Читать книгу Getting Jesus Right: How Muslims Get Jesus and Islam Wrong - James A Beverley - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

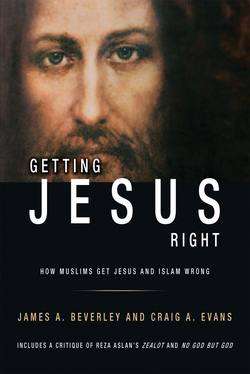

Oldest Synoptic Gospels Papyri

ОглавлениеThat the teaching of Jesus circulated and was known well before the Gospels were written is demonstrated by the appearance of his teaching and aspects of his life and death in earlier writings, such as the letters of Paul, the earliest of which were penned in the late 40s. Paul often alludes to Jesus’ teaching, though sometimes he explicitly cites a “word” from the “Lord.” We see an example of the latter when Paul charges the people in the church at Corinth not to seek divorce: “To the married I give charge, not I but the Lord, that the wife should not separate from her husband…and that the husband should not divorce his wife” (1 Cor 7:10–11). It is the Lord, Paul says, who has given command that divorce should be avoided. Paul has appealed to Jesus’ teaching, which he gave in response to a question put to him concerning the divorce regulations in the Law of Moses (Matt 19:3–9; Mark 10:2–9). After quoting parts of Genesis 1:27 (“male and female he created them”) and 2:24 (“they become one flesh”), Jesus asserts, “What therefore God has joined together, let not man put asunder” (Mark 10:6–9).

Another obvious Jesus tradition in one of Paul’s letters is the citation of the Words of Institution, that is, the words Jesus spoke at the Last Supper (Matt 26:26–29 = Mark 14:22–25 = Luke 22:17–20). Paul finds it necessary to instruct the church at Corinth, reminding them of what Jesus did and said on that solemn occasion:

For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, “This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way also the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” (1 Cor 11:23–25)

Paul’s wording matches the form of the story in Luke very closely, which probably should not occasion surprise, for Luke the physician traveled with Paul on some of his missionary journeys.9

Of even greater significance is the appearance in Paul’s letters of allusions to Jesus’ teaching. When the apostle commands, “Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse them” (Rom 12:14), he has echoed the words of Jesus: “Love your enemies…bless those who curse you” (Luke 6:27–28); “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matt 5:44). When Paul speaks of mountain-moving faith, saying “if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains” (1 Cor 13:2), he has alluded to Jesus’ famous teaching: “if you have faith…you will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move” (Matt 17:20). When Paul warns the Christians of Thessalonica that “the day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night” (1 Thess 5:2), he has alluded to the warning Jesus gave his disciples: “if the householder had known in what part of the night the thief was coming, he would have watched” (Matt 24:43). Paul’s admonition that the Thessalonian Christians “be at peace among” themselves (1 Thess 5:13) echoes Jesus’ word to his disciples that they “be at peace with one another” (Mark 9:50).10

Paul is not the only New Testament writer to show familiarity with the teaching and stories of Jesus; the letter of James is filled with allusions to the teaching of Jesus.11 There are important allusions in Hebrews and 1 and 2 Peter also. All of this shows that the teaching of Jesus was in circulation long before the Gospels were written, and even when the three early Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) were written, many of Jesus’ original followers were still living and active in the Church.

What all of this means is that the four New Testament Gospels were written early enough to contain accurate data relating to the teaching and activities of Jesus. Three of the four Gospels were written within the lifespan of many of Jesus’ original disciples. The Gospels were not written hundreds of years after the ministry of Jesus and the birth of the Church; they were written toward the end of the first generation. And the New Testament Gospels are not the oldest documents in the New Testament. Older writings, such as the letters of Paul (and probably James as well), contain quotations, allusions and echoes of the same material.

But what about the Jesus stories and teachings in the Qur’an that are distinctive to the Qur’an? Should we accept these materials as authentic and therefore historically reliable? And if the Qur’an’s version of the Jesus tradition contradicts the tradition of the New Testament Gospels, should the Qur’an’s version be preferred?

The first and most obvious problem with the Qur’an as a source for new stories and teachings that supposedly go back to Jesus is that the Qur’an was written 600 years after the ministry of Jesus. We don’t doubt that the Qur’an might give us some authentic thoughts and teachings of Muhammad. Several friends and supporters who had heard his teaching were still living after he died and were able to assemble his teaching and write out the Qur’an. The Qur’an was written in its final form only about one generation after the death of Muhammad (though the process of editing may have continued for another generation or two), just as the New Testament writings were written only about one generation after the death and resurrection of Jesus.12

But does this mean that the Qur’an is a reliable source for the historical Jesus, especially if in places it contradicts what is said in the first-century Christian Gospels? No, it does not. The problem is that the Qur’an was written more than half a millennium after the time of Jesus, some 550 years after the writing of the New Testament Gospels. No properly trained historian will opt for a source that that was written more than five hundred years after several older written sources.

We face the same problem with distinctive Jesus traditions in the rabbinic literature. Jesus appears in the Tosefta, which cannot be dated earlier than AD 300, or about 225 years after the New Testament Gospels were written. More traditions about Jesus appear in the two recensions of the Talmud. The Palestinian recension dates to about 450 AD, while the Babylonian dates to about AD 550. Historians and serious scholars find this material colorful, even entertaining, but they view it with suspicion as regards trustworthiness about Jesus. And why shouldn’t they? These compendia of Jewish law and lore were compiled hundreds of years after the time of Jesus and the New Testament Gospels. They are almost as far removed in time as the Qur’an. Historians make little use of rabbinic literature as historical sources in writing about the historical Jesus.

As we will see in a later chapter, almost all of the Qur’an’s distinctive Jesus tradition seems to have been derived from later times and places, such as Syria in the second and third centuries. The Jesus of the Qur’an seems to be very much colored by the type of asceticism that was taught in second- and third-century Syrian Christian circles, such as the Encratites. Some of the sources on which Muhammad relied are quite dubious, such as the Infancy Gospel stories (where, for example, Jesus gives life to birds made of mud) or the strange idea of Basilides (who said it was not Jesus who was crucified but some poor fellow who looked like Jesus). Some of Jesus’ alleged pronouncements in the Qur’an (e.g., where Jesus denies his divinity) reflect the debates and polemics that were part of Muhammad’s context in Arabia in the late sixth and early seventh centuries, not the context of Jesus and his contemporaries in first-century Israel. Indeed, the Jesus of the Qur’an is largely an imagination of a mid-seventh century religious community.13

For all of these reasons, very, very few historians make use of the Qur’an as a source for finding out what the historical Jesus said and did. We suspect this is why Muslim writer Reza Aslan in his recent book on Jesus makes no use of the Qur’an and early Islamic tradition.14 Having had some graduate education in a setting where he would have learned something about the work involved in doing historical Jesus research, Aslan would know that the Qur’an and rabbinic literature are not useful sources for such a purpose.

Although their assessments may differ, historians agree that our best sources for understanding what Jesus really said and did are the New Testament Gospels and some other early Christian and non-Christian writings. In the balance of the present chapter, we address three important questions that must be faced in the study of the New Testament Gospels. The first question asks if the Gospels are based on eyewitness testimony, the second asks if the ancient manuscripts of the Gospels are reliable, and the third question asks if the Gospel manuscript record compares to that of the great classics from late antiquity.