’clock in the morning.’

Martin went over. He turned down the music.

The doctor tickled Hilly’s toes then made a note on her clipboard. ‘Are you alright?’ she said to Sarah. ‘Do you not think that maybe you should get some rest?’

Sarah looked at the other two.

‘On you go,’ said Martin. ‘We’ll stay here.’

‘Are you sure?’ said Sarah.

Martin and Ray nodded. They weren’t going anywhere. The doctor smiled a thank you as she led Sarah away into a tiny side-room.

Alone at last, Martin and Ray looked at each other. Then at Hilly. They’d done all they could. They’d played his favourite records, they’d played the ones he’d regretted not having on his list, and they’d played the ones they’d intended playing that night. It was pathetic. Here they were, grown men, successful men, yet this was all they could think to do. Because of Hilly they’d changed so much, so much for the better, but now, when it was most needed, there was nothing they could do in return.

Martin took a piece of paper from his pocket. It was the list of Hilly’s favourite records.

Martin studied it. He wasn’t staring at it, he was studying it.

If there was an answer, if there was something that could be done, then this was where they’d find it.

After about five minutes Martin reached over and switched off the Walkman. He removed the earphones and placed them and the machine on the bedside cabinet.

Martin continued to study the piece of paper. A further five minutes passed before he finally spoke.

‘I think you’re wrong,’ he said. ‘I think you’re wrong. And I’ll tell you why I think you’re wrong. No, listen, listen, you’ve had your say. See …’

Martin went through the list, talking about what they always talked about, the records. Ray pushed up his sleeves and joined in.

They talked about nothing other than records, slagging off the things they always slagged off, going on about the things they always went on about, how important it all was to them. This was what it was normally like. Tuesday nights, the three of them together, talking, talking only about records.

Before anybody knew it, it was four o’clock in the morning. They’d been going on like this for the best part of three hours when the doctor returned with another doctor. It was the change of shift, the handover.

The doctor tickled Hilly’s toes.

She tickled Hilly’s toes again.

She leaned over and shook Hilly by the shoulder. Gently at first, then quite vigorously.

‘Can you hear me?’ she said.

Hilly moved his lips. He didn’t say anything but he moved his lips.

Martin went through and got Sarah. By the time they returned Hilly seemed less peaceful, more restless, almost groggy. For the first time, he looked to be genuinely ill and everybody seemed pleased.

Within the half hour, Hilly was sitting up, taking some fluids and responding to the doctor’s questions. He was a bit doped and sluggish but, other than that, there didn’t seem to be anything much wrong with him.

Hilly took it all in. Yes, he knew who he was. Yes, he remembered what had happened. Yes, he understood that he was in hospital.

In fact, waking up in hospital didn’t seem to bother Hilly – whereas the sight of Martin and Ray did. ‘I just had this crazy dream about you pair,’ he said. ‘Going on and on. Havering the biggest pile of nonsense I’ve ever heard.’

Martin and Ray smiled, but it was Sarah who laughed. ‘Then you could maybe introduce us all some time,’ she said.

Hilly turned his head away. The very thought seemed to cause him nothing but shame.

It was then that he noticed the Walkman.

Hilly reached over. He picked up the tapes and the piece of paper.

‘Your favourite records,’ said Ray.

‘We taped them for you,’ said Martin.

Hilly seemed chuffed. ‘So this is what brought me round then, eh?’

Martin and Ray nodded. Although, as they did so, they were thinking to themselves as how it wasn’t the tapes, the music, that had brought Hilly round – no, if anything was responsible, it was them, the sound of their voices. Not that they’d ever dare dream of telling Hilly that, of course. After all, the three friends had an arrangement to keep: they’d only ever meet up on the first Tuesday of the month, and they’d only ever talk about records.