Читать книгу The Green Box - James F. Murphy Jr. - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеOn up Pearl Street past Stretch’s house, the Flanagan house, a right on Jewett past the lamp post where I clocked thousands of hours in the rain, sun and snow, driving for the hoop with one eye on the curbstone and the other on the lace of the mesh. Left on Gardner—my street—down the steep hill where sleds had flashed in the winter night, a great ride all the way to the Park beyond and a slight rise, then bang, another hill that on good ice-snow could bring you to the other side of the Park.

The Park. Why had it suddenly occurred to me almost at the instant that I turned fifty that the Park could answer all the questions that had been mounting in me since my life began its slow, but perceptible movement to age. And even more, why and how could the Green Box answer any of those questions? Was this just a carry-over from some dramatic scene of a distant movie—Robert Taylor standing in the London mist of Waterloo Bridge, flashing back to Vivian Leigh? Was I living a scenario I wanted to write? I didn’t know as I parked the car and descended the cement steps that had replaced the green tufts of sweet grass of my youth.

It was a Saturday, a little before nine and early May. The wind stirred the winter leaves that clung and hung in the corners of the Park. The morning was overcast with the hint of rain. Not a good park day. Did I say that or had I said that a hundred times in my youth when rain was the great disappointment in childhood—at least in the forties when I was growing up?

The iron gate was lower than I expected but that was no great revelation. That observation of childhood objects diminishing in size the older we become had been made countless times by poets and novelists.

I looked out on the scarred and bald playing surface. There was deterioration, a ragged, unkempt and uncared for disregard for grass and soil and fences and tennis nets that hung like wet, heavy, gray figures in the cracked clay of the courts. The swings - the high-flying, trapeze-like swings were twisted and coiled about the long iron pipes.

I could still see Dapper Lonegan, slicked-back hair, the dandy of the Park, pumping his legs as he committed the worst sin of the summer—standing up on the swings. Legs bent, he gripped the iron chains with both hands, thrust forward, then swung back, pumping again like a skier. When he was up with the birds he stood straight as the trees. Up there Dapper owned that dizzying world and he was not coming down, even when Miss Feeney called Dusty Dowd, the Irish cop who walked his beat; a rolling barrel of a man with a roast beef face whose one great pronouncement from his few years of police work and the study of criminology was, “Get along or I’ll give you a swift kick in the arse,” as the roast beef was turning rare.

Dapper kept pumping and daring those laws of man and science as we, earthbound and helpless, looked up at him as he climbed higher, so much higher that it seemed any moment he would flip over the bars and continue somersaulting, turning horribly over and over until he was wrapped around the very bar itself.

“Sit down on the swings,” Miss Feeney bellowed the one automatic, categorical law of summer. There was no introductory remark, no “Please,” or “Be careful,” or “Dapper, you could hurt yourself,” it was simply the command of all park instructors who yelled it with hands cupped over the mouth from one end of Newton to the other. “Sit down on the swings,” plural as it was, Dapper now ruled only one.

The pumping continued as Dapper peered straight ahead into the clouds. The yelling continued; “Sit down,” Dusty repeated; the arse was now kicked swiftly a dozen times, and the quiet from Dapper’s peers accentuated the squeaking of the chains and the groaning of Dapper’s wooden trapeze platform.

And then as if controlled by some unseen force the speed diminished as Dapper ceased pumping. He slowly came to a halt but not a complete one because just before Dusty Dowd could grab onto The Park’s Flying Wallenda, Dapper pumped one more time, carrying him far out to the grass where he jumped, landing paratrooper style, and raced off up the hill to Gardner Street with Dusty Dowd yelling after him, “I’ll give you a swift kick in the arse,” adding under his breath, “when I catch you.”

Miss Feeney, tanned and stocky, just shook her head as we broke up and headed off to our summer pursuits.

The next year when I was in the ninth grade, I had been playing basketball at the field house next to the Park and was taking a shower while trying to hide the bones and the rib cage of my skinny body in the afternoon shadows that were stretching across through the one, low window, when I heard a voice say, “Miss Feeney died.” A naked figure strode confidently into the shower. “That was too bad.” It was Phil Poirier. I never liked him. He was cocky and his jokes were always at someone else’s expense. I was waiting for him to call me “Bones” or “Frank Sinatra” so when he said, “Miss Feeney died,” it didn’t register at first. Then, the realization slowly dawned on me. Miss Feeney dead. And Phil Poirier even cared. That surprised me, from him, the towel flicker. Right smack across the buttocks. He was a real snapper. Flick! Crack! Ouch! I looked at him. He actually cared. He never seemed to care for anybody. Most of the time he played cards at the Park, sitting with legs spread out over the long, narrow benches, throwing cards down and saying movie stuff like “I’ll never raise you, “or “I’ll see you for a dime.”

So I was surprised when he said it was too bad. I liked Miss Feeney. She was kind and she talked to kids as though they were her equal. My eyes filled up with tears and I wanted to cry, to sob, to yell out how sorry I was. I soaped my face so my eyes would be bloodshot from the stinging soap. I turned up the shower so my voice wouldn’t sound as though it was cracking. “How, how did she die?” I yelled over the din of the showers.

“Cancer,” he said with authority.

Cancer. It was a word that was generally whispered and to hear it yelled over the noise of the shower made it seem even more sinister, like something that everybody got eventually and there was no escaping it, like polio or pneumonia. I would never reach age twenty. I knew that then, when Poirier, almost casually accepting said “Cancer.”

“Yeah,” Poirier continued, “She was O.K.”

“Yes, she was,” I agreed, trying to control myself.

“Yeah,” he repeated as he soaped down, “She was O.K. and she had a real nice pair of knockers.”

On the night that Poirier told me about Miss Feeney, I walked home by myself. I didn’t know much about death although with World War II exploding daily in the newspapers and boys from the neighborhood, who only a few years before were playing in the Park and no doubt standing up on the swings, dying in strange places, death was slowly no longer a stranger.

Joe McCarey, who led “The Men of Music,” was one of the first to die and my mother used to point at the McCarey’s window for years afterward and say of the square, satin flag that hung red, white and blue from the curtain tassel, “That’s all the poor woman has, a Gold Star to show for all the pain of bringing a child into the world.”

But that was different, Joe McCarey’s death; it was heroic and the way any one of us would want to die—rushing a machine gun nest like Gary Cooper in Sergeant York. But not the way Miss Feeney died, from some disease that couldn’t be seen and just blew in on you for no reason and from nowhere in particular. These thoughts occupied me all the way home, my corduroy pants whistling as I sloshed through dirty snow. The field house, an annex of the elementary school, was quiet and in darkness as I passed it. I thought of the afternoons we played half court three on three, and Saturday mornings when Miss Feeney opened up the annex early so we could glut ourselves on basketball all day long.

I didn’t feel like going home. My father would have eaten and already gone off to his night job in the liquor store and my sister was always somewhere else, but that was a small loss because I never really knew her anyway. My mother was working in the war plant so supper would be on the back of the stove. I could eat any time.

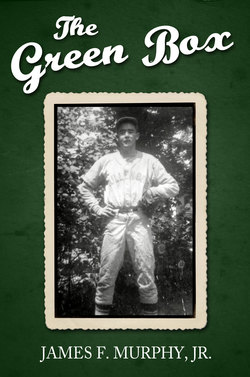

I walked through the iron gate and sort of moseyed through the Park until I got to the Green Box. I always wondered if all the summer stuff was kept in it during winter. I tried to lift the cover but it was secured by a strong lock. I thought of all the times Miss Feeney opened the Box for us, and we reached in for the gear that was special to us and us alone. Stretch Magni always grabbed the catcher’s mitt and the mask, shin guards and chest protector. Larry Finerty and his brother, Little John, always took the cards and the comic books.

I used to trade comic books with their father. If my mother wasn’t working the night shift, I’d say after supper, “Ma, I’ll be right back. I’m just going over to Mr. Finerty’s to trade.”

Mr. Finerty, who worked hard and drank harder, would be sitting in a clean white T-shirt on the steps of the porch reading funny books and drinking beer. Larry and Little John would be arguing over cards and I would approach in a very businesslike fashion. “Hi, Mr. Finerty. I was wondering if you wanted to trade.”

“Sure, Sull, whaddya got?”

Looking at the pile in my hand, I’d select one and show him. “New Wonder Woman—full cover.”

“Yeah, yeah, looks good. I don’t have that one. What’s the deal?”

“Three covers for this one.”

“Two.”

“O.K., two.” I was always quick to oblige. I didn’t like to argue and I still made a good deal—two for me.

“I got a Crimebuster and a Batman—no covers—O.K.?”

“O.K. Thanks, Mr. Finerty.”

When we made the swap I could always smell beer or booze from him. But, he was always friendly and respectful.

“You’re a good businessman, Mr. Sullivan,” he’d say with a twinkle in his red eyes.

“Thank you, Mr. Finerty. See ya next week.”

I climbed up on the Green Box and sat in the brittle March cold, shivering and thinking about what Miss Feeney’s death would mean to all of us. I began to cry and shake and I was really going at it when I heard a voice from the benches back near the fence. “Hey, kid, what’s wrong?”

I froze in shock and fear at this voice out of the black. “Huh? Wha—what?”

The figure rose from the bench and approached me and then I breathed a sigh of relief when I saw it was “The Jugger”—Jugger Casey.

“Hey, Sully, that you? That the old Sully sittin’ there cryin’ his eyes out? What ya cryin’ about, Sull?”

He was holding a wine bottle by the neck, dangling it playfully. I could hear the wine swishing around inside the bottle. He used his thumb as a bottle cap. He handed me the bottle and I took it, not knowing why he did and why I did. He hoisted himself up on the Green Box and took the bottle from me, gulping in a mouthful and placing it between us. “I don’t think you want a swig of wine, do ya, Sully?”

“Yeah. I do,” I said resolutely. In the movies people always drank when they were sad or depressed.

“Well, help yourself. I’ve got another bottle stashed behind the fence.”

I took the bottle and gulped down the wine. I had never had it before, and I was surprised by its sweetness. I liked it.

“So, Sully, what ya cryin’ for?”

“Oh, I was just sad. Miss Feeney died. Didja know her, Jugger?”

“Sure, I knew her. I used to watch her from my bedroom window. Nothin’ dirty, mind ya. I just thought she was good with the kids.”

Jugger was around thirty years old and he never had much schooling. He lived with his parents who seldom came out of the old, brown house that brooded over the Park. My father used to say he had been a very good baseball player, had played in the Industrial League. One night he was pitching for the Rope Mill and a giant French Canadian down from New Brunswick, who was clowning around, was impressed with his own brand of humor. My father and his friends told the story many times while they were pitching horseshoes at The Park after supper. And they told it with that Northwoods accent—all of them—and they all told it well.

“The game was in the fourth inning with the bases loaded when the Frenchman, he come up to de plate. Ball one, ball two, ball three, ball four. The Frenchman, he look here and he look dare and he say to de crowd, ‘Hey, the bases, she are full, wherrr shall I go?’ The crowd broke up and the giant strode to first. Jugger was not pleased. The game meant a lot to him because there were Major League scouts in the stands and Jugger, who couldn’t do much in life, but could burn a baseball, knew that was his ticket to a good life. He settled down and struck out the side.”

My father and his pals always added how “the Jugger’s” grin lit up the ballpark. “They could have played a night game by that grin,” my father said.

The game progressed and The Saxony Mills Team—Jugger’s team—took a seven to one lead going into the ninth inning. The scouts were standing behind the backstop now, scrutinizing every pitch and Jugger was not disappointing them. The catcher’s mitt was puffing smoke and every pitch brought “oh’s and ah’s” from the crowd.

The giant lumberman got up to bat again. Jugger had made him look bad all afternoon and the Frenchman’s bravado had greatly diminished.

Just as Jugger was about to throw, the Canadian stepped out of the box and began pointing with his bat to second base. His great bulk was bent over with laughter. All eyes turned to second base to see a dog squatting on the bag and then chased off by the second baseman’s flailing glove.

The Frenchman took center stage again and he turned to the crowd and announced, “Well, one thing is cer-tane—whoeverrr gets sec-ond gets turd.”

The crowd roared its approval, laughing, screaming, the echoes of laughter washing over the crowd, the players and the ball field. Everyone roared and applauded gleefully, everyone except the Jugger, who was one out away from a Major League contract. He could feel it, he could taste it. He was about to be somebody and this Frog out of some two-bit lumber town was turning his moment of glory into mockery. Even the rival scouts were thumping each other on the shoulders now in jovial camaraderie.

Jugger rubbed the ball until he almost rubbed the threads off it.

“C’mon, you Frog. Save your act for vaudeville. This is baseball.”

The giant stopped in his tracks, glued to the grass. The stands quieted down. “What did he say? What did the Jugger call him?” ‘Frog’ passed from aisle to aisle and on out to the standing spectators behind the ropes in left field and right.

“Hey, picture man. What you call me?” The brown eyes narrowed and the Frenchman’s grip tightened around the bat. Veins stuck out like cords in his neck. “Frog,” Jugger said. “Play ball, Frog.”

Now the afternoon was muffled as though someone had thrown a blanket over the entire field and spectators.

The Frenchman began a slow, deliberate walk in the direction of the pitcher’s mound. He held the bat like a toothpick in his powerful right hand.

The Jugger backed up, and the Frenchman kept coming. The plate umpire ran after him and tried to hold him back. The Frenchman swatted him with his left forearm, knocking him to the ground as he gained the rubber.

“Frog, eh?” and he threw a punch at Jugger, who tried to block it by putting his pitching hand in front of his face. The fist drove on through to the face. There was a sickening sound of bone snapping like a branch, and Jugger toppled to the ground. His face turned pale and he was too weak to get out of the way of the bat that smashed against his head and outstretched arms.

The Jugger never threw a baseball again. The arm never responded to surgery and it hung crooked all his life. The skull fracture dimmed his vision and caused his thinking to slip a few beats. Sometimes, he spoke slowly and slurred his words.

The Frenchman was to be tried for assault, but he made a run for the border and was never seen again.

“I’m sorry you’re sad, Sully. You shouldn’t have to be sad. Kids should never be sad. Things happen in life. That’s what my father says. It’s the way God wants things. We can’t always know why these things happen, my father says, but they just do. Like accidents. So don’t be sad, Sully. You’re just a kid. I don’t ever like to see kids sad. I was watching from my window one day and I saw Mr. Callahan come into the Park looking for his kids. When they saw him coming they started running away and he was stumbling and staggering and swearing at them. He yelled at them to stop and the little girl, the pretty little one with the curly, black hair, how old isshee, Sully?” he slurred.

“Oh, I dunno. Maybe nine?”

“Well, she stopped and came back even though her brothers kept yelling at her to get away. Mr. Callahan’s face was red as a beet, Sully, and he hauls off and whacks her right across the face three or four times. Oh, Sully, I was so sad when I saw that. I wanted to go down to the Park and kill him. But I didn’t do anything because my father sent me to my room for drinking too much wine.” He laughed a high-pitched, giddy laugh. “That’s why I drink down here and hide my bottles. Once I’m drunk there’s nothing he can do about it. Sometimes I sleep it off on the bench and sneak in the house before the sun comes up. Hey, you know a real funny thing? I took Miss Feeney’s key once and had a set made by Willie Shapiro up at the Lake. You know some nights when it’s real cold I sleep in this Box. I just prop up the cover to get a little air and I have my wine and I lie there thinking about the old days.

“You know, Sully, I can lie right here in this Box and look up at my house. I watch my father’s shadow in the parlor, walking up and down, up and down, until he gets tired of waiting for me and he goes to bed. That’s a nice feeling for me, Sully. I put one over on him. Do you know what I mean, Sully? Have some more wine.”

“Yeah, I know what you mean, Jugger. Thanks.” I swallowed off another mouthful and I was feeling a little heady.

“That will make you feel better, Sull. It kind of covers the pain. It always does for me. You’re not sad now are you, Sull?”

“No, I feel better, Jugger. I guess Miss Feeney’s dying is just one of those accidents like your father said.”

The word father was like pressing an alarm button as the cracked, cackle of a voice cut through the high grass and bushes of Jugger’s backyard and tripped on down the hill and over the fence to the Park where we sat huddled on the Green Box.

“Francis. Fran-Cis. Frannncis.” The paper-thin cackle roamed the night.

“Ssssssh, don’t say anything. Just stay still, Sully. That’s my father. He wants me home. But I’m not going home. I’ve got plenty of wine and I’m going to sleep in the Box for a while and look up at the stars. That’s when I have my best dreams.”

“Francis. Fran-Cis. Frannncis.” The eerie cadence continued hovering first over the Park and then drifting off in the night as the back door of Jugger’s house slammed shut.

“He’s gone.”

“Yeah. Well, thanks for the wine and the talk, Jug. I really appreciate it. I feel better.”

“Do ya, Sull?”

“Honest. I really do.”

“Good. Sull, you won’t tell anybody about the keys and the wine and the Green Box will ya?”

“Course not, Jug. That’s our secret. Between us. Shake.” And we shook hands on something that was ours and nobody else’s, and knowing that made me feel good.