Читать книгу The Turkish Arms Embargo - James F. Goode - Страница 12

Оглавление3

Making Turkey Pay

Concurrently with the opium crisis came the Cyprus imbroglio. On the morning of Monday, July 15, 1974, Cypriot National Guardsmen, led by their Greek officers, attacked the presidential residence in Nicosia. The objective was to kill the president, Archbishop Makarios III, and establish a new government under Nikos Sampson, a champion of enosis, or union with Greece; Sampson was also a known terrorist who had personally killed Turkish Cypriots. Makarios narrowly escaped and eventually made his way to London. The Sampson government lasted only eight days before local and international criticism—and a Turkish invasion—forced him from office. Glafkos Clerides, a more moderate Greek Cypriot and the speaker of the House of Representatives, became acting head of state. Sampson’s fall triggered a backlash against the military junta in Athens, which had instigated the coup (code-named Aphrodite) in the mistaken belief that a successful takeover of Cyprus would restore its tarnished image at home. Instead, the Nicosia debacle led to collapse of the Regime of the Colonels and restoration of popular rule after seven years of a harsh right-wing dictatorship in the birthplace of democracy. Exiled conservative political leader Constantine Karamanlis (1907–1998) was invited home from exile in Paris to form a government, pending parliamentary elections.

International Responses

Although the coup proved a dismal failure, it set in motion larger events that could not easily be reversed. The Turkish mainland lay only 65 kilometers from the northern shores of Cyprus, whereas Greece was more than 800 kilometers away. The Turkish government kept a careful eye on developments on the nearby island, where approximately 20 percent of the population (180,000) was Turkish. This Turkish minority had established enclaves across the island, where residents lived largely walled off from their Greek Cypriot neighbors.

In cities such as Paphos in the southwestern part of the island, the Turkish community lived behind a wall topped by blue UN watchtowers. The United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus had been established in 1964 during a time of increasing tensions between the Greek and Turkish communities. Turkish Cypriots taxed themselves and maintained their own education system. Young Turkish and Greek Cypriots grew up almost completely separated from each other. Groups of Turkish men and boys ventured into the Greek part of the city only on Fridays to purchase necessities not available on their side, but they did not linger there. The Makarios government in Nicosia had shown little interest in reversing this informal separation between the two communities. In fact, it had contributed to the situation by steadily whittling away at the minority guarantees provided in the 1960 constitution.1

Along with Greece and the United Kingdom, Turkey was a guarantor of the 1960 constitution, which had established an independent Cyprus and provided many safeguards for the rights of the Turkish minority. Thus, when the coup took place and Sampson became head of the post-Makarios government, Turkey’s prime minister, Bulent Ecevit, believed he must act. Furthermore, Ankara determined that as a guarantor power, it had a right to take action to protect the Turkish Cypriot minority.

Flare-ups of intercommunal violence had taken place repeatedly since 1960, most notably in 1964 and again in 1967. The Turkish government came close to launching an invasion in each of those years, but the Americans intervened, including the infamous Johnson letter of 1964. The soldiers remained in their barracks, but the Turks were bitter about the lack of support from Washington.

Ten years later, in the summer of 1974, the Nixon administration was in disarray due to the Watergate scandal, and the president was edging toward resignation. Ankara knew that this time, there would be no Nixon letter. This seemed to be the perfect moment to secure the future of the Turkish Cypriot minority. Both Athens and Washington were in a confused and weakened state, and Greek Cypriot forces could hardly resist a Turkish onslaught.

Hurried talks took place in London from July 16 to 20, but it was clear that Prime Minister Ecevit was in no mood for compromise. On July 20, after Turkish demands had not been met, the Turkish army invaded Cyprus. Having received the coded message “Ayse tatile cikti” (Aisha went on holiday), the Turks seized territory around the port city of Kyrenia, a center for tourism on the northern coast of the island and home to a large number of Turkish Cypriots.2 The army seized the city and its hinterland and a narrow corridor to the inland capital, Nicosia, amounting to less than 5 percent of the island. On July 22 a cease-fire negotiated by Britain and the United States took effect, and talks were scheduled to resume two days later in Geneva under British sponsorship. Both the Greek junta and the Sampson government collapsed on July 23.

The explosion of violence on Cyprus surprised the Americans, whose eyes had been fixed on a brooding President Nixon, who had withdrawn to his retreat in San Clemente, California. During a meeting of the Washington Special Action Group on July 17, chaired by the secretary of state, officials had concluded that the Turks were unlikely to invade. Kissinger could not understand why the Turks were insisting on returning Makarios to power, for he had been their archenemy. In any case, the United States had to make its position known to Turkey as quickly as possible: Washington would support an acting government under Glafkos Clerides for six months, followed by elections. Undersecretary of State Joseph Sisco, one of Kissinger’s top aides, made a hurried call to the Turkish ambassador to present the American thinking, and then he left for London to explain to Makarios and Ecevit in person the US proposal.3

From the British capital, Sisco proceeded to Athens and Ankara. In the Greek capital, the collapsing junta agreed to a number of compromises to stabilize the situation on Cyprus, including the acceptance of a single Turkish enclave on the island. But these concessions came too late. The proponents of enosis had made a colossal blunder, opening the door for a Turkish invasion in the name of restoring the 1960 constitution. In Ankara, Sisco was waiting outside the meeting room of Turkey’s National Security Council on July 20, while inside, Ecevit was making the decision to invade.4

Subsequent talks in Geneva made little progress. Neither the Greeks nor the Turks would shift their position, and British Foreign Secretary James Callaghan became increasingly frustrated. Kissinger rated Callaghan’s chances of success as very slim. Perhaps Kissinger hoped the feuding parties would eventually turn to him to work out a settlement. Meanwhile, the meetings in Geneva dragged on into August.5

The embassy in Ankara reported general agreement between the military and the Ecevit government on the policy toward Cyprus. Furthermore, most Turks believed they should gain all they could from the current situation. They would not return to the status quo ante. According to one observer, “there was no other issue, domestic or foreign, on which there was such unanimity in Turkey.” Ecevit was a tough negotiator, as he had proved earlier during the opium crisis. As it turned out, he was not the moderate that his former Harvard University professor, Henry Kissinger, might have expected. The Turks made it clear that they wanted two separate communities on Cyprus, each with full autonomy. There could be a central government in Nicosia, but with limited powers. Callaghan wanted negotiations to take place between Glafkos Clerides and Rauf Denktash, the Turkish Cypriot leader, but the government of Turkey thought that would be a waste of time. Ecevit wanted the guarantor powers—Greece, Turkey, and the United Kingdom—to make the important decisions at Geneva, with the details to be worked out later. Ambassador Macomber was not hopeful.6

Turkey had been building its force on Cyprus since the first invasion, and by August 14, it numbered 40,000. On that day, having exhausted his patience in Geneva, Ecevit gave the order to recommence Operation Attila to gain by force what had eluded Turkey in the negotiations. Facing little opposition, the superior Turkish forces seized almost 40 percent of the island, including the important city of Famagusta in the east and the international airport at Nicosia. The Turks took more than they had planned to retain as part of the Turkish Cypriot sector, perhaps taking a page from the Israelis after the 1967 Six-Day War—that is, use land as leverage to achieve acceptance of a new status quo. (Whatever their original intentions, the boundaries have remained fixed since that time.)

Many more thousands of Greek Cypriots became refugees. Large numbers of Turkish Cypriots, who lived on the wrong side of the front lines were uprooted as well. Some of the latter ended up seeking shelter on the British air bases at Akrotiri and Dhekelia. This was a sad fate for an island population that had enjoyed a higher standard of living than either the Greeks or the Turks prior to the coup d’etat and the Turkish invasion.7

The Karamanlis government immediately withdrew Greece from the military structure of NATO, much as Charles de Gaulle had done with France in 1966. The prime minister was protesting an apparent lack of support by the members of the military alliance, including the United States. He had expected them to take firmer action against Turkey for its invasion of Cyprus.

The Turkish government seemed to agree with Karamanlis that the United States supported its attempt to resolve the Cyprus problem. Even the Turkish media praised the United States for following “the wisest policy among the Western powers despite the opium issue.” The United States took Turkey’s side, it was said, because it recognized Turkey’s greater importance relative to Greece. One major paper, Cumhuriyet, announced that the United States understood the Turkish point of view.8

In private, Turkish leaders admitted that the United States had tried to be evenhanded, in contrast to the anti-Turkish sentiments expressed by most Western governments. This sensitivity was appreciated in Ankara, and the newly installed Ford administration might have been able to negotiate with the Ecevit government and actually be listened to.9 Unfortunately, American policymakers did not take advantage of this opportunity in the interim between the initial invasion on July 20 and the dramatic expansion twenty-five days later.

Kissinger’s response puzzled observers at the time and has confounded scholars ever since. It seems that he misjudged the Turkish prime minister, who proved to be more of a risk taker than any of his recent predecessors. How else can we account for the secretary of state’s apparent lack of preparedness to engage the looming crisis with his arsenal of diplomatic skills? At other points in his tenure, Kissinger might have taken control and set out in person for the eastern Mediterranean, rather than sending a deputy. His sudden appearance in Athens or Ankara would have conveyed a sense of urgency to the respective parties. He was, of course, facing a major crisis at home as the Nixon presidency unraveled. With the US government in disarray—Nixon was holed up in California when the first invasion took place, and Gerald Ford had been in the White House less than a week when stage two of Attila was launched—perhaps he felt that he could not leave Washington.

Historians reflecting on these developments have concluded that the United States—that is, Henry Kissinger—could have done more to forestall the Turkish attack. Perhaps he underestimated the influence Washington could exert on Ankara or feared that the Turks would leave NATO altogether if Washington pressed too hard. Although the secretary of state might have leaned on Athens to be more flexible or could have joined the British at Geneva, the Americans were unwilling to tip too much in either direction, lest they destroy their bona fides if they were asked to mediate the dispute.

One cannot dismiss the possibility that Kissinger welcomed Turkey’s cutting of the Gordian knot, ending once and for all the troubled island’s periodic eruptions. After all, Dean Acheson, for whom Kissinger had the greatest respect, had concluded in 1964, after his failed mission to resolve an earlier crisis, that partition of the island might be the only long-term solution. He proposed the Acheson plan, of which his biographer Robert Beisner writes, “Acheson’s visibly pro-Turkish recommendations shaped Washington’s approach to Cyprus for a generation.”10

Greek Americans to Arms

Although Turkey had strength of arms in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean region, the Greeks and Greek Cypriots quickly attracted international sympathy and support. Nowhere was this more evident than in the United States, for Americans had a long history of championing the Greek cause. This began in the early nineteenth century, when the Greeks struggled for independence from the Ottoman Empire. An American journalist at the time referred to American support as “Greek fever.” Rooted in the mistaken belief that modern Greeks were the direct descendants of ancient Greeks and that success against the Turks would restore the glory of Athens and the Greek city-states, many Americans supported the Greek war of independence in the 1820s. At that time, the American press “focused exclusively on Turkish abuses,” feeding sympathy for the Greek side while ignoring the massacre of Muslim civilians during the war.11

More recently, American activists had opposed the rule of the military junta (1967–1974) in Greece. Several members of Congress, including Representatives Donald Fraser (D-MN), Ogden Reid (R-NY), and Donald Edwards (D-CA) and Senator Vance Hartke (D-IN), served on the board of the US Committee for Democracy in Greece. They worked to encourage Congress to cut off military assistance to the Regime of the Colonels in Athens. This passion for Greece would be rekindled in the Cyprus crisis of 1974.12

Greek American associations had been active from the first days of the Cyprus crisis in mid-July. They represented an influential community of an estimated 2 million immigrants and their descendants, most of whom had come to the United States from rural areas of the Ottoman Empire and the Peloponnesus in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Predominantly single men arrived at first; they became laborers on the railroads or factory workers on the East Coast, especially in Boston, New York, and Baltimore, and in Detroit and Chicago in the Midwest. Soon they established themselves in small businesses, grocery stores, bakeries, and so forth. A second wave of immigrants came directly from Greece after World War II to escape the devastation and civil war. Members of the Greek American community became quite prosperous and expressed a considerable interest in politics. In the late 1960s they participated in the revival of ethnicity common to other immigrant groups in the United States, encouraging strong attachment to Greek traditions.

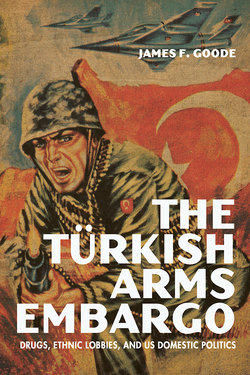

Poster showing a Turkish soldier on Cyprus, with Ecevit to the left (English comments by an unknown source). (Courtesy Paul Tsongas Papers, Center for Lowell History, University of Massachusetts, Lowell)

Influential associations, such as the American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association (AHEPA), responded even more vociferously once Turkish forces crossed the cease-fire lines on August 14. Unlike the initial invasion, it was difficult to justify the expansion of Operation Attila, and this new offensive was being carried out with US-supplied weapons. One flyer captured the mood at the time. It paired a description of Attila the Hun with a description of this new “Scourge of God”—the Turkish army—which was allegedly committing so many crimes on Cyprus that “the conscience of all civilized men shudders.” How appropriate, wrote the author, that the campaign was named after the king of the Huns. The Turks were likely unaware that, to many Americans, the name “Attila” conjured ancient images of death and destruction. From the American perspective, the Turks could not have chosen a more inappropriate name for their offensive, and by doing so, they provided a propaganda advantage to their enemies.13

The Turks’ opponents frequently presented them as the “Other” and cherry-picked their way through history to make facts conform to strongly held beliefs. In countless letters to government officials, they expressed the depths of their bitterness. In one example, Dr. Daniel Kavadas, a dentist who headed the Columbia, South Carolina, chapter of AHEPA, wrote to Congressman Floyd Spence (R-SC): “What the government of Turkey is striving to achieve today in Cyprus is exactly what Hitler’s Third Reich strove to achieve—and achieved—in the annexation of the whole of Czechoslovakia some thirty-five years ago by using the minority problem as an excuse.” Comparisons with the Nazis appeared repeatedly in flyers and various other publications.14

These characterizations might have seemed tame compared with the telegram from one activist referring to “the Turkish insane animals.” In a letter to President Ford, another concerned American, Basil Rodes, noted that history was replete with examples of “the death and destruction visited upon peoples in Asia Minor, Europe, and North Africa by the Turks. The Turks are repeating the same practice of death and destruction in Cyprus today. The Turks had contributed nothing to the human race and its civilization, but they have spread death and destruction throughout the ages.” Another wrote to Secretary Kissinger, emphasizing a common theme: “The major portion of Turkey today is a barren wasteland … buildings and monuments created by their ‘restless minorities’ now lie in ruins, further desiccated by the indolent and feckless peasants [Turks] who carry off pieces of building stone as needed, to reinforce their own dilapidated, shanty-like dwellings.”15

Occasionally, such vitriol made its way into the publications of the major Greek American organizations. An article in the Ahepan stated, “From the very first day that the battle started, the Turks displayed that they are still the same savage people.” A recounting of Greek-Turkish relations recalled all the harm done to the Greeks in World War I, including the massacres of Greeks and Armenians and the forced resettlement of Greeks from Asia Minor to Greece. The article was silent on the Greek invasion of Anatolia after the war (1919–1922) and on the repatriation of a smaller Turkish population from Greece to the Republic of Turkey.16

One of the most troubling developments was repeated charges of atrocities on both sides. These were more numerous coming from Greek Americans, who had more outlets to present their arguments to the American public. There were tales of looting, rape, and intentional destruction of churches in the area under Turkish army control. The Cypriot embassy in Washington circulated an information sheet in mid-November 1974, claiming to provide ”factual evidence” that the Turks were guilty of the greatest crime of all, “GENOCIDE,” against the Greek population, murdering in cold blood hundreds of innocent women and children and crippled and old men. They had allowed “repeated and continual rapes of women from the age of twelve onwards on an organized basis by the officers and men of the Turkish army, reminiscent of Nazi concentration camps.” Even Archbishop Iakovos added to the charges. In a letter to Congressman John Brademas (D-IN), the archbishop’s office claimed that, among other crimes, “priests have been beaten to death, one priest attempting to rescue his daughter from being raped was savagely beheaded.”17

Yet there was little incontrovertible evidence to support these lurid tales. When an AHEPA delegation to Cyprus met with Dr. Vasos Vasilopoulos of the Ministry of Health, he disputed reports that Cypriot women’s breasts had been cut off or that boys had been emasculated. There were enough real problems, he explained, resulting from the destructiveness of modern warfare. Still, the exaggerated accounts did not subside.18

The government of Turkey also publicized questionable claims of atrocities, in spite of advice from the US embassy not to do so. A UN report concluded that, after an investigation of thirty alleged cases of so-called Greek atrocities against Turkish Cypriots, none had been verified. The UN did verify, however, a massacre of Turkish Cypriot civilians at the village of Tokhni, between Limassol and Larnarca, and also at Maratha. The US embassy in Nicosia reported that 90 percent of Turkish Cypriots released as prisoners of war or detainees chose to head north, even though their families were often in the southern part of the island. Turkish Cypriots were gathering in the area controlled by the Turkish army, quickly “Turkifying” the northern sector.19

Even responsible spokesmen sometimes wandered into this murky landscape. Such was the case when notoriously outspoken Congressman Ed Koch (D-NY) recalled Ottoman barbarities toward the Armenians and suggested that “Turkish events in Cyprus today may yet warrant similar distinction.” More surprising were statements by Congressman Brademas printed in the English-language Turkish Daily News. “The government of Turkey has in my opinion acted in a very uncivilized way,” he observed. He followed this with a reference to Hitler’s attempt to outgun everyone, noting, “might is right.” The usually cautious congressman might not have understood how much the Turks resented such unfavorable comparisons, which had a long history.20

Throughout the last decades of the Ottoman Empire and into the early years of the Turkish republic, foreigners repeatedly made claims about the Turks’ barbarity, their animal-like natures, and their lack of any civilizing qualities. These outrageous allegations seemed endless. It was in part to end such derogatory assertions by supercilious Europeans and Americans that Ataturk launched his movement to transform the Turkish nation, to make all Turks proud of their heritage and ethnicity. Symbolic of this goal was the founder’s widely publicized statement, “Happy is the man who calls himself a Turk.” This was not mere chauvinism; it was an attempt to encourage a new and necessary confidence among his fellow citizens. In this, he appeared to have remarkable success. Ataturk also positioned Turkey closer to Europe, distancing it from the Middle East.21 Now, in the mid-1970s, many of the former stereotypes were resurfacing among foreign observers.

The Greeks and many of their Greek American supporters argued that the Turkish Cypriot minority had been treated well in Cyprus and got on well with their Greek Cypriot neighbors. They claimed that a minority of extremists, acting in accord with the Turks in Ankara, was forcing the Turkish Cypriots to live in isolated enclaves throughout the island. Father Evagoras Constantinides, a Cypriot by birth and a member of a delegation meeting with Secretary Kissinger and his deputy Robert Ingersoll on August 26, 1974, asserted that “he was not aware of any oppression of the Turks by the Greeks in Cyprus” and claimed that “insurrectionist Turks always held at least one member of a family hostage to ensure the return of the others.” These seem, at best, only partial explanations for the continuing tension and violence between the two communities throughout the 1960s and early 1970s.22

Of the Greek American organizations actively pursuing justice for Cyprus, none surpassed AHEPA. Founded in 1922, it had thousands of members in all fifty states and possessed an effective structure for activating the larger community. On July 22, just two days after the initial Turkish invasion, AHEPA announced a July 24 press conference in Washington, where leaders of twenty Greek American societies would demand the withdrawal of Turkish forces from Cyprus. AHEPA would continue to be one of the leading critics of Turkish actions on the island and of the Ford administration’s policies toward the crisis as well.23

Although AHEPA was the oldest and best known of the Greek American associations, there were others that took on important roles. The American Hellenic Institute (AHI) limited its membership of approximately 200 individuals to professionals and academics. Headquartered in Washington, DC, it was led by Eugene Rossides, who had served in the Treasury Department under Nixon and was a law partner of William Rogers, former secretary of state and attorney general. Rossides knew how to get things done in the capital. He became a leading spokesman on Cyprus and was often called to testify before congressional committees on behalf of Greek Americans. His model for AHI was the highly successful American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). According to political scientist Paul Watanabe, who has studied the organization closely, “whenever any key votes were in the offing, AHI-PAC reviewed its congressional profiles in order to determine the most effective strategies to persuade individual congressmen. Armed with this information, AHI-PAC dispatched at least two influential Greek American constituents, who were carefully preselected, to contact, in person if possible, each congressman.”24

The third of the “big three” organizations—those whose representatives were regularly invited to testify at congressional hearings—was the United Hellenic American Congress (UHAC) in Chicago, a center of Greek American activism. Andrew Athens, president of Metro Steel Corporation and a close ally of Senator Charles Percy (R-IL), headed this organization. It was said to be the creation of Archbishop Iakovos, and it maintained close ties to the Greek Orthodox Church. UHAC organized large public protests to support the arms embargo and aid for Cypriot refugees.25

Archbishop Iakovos, primate of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of North and South America, exercised an equally powerful voice. He was born Demetrios Koukouzis on the Aegean island of Imbros in the Ottoman Empire in 1911 and came to the United States when he was twenty-eight years old. He was ordained a priest in 1940 and became archbishop in 1959; he would serve in that post until his resignation in 1996. A strong supporter of the civil rights movement, Iakovos joined hands with Martin Luther King Jr. at the Selma march in March 1965. He appears next to King in the iconic photo at the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

On Friday, July 26, the archbishop telephoned Congressman John Brademas, one of only five Greek Americans in the House of Representatives. Brademas, a Rhodes scholar, had become the first Greek American member of Congress when he was elected to the House in 1958, and he was now the spokesman for this small group of representatives. The archbishop expressed his concern about the buildup of Turkish forces on the island. Iakovos seemed to be out ahead of the Indiana congressman, who knew few details and initially argued that Turkey’s actions were justified, given the coup against Makarios. Iakovos told Brademas that the Greek Orthodox Church could not look the other way when humanitarian issues were involved. From the outset, he also believed that the United States had encouraged the Turks to invade Cyprus. Brademas promised to contact the archbishop again on Monday, after his meeting with the other Greek American congressmen and a possible briefing at the State Department.26 That same day (July 26), Brademas and his Greek American colleagues—Skip Bafalis (R-FL), Peter Kyros (D-ME), Paul Sarbanes (D-MD), and Gus Yatron (D-PA)—sent a congratulatory note to Prime Minister Karamanlis, praising Greece’s return to free and democratic political institutions.27

In recent years, the Greek American community had split over how to relate to the military regime in Athens. Those who opposed the junta and wanted to cut US arms to Greece organized groups such as the US Committee for Democracy in Greece to lobby the US government. Others tolerated the junta and seemed content to carry on business as usual, just as the Nixon administration had done. With the junta’s disappearance, they could all unite in their criticism of Turkey’s actions in Cyprus.28

As arranged, Brademas spoke again with Iakovos and shared what he had learned at the State Department about the situation on Cyprus. He assured the archbishop that he and the other Greek American congressmen would work together on behalf of Cyprus. He suggested that Iakovos and other Greek American leaders write to officials in Washington to protest the continuing Turkish buildup on the island.29

Iakovos was one step ahead of the Indiana congressman, having called an important meeting for Tuesday, July 30, in New York City, where he resided. He convened the Archdiocesan Council and the presidents of many Greek American federations and societies at the St. Moritz Hotel in Manhattan. The gathering’s purpose was to organize and take immediate action to bring relief to the people of Cyprus. The archbishop was clearly in charge. After much discussion, it was unanimously decided that he would appoint members to a committee to coordinate assistance. He would also select a representative in each state to organize a local committee to expedite the national program’s work. The attendees decided to ask Congress to cut off all aid to Turkey if that nation had not complied with the UN cease-fire resolution within thirty days.30

Kissinger struggled amid the rising chorus of ethnic protest. On August 21, 20,000 Greek Americans marched in Chicago’s Grant Park. AHEPA sent circulars to all its chapters instructing them to send telegrams asking their congressmen to cosponsor House Resolution 1319, calling for an aid cutoff. On August 18 AHEPA’s annual convention opened in Boston, and over the next week, delegates representing the organization’s 50,000 members focused on Cyprus and what they considered the failed policies of the Nixon and Ford administrations. On August 21 a delegation visited UN headquarters to meet with Undersecretary-General Frank Bradley Morse to express their concerns. Two days later, AHEPA supreme president William P. Tsaffaras and two other delegates met with the secretary of state in Washington to hear his defense of US policy. They reported a subdued Kissinger who blamed the US failure to respond to the threatened Turkish invasion on the disordered situation in Washington, with one president on the point of resigning and another unelected president about to take office. The delegates told him that if justice for Cyprus were not forthcoming, AHEPA members and Greek Americans in general would turn their anger against the president. “We will know what to do in the next election,” they warned.31

Kissinger introduced the delegates to the new US ambassador to Greece, Jack Kubisch. On the spur of the moment, in response to an invitation from the delegates, Kissinger told the ambassador to go to Boston immediately and speak to the convention. He did, and for a moment, Kubisch became a symbol of the new administration’s good intentions.32

On August 24, the final day of the conference, AHEPA took two important steps. It voted to raise $100,000 through its many chapters to continue to seek justice for Cyprus. It also approved the creation of an ad hoc Justice for Cyprus Committee to lead the campaign.33

It is little wonder that the Ford administration often seemed overwhelmed at the extent and vociferousness of these lobbying efforts. Activists seemed to be everywhere, sending postcards and telegrams; placing ads in local, regional, and national newspapers; and sponsoring rallies for Cyprus. Gerald Ford had assumed the presidency in the middle of the Cyprus crisis, and he had no time to ponder this issue or any of the others he had inherited from his predecessor. He had little choice but to retain most of Nixon’s appointees, even if their personalities clashed with his own, such as that of Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger. In time, these awkward relationships would be resolved. Fortunately, Ford worked well with Kissinger, who was delighted to continue his tenure as secretary of state and national security adviser.

President Ford, Secretary of State Kissinger, and other top State Department officials met on numerous occasions with the AHEPA committee, Archbishop Iakovos, and delegations of congressmen who supported an embargo. The administration tried to be patient, but increasingly it came to view the Greek American activists as representing a special interest, to the detriment of the broader American interest. The executive needed to have a relatively free hand to negotiate with foreign countries, and the White House believed that an embargo would make the Turks less amenable to compromise. President Ford liked to tell visitors that he was a member of the AHEPA chapter in his hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan, and that he counted a number of Greek Americans there as his friends. But these connections were of little help to him in Washington.

When President Ford appeared on television and stated that “our foreign policy cannot be simply a collection of special economic or ethnic or ideological interests … the executive must have flexibility in the conduct of foreign policy,” AHEPA responded with a challenge. “One can only assume,” it said, “that the President believes that Americans of Greek descent need to be ‘put in their place’ and that we should be reprimanded for voicing our opinions on the Cyprus matter! … Is foreign policy the sole possession of one, two, or twenty men?”34

In part, the president was grappling with a new phenomenon spawned by the civil rights movement: an ethnic revival that exhibited nationalist fervor whenever issues related to the homeland cried out “for emotional involvement.” For many, ethnicity had become a social good. As historian Salim Yaqub recently wrote, “By 1970, it was much safer and more acceptable for people with dark complexions, strange names, and in some cases foreign accents to criticize the United States … boasting their own long heritage of stable and industrious ethnic communities in America.” This movement was a protest against “the very fabric of WASP culture,” and in this case, President Ford, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, and even Secretary Kissinger represented the WASP establishment, which was trying to dictate how Greek Americans should behave. But that minority was not going to be shamed into silence.35

At the local level, too, new activist groups sprang into existence around the country to pursue goals similar to those of the national organizations. In Minneapolis–St. Paul, for example, a group calling itself the Minnesota Friends of Cyprus (MFC) actively engaged these issues in the Twin Cities, seeking funds, raising consciousness, lobbying the state’s congressmen and senators, and urging its members to write letters to federal officials. The MFC remained active until the end of the 1970s. Another example was the Save Cyprus Council of Southern California, chaired by Professor Theodore Saloutos (1910–1980) of UCLA, the noted historian of the Greek immigrant community.

Saloutos left a detailed diary of these early days of organization and protest, providing an intimate look at the inner workings of the Greek American lobbying effort. It covers his various activities on both coasts during the critical period from August 30 to September 17, 1974. He eagerly assumed his new role, helping to organize meetings and protests against the Turkish invasion. He corresponded regularly with the offices of Congressmen Edward Roybal (D-CA) and Thomas Rees (D-CA) and Senator Alan Cranston (D-CA). He also established contact with Mike Minashian, an Armenian activist; they shared an antipathy toward the Turks, and their respective organizations cooperated in the defense of Cyprus. Representatives of their two groups met with Congressman Roybal at his Los Angeles office on September 4. They had been advised beforehand that the congressman was particularly concerned about Turkey’s cultivation of the opium poppy, having traveled to Turkey with a group of his colleagues to study the problem. Thus, Saloutos and the others emphasized that issue in their meeting. Roybal, who served on the House Appropriations Committee, thought that opposition to poppy cultivation provided the best point of attack for curtailing aid to Turkey. A number of committee members already supported such a move, and others could be persuaded, he thought. Roybal urged them to publicize their activities. Saloutos came away with a view of Roybal as “a modern, unassuming man of integrity who speaks for the common people.”36

Of course, not everything went as planned. On September 3 Saloutos complained about an atrocity story, accompanied by a picture of slain Turkish Cypriots, that appeared on the front page of the Los Angeles Times. He viewed this as an unfair allocation of space and a form of “yellow journalism.” A rally on September 6, on the south lawn of city hall, turned into a fiasco. It was poorly organized; there was no spokesman to meet with the media, and prominent personalities had never been invited. It was a disaster, according to Saloutos. That evening, however, things began to look up. Saloutos participated in a meeting at St. Sophia Cathedral, where John Brademas was the principal speaker. The congressman was visiting California to raise money for his reelection campaign. The Cyprus committee also raised $600 at the event. Brademas impressed Saloutos with his sophisticated presentation.

Four days later, Saloutos arrived at AHEPA headquarters in Washington, DC. There, he met with Eugene Rossides, who was then in the process of creating the American Hellenic Institute “to serve as a round-the-clock office on all legislation present and future dealing with the Cyprus question.” Rossides planned to send information to AHEPA and church-based organizations, hoping to line up their public support. Saloutos read over the draft proposal and made a few suggestions. He recommended that, for academics at least, the AHI membership fee should be reduced from $500 to $100. He also met Rossides’s assistant, a Cypriot who told him that most Greek Cypriots opposed enosis. The Greeks, he said, could not govern themselves, so “why should they seek to govern Cyprus 500 miles away.” It seemed that no one knew for certain how many Greek Cypriots favored union with Athens and how many wanted to maintain independence.37

On September 11 Saloutos lunched with his good friend George C. Vournos, a Washington-based lawyer and former supreme president of AHEPA (1942–1945). Vournos asked Saloutos to read a draft article he had written for a scholarly journal in which he criticized the National Herald of New York, a leading Greek American paper; AHEPA leadership; and even Archbishop Iakovos and the Greek Orthodox Church for their earlier support of the junta, which, he argued, had contributed to the Cyprus tragedy. Vournos also suggested that academics should do more research and publish more work on internal Turkish issues such as the opium trade, the Armenian genocide, and Turkish militarism. Saloutos told him that it was a good piece of writing but too polemical.

On Friday, September 13, Saloutos met with Dr. Hratch Abrahamian, an associate professor at the Georgetown University School of Dentistry and a leading Armenian activist. He also served as head of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF). The two men had lunch together, and Abrahamian shared his family history, telling Saloutos how his parents had fled to Iran from Smyrna to escape the violence and chaos there in 1922. Later, Saloutos took Abrahamian to AHEPA headquarters and introduced him to the organization’s executive secretary, George Leber, who arranged for them to visit AHEPA’s Cyprus committee, which was meeting at a nearby hotel. When they arrived, the ambassador of Cyprus, Nicos G. Dimitriou, was speaking, and he left the impression that Archbishop Iakovos was the head of the Cyprus relief program in the United States. A number of AHEPA members took exception to this interpretation, explaining that the church had played a very limited role in Greek war relief during World War II. “Iakovos seems to think he is an ethnarch,” wrote Saloutos, “and more or less operates as such.” Former supreme president John Plumides, who served on both the AHEPA committee and the Archdiocesan Council, was not clear on the dividing line between their different spheres of activity.38

Finally, Saloutos introduced Abrahamian to the committee. He had earlier mentioned to Rossides that it would be a good idea to join with the Armenians in commemorating the upcoming sixtieth anniversary of the Armenian genocide of 1915. The Cyprus committee voted unanimously in favor of this recommendation. Saloutos then spoke individually with some committee members about happenings on the West Coast and the role of actor Telly Savalas in supporting their cause. Saloutos was very satisfied with the day’s work.

On September 15 Saloutos was pleased to read two editorials that were favorable to Cyprus in leading newspapers, one in the New York Times and the other in the Washington Post. Another brief visit to AHEPA headquarters brought more criticism of Iakovos’s attempt to take command of Cyprus relief. AHEPA would not disband its efforts to follow the archbishop.

After almost a week in Washington, Saloutos traveled to New York City on September 16, where he discovered a number of groups willing to aid Cyprus. He talked at length with representatives of the Emergency Food Aid Committee for Cyprus at Cyprus House; they were collecting and shipping food and clothing under the auspices of the seventeen clubs of the Cyprus Federation of America, founded in 1951. They too expressed strong suspicions of Iakovos, noting that the archbishop “had never displayed great concern over Cyprus in the past. Why now?” They also questioned whether sending relief funds to the Cypriot embassy in Washington was a good idea. They wondered aloud whether such donations went to refugees or toward the operating costs of the government of Cyprus. On his last day in New York, Saloutos visited the Cyprus mission to the United Nations.39

This trip provided Saloutos with ideas about how his committee in Los Angeles could best contribute to the relief effort. He returned to California well informed about the various movements—and tensions—within the Greek American communities on the East Coast.

Congress Becomes Engaged

During the brief hiatus between the two Turkish incursions (July 20–August 14), Congressman Brademas focused more intently on the crisis. He continued his frequent contacts with Iakovos. At a State Department meeting on August 2, he expressed his deep concern to Undersecretary Sisco about Turkish troops on Cyprus and later introduced a resolution in the House urging the immediate withdrawal of foreign troops, both Turkish and Greek, from Cyprus. He and his four Greek American colleagues considered introducing an amendment to the foreign aid bill that would cut off aid to Turkey unless it removed its troops from the island. He knew the State Department would not be pleased, but Senator Walter Mondale had already proposed an amendment aimed at doing the same thing owing to Turkey’s decision on the opium poppy. Reasoned Brademas, “An amendment to cut off aid to Turkey given the opium and troop build-up on Cyprus might well be successful.”40

On the day of the second attack, the five Greek American congressmen sent a letter to their House colleagues urging them to support a resolution to cut off aid to Turkey. Here, a new argument began to emerge. “It is an outrage,” they stated, “that American taxpayers should be supplying arms to Turkey that are used in attacks upon a friendly country in violation of NATO commitments.”41 This view would become the basis for a broad legalistic and persuasive argument capable of attracting widespread bipartisan support in Congress. Arms agreements forbade the use of weapons in such a manner and prescribed an arms cutoff in the event of a violation. Turkey was therefore breaking the law, and the administration must punish Ankara as the law stipulated. Coming on the heels of the Watergate scandal and the chief executive’s bold violation of the law, this argument resonated with members of Congress. They were being called on to defend the basic principle of upholding the law—a principle for which they had struggled in recent months. If they failed to act now, all they had achieved could be lost. This approach lifted the debate from a narrow ethnic concern to a legal imperative. Also in play were humanitarian concerns for the displaced Cypriots, which coincided with rising support in Congress for human rights in general, an issue that received a cold reception from the secretary of state. This combination of principles would surely attract the interest and support of most members of Congress.42

Cartoon published in the Denver Post, October 16, 1974, showing President Ford fondly cradling a diminutive Turkish pasha wielding a bloody sword and a hypodermic needle. (©2019 Patrick Oliphant/Artists Rights Society, New York)

The day after the attack, the five congressmen met with Kissinger and his senior staff to discuss the situation on Cyprus and US policy to address the crisis. The secretary tried to put a good face on developments, arguing that, in hindsight, the United States might have done things differently, but “anything constructive that had developed during the crisis in Cyprus had been the result of US pressure.” Brademas, the most senior of the five, attacked the State Department’s failure to speak out at key moments about the coup, the Turkish invasion, or the Geneva talks. The United States, he claimed, had remained virtually silent. They were not blaming President Ford, he told Kissinger, “but rather … we place the blame squarely on you, sir.” Private diplomacy had failed, and they expected an end to US military sales and grants to Turkey until its armed forces left the island. Kissinger indicated that he could live with a sense-of-Congress resolution but not with any kind of mandate. He did not want to take action that would “mortgage our long-term relations with the Turks.” He favored a cantonal arrangement for Cyprus. Brademas ended by assuring Kissinger that he and his colleagues were not acting out of any sense of ethnic chauvinism.43

In this one long meeting, the two sides set out their basic arguments, which they would repeat many times over the following months. Kissinger knew that Brademas was a skillful tactician and fully conversant with the legislative intricacies of the House of Representatives. Brademas had served in Congress for fifteen years and would soon become the Democratic majority whip; he was thought to aspire to an even higher position in the House hierarchy. In fact, on another occasion, Kissinger would say to Brademas, “They tell me that one day you will be Speaker. Help me now with the new members of the House.” The secretary knew he could not trifle with the Indiana congressman.44

As protests large and small unfolded across the country, embargo forces were organizing in both houses of Congress. Theirs was no easy task because they faced intense pressure from the White House, which warned of dire consequences to US-Turkish relations should an arms cutoff be mandated. Nevertheless, new champions of censure arose in both the House and the Senate, and they were not Greek Americans; thus, they were unlikely to be accused of pursuing parochial interests. In the House, Benjamin Rosenthal (D-NY), a senior member of the Foreign Affairs Committee, became a leading spokesman for the embargo, based on the principle that the invasion violated American law. He and Pierre DuPont (R-DE) introduced an amendment to the continuing appropriations bill that would suspend aid to Turkey until the president certified that a satisfactory agreement had been reached regarding military forces on Cyprus. On September 24 the House passed the amendment by a vote of 306 to 90. But that was far from the end of the legislative battle. Over the next three weeks, Rosenthal was in the forefront of successful attempts to reject weaker Senate language and to respond to two presidential vetoes. Success came at last on October 17. Paul Sarbanes (D-MD), another strong supporter of the amendment, had feared that a failure to override the veto might cost them the whole battle; he sensed that the House was losing patience and that its members were eager to leave the capital for the fall recess.45

During these tense days, while the measure was making its way slowly through the House, Brademas attended a swearing-in ceremony in the White House Rose Garden, where he engaged in an impromptu conversation with President Ford. The president teased Brademas for giving him a hard time. Brademas responded that he was only trying to help Ford obey the law. The congressman also told the president that, “quite frankly, we simply could not believe much of what Kissinger told us.”46

In the Senate, Thomas Eagleton (D-MO) became the fourth member of the so-called Gang of Four, joining Brademas, Sarbanes, and Rosenthal. Eagleton had gained public attention in 1972 when Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern chose him as his running mate and then quickly dropped him from the ticket when he learned that Eagleton had received psychiatric treatment for depression. Brian Atwood, the senator’s senior adviser on foreign policy and defense issues, believed the incident had only enhanced his influence in Congress, making him a national figure. “He was probably the most sane person in the US Senate,” remarked Atwood. After his rejection by McGovern, Eagleton turned his attention back to Capitol Hill, where he continued to oppose the Vietnam War and the so-called imperial presidency.47

Atwood had recently met with a young State Department lawyer who revealed that he had written a brief for the secretary of state concerning the legality of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. The lawyer had concluded that Turkey violated its agreement when it used American weapons offensively. His report had been shelved on the advice of Kissinger’s former personal lawyer and current State Department counselor Carlisle Maw. Troubled by this information, Atwood wrote a speech for Senator Eagleton that took a cautious line, indicating that “unnamed bureaucrats were not informing the president of his legal responsibilities…. That got front-page headlines in the [Washington] Post and the New York Times. It was really big because the press had already been asking about it [the legal question]. Eagleton’s speech gave everybody on that side of the issue a boost.”48

Atwood became worried, however, about the growing tension between Congress and the executive branch. As a former diplomat, he was also concerned about the harmful effect of a cutoff on US-Turkish relations. With Eagleton’s permission, Atwood met with Maw and “suggested to him that if State could indeed get something going on the diplomatic front, perhaps through the UN, perhaps just directly, to get the Turks to agree to come to the table to talk about the issue, then they could legitimately ask the Congress to hold off.” He got nowhere.49

Later, Kissinger called Senate majority leader Mike Mansfield (D-MT) and asked whether there were going to be any problems with this issue. Surprisingly, Mansfield reportedly said, “I don’t think you’ll have a problem as far as I know but why don’t you come down to the Senate and you can address the Democratic caucus, and we’ll see.” So Kissinger made arrangements to speak to each caucus separately.50

When the secretary of state met with the Senate Democratic caucus on September 19, he faced considerable hostility. Eagleton questioned him about the State Department’s legal memorandum “claiming [that] Turkey’s August actions could not be legally justified.” Kissinger acknowledged that his lawyers agreed with the senator but added that Eagleton did not understand “the foreign policy priorities.” The senator replied, “Mr. Secretary, you do not understand the rule of law.” This confrontation only a month after President Nixon’s resignation “shocked some senators and convinced them that Congress was compelled to take extraordinary measures.”51

Eagleton led the embargo campaign in the upper house during this time, making a number of powerful speeches. He reminded his fellow senators of recent events. “We have just emerged from a trying period of American history,” he remarked, “a period when laws were winked at and rationalized to fit the concepts of policymakers. By and large, we have learned that policies created in ignorance or in spite of the law are doomed to failure.” And in response to the secretary of state’s concerns, he argued, “We are told to ignore the law, we are told that Henry [Kissinger] does not like the law; that Henry will have his hands tied, just as Henry said we would tie his hands if we terminated the Cambodian bombing … our distinguished Secretary of State is famous for his tilts. He tilts toward the junta in Chile. He tilts toward Thieu in Vietnam. His most famous tilt was the pro-Pakistan tilt. His current tilt, his Turkey tilt, is no wiser than the other tilts.”52

At first, Eagleton seemed to be acting on his own, without any input from concerned members in the House of Representatives. On September 9 he sent a letter to his Senate colleagues, asking them to support a sense-of-the-Senate resolution he had introduced three days earlier. He reminded them that in 1964 LBJ had warned Prime Minister Inonu that using American weapons to intervene in Cyprus would violate the bilateral agreement on military assistance and sales to Turkey. Now there could be no doubt that Turkey had crossed that line, and US policy must hold the Turks to account. This resolution passed the Senate with strong bipartisan support (64–27) on the same day that Kissinger met with the Democratic caucus.

Eagleton returned later that month with a much stronger proposition, demanding a cutoff of all military aid to Turkey. By this time, the leading pro-embargo congressmen and the senator and their staffs had met to coordinate strategy. The administration gave insufficient attention to this significant development, as it was rare for members of the two chambers to work together so closely.