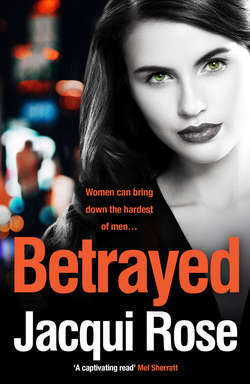

Читать книгу BETRAYED - Jacqui Rose, Jacqui Rose - Страница 8

Оглавление‘Come on out. It’s not funny now, Bronwin. Mum said we had to be back by seven. She’ll skin us a-bleedin’-live if we’re late.’ The tall skinny girl shouted loudly in no particular direction before looking down at her bitten nails, peeling off the last of the pink nail varnish as she waited for her sister to come out of her hiding place.

Exasperated, Kathleen looked up again. It was getting dark, and even though she’d known it was cold before she came out, she’d only put on a thin t-shirt. Better cold than looking frumpy in the brown coat her mum had bought her last week. The thought of bumping into any of the boys from the Stonebridge estate looking like something left over from a jumble sale made her shudder more than the evening chill of the October air.

Peering into the darkness, she could just make out the dark silhouette of her sister, Bronwin, scuttling about in the thicket of trees, thinking she couldn’t be seen. The girl sighed as she watched. What her sister found so exciting about playing in a stupid park was beyond her. Parks and swings and trees were for babies. And Kathleen certainly wasn’t that.

There were only four years between them, yet her only sibling seemed so immature next to her. Ever since she was little she’d felt older than her years. And even though she’d just started secondary school, she knew she wasn’t a silly little girl anymore. Not now, anyway. Not now she’d lost her virginity with the boy across the landing. Although it’d lasted less time than it took the kettle to boil, and he’d only just managed to get inside her before he’d exploded, groaning and coming everywhere, it still counted. Counted enough to make her special. For the first time in her life she had something to brag about.

Kathleen knew she wasn’t pretty like her sister, nor was she clever, and she certainly wasn’t popular. Everything was always a struggle. Everything she felt ashamed of. Even down to the way she dressed. Hand-me-downs from anywhere and anyone. Musty clothes ingrained with the stains and smells of poverty, which brought nothing but ridicule.

But that was all going to change now. The sense of being a born loser had gone. She was proud of being the first one in her year to do it and envious word had got around the class. Now, the girls wanted to speak to her and the boys didn’t avoid her any longer.

Looking back towards the trees, Kathleen realised couldn’t see her sister now. She wasn’t worried. This was how it always went. Her younger sister’s idea of a joke. Hiding and making her search her out. Letting her be on the verge of panic before she’d appear, grinning all over her face.

As she stood waiting, chewing on her nails, Kathleen thought about her mother who was only fourteen years older than her and had decided a long time ago that even though she’d given birth to two girls, she didn’t want the responsibility of caring for them, nor did she want the trouble of loving them; preferring instead to spend her time with any man who’d buy her a drink down the local. Kathleen shook her head in disgust and walked slowly towards the trees, resigned to the fact she was going to spend the next ten minutes searching for her sister in the woods.

‘Bron!’ She was getting pissed off now. She’d been looking for over ten minutes. Her arms had already been scratched by the bushes and she was certain something nasty had crawled down her top. She was cross, but she wouldn’t let her sister know she was. They both had enough of their mother being cross at them without her adding to it.

Kathleen heard a branch snap just ahead. Her eyes darted towards the sound. In the shadow of the night, she saw a dark silhouette a few feet in front of her.

‘Bron! Please stop messing, babe. I want to go now.’ There was no reply. She edged forward, feeling the ground as she stepped carefully through the bracken, when suddenly she heard the breaking of another branch. Only this time it was coming from the side of her rather than in front of her.

Kathleen listened, waiting to hear the stifled giggles of her sister. In the darkness she could hear breathing, but it didn’t sound like Bronwin’s soft breath. This breathing was heavier, and she turned in panic. The next thing she felt was the taste of blood as the stinging blow of something hard landed on her lips.

She screamed as she felt her top being torn and rough hands pushing her down into the damp cold earth, tugging painfully at her pants, under her skirt.

As she felt the hands tighten round her neck, her breath becoming short as the life seeped out of her, it was of some small comfort to the girl that the last words she managed to cry were, ‘Run, Bronwin! Run!’

Six-year-old Bronwin sat in the corner of the tiny room, watching the uniformed police officers milling about. Sitting by her was a plain-looking social worker.

‘Bronwin, you really need to tell us what you can remember.’

‘I don’t think she’s ready to answer any questions.’ The social worker intervened as the large detective leaned in to question Bronwin. Annoyed with the interruption, the detective snapped back, ‘I think that’s a matter for Bronwin, don’t you?’

‘Detective, she’s far too young to know what’s best. She’s had a traumatic experience and I don’t think these questions will help, do you?’

‘Listen, no one’s saying she hasn’t had a traumatic experience, but if we want to make sure the perpetrators can’t get out of this we need to make sure she tells us everything she can remember. She’s an important witness. Where’s the mother anyway?’

The social worker flicked through the notes. ‘We don’t know exactly where she is at the moment; we’ve tried leaving her a message but we’ve had no reply. She told us she’d meet us here, but maybe it’s all too much for her.’

‘She’s got responsibilities. This kid for one, and another one lying cold.’

The social worker bristled, furrowing her brow angrily as she took a sidewards glance at Bronwin.

‘That’s enough, Detective. Not everything is so clear cut. The family are well known to us and there are problems. The mother’s very young and, as I’m sure you’ll appreciate, things can get difficult for her.’

The detective sighed.

‘Fine, no more questions, but we need to take her to see the line-up. It’s important; we can only hold the men for so long.’

The line-up room was dark and Bronwin wasn’t sure what she was supposed to do. The woman who kept insisting on holding her hand smelt funny. A bit like the dusty old cupboard in the kitchen at home. She didn’t like the smell and she didn’t like the woman. She wanted to go home. Where was her mum anyway? She hoped she’d come and get her soon.

‘All we want you to do is tell us if you remember any of the men’s faces. We want you to have a good look and if you remember any of them, tell us.’

‘Can I have a word, Detective?’ A man with a loud booming voice appeared out of the shadows, making Bronwin step back behind the social worker. She couldn’t really make sense of the words he was using, but he seemed to be so cross; like everyone else around her.

‘Detective, my clients feel it’s unfair they’re not only being forced to be in the line-up, but that the “guilty” party will be decided on the say-so of a child. We all know what children are like. They choose things on a whim. I want a stop to this.’

The officer in charge rubbed his top teeth with his tongue. ‘If they’ve nothing to hide, they’ve got nothing to fear.’

The man grinned nastily at the detective, his eyes reflecting the coldness in his smile. Bronwin took a sharp intake of breath. She didn’t like this at all. Why wasn’t anybody taking her home to bed? She was tired and wanted to snuggle up with Mr Hinkles, the teddy bear her sister Kathleen had got her. Where was her sister anyway? She’d heard people talking about her and they’d asked her a lot of questions, but she hadn’t seen her since the woods. She didn’t want to think about the woods; thinking about them gave Bronwin a funny feeling in her tummy.

Big tears began to spill down Bronwin’s cheeks. Her eyes had adjusted to the darkness and she watched them fall onto the floor, right next to the man with the booming voice’s foot. Cautiously, Bronwin looked at him from underneath her shaggy fringe. He was smart and clean and smelled nice.

Bronwin quickly dropped her gaze as she saw the man looking at her. Her eyes wandered to his shoes. They were black shoes. Shiny black shoes, apart from the bottom parts of them, which were dirty with mud. She looked up again, edging back as the man bent down to meet her stare.

‘Would you like a hanky?’

Bronwin shook her head but the man insisted.

‘Here, take it.’ As he pushed the crisp white handkerchief into Bronwin’s hand she noticed some letters embroidered onto it, but she wasn’t good with letters, especially fancy ones that swirled and curled like those did.

‘Now, is everybody ready? We need to get on with this.’ The detective’s voice had a tone of weariness. He was tired and didn’t expect much from this line-up, even though in his gut he felt he had the right men; he knew only too well that with slick high-powered lawyers; like the one standing opposite him, even if the suspects had been caught with bloodstained knives in their pockets and the words ‘guilty’ written on their foreheads, there was still a possibility of them walking free.

‘Are you ready, Bronwin?’ The social worker pulled Bronwin up from her seat as the lights on the other side of the mirrored line-up room went on.

Bronwin nodded.

‘All you have to do is pick out the men who you think you saw in the woods. Do you think you can do that, Bronwin?’

Again, Bronwin nodded. She stood on a chair and in front of her a procession of men began to walk in through the door on the other side of the glass.

‘Don’t worry; Bronwin, they can’t see you or hear you.’

The men stood with their backs against the wall, staring ahead, holding up the boards they had been given. The detective adjusted the microphone as he spoke into it.

‘Can you step forward, number one, and then turn to the left and to the right, slowly.’ The tall man with dark hair stepped forward, nervously turning as instructed in both directions before stepping back to the wall.

‘Number two, can you step forward and then turn to the left and to the right, slowly.’ Without taking his eyes off Bronwin’s reaction to the men the detective stood up slightly as he realised he was too near the mike.

‘Number three, can …’

Bronwin’s mind wandered off. Her legs were getting tired having to stand up and she thought it was funny the way all the men were staring ahead. The lady had said they couldn’t see her, but she didn’t know how that was possible if she could see them.

‘Bronwin? Bronwin?’ The detective was talking to her. She didn’t know how long he had been, but she could tell he was cross; his cheeks were red like her mum’s cheeks went red when she was angry with her.

‘Do you recognise any of them? Were any of them there in the woods?’ The detective’s voice was urgent as he stared at Bronwin.

‘Detective, let me handle it.’ The social worker cut her eye at the detective. ‘Bronwin, do you recognise any of them? Were any of them there in the woods?’

Bronwin looked first at the detective and then at the lady. She didn’t know why they were asking her the same question and arguing about it.

The social worker sighed and looked at her watch. ‘Bronwin, this is very important. If you can remember anything, you need to tell us. Can you remember who it was?’

Bronwin nodded her head.

‘Show us then. Can you point them out?’

Bronwin nodded again, she raised her hand and pointed, speaking in a small voice. ‘It was him.’

The officer sprang into action. ‘Number eight.’

‘Yes. And him.’ She pointed again at the line-up.

‘Number two.’

‘Yes.’

The detective’s face didn’t give anything away. In a matter-of-fact manner he said, ‘Well done, Bronwin. You’ve done great.’

Bronwin looked at him, her elf-like face turned to the side. She swivelled around, turning her back to the line-up and staring towards the door where the man with the booming voice stood. ‘And him. I saw him in the woods as well.’

‘Bronwin do you understand what happens to children who keep telling lies?’

‘I ain’t lying, Dr Berry. It was him, it was that bloke. Why won’t you believe me?’

The psychiatrist tapped his pen on his leg absent-mindedly. ‘We’ve gone over this before and we both know why I won’t believe you, don’t we?’ The psychiatrist paused dramatically then said, ‘Because it’s simply not true. How do you think a person feels to be accused of bad things, Bronwin? How would you feel if I accused you of doing something bad?’

‘But you are. You’re saying I’m lying.’

‘That’s not the same, Bronwin, because you are.’

Bronwin’s eyes were wide with fear as she cuddled Mr Hinkles, her teddy bear. ‘Please let me go home. I think I should go home now; me mum will be missing me.’

Nastily, Dr Berry spoke in a whisper. ‘Bronwin, children who tell lies, especially vicious ones, don’t go home. How would you like to never go home? I can make that happen you know. I can make sure you never go home, Bronwin, so you need to start to tell everyone you’re sorry for telling lies about those nice men.’

‘They ain’t nice. They ain’t.’

Dr Berry grabbed hold of Bronwin’s arm and shook her hard, his face red with anger. ‘I’m warning you, Bronwin.’

Bronwin didn’t say anything. She didn’t even know why she was here and all she wanted to do was to go home. She curled up tighter in her sadness as she listened to Dr Berry continue to rant. ‘And you know what’s happened now, don’t you?’

Bronwin shook her head.

‘Now everybody thinks you’re a liar. The police, the courts, even your mum does. That’s why they were found not guilty.’

Hearing the psychiatrist mention her mother, Bronwin sat up, her face scrunched up in a mixture of hurt and anger.

‘No she don’t! She never said that!’

‘Bronwin, I don’t tell lies because I know it’s wrong.’

Rubbing away a tear with the back of her sleeve, Bronwin yelled, ‘You’re a big fat liar.’

Dr Berry slapped Bronwin hard across her face, causing an angry welt to appear on her cheek. Taking his glasses off to wipe them with the corner of his starched white doctor’s coat, Dr Berry didn’t bother to look at Bronwin as he spoke.

‘That’s why she hasn’t been to see you, Bronwin, because she doesn’t like liars. She told me she didn’t want you to come home. No one is ever going to believe a word you say. No one trusts you, Bronwin, which means no one’s ever going to believe you when you tell them what happened in the woods.’

At the word woods, Bronwin covered her ears.

‘It’s no good doing that, Bronwin. The only way to change this is by telling the truth and stopping these silly lies.’

‘But I keep telling you, it ain’t a lie. I want to go home. I want to see me mum and me sister.’

‘Bronwin, I’ve told you this before. Your sister is dead.’ Bronwin immediately began to scream. Her wail was fearful and high pitched; an adult’s cry within a child’s body. The scream resonated through her and began to take possession of her body as it started to shake, convulsing her into a fit. Dr Berry pressed a button and a moment later a white-gowned nurse entered the room.

‘Give her fifty millilitres, nurse.’

The nurse picked up a full syringe from the silver drugs trolley nestling in the corner of the room, then quickly and expertly administrated the powerful drug into Bronwin’s leg. Almost immediately, Bronwin’s eyes began to roll back. Her shoulders began to slump and her mouth gently opened to one side as she lay on the bed in the tiny whitewashed room.

After a couple of minutes, Bronwin’s eyes slowly regained focus and she sat staring ahead at nothing but the blank wall.

Today was her seventh birthday.

In the next room, Bronwin’s mother sat nervously pulling down the grey nylon skirt she’d bought from Roman Road Market the day before. She’d wanted to look presentable and it was only now she was realising that the skirt might be too short. Perhaps she should’ve got the other one, the longer one, but it’d been a fiver more and she’d needed the fiver for the electricity key. Taking off her jacket, she placed it over her knees.

She was nervous. Her hands were sweating and she could feel a prickly heat rash beginning to develop on her chest. She knew what these people were like. Knew how they judged; Christ, she’d been dealing with them since she was a kid herself, and now they had their hands on her daughter.

Week after week she’d called up to see Bronwin, but they’d told her she couldn’t. She’d even turned up a few times, hoping someone would show a bit of compassion, but she’d been turned away, not even being allowed to step foot into the children’s facility. All she’d been told was that social services and the doctors thought it was best for Bronwin to be taken into temporary care. That wasn’t going to stop her though; she was going to get her daughter back and bring her home where she belonged. Today was the first time she was able to see the doctor in charge and, as her nan used to say, she was shitting bricks.

Gazing around the room made her feel even more nervous. There were paintings of men in gilded frames on the wall, looking superior and mocking. It surprised her to see the doctor’s office void of any medical books, but instead filled with trinkets and thank you cards. She jumped as the glass door opened.

‘Hello, I’m Dr Berry, we’ve spoken many times on the phone. Thank you for coming.’

Refusing to take the outstretched hand, Bronwin’s mum thought the doctor looked like he should’ve retired years ago. His white hair and stooped shoulders made her feel as if she was paying a visit to her granddad rather than a child shrink.

‘I’ve been trying to come for a while now, but then you’d already know that, wouldn’t you? What I want to know is when can I take Bronwin home?’

‘Well, that might be a problem. Bronwin doesn’t want to come home. She’s a very troubled little girl.’

Bronwin’s mother flinched. ‘I don’t want to hear about bleedin’ problems mate. I just want to take her home where she belongs. She’s my daughter, not yours, and I don’t believe she don’t want to come home. I want to see her.’

Dr Berry went round to the other side of his desk. He pulled out his chair slowly, staring moodily over his rimless glasses. ‘How do you feel about your other daughter’s death? Kathleen, wasn’t it?’

‘I ain’t here to talk about me other daughter. In fact, I ain’t here to answer any questions at all. Just give me Bronwin so we can get out of here.’

As was his habit and his arrogance, the doctor ignored the interjection and continued to talk. ‘Do you feel responsible for your daughter’s death?’

Bronwin’s mother stared ahead, painful, angry tears about to fall. She didn’t know if it was her imagination or not but she was sure she could see a tiny smirk on Dr Berry’s face as he asked about Kathleen.

She was pleased to hear her voice was steady as she made a concerted effort to stay calm. Her words punctuated the air. ‘I’m not responsible for her death. It wasn’t me who killed her.’

‘But you were the one who let your daughters out. Surely you must hold some sort of guilt?’

Bronwin’s mother blinked away the tears as she felt them burning. She bent forward, holding her stomach, and whispered almost inaudibly as her gaze found the window. ‘Of course I do. Of course I do.’

‘Then let us help you. You do want some help, don’t you?’

Bronwin’s mum nodded, trance-like.

‘I still don’t really know why she’s here.’

Dr Berry’s expression was patronising. ‘I think you do, but if you need reminding again, why, I’ll tell you. Myself and social services thought it was for the best, especially in the light of your past history with children’s services. It’s our job to make sure children are safe from harm. You know Bronwin is still very confused with what happened and who was there that night in the woods. Like I said before, she’s a very troubled little girl. She insists on telling these lies.’

‘Bronwin ain’t a liar. That’s one thing she’s never done is lie. If she’s telling you something then it must be true.’

‘That’s as maybe, but she’s a child and all children lie.’

‘She don’t.’

Dr Berry sighed. ‘Do you want us to help her and at the same time help you?’

‘Of course!’

‘I had another meeting with her social workers and they’re in agreement with me that it’s probably best for all of us, you as well, if Bronwin stays here with us. Permanently.’

Bronwin’s mother stood up. Her body shook with fear and fury. ‘Oh no you don’t. You ain’t going to mess my little girl up.’

‘We won’t be doing that; what we’ll be doing is untangling the mess that has already been put there in her short life.’

‘That ain’t going to happen. You ain’t going to take my daughter.’

‘Of course not. That’s why I’m asking you to sign these papers.’

‘I’m not signing nothing. I want my daughter and I want her now.’

‘I’m sorry, but that won’t be possible. We’ve had an extension of the interim care, which means you can’t take her.’

The shock and hurt on Bronwin’s mum’s face was naked. Dr Berry turned away quickly as the shouting began.

‘You bastards. You fucking bastards.’

‘We’re not doing this to upset you, we’re doing this for Bronwin’s benefit. You’ll be able to get on with your life, knowing Bronwin is getting the help she needs. She’ll thank you in the end, I know she will. You can give her what you didn’t have yourself. You can give her a chance and a start in life.’

‘But I’m her mother. She should be with me.’

‘Yes, but only if it’s right for her – and at the moment, it isn’t right.’

Bronwin’s mother headed for the door, catching Dr Berry raising his eyebrows at her skirt. She pulled it down quickly.

‘Well I’m sorry, but no way. I would never hand my child over to the likes of you. I might not be what you think a good mother should be, and I’m not saying I haven’t got my faults, but I love Bronwin. I loved both my kids.’

Dr Berry’s face was twisted with cruelty. ‘Fight us? Fight me and you’ll lose – and then you’ll never see Bronwin again. Do it this way and you’ll be able to see her. It’s your choice.’

‘You … you can’t do that.’

‘We can and we will. Do you really think the courts will agree to you keeping her after both myself and the social workers give evidence of you being unstable and incapable of giving Bronwin what’s needed?’

‘I love her. Ain’t that enough?’

‘In an ideal world it is, but then we’re not in an ideal world, are we? Can you excuse me one moment?’

Not waiting for any sort of reply, Dr Berry picked up the phone on his desk. He spoke quietly into it. ‘Would you mind coming in now?’

A moment later the glass door opened. The man who walked in didn’t bother to introduce himself. He stood with a frozen frown on his face as Bronwin’s mum stared at him. ‘Who’s he?’

Once more, Dr Berry chose to ignore a question he saw as irrelevant. He walked over to Bronwin’s mum, picking up the papers as he passed his desk, then reached out with the pen that was always kept in his breast coat pocket.

‘Sign them. It’s for the best. If you say you love her, which I believe you do, you’ll listen to me. No one’s the enemy here.’

Bronwin’s mother took in the doctor’s face. Deep entrenched lines circled his eyes and cold small green eyes stared back at her. ‘You’ll let me see Bronwin?’

Dr Berry pushed the pen and papers forward. ‘She’ll be in good hands. There’s nothing to worry about. I promise.’

Taking the papers, Bronwin’s mother grabbed at the pen and hurriedly scrawled her name on the papers. Next, Dr Berry passed the papers to the other man, talking as he did so. ‘We need another signature, you see, so that’s why this gentleman’s here. You’ll get a copy of this for yourself.’

The other man took out his own pen. Bronwin’s mother watched, loathing etched on her face as her eyes traced the flamboyantly written signature.

Dr Berry smiled, his tone overly jovial for the sentiment of the occasion and his clichéd remark inappropriate.

‘Right then, that’s all done and dusted.’

‘Now take me to see my daughter.’

‘You’ve done the right thing.’

‘So why doesn’t it feel like it?’

Staring through the glass pane of the door, Bronwin’s mother wiped away her tears before opening it. Quietly, she walked into the room, feeling the air of hush as she entered. She stared at her daughter. So tiny. So elf-like. So beautiful.

‘Bron. Bron, it’s me.’

Bronwin’s eyes stayed closed.

Dr Berry crept up silently behind her. ‘It’s all right, she’s had some medicine to calm her down. She’s just in a heavy sleep.’

‘Can I wake her up?’

‘It’s best to leave her. She needs all the rest she can get.’

Leaning forward, Bronwin’s mother swept her daughter’s mass of blonde hair away from her forehead. She kissed her head before speaking to her sleeping child. ‘Bron, Mummy’s got to go now. But always remember I love you and I’ll see you soon, and Bron … I’m sorry.’

Turning to the doctor, Bronwin’s mum stood up and went into the pocket of her torn jacket. ‘Can you give her this? It’s her birthday card.’

‘Yes, of course. The nurse will see you out. The social workers will be in touch in the morning to sort the other details out.’

Once Bronwin’s mother had left, Dr Berry took a quick glance at the card before throwing it into the bin in the corner. Deep in thought, he stood observing Bronwin as she began to stir.

The door opened, jarring him from his thoughts. He smiled at the entering visitor and reaching out his hand with a welcoming greeting. ‘Thanks for signing those papers, by the way. I thought for a moment the mother was going to be difficult and start making a noise about her parental rights. I’ll just wake her up for you.’

Walking across to Bronwin, Dr Berry gently nudged her. He spoke quietly. ‘Bronwin? Bronwin? Hey birthday girl, you’ve got a visitor. Someone’s here to see you.’

Bronwin slowly opened her eyes before rubbing them gently. She sat up, then screamed. It was the man from the woods with the black shiny shoes.

‘She’s all yours, come and find me when you’ve finished. Oh, and have fun.’ Dr Berry chuckled unpleasantly, tapping the man on his back as he left the room, leaving him sitting on Bronwin’s bed as he began to unbutton his shirt.

Nine years later

The bed was hard and the chair was too. Sparse and unwelcoming. And Bronwin didn’t know why she couldn’t go home, instead of having to stay in a house where she didn’t want to be and didn’t know anyone. It was the same recurring thought she’d had each time they sent her somewhere new.

She’d been in more care and foster homes than she could possibly remember and over time she’d developed a sixth sense. Knowing when people really wanted her or when all they really wanted was the few hundred quid caring allowance they got for taking in the likes of her.

How long had it been now? Eight years, nine even. Nine years of going from one home to another.

She no longer wanted to be, or to feel like, the unwanted teenager. The problem child. Hard to place. Hard to love. She didn’t want to become bitter; hardened to life before she’d reached eighteen.

She was determined to change it. To take control. And as Bronwin stared out of the window at the rainy night she made a decision. The time was right. She was old enough not to have to listen to a bunch of jumped-up social workers telling her what to do. All they really did anyway was to find her a roof over her head – the rest of it was left to her.

Bronwin stuffed her clothes and the bedraggled Mr Hinkles, her childhood teddy bear, back into her bag, then opened the window. She felt the chill of the evening air and the spray of the rain on her face, blown in by the wind. Making sure no one could hear her, Bronwin shuffled onto the ledge. It wasn’t so far down. Seven feet perhaps, maybe eight. Eight feet to freedom.

After a count of three in her head and then another one of five, Bronwin jumped, hitting the ground hard. She rolled on the grass and felt a sharp pain in her ankle, shooting pains up the outside of her leg, but she didn’t care. All that mattered to her was that she was out. Out of the care system that had never cared for her and out of the system that had taken away her mother, the one person she’d cared about.

Getting up from the wet ground, Bronwin ignored the pain. She quickly picked up her bag, making sure no one in the house had seen her. The rain hit down hard on her but instead of it feeling cold, it felt warm, invigorating. She was free. She was finally free. Today was her sixteenth birthday.