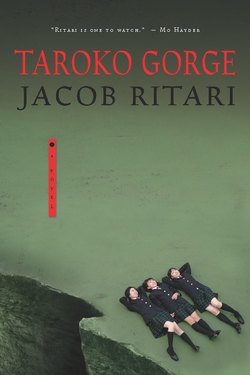

Читать книгу Taroko Gorge - Jacob Ritari - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PETER NEILS

ОглавлениеI was fourteen when I stopped believing in God. At the time it wasn’t dramatic. I remember lying in the bedroom of that old, drafty house and thinking: If you are there, I hope you’ll forgive me if I stop believing in you for a while, because right now I just don’t see the reason. When you’re fourteen, you don’t have much reason to believe one way or the other. Everyone tells you what to do and anything you want is within arm’s reach. Then you grow up, and you start disbelieving for other reasons.

But unbelief has its own comforts. You’re not in such a hurry to figure everything out if you’re not sure it will make a difference in the end, and you always figure if he does exist, and he’s the forgiving guy everyone says he is, you can still make it in under the wire. And hey, the world’s a big place, and there’s plenty of time to find something you can believe in—maybe on the other side of the world.

Then you go to the other side of the world and maybe you don’t find what you were expecting. You find something you’d just as soon not have seen. Then you come back and try to tell people about it, but you can’t. When you finally have a story to tell, you can’t tell it anymore because the person you were—along with the means you had for relating what you knew—is dead.

I should back up, though.

My name is Peter Neils—Nils originally, Scandinavian—I’m forty-six, and I’m a journalist. I’ve been in Nigeria and Sierra Leone, I got as close to Chechnya as they’d let me, and I was in the Gulf during the war, although by the time I got there most of the fun was over.

But that was when I was younger, still living down a bad marriage (high school sweethearts, seventeen, preggers, the whole nine yards—that’s how it gets in Wisconsin), and I was probably hoping half the time I would die. As I got older I cooled off. These days I mostly do short pieces for Vanity Fair and National Geographic—pictures of waterfalls and tree frogs, the sort of thing people like. Nobody wants to see a hole full of severed arms. But for some reason people like to look at pictures of glaciers.

No one is ever frightened by a glacier—although, perhaps, they should be.

I was once profiled in Esquire. The lady interviewer asked me a question I assumed was just conversational, but it later—to my immense chagrin—cropped up in the interview.

“What do you think,” she asked me, “should be the UN policy on intervention if the People’s Republic of China were to invade Taiwan?”

You see there were no other political questions, so I was thrown for a loop, although it was a hot topic then with the handover of Hong Kong.

“If that were to happen,” I told her, “I would personally enlist in the Taiwanese army and fight the Chinese. The UN can do what it likes, but Taiwan is a beautiful country full of lovely people, and I will die before I see those godless communists step one foot on its soil.”

I had imbibed some vermouth.

That whole “godless” bit was a joke: I’m still more or less godless myself (although I’ve flirted with the whole Buddhist thing, and my brother is very Catholic, which I respect). And it was more a sentiment than an expression of fact: if China were to invade I doubt the Taiwanese would be dumb enough to put up a fight, no matter how seriously they take their army. I just liked the idea, and I liked how it sounded, and there it was in print in a little red insert. My fifteen minutes, and I’d come off like an Internet wack job.

Not that I didn’t get support. A lot of people felt the same, it turned out, but I’m not a radical by nature—I’m an observer—and besides, this isn’t the Spanish Civil War; the days of Hemingway and heroics are over. Hemingway had a line about heroics being over, and how you die like a dog, but at least then you could still fight—even if it didn’t mean anything. These days the gap in this world between the helpless and the heartless is wider than ever.

I’d first been in Taiwan—Formosa, the “Island of Treasures”—in ’96. That was after the big chill when I got back from Russia and started looking and thinking hard about my life, and I spent six months there and six months in Japan. Japan was alright but it was Taiwan that really got to me.

The Taiwanese are good people. Maybe it’s patrician and colonial, but you feel sort of protective. They have all the nice-ness of the Japanese, but more relaxed, more friendly, and without the vague doubt that their ancestors might have tortured your ancestors in POW camps (or, to be fair, that your ancestors dropped bombs on theirs).

In Taiwan, when you want to call someone over, you hold your hand out palm-down and waggle your fingers. That took some getting used to. Also, when you’re a guest, after you and the host have put away some of that strong Chinese liquor, it’s polite for him to sing a song for you, and vice versa. That was my favorite part. I got a kick out of listening to Taiwanese businessmen mangle the words of Beatles songs—which they assumed were what I liked as an American. I think a lot of people in Asia assume the Beatles are American. But my principal host, Mr. Lueng—a fellow journalist I’d met on assignment in Nepal—taught me a traditional ditty that goes something like this:

When someone punches me,

I fall down;

When someone spits at me,

I turn my head;

When someone yells at me,

I don’t get angry;

It’s less trouble for me

And less trouble for them.

That is a very—I don’t want to say Asian sentiment unilaterally, but it fits a number of countries, not just Taiwan. Whereas it’s not a very American sentiment.

I often find it going through my head when some nine-thousand-pound lady is hogging all the dryers at the Laundromat.

For years my life got quiet. I brought in a paycheck; I went out for drinks with old friends; I started seeing a woman, although it didn’t work out. In ’98 for Vanity Fair I landed a big interview with Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury. I think they were right to send me and not Chris Hitchens. They liked the piece, and people—mostly religious people—wrote in to say my treatment of him and my questions were respectful. So for a short while I got a reputation as a religion guy, and in 2000 they sent me to do a piece in Taiwan on Fo Guang Shan.

Now, Fo Guang Shan means “Buddha’s Light Mountain”; it was founded back in the ’40s by a refugee who’d come over from the mainland. To hear them tell it, he’d built it with his bare hands out of nothing, and now it was the largest Buddhist organization in Taiwan with branch temples worldwide. It was in the Chan lineage, but as far as I can tell, all those places are like Protestant churches—more or less the same.

The order’s founder was still alive but in Singapore, so I toured the main temple, spoke a little with the current abbot and a few of the venerables and some of the students at their college. It was a whole compound with an elementary and a high school. I say compound but I don’t mean to make it sound cult-like. Everyone there was nice, and if there’s one thing about Buddhism I’ve observed: stated positively, you don’t have to believe anything you don’t want to. Stated negatively, you can’t believe anything at all—if you’re a foreigner they tell you what they think you want to hear, and I imagine it’s the same for initiates. If you believe in God they’ll call the Buddha-nature God. If you believe in science they won’t mention rebirth, hungry ghosts, or the hells. There’s a doctrine—uppaya in Sanskrit, hoben in Japanese—that’s translated “skillful means,” which says that truth can be expressed in any number of ways and has to be expressed in different ways to different people, and in Japan they have a saying: uso mo hoben, meaning a lie is skillful means, too.

That’s kind of a pussy tactic, if you ask me, but at the same time you have to admire the balls on a theological doctrine that essentially says it’s okay to lie. And maybe after all that’s not such a bad thing when standing by your principles means strapping a bomb to yourself and blowing up the other guy.

I came there to report on the temple. I did the piece, and I turned it in, and I’ll see if it gets used. I ended up reporting on something very different.

But first, something happened there that seems important now.

The temple didn’t have a reception desk, only a big gaudy fountain-statue of Quan Yin Bodhisattva taming a dragon, and the venerable who was supposed to meet us had gotten his wires crossed, so—because it was a nice day and a beautiful temple—we started wandering. I was there with my cameraman, a young guy from California named Pickett, shaved head and a couple of bracelets on both arms. I had never worked with him before and I could tell he thought I was old-fashioned. Pickett fancied himself a Buddhist and had a mandala tattooed up his back that you could see on his neck.

Pickett was appalled by those giant Technicolor statues: “It’s fucking Taiwanese Disneyland.” I guess he expected they’d all be living in abject holy poverty, and I could have explained to him that that sort of thing doesn’t bring in the acolytes. Was this skillful means, these statues, or was it skillful means to package Buddhism to Americans as some pragmatic philosophy? Did anyone know? Maybe the founder, but he wasn’t telling.

“If the Buddha could see this shit he would cry,” said Pickett.

Just to get him mad, I bought about fifty good-luck charms at the gift shop and hung them on my neck and my wrist, and I tried to hang them on his camera. He just looked away and muttered something about superstitious fucking bullshit.

The venerable we were looking for was a teacher at the college, so eventually—after a few bubble-teas at their café—we consulted a map and headed in that direction. The temple wasn’t that large but as stupid Americans we got lost immediately. Instead we ended up inside the girls’ high school.

The two girls we bumped into weren’t shocked or shy at all; in fact, they thought we were teachers, and it took work—pointing at Pickett’s camera—to get across that we were journalists. My Mandarin is frankly lousy, and Pickett’s was nonexistent—we were counting on them to provide us with a translator—and while most Taiwanese take something like seven years of English, these girls were only so far along in their education. Next we managed to hash out the word “college,” upon which they immediately and cheerfully agreed to take us there.

I wondered if they just wanted to cut class.

To be honest, I don’t recall much what they looked like. But I think all Asian girls below a certain age are cute. Call me what you like, a racist or a pervert, but it’s like I said: you feel sort of protective. I do remember one of them wore a white T-shirt that, when she turned her back to us, I saw read, Drive away with me. Lot’s run away together.

Goddamn, I thought. But isn’t that a beautiful sentiment?

As we walked past the athletic grounds, they waved to their friends on the basketball court and yelled something.

“‘Do you like American men?’” Pickett whispered to me in spurious translation.

They took us by the back door of the college and one of them went inside, leaving the other alone with us, looking slightly nervous. We were standing next to a pool with big carp in it. Pointing at them, Pickett said, “Fish?”

The girl smiled and did a “swimming” thing with both hands.

“Yuu,” she said.

Her friend came back with an elderly man who looked like a janitor. He scratched his head as he looked at us, and more slow communication followed. It was about that time our guide found us, running down a slope and waving his arms.

After that it went off without a hitch.

But it was later, sitting in a noodle shop outside the monastery gates with Pickett, that he said I looked “pissy” I hadn’t noticed, but I gave it some thought and said, “You know, the more I think about it, the more I find that disturbing.”

“Find what?”

“Those girls. How they just went along with us, no questions asked.”

“You thought that was weird?”

“All I’m saying is, didn’t their parents ever tell them not to go off somewhere with big, strange foreigners? I mean, I know we’re both nice guys, but …”

“I dunno, man. It was like broad daylight.”

“Still. In New York even the rich girls have more sense than that.”

Pickett shrugged. “I don’t really have any interest in fifteen-year-old girls.”

For some reason I felt moved to respond quickly, “Well, me neither.”

I can’t remember what turn the conversation took after that—but we let the subject drop.

We had finished up by late evening and hopped the bus back to Kaohsiung. Taiwan is a small country, but it amazed me that a temple that was technically in Kaohsiung was still an hour’s bus ride from the center of downtown. The one thing that has continually impressed me in every part of the world is the sheer number of people in it, the distances in between them.

This is an aside, but my brother Tom, the Catholic missionary, married a Chinese girl, and when her relatives came to visit us in Milwaukee they got out of his car, took a look around at what is by American standards a pretty big city, and remarked—looking quaintly pleased—that it was “just like the provinces” in China.

Kaohsiung is a sprawling commercial city, although nothing compared to cities on the mainland I’ve seen. There is no discernible rhyme or reason to it, and we walked from our hostel until we found a bar—it took all of two blocks—where we bought cheap, badly filtered Chinese cigarettes and cheap domestic beer. It is highly possible to get nice things in Taiwan, but I think we both wanted a sleazy experience in keeping with the smoggy and crowded Kaohsiung atmosphere. Every Taiwanese, his sister, and his cat owns a motorcycle. There were six motorcycles parked outside the bar—presumably because there’s slightly more room than in China, where the bicycle is preferred.

We had two days to ourselves and we were pondering what to do with them. We’d gotten to like each other well enough that we planned to stick together. The sight of the temple had cured Pickett of his spiritual aspirations vis-à-vis Taiwan and now he wasn’t sure about seeing more temples. There were some nice ones in the mountains, I told him. I had once waited for several hours outside a combined liquor store and poultry farm to hitch a ride on a flatbed truck to a mountain temple. He wasn’t so sure about that, either, so I asked if he had ever seen Taroko Gorge. Of course he hadn’t seen Taroko; it was his first time in Taiwan; but I was drunk. “You have to see Taroko,” I said. “It’s gorges.” I think I stole that pun off a bumper sticker. Taroko Gorge is Taiwan’s national park, closer to Taipei at the northern end of the island than to Kaohsiung in the south. It’s four hours by bus from Kaohsiung, no longer than from New York to Boston. After we saw it, I told him, we could do the rounds in Taipei; I’d look up friends there and we’d have a grand old time. This struck both of us as a sound plan, although at that point buying two motorcycles and driving them into the sea might have seemed like a sound plan.

After that Pickett struck up an acquaintance with a local girl who may or may not have been a prostitute. Now, I’m no pickup artist, wasn’t even when I was young—residual Catholic guilt, I suppose—but it’s not like I objected. She looked young (no interest in fifteen-year-old girls?), but let’s be honest—who can tell? They went off somewhere, and I made my way unsteadily back to the hostel. I’ve picked up snatches of poetry in my time, and one of them came back to me then:

There Wealthy Meg, the Sailor’s Friend,

And Marion, cow-eyed,

Opened their arms to me but I

Refused to come inside;

I was not looking for a cage

In which to mope in my old age.

I stayed up, getting sober and smoking off the balcony. I called a friend in New York and told him how the journalism had gone: for him it was almost noon. Pickett came back at past three in the morning looking drawn and confused. Although I was jocular about it, he wouldn’t talk about what had happened. He had money the next day, so I figured at least he hadn’t been robbed. I guessed it would always remain a mystery.

When it got light we hopped a cab to the station and got on the bus to Taroko.

My fondness for Taiwan might be due to the fact that my first vacation there was the first real vacation of my life. On assignment I had worked constantly—I had a real work ethic then—in the middle of grimy, noisy, sometimes dangerous situations, and I drank more heavily so that half the time I was all business, the other half nothing at all. Before that I had grown up in Milwaukee and New York, natureless cities of great industry. So I remember that first bus ride from Kaohsiung to Taroko Gorge. The road goes straight up the seaside cliffs, under arches of natural granite, and the bright blue Taiwanese sea is enough to kill the breath in you. The size of those cliffs is incredible and on a clear day there is no dividing line between the blue sea and blue sky and it looks like the mouth of God. And seven years later, it was just the way I remembered it.

To me, after that prelude, the gorge itself was somewhat of a letdown. But how could it have lived up to my expectations? The first time that ride along the edge of the sea felt like the antechamber to some other world. We just never got there.

Of course to my companion, of San Francisco, a gorgeous seaside drive was nothing new.

Pickett was surprisingly uninterested in my old war stories. He didn’t ask about the time I had photographed a family of alleged drug dealers lying in their blood, shot at their breakfast table by the Nigerian police. In his presence I felt younger and probably acted it, so we talked about drugs, and the Doors, and Graham Greene. Pickett was a great reader and a graduate of Bard College. We joked that to find another drinker in the journalistic profession was no great providence, another reader more so.

He was newly enthusiastic about books I hardly remembered reading; also about ideas I knew to be ill-advised.

“One day, man, hell, maybe when this job’s over, I’m’a go to Jamaica, smoke it up with the Rastas.” Noticing the incredulous look I gave him, he quickly amended, “Look at you there, sittin’ lookin’ at me like I just listened to one Marley record. I got friends went there, they say the grass’s so strong—”

“Damn right,” I said. “It’s so strong it fucking paralyzes you. That’s when you say something dumb and it gives them the excuse to shoot you in the head.”

“The hell you mean—? The Rastas ain’t gonna shoot me. Whatever happened to One Love?”

“I don’t know what happened to it. But they shoot tourists now, and that’s a fact. Take it from me, I wouldn’t go there without a very reliable local guide.”

I’d heard as much, although it had been years since I’d smoked.

You started to see the signs for Taroko long before you got there. This heightened that unbearable anticipation I’d felt the first time, along with a directional sign that read—I swear to God—to the “promised land.” I don’t know if this referred to Taroko or to some other place. In any case the whole area was a bit strange. There kept being bigger and bigger cliffs, and you wondered, is this Taroko now …?

But as I said, when you got there it was a letdown. The bus let us off nowhere in particular, by a rest stop, the other tourists wandered off, and Pickett looked around blinking.

“We here?”

I nodded. “We here.”

“Big rocks,” he said, as if to humor me.

We weren’t yet in the gorge proper; there were still the mountains on either side of us. The gorge itself only substituted sheer rock for the foliage.

“Big rocks,” I said.

He began to unpack his camera. “I bet I could get some good shots here. Maybe sell ’em someplace else …”

“Or just put them in with the piece. We can say we took them at the temple; they’ll never know.”

“Hah. Yeah. Dumb fucks.”

“Dumb fuckin’ fucks. Howie,” that was my current editor, “thinks all East Asia is just one big jungle around a temple. And Tokyo.”

We were both a bit vague with our hangovers, in the bright sunlight all of a sudden.

We lit up Double Lucky cigarettes from the bright red cartons. Double, lucky, and red, all the constituent elements of Chinese culture. It crossed my mind that the Chinese emphasis on luck was just about as far from Buddhism as you could get, even further than Christianity. At least they both had an element of providence. But there it went with the skillful means again.

Pickett touched his head. “Pete, I’m not so sure about this. This whole getting off the bus thing. You ever see Apocalypse Now? ‘Stay on the bus, man’?”

“Walk,” I said. “You can walk most of the gorge, and on the little trails the bus won’t go down. It’ll be good for you.”

“Fuck, man. I ate all vegetarian yesterday, I dunno.”

“I thought you ate all vegetarian every day. Fucking Buddhist hippie.”

“I try,” he said.

“You stay on the bus, they drive so close to the railing you swear the thing is going in the drink. It leans, man. Fifty feet straight down to the water. Railing a foot high, made out of tin. The Taiwanese are crazy; they don’t care; they’ll drive you anywhere. They’ll take you anywhere in the back of their truck. They just say Omitofo and that’s the end of it.”

Omitofo was Amithaba, the Buddha of Infinite Light. He was popular in East Asia, so much so that he made Sakyamuni look like a chump. Reciting his name was supposed to protect you from snakebites, rockfalls, all kinds of things; another thing that had rubbed Pickett the wrong way at the monastery.

“It’s true there ain’t no seatbelts on those buses,” he said. “I dunno.”

“Walk. Take your pictures.”

“I’ll take my pictures.”

His camera was old but good, a Nikkon F SLR. I’d seen those cameras before in places where they got dropped or even shot at. I guessed an uncle or something had passed it down to him.

We swung by the visitors’ center, where I heard people speaking Korean and Japanese (both languages I had a better grasp of than Mandarin), and there was a big relief map of the gorge as high as your waist. Pickett whistled.

“To make it look good they show the whole mountain range,” I said. “We’ll just be down in this part here.”

They also had a few stuffed specimens, all of them aged and a bit sad-looking, of local fauna.

“Damn,” said Pickett, looking at a viper with seams showing in its open mouth, “I wanna see a snake. They don’t have snakes where I’m from.”

“Nor where I’m from.”

“You think we’ll see one?”

“I don’t know if they have snakes. Squirrels they have. I mean the snakes are out there but they’ll keep their distance. Don’t fuck with them and they don’t fuck with you.”

“Shit, just like me,” said Pickett. “That’s my kind of animal.”

Before we set off we bought a four-pack of Yuenling lager from the store, which Pickett carried in a huge plastic sack.

“Hey, man. You think you could make it all the way from one end of Taiwan to the other, just drunk all the way?”

“Omitofo,” I said, and we both laughed.

“Fuckin’ Omitofo.”

As we went down the path, Pickett moving with wide, swinging steps as the lager bounced on his hip, he started to sing a song of his own invention to the tune—very, very roughly—of “Dixie”:

Oh I wish I was in Taiwan

It ain’t China or Japan

And they got big cheesy statues

That they worship like they’re idols—

Oh I like to be in Taiwan

I drink cheap beer all day long

And something, something, da na na—

Omitofo, Omitofo

Omitofo, you motherfuckers

I got this motherfucker with me

His name be Crazy Pete

I just made up the “Crazy” part

But he’s pretty fuckin’ crazy

That dude says he was in the Gulf

But I don’t know ’bout that

Next he’ll tell me he cut off Saddam’s ass

And wore it like a hat….

I joined in for the last chorus:

Omitofo! Omitofo!

Omitofo! You motherfu-u-uckers!

We got a few strange looks, and, guilty, I quieted down.

I’m getting to the important part. I should be careful.

It was a Tuesday, so the paths weren’t too crowded. The last time it had been Sunday and the buses had been crawling down the roads. We took a footpath up through the jungle, behind a Korean family with two young boys, and the mother kept yelling at them not to touch anything. Halfway up the rise we both started wheezing because of the cigarettes and I doubled over.

“Stupid old man,” said Pickett.

His mood was improving.

The bright, hot Taiwanese jungle. All of this so close by the road. Everything seemed painted in one pure color—green leaves, blue sky, red flowers. Birds calling. Some furry thing scuttled into the trees before I could get a good look at it.

“Nice weather,” said Pickett.

“Isn’t it?”

He set down the lagers and we each cracked one open. We sat on a rock that looked like Oreo ice cream and all of a sudden Pickett jumped up, shot lager across the path, and yelled.

Across from us, between two trees so far apart that it might have been levitating on its own power, was the biggest spider you had ever seen. Well, evidently the biggest spider Pickett had seen. Its body was black and yellow and it had legs as long as fingers.

I laughed into the mouth of my bottle. The spider was perfectly still.

“Man, I told you,” already adopting so thoroughly his way of speaking. “Don’t fuck with them and they won’t fuck with you.”

“Fuck, man,” he said, wiping a stain on his jeans leg. “Scared the fucking shit out of me. Thing’s big as my fucking head.”

“He’s just chilling out right there. He’s cool.” I raised my bottle to the spider. “I drink to you!”

“I fucking hate spiders.”

“Hey, hippie, don’t you think that was some dude in its previous life?”

“Fuck you, man. Maybe a real nasty-ass person. Like Jeff Dahmer.”

He sat back down, his legs shaking a little. The spider was about five feet away from us.

“Have a drink.”

“I will have a drink.”

I love the way that alcohol and nicotine combine in your blood. When I drink I want to smoke, and when I smoke I want to drink, but I’m still alive. I lit another Double Lucky and so did Pickett.

For a second it seemed like I’d found that paradise after all—the one that was always just around the next bend. Always like that. There one second; the next, gone.

Kyoo-kyoo-kyoo, went the birds.

“So you love snakes,” I said, “but you’re terrified of spiders.”

“Not terrified, I just hate the things.—When do we get to see this gorge, anyway?”

“When we get to the top we can look down on it. It’s a long way down. The river should be shallow this time of year.”

Then I heard them.

I want to put down the song they were singing. I know four languages pretty well—English, French, Russian, and Japanese—and I taught myself Japanese when I should have been learning another language, in southern Nepal, where it was the only educational book in that sad little dry goods store. It came in handy later. The chorus was all I remember hearing:

Tongara gatta sekkai

Hikkuri kaeshi

Hikkuri kaeta sekkai

Hoppori dashi de

Meaning: Turning the confused world upside down. Tossing away the upside-down world. Then:

Hai, sarabai!

Hai, sarabai!

Hat, sarabai!

Now sarabai, as far as I can figure, is a strange pun. But then it was a strange song. Saraba is a slangy Japanese way of saying good-bye. Bai is just bye, as in bye-bye. I had never heard the word and at the time I didn’t get it.

Three girls came into view holding hands and swinging their arms and skipping, as much as this configuration—and the narrow path—allowed.

Three young Japanese girls in sailor-suit uniforms. Blue-and-white jackets, blue skirts and red neck ribbons. My lager went down the wrong way and I choked, the colors were so sudden.

On instinct Pickett and I both moved our beers into less obvious positions. There we sat: two dimwitted foreigners, blinking in the sunlight. Against us they were brilliant and quick. Like fish, two of them darted behind the tallest one.

The tall girl covered her mouth and laughed. She had slightly wavy hair coming down on either side and framing her face, and a yellow hair band: this I remember clearly.

I swallowed a burp, a painful feeling, and said, “Ossu,” meaning, Yo.

Her face brightened. “Speak Japanese?”

“Un, chotto dake.”

“A-aah umai deshou!”

Of the other two girls, one was sort of plump and had a bowl haircut; one was slender and had long hair.

Pickett punched my shoulder. “The hell you waiting for, man, introduce me to these fine ladies!”

But that phrase brought me back to earth. Feeling strange, I looked down and shook my head.

He put one hand on his chest. “Pickett!” he said.

“Pikketto!” the girl shot back at him, like she was spitting. Her cheeks were full of mirth.

“Suman,” I said, cutting my head at him. “Kochira baka da.”

I think Pickett guessed what that meant without my telling him because he punched me again. The girls laughed. It was bright on the path and their laughter was also bright.

“Kiotsukero, kimi,” I said. “Hittori dakara.”

“Ee yo.” She flapped one hand. “Ee yo.”

Although it wasn’t exactly right, I had told her to be careful because she—they—were alone. She’d told me there was nothing to worry about.

Pickett raised his camera. “Smile, now! I’m a big photographer from Time magazine; I’ll make you all famous!”

The other two were bolder now. All smiling, they threw their arms around each other’s shoulders and flashed us V-signs. The camera snapped. All of a sudden one of the girls—the plump one—broke from the others and ran a ways up the path.

“Taeko-chan matte!” yelled the tall girl, then, as she passed us, flashed a last smile.

“Sayonara, Pikketto-san!” said the third girl and gasp-laughed and bowed.

“Sarabai!” the tall girl called back.

“Hai, sa-ra-bai!” came the voice of the one apparently called Taeko-chan.

“Sarabai!” said Pickett, waving vaguely, thrown by this suddenness. But he should have known that’s how young girls are, darting from place to place like cats, like birds; like nothing so much as young human girls. Beautiful things flit through our lives like that. Other things, like Taroko Gorge, are just there.

“Cute,” he finally said.

“Cute,” I agreed.

“Man,” he said, “real Japanese schoolgirls. Fuckin’ A.”

I arched an eyebrow. “I thought you said you didn’t have any interest in fifteen-year-old girls.”

“Well, no,” he said quickly, “but I have friends who might.”

I laughed.

“Hey—Crazy Pete. You got kids, man?”

“One. Boy.” I pulled out the wallet and showed him the pictures. Steve. They were old pictures; Steve when he was ten, twelve years old, in the backyard.

Pickett laughed. “Motherfucker looks just like you. What’s he up to now?”

“Dunno. I haven’t seen him in years.”

“Oh. Man, I’m sorry.”

He stood up and hefted his belt.

“I gotta take a leak.”

“Knock yourself out.”

I took a pull on my lager.

“I’m sorry, man,” he said. “That shit’s heavy.”

“Tell you what …” I shifted my back up against a tree, and my eyes wandered up to the speckled leaves overhead. “Take your time, why don’t’cha. I might just doze off here.”

“Shit. Well, don’t get robbed.”

I hadn’t been serious—but while Pickett was gone, I must have fallen asleep. Here I’m not so clear on things. My head started aching a little when he asked about Steve. But that was no surprise; I had gotten next to no sleep the night before, and I was hungover and freshly—if only slightly—drunk. And I suppose it’s normal not to be able to tell exactly when you fall asleep, let alone how long you sleep for. It could have been a minute or ten minutes.

All I know is that at some point Pickett came crashing back through the trees, wiping what I assumed was vomit off his chin. I was surprised he’d venture so far with that spider still hanging across from us.

“Sorry, man,” he said, grinning. “Guess last night caught up with me.”

Immediately I realized what had happened and looked at my watch, but I hadn’t checked it before I’d dozed off. It was seven past three in the afternoon.

“God, we pissed the whole day away. Come on if you want to see the gorge.…”

So we climbed the hill, and we saw it. We stood on the rock looking down into that roaring pit. There was a wooden railing as high as your waist. The slope was gradual, but at that height it was still frightening. A sheer drop on the other side, just a wash of white stone as tall as most New York skyscrapers.

An elderly Taiwanese man came up beside us. Pickett and I turned away. We hadn’t seen the Japanese girls but the path had branched a few times.

“Should we just go back?” he said.

Maybe it was the light behind him now, but his face looked hard.

“Hey, man. You okay?”

“I dunno.” He shook his head. “Still feel kinda sick, honest.”

I imagined what, then, it must have been like for him to look down into the gorge, and I felt a chill myself. “Sorry.”

“It’s cool, it’s cool.” Then he laughed and said, “Big rocks. Whoo.”

“Big rocks.”

As we went back down into the shade of the trees, away from the sound of the water, he recovered a little. He began to talk easily, if unhappily. “I dunno, man. I don’t think it’s the booze, man; I think I got that out of me. It’s just being here, y’know, out of the States. I guess it’s caught up with me. I been away before and it’s always the same. And those fuckin’ statues …”

“Just homesick, huh?”

“Something like that, I guess.” Then he added with sudden warmth, “Hey, thanks, man. You’re a good guy, y’know?”

We heard a cry far off. Sharp but still indistinct.

I don’t know why, it wasn’t that unusual, but maybe just because of the awkwardness that follows when one man expresses affection for another, I tilted my head to listen, and so did Pickett.

The cries were coming closer. They didn’t sound quite like a distressed person. There were several voices.

I tapped Pickett’s arm and we started down, him with two bottles of Yuenling still in the sack.

I made out “Kari-chan, doko?”—a girl’s voice.

Kari, where are you?

Then a boy: “Oi, Mori! Joudan janee yo!”

Mori, this no joke.

The girl again: “Onegai, onegaishimasu!”

Please, oh, please.

Then, although I should have known already, came what stopped my heart: “Taeko-chan, onegai!”

There was pain in that voice.

I jumped—but it was only Pickett’s hand on my arm.

A moment later the boy appeared in front of us, wearing a school coat, scratching his head. He looked big for his age. He took us in unsurprised and said in fair enough English, “Excuse me. Have you seen three girls?”

Pickett and I exchanged a look. We had to admit we had. And then the whole business started.