Читать книгу Land Of The Leal - James Barke - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

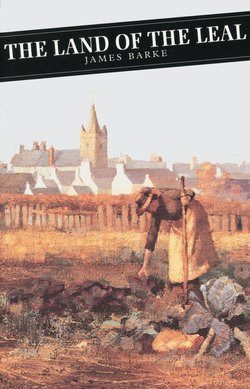

GALLOWAY GLOAMING

ОглавлениеTom Gibson weeded and hoed in his garden till dusk began to settle on the land. Then he lit his pipe and leaned his arms on the garden wall close to a clump of gooseberry bushes. From the garden wall the land fell away towards the heughs of the coast and towards Craigdaroch Bay. He could smoke in peace for as yet the midges were not out in their plaguing myriads.

Tom Gibson, though he could rarely allow himself moments of inactivity, could, at the end of such a day of fruitful toil, lean on his garden dyke and meditate. His mind was extraordinarily calm. He had never known, and it seemed he would never know, excitement. Excitement was a sign of weakness: of instability. But there was no weakness or instability about him. He was rock-sure of himself: the earth was beneath his feet. He could afford to meditate in his garden – even if it was a kitchen garden. He would have been ill-at-ease in a garden where good soil and good labour was wasted on the cultivation of flowers.

He puffed slowly and deliberately at his pipe and gazed almost dreamingly over the dusk gathering fields towards the sea. He found the world good. But even as he gazed he was thinking how to-morrow he would vist the dominie at Dunmore. The dominie was a runt: a mere invoice of a man. His audacity in inflicting injury on his child was in the nature of an aberration: but an aberration that would not be allowed to go unchecked.

But there was no hatred in Tom Gibson’s heart: no petty desire to revenge himself on the dominie. He would merely teach him a much-needed lesson: administer effective censure. Not to do so would be to fail in his duty.

And yet in his meditation he found pleasure. There was much satisfaction in being strong and resolute and determined. The working of his iron will brought him a sweet feeling of power. Once doubt and indecision entered, this deep and elemental satisfaction fled.

He was in the magnificent prime of his life. He worked on the land as a Beethoven or a Michael Angelo worked at his art. He was a master-labourer, consummate in his skill, indefatigable in his strength. He could not envisage a day when his muscles would wither and his strength decline and the edge of his cunning dull.

The swallows had gone from the sky: a solitary bat squeaked above the steading of Craigdaroch: a large white moth fluttered among the rank grass and weeds close to the dyke-side. The cattle turned their way from the burn and began to work up through the field. In the stillness could be heard their rasping of the dew-wet grass; the restless movement of a sexually stimulated heifer; the heavy anticipatory breathing of the almost satiated bull as he nosed his way with uplifted muzzle through the herd. The bull, like Tom Gibson, was sure and deliberate: overpowering in its masculine domination.

The grieve of Craigdaroch was alive even in his brooding meditation to every subtle harmony of the night. But he had overstayed himself. He withdrew his pipe from his mouth, tapped the ash gently on his palm, and taking a deep breath of the night air (for a sigh would have been foreign to his nature) he moved towards the house that had already merged with the night: gathered in upon itself in sleep.