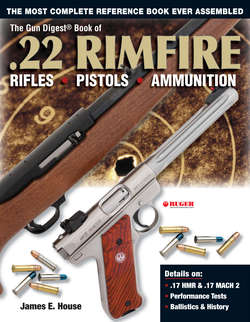

Читать книгу The Gun Digest Book of .22 Rimfire - James E. House - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1 DEVELOPMENT OF RIMFIRE AMMUNITION

As you look at the rimfire section of the ammunition counter in a sporting goods store you will see stacks of boxes labeled 22 Long Rifle (LR), 22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (WMR), and 17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire (HMR). If the store has a comprehensive line of ammunition, you may also see boxes of the new 17 Mach 2, 22 Short, 22 Long or perhaps those dinosaurs known as the 22 CB Short and 22 CB Long that live on for some reason. It is possible that you may also see a box or two of 22 Winchester Rim Fire (WRF), a cartridge that was introduced in 1890 along with the Winchester Model 90 pump rifle that was chambered for the cartridge. As this is being written, another 17-caliber cartridge or two are being marketed or are under development.

The frame of the Smith & Wesson opened at the bottom and was hinged at the top.

The Smith & Wesson No. 1 First Issue was the first revolver chambered for the 22 Short black powder cartridge. Shown here is a No. 1, Second Issue model.

Pinfire cartridges were produced in several calibers including shotgun rounds.

If this list of approximately 10 cartridges makes it seem like there are many choices in rimfire calibers, look again. The 22 Short, Long, Long Rifle and the two CB rounds are all used in the 22 LR chamber. The 22 WMR is a separate caliber as are the 17 HMR and 17 Mach 2. We can ignore the 22 WRF for the moment. What we have is really a short list of rimfire cartridges most of which can be used in firearms of one caliber, but as we shall see it has not always been so. In this chapter, we will provide a brief history of rimfire ammunition and a description of some of the most significant obsolete and current rimfire cartridges.

Cartridge Development

One should not lose sight of the fact that developments in different areas of science and technology are interrelated. For example, it would not be possible to build a long-range rocket without developments in rocket fuel (which is a problem in chemical science). It was not possible to produce the atomic bomb until methods of enriching uranium were developed. The high performance of cartridges today is in great measure the result of improvements in propellants and metallurgy. Some of the basic principles involved in cartridge performance will be described in Chapter 7.

The four approaches to firing metallic cartridges are illustrated here. The cartridges illustrate (left to right) teatfire, pinfire, rimfire, and centerfire types.

Teat fire cartridges were developed in the 1800s before rim fire cartridges were introduced.

A cartridge consists of a primer, propellant, projectile, and a case for these components. In order to ignite a propellant, some substance that explodes is needed. The cause of the explosion is actually percussion (crushing) that is the result of a spring-loaded striker (hammer or firing pin) changing positions at the time of firing. In order to have shot-to-shot uniformity (which results in accuracy), it is necessary to have the same amount of explosive (primer) ignited in the same way for each shot and have the same amount of propellant in each cartridge.

Early developments in muzzle-loading firearms included the flintlock and the caplock, which used a percussion cap. In the flintlock, the primer consisted of a small amount of fast-burning black powder of fine granulation (FFFFg) that was ignited by the sparks produced when a piece of flint struck a piece of steel known as the frizzen. The priming charge was held in the flash pan, which had a hole that led downward into the barrel where the main propellant charge was held. The gas resulting from the burning powder in the main charge provided the driving force to move the bullet down the bore.

As firearm technology developed, so did the chemistry of explosives. It was discovered that mercury fulminate exploded violently when it was struck. Therefore, percussion caps were produced which consisted of a small amount of mercury fulminate contained in a small copper cup that fitted over a hollow nipple. When the hammer fell and struck the cap, the mercury fulminate in the percussion cap exploded which ignited the powder charge as fire was directed from the primer into the barrel breech. The percussion cap was introduced in the early 1800s, and its use in muzzle loading rifles continues to the present time.

Caplock rifles of yesterday and today are relatively reliable devices. This author has fired many rounds through his muzzle loading rifles with only a few instances of misfiring or delayed firing (known as a hang fire). Loading a caplock rifle is a slow process because the powder charge must be measured and poured into the barrel and a projectile loaded on top of the charge. The process is slightly faster if the projectile is a “bullet” rather than a lead ball that is used with a lubricated cloth patch. New developments in muzzle loading make use of propellant that is compressed into pellets of known weight. One or more of these pellets can be dropped down the barrel and projectile loaded on this charge. It became apparent that producing a single unit containing the primer, propellant, and projectile that could be loaded in one operation would be a great convenience. That is exactly the impetus that led to the development of so-called metallic cartridges. However, there still remained the problem of where to place the primer in the cartridge and how to cause it to explode reliably to ignite the powder charge. Attempts to solve that problem led to several early designs in metallic cartridge ammunition.

Black powder had been in general use in muzzle loading firearms for many years so it was the propellant utilized in early metallic cartridges. Black powder consists of a mixture of potassium nitrate (saltpeter), charcoal (carbon), and sulfur in the approximate percentages 75, 15, and 10, respectively. Burning rate of the propellant, which is designated by an “F” system, is controlled by the particle size. A granulation known as FFFFg (very fine, often referred to as “4F”) is a very fast-burning form while a coarse granulation designated as Fg is comparatively slow burning. Black powder used most often in rifles is FFg (medium) while FFFg (fine) is used in handguns or rifles of small caliber.

The 41 Swiss (left) and 22 Short (right) illustrate the range of cartridges that were eventually produced in rimfire calibers.

One of the early designs for a self-contained cartridge is known as the pinfire, and it dates from about 1830 when Monsieur Casimir Le Facheux invented it in Paris. The cartridge contained a bullet, propellant (black powder), and a primer. However, the blow of the hammer was transmitted to the primer by means of a pin that stuck out of the side of the case at the rear. This meant that the cartridge had to be oriented in the chamber in such a way that the hammer would strike the pin to push it into the case to crush the primer. Although placing the cartridges in the firearm in the correct orientation made loading slow by today’s standards, it was still rapid compared to loading a muzzle-loader. With pinfire cartridges, there was also the possibility that the protruding pin could be struck accidentally which could force it into the case causing the cartridge to fire. From the standpoint of safety, the pinfire left a lot to be desired. However, cartridges of this type were fairly popular in Europe and some shotguns employed this type of cartridge.

Another cartridge design consisted of a closed tube that contained the bullet and propellant with the primer being contained in a small protruding portion at the rear end of the tube. This type of cartridge, known as the Moore teat fire, was loaded into the front of the cylinder of a revolver with the teat at the rear where it could be struck by the hammer. The front end of the cartridge was flared to form a retaining flange that fit against the front of the cylinder. Cartridges of this design were produced in the mid-1800s. Because the protrusion that held the primer was located in the center of the cartridge head, it was actually a center fire design rather than a true rim fire.

Each of the early cartridge designs described above contained a primer that was sensitive to shock. Subsequent designs would also rely on shock or percussion to cause the primer to explode, but the primer would be located differently in the cartridge. In 1845, a man named Louis N. Flobert in France loaded a round ball in a percussion cap and produced a small cartridge known as the 22 caliber BB (bulleted breech) cap. Power was the result of the primer since no powder was used. Some American versions of this cartridge employed a conical bullet (hence these were known as CB caps) that was loaded over a small powder charge. In 1851 at an exhibition in London, Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson became convinced that this cartridge design could be refined.

The rimfire cartridge was developed by producing a cartridge case with a flange or rim of larger diameter than the body by folding the rear of the case over on itself. The rim was hollow and allowed the priming mixture to be contained within it. The priming mixture was placed in the case while wet and spinning the case caused the mixture to fill the hollow rim. When the primer was dried, it then became sensitive to shock. Crushing the rim by a forward blow of the firing pin caused the primer contained within it to explode which in turn ignited the powder charge.

A short, self-contained 22 caliber cartridge called the Number One Cartridge (essentially identical to the 22 Short of today except for primer and propellant) was introduced in 1854 by Smith & Wesson for use in a small revolver. The revolver was designated as the Smith & Wesson Model 1 First Issue produced from 1857 to 1860. It was followed by the Model 1 Second Issue that was produced from 1860 to 1868 and the Third Issue from 1868-1881. All issues of the Model 1 had a hinge that connected the barrel to the top of the frame at the front end. It was opened by means of a latch at the bottom of the front edge of the frame that allowed the barrel to be tipped up so that the cylinder could be removed for loading and unloading. The cartridge employed a 29-grain bullet that was propelled by 3 to 4 grains of black powder contained in a case that was slightly longer than that of the BB cap. A patent was granted on August 8, 1854 for the rimfire cartridge that was the precursor of the 22 Short. While certainly no powerhouse, the 22 Short has been used as a target load for many years in firearms designed specifically for that cartridge. As strange as it may seem, the 22 Short was originally viewed as a self-defense load! In modern times, small semiautomatic pistols chambered for the 22 Short have been produced for concealed carry and self-defense. The 29-grain bullet from the 22 Short high-velocity load has a velocity of approximately 1,095 ft/sec while the 27-grain hollow-point bullet has a velocity that is a slightly higher.

Introduced in 1887, the 22 Long Rifle (LR) is by far the most popular rimfire cartridge. However, another 22 rimfire cartridge appeared in the 30-year interval between the introduction of the Short and the Long Rifle cartridges. That cartridge, the 22 Long, was introduced in 1871 and made use of a 29-grain bullet propelled by a charge of 5 grains of black powder. Like other 22 rimfires, it eventually became loaded with smokeless powder. The current 22 Long high-velocity cartridge produced by CCI has an advertised muzzle velocity of 1,215 ft/sec, which is about 100 ft/sec higher than the 22 Short. Any difference in power is more imagined than real, and there is no logical reason for the 22 Long to survive. Most of the ammunition companies have ceased production of the 22 Long.

When we come to the 22 LR we arrive at a cartridge that is the most popular and widely used metallic cartridge that exists. It is used throughout the world for recreation, competition, and hunting. The original load consisted of a 40-grain bullet and a 5-grain charge of black powder. Ammunition in 22 LR caliber is loaded in many parts of the world and in some instances to the highest level of technical perfection. The accuracy capability built into a competition rifle chambered for the 22 LR is matched by several types of ammunition that are specifically designed for competition at the highest level. Such ammunition is a far cry from the old black powder loads with corrosive priming that appeared in the 1880s. In later chapters, some of the characteristics of the modern “high-velocity” 22 LR loads will be described. The 22 LR uses a bullet of 0.223 inch diameter that has a short section that is smaller in diameter (the heel) that fits inside the case. The lubricated portion of the bullet is outside the case.

While the target shooter has special ammunition available, the hunter of small game and pests has not been left out. The 22 LR high-speed solid uses a 40-grain bullet that has a muzzle velocity of approximately 1,235 ft/sec while the 36- to 38-grain hollow-points are about 40 to 50 ft/sec faster. Other specialty loads will be described elsewhere in this chapter and in several later chapters. The 22 LR is in many ways the most useful cartridge in existence. A rifle or handgun chambered for this round can be used for many purposes.

22 Winchester Rim Fire (WRF)

In 1890, Winchester introduced a pump-action rifle that is quite possibly the most famous 22 pump rifle ever produced. Designated as the Model 1890 (also known as the Model 90 and some rifles are so marked), the rifle chambered either the 22 Short or a new rimfire cartridge known as the 22 Winchester Rim Fire (WRF) or Winchester Special. The 45-grain flat-point bullet was offered in several loads, some of which gave a velocity as high as 1,400 ft/sec. The original load consisted of 7.5 grains of black powder and it had a muzzle velocity of 1,100 to 1,200 ft/sec. Remington used essentially the same case loaded with a round-nose bullet as the 22 Remington Special. The 22 WRF was popular for many years, but because it offered little advantage over the 22 LR, its popularity declined as the 22 LR became more highly developed.

The 22 WRF (right) is a shorter cartridge than the 22 WMR (left) but has almost identical case dimensions except for length.

The 22 WRF case is larger in diameter than that of the 22 LR. As a result, a bullet of 0.224” diameter fits inside the case mouth without having a section of smaller diameter at the base. This is also the situation with the 22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (WMR) which has almost identical dimensions as the 22 WRF except for length. Therefore, the 22 WRF cartridges can be fired in rifles chambered for the 22 WMR, and they provide a lower-powered (if not lower priced) alternative to the magnum round. In my bolt-action Ruger 77/22M, the CCI 22 WRF ammunition delivers excellent accuracy as will be described in Chapter 15.

Other Early Rimfire Cartridges

Although current rimfire cartridges are all 22 or 17 caliber, many of the rimfire cartridges of historical significance were of larger caliber. One of the most important rimfire developments was the 44 Henry cartridge developed by B. Tyler Henry. It has the distinction of being the chambering for the first successful lever-action rifle. Imagine the effect of a few Union soldiers firing Henry lever-action rifles, which had tubular magazines that held 15 cartridges, on the Confederate soldiers who were using singleshot muzzle-loading rifles! Ballistics of the 44 Henry were not impressive by today’s standards (a 210-grain lead bullet propelled by a charge of 28 grains of black powder to give a velocity of 1,150 ft/sec), but the importance of rapid, sustained fire in military operations is obvious. The 44 Henry cartridge was in production from 1860 to 1934. Another large caliber rimfire cartridge used in the Civil War was the 56 Spencer. Incidentally, the Henry lever-action was produced from 1860-1866 and was no doubt a driving force which led to the development of the Winchester 73 which used the center fire 44-40 cartridge.

Several other rimfire cartridges were developed about the same time as the 44 Henry. As is now the case with 22 caliber cartridges having different lengths, larger caliber “short” and “long” rimfire cartridges were common in the latter half of the 1800s. Examples include the 30 Short and Long; the 32 Extra Short, Short, and Long; the 38 Extra Short, Short, and Long; and the 41 Short and Long among others. Revolvers were often designed with cylinders to accept the shorter cartridges while the extra long types were most often used in singleshot rifles. They were, of course, loaded with black powder. Although there is no need to review the development of all of these cartridges individually, it is necessary to mention several of them in order to trace the evolution of the rimfire cartridge design. It is interesting to note that of the approximately 75 rimfire cartridges that existed in the late 1800s, only about 10 remained in production after WW II.

Two cartridges that were developed somewhat later were the 25 Stevens Short and 25 Stevens Long (sometimes referred to as simply the 25 Stevens) that were introduced around 1900. These cartridges were produced until 1942, and they were popular in rifles like the Stevens single-shot models. Firing a 65- to 67-grain bullet that was driven at approximately 1,200 ft/sec by a charge of 11 grains of black powder, the 25 Stevens had a good reputation as a small game load. Compared to any of the 22 caliber rimfires, the larger diameter, heavier bullet of the 25 Stevens, which had a muzzle energy of approximately 208 ft lbs, dispatched many species more dependably. It would still be a useful cartridge, especially in a modern loading that would improve the ballistics.

It is easy to forget that rimfire cartridges were produced in shorter lengths for use in revolvers and longer versions for rifles in many calibers.

Note how the current 22 Short and Long Rifle have parallels in the 25 Short and Long cartridges of a century ago.

Propellants and Primers

As the quest for better ammunition continued, it was recognized that black powder left a residue that attracted moisture and led to corrosion. Barrel life of the firearm was nowhere near as long as it is today. In the late 1890s, a new type of propellant was developed by making use of an entirely different type of chemistry. When cotton is nitrated with a mixture of nitric and sulfuric acids, the product is known as nitrocellulose, and it burns very rapidly when ignited. Moreover, the combustion produces very little smoke so this propellant is known as “smokeless” powder. This book is not the place for a review of propellant technology, but it should be mentioned that the burning rate of nitrocellulose can be controlled to a great extent by the particle size. Therefore, it is possible to produce nitrocellulose and tailor it for use in cartridges having different sizes. Another development in propellant technology resulted in a type of powder known as double-base powder. This type of propellant makes use of nitrocellulose to which has been added a small percentage of nitroglycerin. In addition to varying the particle size of the propellant, various additives are included to impart particular properties such as flowing ease, reduction of static electricity, flash reduction, etc. By controlling these characteristics, a large number of types of propellants have been developed with burning rates that vary enormously. Some propellants work best in small cases such as the 22 Short or 25 ACP while others perform best in large cases such as the 300 Winchester Magnum.

Even with the use of smokeless powder, the problem of corrosion persisted. The cause was the residue that was produced from the primer that was a mixture that contained potassium chlorate. Because of the resulting corrosion, primers containing potassium chlorate became known as corrosive primers. Some ammunition was loaded with primers containing mercury fulminate and after detonation the resulting mercury reacted with the brass case which caused it to be weakened and thus unsuitable for reloading. In 1927, Remington introduced Kleanbore primers that contained a type of priming mixture that was noncorrosive. In most modern ammunition, the primer contains an explosive known as lead styphnate, but recently primers have been developed that do not contain lead. The motivation behind this is to reduce the amount of lead that is present in the air when firearms are used on indoor ranges. For use in rimfire cartridges, the priming mixture contains 35 to 45 percent lead styphnate, 25 to 35 percent barium nitrate, 18 to 22 pecent ground glass, and 6 to 10 percent lead thiocyanate as well as some other minor constituents. The function of the ground glass is to make the mixture more sensitive to friction when crushed in the rim. On the negative side, the small amount of ground glass remaining in the bore increases the rate of wear so that even though soft lead bullets are used, the bore eventually shows the effects of erosion. A 22 LR barrel will not last indefinitely. One of the characteristics of lead styphnate is that its explosive character is destroyed by oil and some organic solvents. If oil seeps into a case, it may cause the round to misfire. This is one reason for the substantial crimp given to 22 rimfire ammunition, the other being that a heavy crimp is necessary to give the correct “pull” that results in uniform velocities.

Remington ammunition has featured Kleanbore priming for many years as shown on these boxes of 22 LR cartridges from the 1950s.

Hyper-Velocity 22 Ammunition

Over the many years in which it has been produced, the 22 LR cartridge has undergone several changes. Most of these involved minor changes in velocity that resulted from the use of different powders or bullets of slightly different weight or shape. However, a radical departure from the norm occurred in 1977 when CCI introduced a round known as the Stinger. The new round utilized a 32-grain bullet that was driven by a heavier charge of powder that had a slower burning rate than the powder ordinarily used in 22 LR ammunition. To accommodate the larger powder charge, the case of the Stinger was made approximately one-tenth of an inch longer than the normal 22 LR case. The result was a round that produced a muzzle velocity of 1,640 ft/sec and a muzzle energy of 191 ft lbs. A flat trajectory resulted from the high bullet velocity so the effective range of the 22 rifle was increased. Owing to the high-velocity hollowpoint bullet, the new round was explosive in its effect on small pests or unopened cans of pop. The term “hyper-velocity” is generally applied to 22 LR ammunition that produces very high velocity.

Very soon after the Stinger was introduced, Winchester began producing a type of hyper-velocity round known as the Xpediter. This load utilized a 29-grain hollow-point bullet with a muzzle velocity of 1,680 ft/sec which gives a energy of 182 ft lbs. Federal followed suit by introducing the Spitfire which employed a 33-grain bullet with a velocity of 1,500 ft/sec and an energy of 165 ft lbs. The Winchester Xpediter was discontinued after being available for a few years, and the current Federal hyper-velocity load is not designated as the Spitfire although the ballistics are unchanged from that round.

Remington entered the competitive field of hypervelocity ammunition with two offerings. The Yellow Jacket features a 33-grain hollow-point bullet at 1,500 ft/sec giving a muzzle energy of 165 ft lbs while the Viper features a 36-grain truncated cone solid-point bullet at 1,410 ft/sec for an energy of 159 ft lbs. Aguila produces one other hyper-velocity round, and it drives a 30-grain bullet at an advertised velocity of 1,750 ft/sec to give 204 ft lbs of energy. However, the energy drops to only 93 ft lbs at a range of 100 yards. Another hyper-velocity round is the CCI Quik-Shok which uses a 32-grain bullet, but the bullet is designed so that it breaks into four pieces on impact. This produces a devastating effect on small varmints although penetration is generally less than with other types of ammunition.

Although the hyper-velocity ammunition gives dramatic effects at short ranges, the light bullets lose velocity more rapidly than do the heavier bullets used in conventional 22 LR ammunition. The result is that the remaining energy of the hyper-velocity ammunition is approximately equal to that of the slower rounds at a range of 100 yards or so. It is also generally true that hyper-velocity ammunition does not deliver the best accuracy in most rifles. There have been many reports published to verify that conclusion, and based on the results of tests conducted during this work it certainly true. Moreover, the longer cases of the Stinger and Quik-Shok pose a problem when used in rifles with so-called matchtype chambers because the case engages the rifling just in front of the chamber. With match chambers, the rifling extends back to the front end of the chamber so the bullet engages the rifling as a round is chambered. The makers of some rifles having match chambers warn against using the Stinger ammunition in those rifles. Bullet diameter for the 22 Short, Long, and Long Rifle is 0.223 inch.

With all of these developments and those described in the following sections, there can be little doubt that this is an exciting time for the rimfire shooter. More details on the performance of today’s rimfire cartridges will be presented in several later chapters in this book.

22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (WMR)

As wonderful as the 22 LR is, there are situations where more power is called for. In 1959, Winchester responded to that need by developing a cartridge that utilizes a case that is 1.05 inches in length and has a slightly larger diameter head and body than the 22 LR case (0.291” vs. 0.275” and 0.241” vs. 0.225”, respectively ) . Instead of using a bullet with a heel of smaller diameter that fits inside the case and a bullet that has the same diameter as the case, the new round used a 40-grain jacketed bullet of 0.224-inch diameter. This “magnum” rimfire is appropriately named the 22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (WMR), and the advertised velocity is 1,910 ft/sec from a 24-inch barrel. With a muzzle energy of 310 ft lbs, the 22 WMR is still the most powerful rimfire cartridge available. From the 20-inch barrel of my Ruger 77/22M, the velocity at 10 feet from the muzzle is below the advertised value by about 75 ft/sec.

The main drawback to the 22 WMR has always been the cost of ammunition. Although some special target ammunition in 22 LR may cost as much as $10 for a box containing 50 rounds, the cost of most of the ordinary types is only $2 to $3 per box. Some promotional ammunition in 22 LR can be bought for around $1 per box. Most of the types of ammunition in 22 WMR sell for $6.00 or more with the Remington Premier selling for around $10 per box. It is simply a fact of life that it costs around 12 to 20 cents per shot to fire a 22 WMR.

Three magnum rimfire cartridges are (left to right) the 17 HMR, the 5mm Remington, and 22 WMR. The 5mm Remington has been discontinued since the 1970s.

Being a larger and more powerful cartridge than the 22 LR, the 22 WMR could not be adapted to most actions that were designed specifically for the smaller cartridge. The actions had to be made slightly longer than those used on regular 22s, but very soon after the 22 WMR was introduced a large number of arms were available to chamber it. Winchester marketed the lever-action Model 9422M, and Ruger offered single-action revolvers with two cylinders, one in 22 LR and the other for the 22 WMR. Marlin, Savage, Anschutz, and others produced bolt-action rifles for the 22 WMR soon after its introduction. Currently, bolt-actions, lever-actions, and autoloaders are available in the magnum rimfire calibers as are many handguns (see Chapters 3 and 4).

The major complaint about the 22 WMR has centered on the subject of accuracy. It is popularly believed that the 22 WMR does not give accuracy that is quite the equal of that given by the 22 LR and some newer rimfire rounds. This perception may be in error, but that topic will be addressed more fully in later chapters.

5mm Remington Magnum

In 1970, Remington unveiled a rimfire magnum cartridge that offered even better performance than the 22 WMR. However, that cartridge deviated from the usual rimfire caliber because it was a 5mm or 20-caliber (actual bullet diameter is 0.2045”). The 5mm Remington Magnum cartridge produced 2,100 ft/sec with a ballistically efficient 38-grain bullet. As a result, the muzzle energy was 372 ft lbs, and the remaining energy also exceeded that of the 22 WMR at longer ranges. The 5mm Remington used a case that is slightly larger in diameter than that of the 22 WMR. Remington produced the Model 591 (box magazine) and Model 592 (tubular magazine) boltactions, but these were the only rifles produced for the 5mm Remington cartridge. Thompson/Center produced barrels chambered for the 5mm Remington to be used on the single shot pistols that they market. The 591 and 592 were discontinued in 1974 with a total of approximately 50,000 having been produced. The 5mm cartridges have become highly collectible with prices for a full box often being in the $50 to $75 range or more.

With greater energy and flatter trajectory than the 22 WMR, the 5mm Remington may well have been the best rimfire cartridge in modern times. Although the trajectory is not quite as flat as that of the 17 HMR with a 17-grain bullet, the 5mm Remington with its 38-grain bullet is a far more powerful cartridge. Part of the difficulty with the 5mm stemmed from the high pressure, which may have been as high as 35,000 lb/in2. The high pressure caused the case to expand into the extractor notches, which necessitated some changes in the chamber, bolt face, and extractor grooves. Given the propellants available today, it is likely that the remarkable ballistics of the 5mm Remington could be produced with a somewhat lower pressure. Moreover, there are several rifles available today that could probably serve as platforms for the excellent 5mm Remington cartridge. The Ruger 77/22M, Anschutz, Remington 504, CZ 452, and Kimber models come to mind immediately. We can only hope that rifles and ammunition in this outstanding rimfire caliber become available once again. If not, a 20-caliber cartridge based on a necked down 22 WMR case but utilizing the superb Hornady V-Max polymer tipped bullets would be very interesting and useful. Given the fine rifles that are available in 22 WMR caliber, it should be a simple matter to produce a 20 caliber cartridge based on that case.

17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire (HMR)

Perhaps no other new cartridge has generated so many printed words in such a short time by so many writers as the 17 HMR. Introduced in 2002, the 17 HMR was the first new rimfire cartridge since the short-lived 5mm Remington. However, the 17 HMR certainly will not suffer a similar fate! The number of rifles and handguns available in 17 HMR caliber is very large. This is natural because the 17 HMR case is simply a 22 WMR case necked down to hold a 17-caliber bullet. Therefore, a firearm designed around the 22 WMR can be made into a 17 HMR simply by changing the barrel. Even the magazines that hold 22 WMR cartridges will feed 17 HMR cartridges. Because so many firearms in 22 WMR caliber were already in production, there are now many that are also produced in 17 HMR.

Nominal bullet diameter for the 17 HMR is 0.172”. The original load consisted of a 17-grain Hornady V-Max polymer tipped bullet that was loaded to a velocity of 2,550 ft/sec giving an energy of 245 ft lbs. The well-shaped bullet has a ballistic coefficient of 0.125 so it holds velocity well which results in a rather flat trajectory that makes hits on small pests possible out to 150 yards or more. Although many larger varmints have been taken with the 17 HMR, the cartridge is at its best when used on species like ground squirrels, crows, pigeons, and prairie dogs. Early reports by some writers described the use of the 17 HMR on species as large as coyotes, but many reports have also described failures of the tiny bullets on larger pests like groundhogs, foxes, and coyotes. One of the most interesting discussions on the 17 HMR is that by C. Rodney James which was published in Gun Digest 2005. In an article published in the February 2005 issue of Predator Xtreme, Ralph Lermayer has related some of his experiences on the failure of the 17 HMR as a cartridge for use on larger varmints. Recently, loads employing 20-grain hollow-point bullets having a muzzle velocity of 2,375 ft/sec have been introduced to reduce the explosive character. This ammunition may help reduce bullet fragmentation, but the tiny 17 HMR was never really intended for use on larger species of varmints. Nonetheless, the 17 HMR is a great little cartridge that gives outstanding accuracy, and we will have a lot to say about it in other chapters of this book. Incidentally, it was the development of suitable propellants that made the ballistics given by the 17 HMR possible. Had such propellants been available at the time the 5mm Remington was introduced, the 17 HMR might never have been developed.

Calibers available to the rimfire shooter are (left to right) the 17 Aguila, 17 Mach 2, 17 HMR, 22LR, and 22 WMR. Although all are useful, each has its advantages and disadvantages.

Introduced in 2004, the 17 Mach 2 is gaining wide acceptance. Note the mention on the label of the “first production run” on this box.

Two cartridges that the author (and many others) would like to see brought back are the 5mm Remington (left) and the 25 Stevens (right).

17 Mach 2

The 17 HMR represents a 22 WMR case necked to hold 17-caliber bullets, but consider the potential of a 22 LR case necked to hold a 17-caliber bullet. An enormous number of rimfire rifles could become 17-caliber rifles simply by changing the barrels. In order to produce a cartridge that would hold enough powder to give a high velocity, the case used could be that of the CCI Stinger which is 0.700 inch long rather than 0.600 inch of the normal 22 LR. These procedures are exactly those used by Hornady and CCI to produce the 17 Mach 2, which launches a 17-grain bullet at 2,100 ft/sec (which is approximately twice the velocity of sound hence the name Mach 2).

However, there is a potential problem with simply changing the barrels on 22 LR semiautomatics. The new 17 Mach 2 burns more powder than a 22 LR so the chamber pressure remains high for a longer period of time. This causes the bolt to be driven to the rear at higher velocity than when 22 LR cartridges are fired. To keep the bolt from being driven back with enough force to damage the action, a heavier bolt must be used or a stronger recoil spring or both. There is no problem with bolt-action 22 LR rifles becoming 17 Mach 2 pieces, but in the case of autoloaders, changes other than merely switching barrels may be necessary.

Firing a 17-grain bullet with a muzzle velocity of 2100 ft/sec, the 17 Mach 2 produces a muzzle energy of 166 ft lbs. This is less power than that produced by some high performance 22 LR rounds so the 17 Mach 2 is a rifle for small pests. Accuracy as good as that produced by any rimfire is the strong point of the 17 Mach 2. With its flat trajectory, small pests are in danger out to around 125 yards when the shooter does his or her part. However, two of the last three boxes of 17 Mach 2 ammunition that I bought cost $6.99 each while the other was $5.99. This is approximately two or three times the cost of good quality 22 LR ammunition and is about the same as 22 WMR ammunition. The difference probably would not matter to a pest hunter, but it certainly would to the casual plinker.

17 Aguila

A recently introduced 17-caliber cartridge is known as the 17 Aguila. While the 17 Mach 2 utilizes the longer CCI Stinger case necked to hold a 0.172 caliber bullet, the 17 Aguila employs a 22 LR case of normal length. Powder capacity of the 17 Aguila is less than that of the 17 Mach 2 so a muzzle velocity of 1,850 ft/sec is produced with a 20-grain bullet (remaining velocity at 100 yards is 1,267 ft/ sec). However, bolt-action rifles and most autoloaders that fire 22 LR cartridges can be converted to 17 Aguila caliber simply by changing the barrels. Even though the 17 Aguila produces slightly lower velocity than the 17 HMR, the difference is not enough to make any practical difference in hunting use especially since the 17 Aguila uses a 20-grain bullet. Shots should be limited to somewhat shorter ranges with the 17 Aguila, but both are suitable for small game and small pests. The almost unknown 17 High Standard cartridge is apparently almost identical to the 17 Aguila.

Newest of the rimfire cartridges is the 17 Agiula, which is a 22 LR case necked to hold a 17 caliber bullet.

Although several obsolete rimfire cartridges have been interesting and historically important, the choices available today make this the most exciting time in rimfire history. Hopefully this will become more apparent as you read this book.

In 17 HMR, Hornady markets loads with a 17-grain polymer tipped bullet (left) or a 20-grain hollow-point (right).