Читать книгу The Day of Creation - J. G. Ballard, John Lanchester, Robert MacFarlane - Страница 7

1

Оглавление‘Dreams of rivers, like scenes from a forgotten film, drift through the night, in passage between memory and desire.’

Or, better, let’s set it like a poem:

Dreams of rivers,

like scenes from a forgotten film,

drift through the night,

in passage between memory and desire.

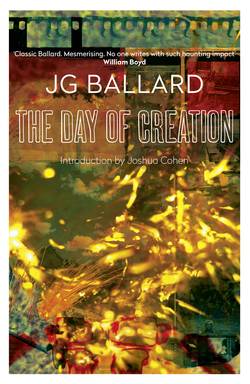

Now it reads less like a first sentence – which it is, the first sentence of J. G. Ballard’s The Day of Creation – and more like the novel’s displaced epigraph.

Now we can begin, and I’ll gush about this and leak about that and then this introduction will trickle to an end and you’ll begin the novel proper only to find that sentence again and perhaps you’ll feel – perhaps you’ll feel now that I’m exhorting you to – the prosodic ebbs and flows of water. The opening sentence of Finnegans Wake is the continuation, the circumfluence, of its closing sentence. Joyce’s first page begins: ‘riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.’ His last page ends: ‘A way a lone a last a loved a long the’

No capitalization at top, no punctuation at bottom.

Of course, Joyce also wrote poetry and his prose was ‘poetic’ – whereas we read Ballard for a pitilessly mass-produced language more suitable to ‘the contemporary’. Or we assume we do (or we assume pitiless mass-production is more suitable), because the stark sad thingness of drainage culverts and overpasses and parking lots and empty swimming pools – empty except for the junkfood wrappers and condoms and cigpacks and bottles – too often overwhelms the ambient mosquito music abounding.

Prose lets us see and poetry lets us hear but the best of both do both at once, though so does 3D IMAX with Dolby Digital.

So, ‘like scenes from a forgotten film’ – what does Ballard mean? Who forgot this film and why? Rather, is this line disposable? Or is a brackish meaning bubbling behind it? In film, by which I mean mostly in Hollywood, when everything’s been shot and edited and even reshot and re-edited and test audiences still can’t understand what the hell’s going on, directors or, frequently, producers in conflicts with their directors, seek to salvage the thing either by introducing voice-over – from the hero, perhaps, or an omniscient God-narrator, explaining, ‘An hour before dawn, while I slept in the trailer beside the drained lake, I was woken by the sounds of an immense waterway’ – or by slapping together a title card that proclaims: ‘Africa, The Present.’

‘Like scenes from a forgotten film’ strikes me as Ballard’s equivalent of this technique. The line introduces a first-person narrator (first-person is literature’s overdubbing), while it also serves to reorient – or deoccident – you, the reader, for whom film, or TV – the screen – has become so primary a medium as to be beyond second nature: The mediation has become Nature Itself.

After that line Chapter 1 continues its cinematic panning:

As on all weekend visits to the abandoned town, I was seized by the vision of a third Nile whose warm tributaries covered the entire Sahara. Drawn by my mind, it flowed south across the borders of Chad and the Sudan, running its contraband waters through the dry river-bed beside the disused airfield.

But everything’s so vivid that you’d be forgiven for not having noticed that the theatre you’re in is still just a skull: one man ‘seized by the vision’, a Nile ‘drawn by my mind’. It’s as if we have to be ensconced in an imitative darkness before that line about film is granted its literal justification, in the midst of the chapter: refugees from the Sudan are feeding campfires with wood stripped from a police boat, using ‘strips of celluloid left behind by the film company’ as accelerant.