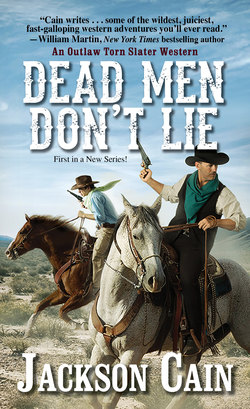

Читать книгу Dead Men Don't Lie - Jackson Cain - Страница 31

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 19

Their train was in a waterless waste in the middle of nowhere when Eléna heard the whistle blow and the train slow. Not a good sign. She shouted at Antonio:

“Go see what’s happening.”

Climbing the nailed-on ladder, he mounted the adjacent boxcar and jogged along the boxcar roofs to the tender, which was piled high with kindling, to the locomotive. Just around the bend, he could see a big lightning-smitten cottonwood tree lying laterally across the tracks. Its thick, massive trunk branched out into a dozen large dense limbs heavy with countless branches.

The engineer and fireman looked up at him. They both wore gray canvas pants and dark cotton shirts. Their hair was black, their skin and clothes were stained by smoke and soot.

“Does that trunk look like lightning hit it to you?” the engineer, a big man named Carlos, asked.

“You could bore a hole in the tree,” Antonio said, “fill it with blasting powder, and blow the trunk in two. We’d do that in the army when we were too lazy to chop the trees down. You’d achieve the same look.”

“I don’t like it,” the engineer said. “It’s too big a coincidence.”

“And I don’t see signs we had a lightning storm here either.”

“We still got to move that hideputa [son-of-a-whore] log,” Fernando, the fireman, said, “whether we like it or not.”

“You gonna help?” the engineer said. “You’re big enough to move the tree yourself.”

“I got two women to look after, one of them hurt and sick. Anyway, you got a bunch of soldados on the train. They need to come out of their boxcars también—in case we are attacked while we’re moving that tree.”

“That’s why they’re here, ¿verdad?” the engineer said.

Eight rurales soldados were already climbing out of the boxcar nearest to Antonio’s flatcar and were walking down the track toward the fallen tree. They wore gray uniforms, sombreros with broad brims and high crowns with four side-creases, and brown horseman’s boots. They all had big black mustaches and had sidearms strapped to their hips. Canvas bandoliers filled with shiny brass cartridges crisscrossed their chests. Several of them carried slung rifles from their shoulders.

“I didn’t think those soldados would leave that bullion safe alone in the boxcar,” Fernando, the fireman, said.

“I thought they’d stay in it forever,” Carlos said.

Madre de Dios, we’re on a bullion train, Antonio suddenly realized.

“Them lazy bastardos’d rather have you removing that cottonwood for them,” the engineer said.

“I have to get back to the two women,” Antonio said.

“Well, that log ain’t movin’ itself,” the fireman shouted to the soldados.

“Have them scout the nearby arroyos también before they start moving that tree,” Antonio said. “Banditos could be hiding nearby—maybe in an arroyo or behind those rocks. They’ll be sitting ducks once they get it off the ground.”

Antonio pointed to a cluster of large boulders on a ridge overlooking the fallen cottonwood.

“How do you know that?” Fernando asked.

“Scouted several years in the Mexican army.”

“Why did you quit?” the engineer asked.

“A bullet through the knee.”

“I wouldn’t mind trying something different, amigo,” Fernando said. “Is the army all right? You like it before you got shot, I mean?”

“It’s okay if you’re loco-estúpido.”

“Speaking of soldados,” Carlos said, “they’re up by the tree.”

“We better help them,” Fernando said.

“Have them scout that terrain first,” Antonio repeated.

“We’ll be lucky if we can get them to move the tree,” Carlos said.

By that time, Antonio was jogging along the boxcar roofs, heading back toward Eléna and Rachel.

He didn’t like this stop at all.