Читать книгу Taroko Gorge - Jacob Ritari - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

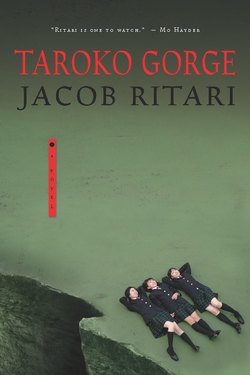

MICHIKO KAMAKIRI

ОглавлениеThe first time I got caught lying, I was in third grade and I took a pair of scissors and cut the heads off all my mother’s sunflowers. I think it just got on my nerves: Where did they get off looking so happy? But I told her I saw our neighbor Mrs. Nomura doing it because there was always a war over who had the nicer yard. Well, the war got a whole lot worse, and they were yelling at each other all day. Finally I felt so bad I started crying and told my mother everything, but I couldn’t tell her why I did it. I know why I lied—because I couldn’t tell her why I did it. She slapped me and told me I wasn’t a human being. Then later she felt bad and let me eat some roll cake.

Okay. Here goes.

I didn’t want to go on the stupid trip anyway. To make matters worse, they stuck me on the bus next to that creepy Bug. I was lucky, though, because I didn’t have to be the one to ask if we could change seats: Chizu Sato asked first. But she’d gotten the seat next to Seiji Sumiregawa, and everyone thought she was crazy because everyone knew Seiji-kun was a total hunk—one of the top three in class A—but I knew she was just using reverse psychology because she liked him but wanted him to know that she didn’t want him to know that she liked him. Someday I’m going to write the psy-ops book for junior high girls because God knows, just telling someone you like them, you might as well be committing suicide.

No, said Mr. Tanaka. No changing seats. Make a new friend.

Mr. Tanaka is such a loser. Who’s actually named Tanaka? You never hear about any Americans named John Smith.

What did he mean, make a new friend? It was the stupid senior trip. In a month we’d all graduate and go to high school. If we were going to make friends, we’d already made them. And nobody, at least no girl, was ever going to be friends with Bug.

I guess his name was Keiichi Hirata, but he collected bugs and he looked like a giant bug himself: so, Bug. It started back in sixth grade, when we each had to collect twenty of them for the science project. Twenty was too many for stupid downtown Morioka, but Ms. Kazan was a mean old slave driver. All you got were cicadas, cockroaches, and a few weird flies—no spiders because spiders aren’t bugs, but that didn’t stop a few kids from bringing them anyway. If you brought eighteen, that was an A-minus; fifteen was a C; and so on. If you brought ten or less you failed. But Bug brought in nine, and the one he was most proud of he kept in a little paper bag so no one could see. Taeko Maeda, that happy girl, begged him and begged him until he finally showed her. But he would show Taeko-chan because even then he liked her. He probably kept it in that bag just so she would beg him to show her, since she sat next to him. But when she saw it she started crying. I’m not kidding: real, superbig tears.

Everyone crowded over: Taeko-chan doushita no?

It was a rhino beetle as long as your finger, glossy, like a stone. There was a green pin stuck in it where the wings met the body.

Taeko kept crying and asking him how he could kill something so beautiful.

You’d think that squirt would’ve learned his lesson that bug collecting wasn’t something that made girls like you, but it got worse. I only know because he brought his box into class sometimes and the teacher would yell at him. Okay, I admit it was sort of interesting, and I’d take a peek over his shoulder. He had moths in there, beetles in all kinds of colors like designer stuff, spiders as big as your face.

Okay, I didn’t hate him. Maybe I even liked him better than other girls did. I mean, I don’t think bugs are gross or anything, although I don’t like the idea of sticking a pin through one any more than Taeko did. It’s just that this was the senior trip and this was the last chance to do a love confession before we’d all go to high school and work ourselves to death—on a senior trip the success rate for love confession has got to be like 95 percent—and that bus ride was something precious, you understand; it was a whole two hours you could spend with anyone … getting to know them.

Tohru Maruyama, the Class Rep. Rank: A-plus.

Tall, handsome, kind. The perfect gentleman. Maybe too perfect a gentleman. I don’t think he’d ever even been on a date because we all would have known. Probably the kind of guy who would never figure out when no meant yes. In the final analysis a big No Way. There were at least six girls after him, and I’d have to take my place in line, and besides, everyone knew he liked that weird witch-girl, Kari Hiraoka.

Jin Sul-Kim: the Korean athlete. Rank: A-minus.

He’d transferred in in the ninth grade. There’s a lot of prejudice against Koreans and I don’t think it’s right, but no one was prejudiced against Jin-kun. He had more muscles than he knew what do to with; first in track and a soccer player, and not stupid, either. Not as nice as Class Rep but not exactly mean, just kind of standoffish. The kind of thing some girls like. But stupid Cow-Boobs Sakura was going for the push with her stupid breasts—where did she get those; I think she must be Hawaiian—and she’d landed the seat next to Jin-kun on the bus from the airport to the hotel in Taipei, so she’d pulled a huge tactical lead. I think in such cases a strategic retreat is called for.

Seiji Sumiregawa: brains and a ponytail. Rank: B-plus.

They didn’t like long hair at the school, and if Sumiregawa hadn’t been the top male student in class A, I doubt he could have gotten away with it. He wasn’t much in the rest of the looks department—his chin was too small—but the ponytail turned girls’ knees to jelly. Also he told jokes and seemed experienced (although I don’t think he was exactly, if you know what I mean).

Outside the top three, the prospects weren’t good. There were a lot of losers in our class, and a lot more cool girls than guys, which was, tactically speaking, Bad News.

Michiko Kamakiri: the nondescript. Rank: C-plus.

No matter how much I eat, I’m skinny as a pencil. I guess some girls would kill for that, but I’m turning sixteen in two months and I want a stupid figure already. My grades are average and all I can do is play the stupid clarinet. You see? I’m honest. Maybe that’s my good point. I do think my face is okay, though, and I’m tall, which means legs.

No question: it was Seiji Sumiregawa or bust. I’d push him down if I had to—there were still two days left—but I was stuck on the bus next to Bug with his huge glasses and his stubby little legs, and I didn’t even want to go to Taiwan in the first place. Class A always goes to Taiwan, never Hawaii or Okinawa. There’s nothing fun in Taiwan, no diving or coconuts or anything. All we’d done so far was go to some temple and some museum where the prize of the collection was a cabbage made out of jade. Just this cabbage sitting there. Mr. Tanaka said it was one of the great treuares of Chinese art, but I think he was making fun of us. What are we, stupid?

The senior trip: the oh-so-brief mating season of the junior high class. Like those flies that only live for one day.

Bug was playing his Game Boy. He’d gotten the window seat. I was leaning over the back of my seat, ignoring him, talking to Mai Mori, who was sitting next to Taeko.

Mai-chan was boh—spacey—but nice. She was no competition: like they say, nice girls finish last. Mai-chan was short, had long hair and big eyes.

Taeko was in her own little world, too, listening to music and nodding her head. She looked just like a kitten. Girls like that will make great wives someday, but it’s girls like me who seize the day while we’re young. We were talking—me, Mai, and (ugh) Cow-Boobs Sakura, who was behind her in the very last seat of the bus, about boys we liked, but not any who happened to be in earshot, which included of course Jin-kun and (oh God why) the Class Rep, sitting chatting with Magical Girl Kari.

Sakura, pushing her boobs in Mai-chan’s face as she leaned over her, asked, “Hey-hey, who do you like?”

Mai looked back at her with those spaceship eyes. “Like?”

“Yeah, like!”

“Like, how?”

Sakura cupped her mouth and whispered, “Rabu-rabu.”

That love-love feeling. I sort of wondered when the language we used had come into being. So much of it was English, what had they called it before the English?

“Oh,” said Mai, “I like everyone.”

“Minna?” Sakura laughed. “It’s fine to like everyone, but you can’t feel rabu-rabu about everyone!”

“Why not?”

“Rabu-rabu is …” Sakura brushed her chin with one finger, “a special connection between two people …”

“Oh, I want a special connection with everyone, though.”

“But special is special!”

Sure, Cow-Boobs, you should talk about boys, when they never leave you alone.

“I want to know if we’re ever gonna see this stupid gorge,” I said. “I can’t believe we’re driving two hours just to look at some hole in the ground.”

Of course, if I was sitting six rows up where Chizu Sato was sitting now, next to the ponytail, the bus ride wouldn’t have been a minute too long.

“I wanna see the gorge,” said Mai. “I like lookin’ at big things; it makes me feel small.”

The thing about Mai was, too, she came from out in the country—rice farmers—and she had this real hick accent.

“You like that?” I said.

I hated it.

I tugged on one of Taeko’s earbuds. “Hey, Maeda. What’re you listening to?”

“Oh—hi, Michi! Did you want something?”

“I said what’re you listening to?”

All of a sudden I looked around and my blood froze. Standing there, with his pop-star looks: Class Rep Tohru Maruyama. It was like a mirage.

He scratched his neck. “Eh … Kamakiri.”

“Y-yes?”

God had answered my prayers! He was out there after all! All those nights I’d knelt down and begged for breasts and hips—not caring if it was the Christian God or the Jewish God or the Buddha; I’d strike my bargains with whoever would hear me, thanks—he’d done one better! Go on, laugh at me. Everyone laugh.

“Mr. Tanaka says stay in your seat while the bus is driving,” he said. “Sorry.”

“Oh.” I put on my best smile. “Ha-a-ai, Class Rep–san!”

He slouched gorgeously away. I fell back in my seat.

Sakura was giggling.

“Shut up,” I muttered, scrunched down, and crossed my arms. Bug’s Game Boy was beeping. Up at the front, Seiji-kun was probably saying to Chizu, “Oh, you like blah-blah-blah?—so do I!”

“We should be getting close.”

I looked around crazily. It took a minute to realize it was Bug who’d said it, without even looking up from his Game Boy.

“Oh,” I said. “Thanks.”

I guess … I felt like if I could get a nice boyfriend, all the things about me would kind of—snap into place. My face and my hair and the clarinet. All of a sudden they’d mean something—to him. He’d tell me things about myself I’d never known.

But … at the gorge Mr. Tanaka couldn’t keep an eye on everyone. We might spread out. Have some time to ourselves …

Chansu!

But they didn’t let us off the bus. It kept driving right through the gorge, so close to the railing that I was sure it was going right over the side. Taeko curled up in her seat and shut her eyes while Sakura pressed herself to the windows on the other side, going, “Wah sugo-o-oi!” Mai leaning over her shoulder, her eyes all bugged out.

Tohru came back again to beg us all to sit down. He was too softhearted to be a good Class Rep. I wondered what he and Kari were talking about up there—maybe she was busy converting him to her crazy religion. Bingo, that was it. Leave it to a girl like Kari to waste a golden chance like this.

Okay, I didn’t really hate Kari; she was just so weird. And the weirdest thing was that everyone loved her. It’s funny because her full name was Hikari, which means “light,” and that totally crazy New Religion she belonged to was called Mahikari, which means like “absolute light.” I don’t know if her parents belonged to it and named her that on purpose. Mahikari is the weirdest religion ever. Going to church, praying, I can understand that (and for a second I thought it had really paid off), but in Mahikari they do this thing called okiyome. You’re not even going to believe this if I tell you. They hold up their hands like they’re saying hello and healing magic rays are supposed to come out of their hands. Okay, all religions have weird stuff, but the people in them—people who were in Ms. Kazan’s stupid science class—don’t really believe that, right? But Kari believed it. She would give you okiyome if you asked her. She’d just smile and hold her hand over you. It might have been more convincing, I don’t know, if she’d actually touched you.

And of course sometimes it worked. That’s just the law of averages, right? One time the projector broke in Mr. Okada’s class and Kari walked right up and did okiyome on the projector. It started working again a minute later. Everyone was like, sugee na! and sassuga Kari-chan! When someone got a scratched knee they’d put their foot on a chair and have Kari do okiyome on it. They didn’t believe in it but they didn’t not believe in it. How stupid is that?

But maybe God—or Su-God, as she called him—did love Kari. Things certainly went better for her than they did for me. She wore a yellow band in her hair that had been blessed by the priest or guru or whatever of her temple or church or whatever. God, it drives me crazy.

And all of that would have been okay if she had just been a weird, dumpy girl. But she had the nerve to be tall and pretty.

Anyway, like I said, I don’t like big places: I don’t like feeling small. The gorge was pretty big, bigger than any street in Morioka. I could see it plenty without getting up. I just wondered when they were going to let us off the bus, and finally they did.

We crossed a bridge over the river and stopped in front of a Buddhist temple. Outside it was hot and dusty and too bright. Mr. Tanaka was standing with Tohru and the driver at the front of the bus. The driver was smoking a cigarette. People in Taiwan smoke a lot. We had all started to run and laugh and horse around, and Tohru, with an expression like Jesus on the cross, started walking toward us.

People were leaning over the edge of the bridge: Amazing! Wow! Too much!

I couldn’t decide which I thought was more ridiculous, this great big canyon—way too big for anyone to have a use for—or that little piece of jade, carved like a cabbage, that we’d seen in the museum. I guess all they had in common was being things. Maybe I just don’t like things.

The temple had a gift shop, like they all do, and a collection box, like they all do. I saw a boy named Takeda drop in a coin and pray. I went over, dug a ten-yen coin out of my pocket—what did Buddha care? I thought—chucked it in, and put my hands together.

Dear Buddha, please let me have a good time today.

It was kind of a milder prayer than the one I’d been forming in my head.

I looked over, and Mr. Tanaka was sitting on a railing smoking with the bus driver. He was sort of smiling.

I went into the main hall. It was just a square building like the school cafeteria. There was a gold statue of the Buddha, and on either side of him scary-looking Chinese guys with swords, and one of them had a red face. I’m pretty sure I don’t remember that part from when we studied Buddhism in the ninth grade. I went out again.

Taeko and some other girl were holding up little knickknacks at the gift shop like they were precious treasures and squealing over them.

I noticed something scary: the only one who looked as out of place, as squinty, as irritated to be there as me was … Keiichi “Bug” Hirata.

I started looking around for Sumiregawa. Points were scored when I saw Chizu with some of her friends at the soft-drink machines, and I went past them to where a little path went up the mountain. At the top of it was a funny tower, painted red, eight stories tall, and at the top of the tower, on the balcony leaning over, were three girls, including Ms. Big-Guns Sakura.

Jin-kun was standing at the bottom calling up (in his kind of broken Japanese), “Come down! Is dangerous!”

Sakura laughed and her boobs swung over the railing, like they might come loose and hit us. Feeling sick, I turned away—and there, right next to me, was Sumiregawa.

“Ever seen Vertigo?” he said.

There was no mistake. Ponytail was talking to me.

“I, I, I—”

Of course I hadn’t seen Vertigo.

“Yes,” I said.

He was squinting up at the tower. With his eyes closed like that he looked sort of amused, like a gentleman, like an English gentleman with a cane and a hat. I didn’t care if his chin was too small. I melted.

“I went up in there,” he said. “There’s a big spiral staircase. You know.”

“Oh, yeah, yeah.” I nodded.

Then he laughed, so I laughed.

Chansu.

Sumiregawa was smart. What could I talk to him about that was smart? The only book I had practically ever read was Musashi.

“Sumiregawa-san. So—you like this place?”

“I’m not sure.” He linked his hands behind his head. “I think all this—kitsch kind of represents a corruption of real Buddhism. Don’t you?”

“Oh, yeah.”

I didn’t even know what kitsch meant.

Then he added, smiling, “Hey, call me Seiji-kun. We’ve been classmates what, three years?”

“Sure—Seiji-kun.”

“Michiko-san—that okay?”

I nodded quickly.

“My friends just call me Michi. Or Mii-chan.”

“Am I your friend?”

I smiled. “Sure, if you want to be.”

“I think I’d like that,” he said in his sleepy way.

Thank you! Thank you! The power of just ten yen! And maybe, I thought then in the bright light, okiyome worked, and didn’t everything work …?

“Three years,” he said.

“And now it’s all gonna be over,” I said, proud of myself for actually saying something. “But I mean, we can still see each other—I don’t mean you and me, I mean—everyone.”

“I guess that’s right.”

Then a voice called, “Seiji-kun!”

It was like the sun went out. I turned around and saw Chizu at the corner of the main hall beckoning him. Beckoning.

“Ah. What’s up, Sato?”

“Just come here already!”

“’Kay. Hey, catch you later, Mii-chan.”

“Catch you later,” I said, standing and waving helplessly.

I stood there for a little while. All I could think of, to keep from dying, was that he’d still called her by her last name. Ha!

I didn’t know what to make of it, or of anything else, so I started walking back to the bus.

But on the bridge I looked down and couldn’t believe my eyes. There were people down there. And that wasn’t all: our people. The Class Rep was down there! Tohru Maruyama was standing in the water with his pants rolled up to his ankles, hands in his pockets, like a model in an ad. And I could see Kari’s stupid yellow hair band.

For another second magic seemed possible. It must have been thirty feet down to the river; there were no stairs or anything by the temple. Then I realized they had gotten down on the other side of the bridge, where the rocks sloped—and the world was boring again.

They saw me and started waving. I heard them calling my name. But they looked too happy down there. Kari with the light all in her hair. Stupid Magical Girl. It was like they were in heaven or something, and they wanted me to come, but I didn’t want to go to heaven … it was too bright outside. I should have stayed on the bus.

But I went down anyway, clawing my way down the rocks. I almost lost a shoe. How could they all be so crazy—and the Class Rep? Kari must have gotten to him. That was just the thing she would do, climbing down a cliff onto a riverbank. I walked on the bank of white stone, and I could feel the heat through my socks. There were big rocks jutting into the river. Okay, it looked different here, like on some other world. Like the moon, only there was water—like there was life, all of a sudden, on the moon. It was cooler, too. They were all sitting or standing on a flat rock, right out in the river, and they had all taken off their shoes and most of them had taken off their socks.

It looked like heaven, but then it looked like some kind of Buddhist hell, a Hell for the Lazy. Mai Mori was lying on her back with her socks off, her bare feet just baking there in the sun. And Taeko was there, too (not Sakura, thank God), still with those stupid cute buds in her ears. They were both pretty good friends with Kari, so I guess it followed, but I couldn’t trust them to keep an eye on her.

Then there was Koizumi, Class Rep’s friend—maybe his best friend, you saw them together a lot—sitting like he was meditating with his eyes shut. Not that I had any time for Koizumi; he was a shrimp, even if he had a cute face. But with the way things were going, God, who knew …

“Michiko-chan, yo-ho!”

Kari waved at me. I climbed on the rock but I didn’t take off my shoes.

“What’re you all doing here?”

Tohru looked around. “Isn’t it nice?”

“Class Rep!”

“It’s fine,” he said. “I’m here, right? I’m keeping an eye on you.”

“Class Rep’s keeping an eye on us,” said Koizumi, opening one eye.

“Mr. Tanaka’s gonna get so mad!”

I couldn’t believe I was in this position. It’s not like me, usually. But it just felt like something was wrong.

“If you don’t like it,” said Kari, nice as ever, “I was about to head back myself. You want to come with me?”

Taeko got up and yawned. “Oh, me, too. I’m so tired.”

Don’t do me any favors, I thought. I hate it when people put you in hock with them by doing something you never asked for.

Mai got up sort of suddenly and weirdly. But then everything was weird with her. She and Kari made a good pair. “I guess I’ll mosey back, too,” she said in that country way.

“Mai-chan?” said Kari.

“Yeah?”

“You were looking at that sky like you saw something you liked there.”

“Oh.” Mai smiled. “I reckon so.”

So the four of us trouped back up the hill. All I wanted to be was somewhere getting acquainted with Seiji Sumiregawa. Still I felt like I had done something good by getting Kari away from Class Rep, even if I still didn’t have a chance with him. When we reached the top I all of a sudden tapped her, and when she turned around said, “Hey, Hiraoka. Can you use your magic to give me some big jugs?”

It just slipped out. Taeko went bright red, and Mai giggled, but Kari just smiled.

Then she said, I swear to God, with a straight face, “You shouldn’t use okiyome for things like that.”

That was the last time I saw her. If I believe what they say, it might be the last time any of us saw her. Just when we were about to leave the temple, Bug—of all people—came huffing back, saying he couldn’t find them. The rumors built for a while and we all stood there, and Mr. Tanaka stood there and smoked. For him I guess it was still a question of their wasting our time. Class Rep went to look, and about fifteen minutes later—we were all whispering so loudly it sounded like one person talking—he came back shaking his head.

“Inai ka?” said Mr. Tanaka.

“Inain desu,” said Tohru. “Hiraoka-san, Mori-san, and Maeda-san.”