Читать книгу Land Of The Leal - James Barke - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

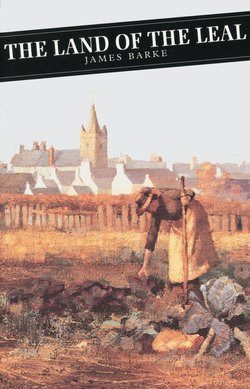

LAND OF HOPE AND HARDSHIP

ОглавлениеIt was cattle show day: all roads led to Stranraer. The show day was the one holiday of the year. Every one who could be spared from the farms was allowed to take part in the festival. And it was a festival. Brothers and sisters and friends met on that day and perhaps did not meet again for another year.

Carts lumbered out of the steadings as soon as the cows had been milked and the milk vatted for cheese. Every one was light-hearted – more so that the day was pleasant and warm. There was laughter and bantering and singing: here and there the music of a melodeon. For a year they had laboured day in and day out: now there was a brief spell of freedom, communal freedom.

For the lovers – and every eligible youth and maid in Galloway were lovers – there was the prospect of a meal together and the buying of favours. For the women there was the prospect of shopping: for the men a social round of drinks. For many there was the anticipation of being photographed: it was the latest craze. The two photographers in the town looked forward to an endless procession of sitters.

David Ramsay was full of high eager spirit. He had never been to Stranraer though he had often gazed on it from a distance, his eye picking out the thin ship masts in the harbour. Maybe to-day there would be a ship and he would manage to steal a word with the skipper or the mate.

But he was disappointed: there were only a couple of colliers in the harbour that day. But his disappointment was soon forgotten: to-day everything was an adventure.,

As they approached Stranraer the road became congested. David had never seen so many carts, gigs, phaetons, traps and conveyances. Every kind of vehicle seemed to have been utilised for the journey.

There were three carts from Achgammie, four behind them from Cortorfin and at least a dozen ahead of them from the farms of Leswalt. As the carts slowed down and trailed each other there were shouts of salutaton and recognition and the bandying and bantering of crude humour. But sometimes the remarks were pointed and barbed with malice, as when a man from Cortorfin commented wittily on the crookedness of Achgammie’s furrows. The Achgammie folks could not laugh for the MacMeechan sons were present, girning sourly.

The cattle show was not of much interest to David Ramsay: he was not intensely interested in prize cattle nor in a parade of horse nor yet in cheese or scones. He was captivated by the mass of humanity in motion and the babble of voices and the sound of strange accents from Stoneykirk and Kirkmaiden, Glenluce and the Stewartry. He was greatly interested in the town itself with its narrow cobbled streets and the fascination of its shops.

About twelve o’clock he asked his way to Harbour Street. He walked down the street till be found the shop, MacGeorge – Baker, where his father had said he would meet him. His father was not yet forward when he arrived but while he was waiting outside, his sister Agnes came along.

‘Are you waiting on my father, Dave?’

‘Aye: he said he would meet me here, Aggie. Are you waiting for him yourself?’

‘He said he would see me here too. He’s sailing down with Adam and Samuel.’

‘Maybe we should go down to the harbour?’

‘No: they’ll be in by now. But you’d better wait for you might never find them in the crowd … How do you like Stranraer?’

‘Oh, it’s a fine place. I never thought there would be so many shops.’

‘Are you getting your photograph taken the day?’

‘Me? What would I do getting my photograph taken – are you?’

‘Aye. There’s three of us going in the afternoon. It’s going to cost 2/6d …’

Andrew Ramsay came up the street at an unusually brisk pace. He had had a dram or two but he was by no means drunk.

‘You’re here, the pair o’ ye? Well… and what do you think o’ Stranraer, Dave?’

‘It’s a big place …’

‘Aye: it’s a’ that: and I don’t remember it being as crowded on a show day. But you’ll be hungry? Come on in and we’ll have a bowl o’ soup and a meat pie – if the wild folk o’ Kirkmaiden havena eaten them all up. Come on, Aggie my lass – you’re looking well …’

The eating-house was crowded and stuffy: the odour of hot fat and grease from the kitchen was almost overpowering. The chatter and laughter was like the rumble of distant thunder. They had difficulty in getting a place at a table together. But folks were only too willing to help each other. The atmosphere was permeated with warmheartedness and good nature.

‘Come awa’, Andra: here’s a seat for you – oh, damn, but the weans will hae to get a seat tae. Move up there, Tam: you’re taking up more room wi’ your muckle elbows than you are wi’ your backside – damn it, man, the yae dowp on the bench should content ye. Grand day for the sail up the Loch, Andra! Man, I was sorry to hear about the Reverend Mr. Ross – God Almighty, wasn’t yon a storm! We could dae wi’ you doon at the Bangan dykes, Andra.’

Andrew Ramsay laughed and made reply here and there. David did not know that his father was so well known. He felt shy for he had never been in an eating-house before. An extremely red-faced perspiring lass brought them three steaming bowls of the thickest broth David had ever tasted.

Andrew Ramsay looked happier than he had done in years. He was happy for many reasons: but mostly he was happy because his boy was happy. He knew David had never tasted a meat pasty and it gave him pleasure to see David enjoying it with such evident relish. He would have liked, had there been time, to take him round the town and the harbour and show him all the places of interest. But there was no time for this. He had too many people to see and too many people to drink with. There was always the chance that a farmer, feeling in a generous mood, might drive a bargain with him to repair his dykes.

Sitting amidst that coarse warm humour, David Ramsay became almost reconciled to the prospect of working on the land. After all he was young: life was only beginning to open and reveal itself to him – an adult life that had contact with the town. He felt this was his initiation into the adult world. His sister Agnes looked happier than he had ever seen her: she seemed to have become a woman since she had gone into service.

What David could not appreciate was that the cattle show was the grand gala day for most of the folks up and down the Rhinns of Galloway. There was only one such day in the whole year. The liberation of spirit after a year’s bondage was such that almost every barrier to happiness was broken down. There was freedom and a limited supply of money and time in which to eat, drink and be merry: there was freedom to meet and discourse at will on any topic or to gossip to the heart’s content: there was freedom to get measured for a suit of clothes, purchase a pair of boots or choose a new bonnet or select a yard of coloured ribbon. There was freedom to be one’s self for part of a day and to revel in that freedom.

But that freedom came to an end with the approach of milking time. Those who had come farthest had their carts yoked and were already trekking from the town. David was surprised at the large number of men who were incapably drunk and who had to be assisted into the conveyances by men only slightly less incapable. Even young boys in their early teens swayed and staggered under their unaccustomed load of liquor. And many felt sick and sorry for themselves – having parted with their soup and pie in a painful drunken vomit. Women raged and nagged at their husbands. But most of the husbands just smiled and swore back at them: to hell! it was the cattle show – even if they had never seen the bloody thing.

But for all the drink that had been consumed there was little unpleasantness and most of the parties went home in great good spirits to the accompaniment of much drunken singing of Bonnie Gallowa’.

Bonnie Galloway, indeed! Little did they see of its splendour and beauty. They knew of its confined and restricted and much-husbanded acres. But the excess of their toil on its individual fields made the land dearer to them. Despite all the landlords and petty farmers it was their land: it was their home. No one had more right to sing its beauty and praise. If there was sadness in their song, that was the way of all songs of a land that was toiled and worked over in blood and tears. There had been too much blood and tears!

Too soon the hands would grasp the plough-handles, the stock of the flail, the lugs of the milking pails, the obstinate teats of the calved heifer, the rake of the cheese vat, the neck of the corn sacks … But, for the moment, the joy of the liberation of laughter and song.

Bonnie, bonnie Gallowa’: and those spots in the Rhinns dearest above all.

Allandoo, Achgammie, Achneel, Auchnotteroch, Auchteralinachan, Auchtrimakain, Ardwell Bay, Auchness, Auchleach, Auchneight;

Ballscalloch, Barnhills, Barnscarroch, Bughtpark, Balwhinie, Barbeth, Balgown, Barscarrow, Barncorkerie, Barnchalloch;

Cairnbrook, Cairnhandy, Cairngarroch, Cairnwellan, Cairnbowie, Craigmodie, Craigencrosh, Craigcaffey, Corsewell, Carrickadoyn, Clachan Heughs, Colfin, Culchintie, Currochtrie, Clachanmore, Culgroat, Clayshant, Clanyard, Crummag, Cardrain, Cardoyne, Chapel Rossan, Clipper Drigan Well;

Dunanrea, Drummore, Dumbreddan, Dinduff, Dindinnie, Dinvin, Dunman, Damnaglaur, Drumantrae, Dundream, Dalvadie, Drumfad, Dundribban;

Enoch;

Fintlock;

Genoch, Glengyre, Glengitter, Glenstockaddle, Grenan, Garrochtrie, Glenoch, Gachvie Moss, Gladenoch;

High Mark, High Maggarty;

Knocknain, Knockneen, Knockcoid, Knockieausk, Knockmudloch, Kirkminnoch, Kirkbride, Kirklaughlane, Kirkmagill, Kirkmadrine, Kildonan, Killumpha;

Lochans, Lagvag, Lagganmore;

Mull of Logan, Mulldaddie, Marslaugh, Myroch, Muntloch, Meikle Gladnoch;

Nick o’ Kindrum;

Pirnminnoch, Portlogan, Portayew, Portpatrick, Por-tencalzie, Portcarvillan, Portnaighton, Portencorkerie;

Ringvinachan, Ringuinea;

Slunkrainey, Slouchnawen, Sandell Bay, Sandhead;

Tarbet, Tandoo, Terally;

West Freuch …

In the moment of physical and spiritual freedom the agricultural labourers of the Rhinns of Galloway recalled all that was pleasant, all that was sweet in their lives.

Many an older man told with pride how he had been reared on this farm or married on that.

It was remarkable, considering the hardness of their labour and the poverty of their days, how strong and affectionate was their love for the land, that gave them birth. At such a moment they did not think of cruel and greedy farmers nor of avaricious landlords. They thought and spoke and sang of the land as the land of their fathers, the land of their birth, the land that was their immemorial heritage.

David Ramsay was keenly sensitive to this aspect of the day’s outing: he responded to it deeply. He was profoundly attached to the parish of Kirkcolm, to that part of it around the Suie and Achgammie. But he could not think of the coarse grazing land the heughs and the shore in terms of John MacMeechan or Sir Thomas MacCready. It was of no consequence to whom the land belonged: it existed; and spiritually it was his to enjoy. He had enjoyed it and it had moulded and influenced his spirit more than he knew.

And to the day of his death the surge and sough of the sea breaking on the Loch Ryan heughs and the cry of the whaups on the high lands of Achgammie were to vibrate in his memory.