Читать книгу The Green Box - James F. Murphy Jr. - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER THREE

ОглавлениеThe war was no longer being fought on the back lot of Warner Brothers or Paramount. And it was becoming more than “The Movietone News” we saw twice a week as Stretch got taller, and the break-ins to the theater included, sometimes, a dozen kids. We sat there, cheering and thumping the leather cushions, as U-Boats, munitions factories, cities, and airfields blew into pieces and aircraft—German and Japanese—exploded in mid-air and plummeted into the North Atlantic or the Pacific Ocean. Tracer bullets directed us from belly gunner to target, sandwiched between the two movies—Cagney killed and danced—and Veronica Lake squinted behind a curtain of silken, blond hair that covered one side of her face. Dana Andrews was captured by the Japanese and tortured in Tokyo, while Bing Crosby and Risё Stevens tried to save the souls of young boys through songs and baseball. Barry Fitzgerald narrowed his eyes and cocked his head to all of it.

Our immediate battleground was the Park, Gardner, Pearl, Jewett and Fayette Streets. My father and quiet but friendly Mr. Morton, who lived on Jewett across the street from my Park friends—the McQueeney boys—became air raid wardens. At night I would kneel by the parlor window with my heart pounding as my father dared the black veil of night. Mr. Morton would inch over the dark streets, crouching behind bush and tree and lamppost until he would appear halfway down Gardner Street hill and slip up, commando style, behind my father, who was carrying a fire extinguisher in watchful anticipation of German bombers. No one ever really told us that there would have been a fuel problem somewhere across the Atlantic so we all waited to be featured in Movietone News the following week.

My father and Mr. Morton, helmeted and intrepid, patrolled our street, yelling to an errant neighbor to shut the light off and tuck in the black window covering. “Don’t you know there’s a war on?” Mr. Morton would chide. My father, gentle and kind by nature, would just shift, embarrassed, from one foot to another.

The blackout secure, my father would come in at eleven o’clock, his military tour over for another night and we would have hot chocolate. My father, who never swore, would say to my mother, “Gor-ram-it, Rose, Charlie Morton is a great guy until he puts that helmet on and then he thinks he’s George Patton. Gor-ram-it, it’s embarrassing.”

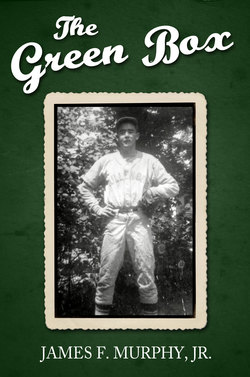

One day as I stood by the Green Box waiting for Miss Feeney to open it and pass out the cards and board game to the gamblers, and the baseball gear to the rest of us, I looked up to the sidewalk beside Jugger Casey’s house. My mother was standing there talking to Bessie O’Leary, who we were all convinced was a real, live witch. My mother was dabbing at her eyes with a blue apron. I froze for a moment. Who was dead or hurt? My father – I knew it was my father. He had a heart attack. Oh, God, why? Why did my father have to die? I felt sick and numb as I passed the catcher’s mask to Stretch and ran up the hill to my mother, who was discreetly blowing her nose into the apron.

“Bill, we’ve had some bad news. Your cousin Jackie has been killed in action. On Saipan. My sister’s boy,” my mother said, as she turned back to the witch.

I had never seen Bessie this close up before. Most of the time she was looking out her windows, the curtains pulled back just enough so she could see us, and we could see her. I backed away, more intent on Bessie O’Leary than on my cousin Jackie’s death.

“Yes,” my mother went on, “my sister died when he was only a three year old. That’s when the father went sour. We don’t know where he is. Bill, go get your bike and ride over to Nana’s house. Your cousin Evelyn called to tell me. Her aunts in Brighton got the telegram this morning. They brought him up,” she said to the witch.

“What do you want me to do, Ma?”

“Just be with her. Just console her.”

I ran up Gardner Street, past Bessie’s house. Then I stopped and ran back through her yard and climbed over the stone wall. None of us dared go through her yard but since I knew she wasn’t home I had nothing to fear.

I always felt foolish riding the bike. It was my sister’s and it didn’t have a bar. I never knew why girls’ bikes were different, but I reluctantly jumped on and raced past my mother who was laughing at something. I did not understand how she could laugh when Jackie was dead in a faraway land.

The war had always been in movies or in the gold stars that hung in the shadows of dark houses, but now it seemed closer to me. To our family. To the Street. To the Park.

My girl’s bike was a P.38 fighter plane and I mowed down Jap soldiers all the way to my grandmother’s while I repeated the strange sounding place in the South Pacific where my cousin, who always smiled and had a million freckles, now lay still—forever. Saipan, Saipan, Saipan, I whispered as I hovered over the handlebars. I turned into Nana’s yard just as Evelyn was walking up the dirt path.

I had a lump in my throat and I didn’t know what I was supposed to say. Nana had been dead two years. Aunt Louise, my mother’s sister, was still at work in the telephone company, so that left me all alone. “Console Evelyn,” my mother said. Why didn’t my mother console her?

“Ev? Ev,” I repeated as I ditched my bike in the dirt.

She turned to me with the crumpled telegram clutched in her hand. She didn’t say a word as I approached her. Tears streamed down her pretty face. I couldn’t speak. I just put my arms around her and told her how bad I felt.

The war was no longer out there, far away, as other cousins were wounded, even Evelyn’s older brother, Bobby.

It was June 1944 when we received word of Jackie’s death and by August of that summer, because many of the kids in the Park lost relatives on D-Day in Europe or on the Pacific Islands, we would spread the newspaper out on the top of the Green Box and read about Normandy, St. Lo, Marseilles, Belgium, The Ruhr Valley, and the other war—Burma, Peleliu, Bloody Ridge. The headlines bannered names like Patton, Montgomery, Vinegar Joe Stillwell, Merrill’s Marauders, Rommel, Eisenhower, and MacArthur, as baseball and summer continued to roam the Park without interruption. It was as though the movies and the real war were one and the same. And when we thought about the battles and the beachheads, it was with the idea that once victory was established, the credits would appear at the bottom of the front page. Directed by Michael Curtiz or King Vidor. Art Director: Hans Drier—Cedric Gibbons. Screenplay: Dwight D. Eisenhower. Removed from it all, we almost enjoyed the war as news and pictures and conversations buzzed, always just a few feet away from us across kitchen tables or behind radio static, or from an offhand observation of my father’s after supper as I’d be heading out the door.

“Where you headed, Bill?”

“Park.”

“Enjoy it. It’s later than you think.” He’d wink and smile. But sometimes I thought there was a sadness in the remark. Then he’d smile again and sing.

“Enjoy yourself. It’s later than you think.

Enjoy yourself, while you’re still in the pink.

The years go by as quickly as a wink.

Enjoy yourself, enjoy yourself, it’s later than you think.”

I’d go off down to the Park, humming, leaving my mother playing the piano and my father singing along to her the song of the day.

“Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition and we’ll all stay free.”

And then crooning into,

“It seems to me I’ve heard that song before.

It’s from an old familiar score.”

My father’s big song that year, one that he “Crosbied” from the parlor through the open windows and trilled along the sidewalk as I made for the Park, was,

“I had the craziest dream—last night, yes I did I never dreamt it could be—yet, there you were in love with me.”

The Park after supper was a new and different experience than the hot sunny daytime of twenty inning baseball games and marathon appearances of Dapper Lonegan on the high trapeze.

We would sit on the benches or on the Green Box, trading stories of the war or the Red Sox—and then the bats would come. They would mysteriously and subtly appear just as the last hazy glow of daylight slipped over the roof of Jugger’s house.

We would sit quietly, never moving a muscle, watching one, then two, and then a dozen maneuver and cruise above the Park. They dove, they fluttered with almost a banging sound. They speared skyward and they circled in black clusters. They always seemed to circle. The girls, who always sat in giggling groups near the tennis court, screamed as much for our attention as from the fright of seeing the mouse bodies and winged membranes cavorting and diving in our skies.

Short, high-pitched screeches sent electric shocks up our backs to the nape of our necks. One night Dapper Lonegan manned his flying platform to join the flapping bodies above our heads.

“What if they attack him?” Pepper Lucas said.

“They’ll tear him to pieces,” his younger brother, Fat, agreed.

“Good you’re not up there, Fat. They’d have Thanksgiving dinner on you.” Phil Poirier was always there to cut your legs out from under you. No one ever said anything though, because Poirier was strong and he could fight.

“Bats get in your hair and you’ve had it.” Charles Webber was smart. He read the Encyclopedia Britannica and he knew just about everything in the world. His father was dead and he and his mother lived up behind Bessie O’Leary’s house. He was the one who told us that she was a witch. No question. Absolutely. He saw her walking in the dark, around and around her backyard. She caught neighborhood cats and Webber used to hear them shrieking in pain at odd hours of the night.

“Most of us are O.K. because we have crew cuts. Not Dapper, though. They could probably build a nest in that hair of his.” And then Dapper, as though he heard the warning, or had the same radar the bats had, slowly descended and jumped out onto the grass and raced off.

“Now, those girls, if the bats ever got to them, they’d get all matted in those curls.” Charles Webber laughed sometimes as though he was slowly letting air out of a balloon.

The girls continued to scream and that was our signal to go over and scare them even more because that’s what they wanted.

“Let’s go,” Stretch said.

And we were off like a rebel band of Apache warriors, screaming into the night as the girls broke from the intimate security of their benches and ran out into the middle of the baseball diamond. This was pairing off time for most. A few of us, like me and Fat and Charlie Webber and Little John Mahoney, trotted half-heartedly after them.

When the phony wrestling and wagon train captures were complete, Stretch or Birdie Baker, the Mad Looper - who caddied every day, rain or shine as long as there was someone who wanted to swing a golf club - called for quiet.

“O.K., how about Hide and Seek?”

“Oh, yes. O.K.,” Margie Marini said.

“O.K. O.K. Stretch, you take half on your team and I’ll take the other half,” Birdie commanded.

“I want to be on your team, Birdie.” Margie Marini jumped up and down, her large, round breasts bouncing under her white T-shirt.

“Yeah, and we know why,” Stretch laughed. “Try and get back to the Green Box before morning.”

“You’re my first pick, Margie.” Birdie’s ego cracked his voice as he spoke.

Everybody fanned out with final instructions burning in their ears. Stretch’s team was “The Hiders” and Birdie’s “The Searchers.”

The Park was open territory except for the Watertown end where we never played anyway. There was an invisible line we all knew that separated Newton from Watertown.

“Stay away from the Watertown end unless you want to get the crap knocked out of you,” Stretch warned.

The Watertown end was for the older kids like Peggy Anderson, who was blond, with long legs sticking out of white short shorts and a chest that would make Margie Marini look like a boy. She always went down that end after supper and always with more than one guy. Four or five other couples joined them on the side of the green and lush hill and I always wondered what they did down there all that time. I used to get excited and hot and sweaty when I thought about it.

“O.K. You can use the Park and the Streets—all backyards except Jugger Casey’s and Bessie O’Leary’s.” Stretch laughed that head-rolling laugh. “Unless you want to join the missing cats. He, he, he, ha, ha.” His exaggerated, insane laughter sent chills up our spines as we took off, shouting and screaming into the night.

It seems I always was a Hider and I never knew where to hide. I remembered listening to “The Most Dangerous Game” on the radio where the internationally known big game hunter Rainsford is now being hunted by a General Zaroff. Rainsford’s plan was to get as much space between him and Zaroff because Zaroff wants to hunt and kill “The Most Dangerous Game-Man.”

So, in my mind I became Rainsford who was now discovering what the animal must feel when being tracked. I headed up by the Green Box and then I scaled the fence into Jugger’s backyard.

I crawled past an open bulkhead and stood motionless behind a fruit tree that smelled like cheap perfume. Somebody was coming up the cellar stairs just as I was about to make a run for it to Gardner Street. At first, I thought it was Jugger’s father but then I realized it was the old Jug himself. I was about to whisper to him that we were playing hide and seek but before I could, I heard him crying. Crying like me in the Park that night we sat on the Green Box and he let me have a few swigs of wine. And he said those things about accidents and how things just happened like his father said.

He was muttering something I couldn’t make out because he was crying so much. Then, he stopped and put a bottle to his mouth, drained it off and flipped it into the woods where the sound of glass on glass broke the silence. Below me in the Park I could hear some of the giddy girls squealing. Jugger picked up a rock, wound up and with his crooked arm sticking out sideways, he threw the stone into the same place in the woods. It landed softly. “You Frog, you son of a bitch, Frog. I wish I killed you. Frog. Frog. Frog.” His voice gained in volume until Mr. Casey opened the back door, the yellow light from the kitchen spilling out to the yard and washing over Jugger who stood glassy-eyed, shyly drawing back into the shadows.

“What? What in God’s little green acre do you have on? Come here. Come here to me, Francis. Come here this instant.”

The Jugger moved out of the dark silhouette of trees into a splash of light. His crooked arm hung guardedly over his jacket in a vain effort to cover it. As he moved forward, I could see that Jugger was wearing a World War I doughboy uniform, even down to the puttees. We had a picture of an American soldier in France that had been my uncle’s and The Jugger was dressed the same way, except for the baseball cap he always wore.

“Why in God’s name are you dressed in my uniform? Have you gone completely crazy? What possessed you to put it on? Answer me.”

“I dunno, Pa. I just wanted to.”

“You just wanted to? What kind of a reason is that?”

“Well, all the pictures in the paper.”

“What pictures? What paper? What are you talking about?”

“The War pictures. The soldiers. They all wear uniforms. I see them every day in The Boston Post and The Record. And, and those good ones in Life magazine. Those are the best, Pa.”

“Oh, Francis, you are the cross I have to carry. My only child and –” he paused. “Francis, you are not a soldier, you are not a baseball player anymore, you, you, you’re just my son. Come in the house and take off the uniform and do not drink any more wine. Your shouting woke up your mother.”

“I’m sorry, Pa. Honest. I’ll take off the uniform. But, can I still look at Life?”

“Ah, O.K., I suppose so. Please come in for the night.”

Mr. Casey closed the door, snuffing out the light as Jugger stumbled up the porch steps. “Frog bastard,” he shouted to the woods and then he went inside.

I let out a long, deep sigh. I felt almost sick. I had been part of something strange and kind of sad and scary at the same time and I didn’t know how to react at first. But, as my body unstiffened, I realized I better get out of there, so I raced through the high grass of the driveway and out onto the Street and on past my house.

My mother and father were really going strong now with

“You’ve got to ac-cent-tchu-ate the pos-i-tive,

E-lim-my-nate the neg-a-tive,

Latch on to the af-firm-a-tive,

Don’t mess with Mister-In-be-tween.”

I caught sight of a gang furtively sneaking up from the Park and I took off through my yard and over Leavit’s fence and double backed through Fagan’s, running like a wild horse, until before I realized it, Bessie O’Leary’s house materialized before me as though emerging from some inky, subterranean cave. One light burned from an upstairs room, the remainder of the house barely visible in the jet-black night.

A slight rustle of leaves from a silent maple brought my breath in short, rapid gasps. From the Street, sharp commands, quick and pointed from Birdie to his searchers, reached me as I crouched behind the Witch’s Wall. I knew they would never go into the Witch’s yard, but they could double back the way I did and come up behind me. So, I made the decision to jump the wall and sneak out behind them and race back to the Park and the Green Box. According to the rules, you had to stay out at least twenty minutes and I had already done that.

I took a short jump and bellied my way over the wall, slipping quietly to the ground. I waited until I knew they were halfway up the hill and then I picked my way through the dark past the clothesline where a white, linen gown or something, hung limply in a ghostly pose. I continued across the yard and then suddenly a cat cried, and was answered by the sound of other cats.

My eyes narrowed to the location of the sound. I was curious. I was insanely frightened, too, but I began walking to the rear of the old house. I was doing exactly what I warned others not to do in those Class B horror films, when in spite of the warnings from the first four rows of the Paramount, the hero began his long walk upstairs to the attic and whatever was lying in wait.

The cellar door was open and at the far end, the Street side of the cellar, a vague, blue bulb threw just enough light to make objects distinguishable. What manner of madness drove me on I could not explain to the thumping heart or throbbing brain that seemed the only parts of my body that were alive. I was always a reader, ever since I could pick the colors and the names of animals from the large print books my mother got from the children’s library, and now in Bessie O’Leary’s midnight black yard, I was a character out of Edgar Allen Poe, and I was in search of The Black Cat. I ducked under the low frame of the door and felt my way along the damp, fieldstone walls. Before me, cats of all sizes slept or crawled or pawed at each other as they collected in large pockets.

Charles Webber was right, but Webber had never walked through and around slinking, sloe-eyed cats. They lay in heaps on top of wooden S. S. Pierce boxes or in furry mounds on top of last winter’s ash heaps. Some peered out from the coal bin with yellow, jungle eyes as I stepped gingerly over them. Was I crazy? What was I doing here? My mouth was filled with cotton and sweat poured off my forehead. My armpits prickled. There must have been a hundred cats in that cellar and scattered all over the cement floor was corn meal that the cats picked at and then settled back into their individual colonies.

The cellar itself was stacked with newspapers that reached the ceiling, yellowed parchment that smelled of mildew and cat. Everywhere there were newspapers and cats. I walked several feet deeper into the cellar and then I could feel something near me almost touching me. I raised my eyes to a pile of newspapers directly in front of me, and there perched in unmoving black fur was a thick-chested, oval-bellied cat that sat with olive eyes fixing and piercing. I froze at the size of this cat that was almost as big as a small dog. My heart left my chest and disappeared somewhere down into my thighs.

The black cat, Poe’s Black Cat, I was convinced, began a hissing sound like gas escaping from a jet, and then a mournful, tormented, almost painful bawl, and then the hissing sound, followed again by the tortured cry.

I can’t remember how long I stood there, paralyzed. I just remember being slightly freed of my paralysis when I felt a hand on my shoulder and as I turned around I looked directly into the cracked and wrinkled face of Bessie O’Leary. The Witch. I stared into that face for three thousand years and then my eyes popped, while my whole body shook and trembled into action and I darted past her, tripping over screaming, squatting cats that scattered, frightened, in every direction, toppling over each other in a riot of confusion.

I raced so fast that I ran headlong into the white gown hanging out to dry. It was wet and clammy like a sweating body and I furiously tried to disentangle myself from it. When I finally succeeded, I didn’t know which direction to turn. It was as though Bessie O’Leary was everywhere. She was guarding The Witch’s Wall - her wall. She was at the front of the house. She was behind Margie McIntyre’s barn next door. She was on top of the roof of her own house, watching me, staring at me with powerful witch’s eyes.

A figure appeared at the cellar door and I plummeted off into deep bushes that bordered the path to Joe Cushing’s store. I burrowed down to unfathomed depths, covering and camouflaging myself with branches and leaves like the marines. I lay there, trying not to breathe. I waited for the sound of approaching footsteps but none could be heard. After a while I heard a door slam, and then an upstairs window squeak down the ropes and close. I looked up at Bessie O’Leary’s house. It was in darkness and the night was still.

Suddenly, I felt warm and shivery all over. I had done what nobody else had ever dared to do. I had gone directly into the bottomless pit of Hell, Bessie O’Leary’s cellar, and I saw the cats. I stood in front of the leader, the Big, Black Cat. And, Bessie O’Leary touched my shoulder and I looked right into her face and I would never forget those watery, red eyes of hers staring straight at me out of deep, sunken sockets. I had done something that Stretch or Birdie or Poirier never would have dared to do, and Charles Webber could only guess about. I would have them eating out of my hand at the Park.

I crawled out from under the branches and leaves and sat up in my forest den that kept the outside world away and was hidden by thick vines that were like prison bars—but I did not feel like a prisoner. I felt free in a quiet world that only I knew existed. Only two years before when I was twelve, I would climb a tree high above my house and sometimes I’d sit high on my perch, concealed in leafy shadows while I read James Fenimore Cooper, Albert Payson Terhune or my comic books. My mother would come out and call me, but I wouldn’t answer. After a while, she would give up, thinking I was at The Park and I would continue reading with the same air of feeling I was experiencing right now in the secret hollow of The Witch’s backyard.

I could hear the shouts in the night and the galloping feet of the Hiders and the Searchers racing back to the Green Box, either to win or lose. And through it all, I was lost to the world, a displaced person, a “D.P.” the newspapers called it. Nobody in the entire world knew where I was. It was one of those most exciting moments of my life. It must have been the way God felt. He could see and hear everything but we couldn’t see him.

I heard Birdie say, “Where’s Sully? Did he go home?”

“Sully wouldn’t go home. My gang knows the rules. If they go home they have to report to me. What the hell, if they didn’t we’d be out lookin’ for them all friggin’ night,” the “captured” Stretch whined. I knew the sound. It meant that Birdie’s gang was victorious again. It killed Stretch to lose.

“O.K.,” Birdie said, standing under the gold halo of the streetlight. “Who’s still out?”

I could see it all and hear it all and I thought I’d blow up, it felt so good.

Stretch looked around. “Webber, Doris, Betty Martin, Little John and Sully.”

“O.K., let’s fan out again. Be ready, Sully’s the type who’s like a rabbit. He’s so skinny he can slip right through you like grease.”

I felt my face burn and tears sting my eyes. I hated the word “skinny”. I used to go to bed at night praying that God would make me fat, so fat that I would waddle when I walked. I could never understand how some of the kids who were poorer than we were, and only drank Kool-Aid and ate Devil Dogs, could have muscles or be fat. We always had good food. Sure, it was great to be fast, to be able to slip through the evening like grease, but nobody in the world wanted to be skinny.

My inner sanctum didn’t seem so great any more and I was beginning to think about letting myself get caught, so I could go home to bed and dream about being fat and kids would call me Chubby or Porky Pig or just plain Fatso. I lay there thinking of names: Whopper, Lumpy, Heap, Jelly Roll, Puffy, The Barrel, Drum, or Cannon Ball. Any one of those was better than Skinny or The Thermometer, or as a guy who came through the Park once in a while used to yell at me, “Hey, Superman.” I was always afraid a name would stick, that’s why I’d stay away from the Park for a while or go up to Rats Alley to see George and Ralph, because they didn’t seem to care about what you looked like. They were young like me, but even then I knew that they were old.

I knew it was getting late and I figured I might as well go home. I’d break the rules for tonight and maybe that would be O.K., too. Maybe they’d wonder why I just took off. Maybe they might even realize that I heard them.

My thoughts were interrupted by the sound of footsteps coming up the path from Joe Cushing’s store. I sat rigid and breathless, letting the air pass through my nose. The footsteps were soft, but they were coming closer. I knelt forward, peering through an opening in the hedges. Now, I could reach out and grab the leg of this prowler if I had the courage. I looked up at the face that was barely visible from a shred of light from the Street lamp and realized it was Betty Martin. She was on my team and she was alone.

“Betty,” I whispered hoarsely. “Betty, are you still out?”

“What? Who is that?” She stopped dead in her tracks.

“Sully. I’m in here.”

“Sully? Are you still out, too?”

“Yeah. Come on in and hide. We’ll make plans.”

“But that’s Bessie O’Leary’s.”

“Don’t worry about her,” I said bravely. “She’s taken care of for the night.” Still, I looked back to the darkened house to be certain. The upstairs window where the light had burned was now a square frame of glass reflecting the full glow of the moon.

“How do I get in there?” Betty said too loudly.

“Sssssh,” I cautioned. “Over here, duck under these vines.”

Betty crawled under the thick growth and sat back on her haunches.

“Hey, this is too much. How’d you find it?”

“I dunno. I just stumbled onto it.” And then I told her about the cats and Bessie O’Leary touching me on the shoulder and how I bolted out of there and practically dove into the hideaway.

She sat in silent awe. “Weren’t you scared? Even for a minute?”

“Naw. Well, sure, let’s face it. It’s not something I would want to do again. But I did it,” I added quickly. “And nobody else ever did.”

“Yeah, boy, Sully, I never knew you were so brave.”

“If you want the truth, Betty, I never knew it either. Something inside kept telling me to go into that cellar.”

“Gee. Gee,” she kept saying. Betty Martin was pretty, with shiny black hair and the whitest teeth in the Park. She went to St. Bart’s, and her oldest brother was in the Air Corps—in supplies. I never thought that sounded very brave. I knew that if I ever had to go—if the war lasted until I grew up—I would join the infantry so I could wade through the water and attack enemy beaches, maybe even use a flame thrower.

Right now as she sat beside me in the dark, I could almost see those white teeth flashing. She was wearing shorts and a peasant blouse, the same kind Jean Peters wore in Captain from Castille.

Neither of us said anything so I broke the silence by offering a plan for getting back to the Green Box. “When they don’t find us in the Park, they’ll come looking for us and as soon as they do, we’ll cut through Jugger’s yard, climb the fence and sit there waiting for them.”

“Gee, I don’t think we should cut through Jugger’s. It’s too dangerous. He might be out.”

I explained how I saw Jugger go into the house for the night. But I didn’t tell her anything else, like the uniform and stuff.

“You mean, you were right there behind a tree and he never saw you?”

“Yeah.”

“But weren’t you scared? Well, I guess not if you could go into Bessie O’Leary’s cellar. Gee, Sully, you really surprise me.”

“Why? What’ya think I was, a pansy or something?”

“Well, no, but you’re different than the other kids.”

“How?” I was on the defensive.

“Well, you never get into trouble, and you read books, and you tell funny stories—and you always go home when you’re ’sposed to. And Miss Feeney always trusted you with the key to The Green Box. She never let anybody else open it.”

“Yeah. I ’spose you’re right. But, you don’t think I’m a pansy, do ya?”

“Of course not. Especially after tonight. Gee.”

Suddenly I touched her arm. “Ssssssh, I heard something. Did you?”

“No,” she whispered.

“There it is again.” The sound of footsteps and muffled voices came from the direction of Joe Cushing’s store.

“They’re coming up the path. Here, get back into the bushes more.”

She lifted herself by the palms of her hands and we both moved deeper into the brush.

“Where the hell do you suppose they are? We’ve looked everywhere.” It was Birdie’s voice again and he and his Searchers were stopping right in front of our secluded den.

“Him and Betty are the last ones out. Maybe they’re makin’ out someplace.”

Stretch, who always had one thing and one thing alone on his mind, had now joined forces with Birdie. That’s how it always was. At the end of the game those who were caught always chickened out or sold out, like Peter Lorre, and came looking for those who were still out.

I could have bashed Stretch’s head with a rock when he said that about “makin’ out.” I wondered what Betty thought but I didn’t dare look at her for fear I’d make a noise.

“Naw, not Sully. He’s probably got his altar boy suit on and sayin’ the Rosary.” Birdie laughed at his own jokes all the time and most always everybody joined him as they did now.

A hand rubbed against my arm, a smooth, soft hand, moving up and down my arms. Betty was telling me to pay no attention to them, and I thought that was very nice of her but I still didn’t move.

“You think Sully went home?” Poirier probably hoped that I did, so he could razz me the next day at the Park.

“No,” Stretch said. “Sully always plays by the rules. He’d tell us. I know he would.”

“Yeah, that’s what you think,” crossed my mind, because until Betty joined me that’s exactly what I was going to do. “Come on, let’s check the Ledge. I’ll bet he’s holed up behind the rocks.”

They prowled on in the direction of the Ledge at the top of the hill. It was rocky on one side, the side we used to do our sledding, while the rest of it was open with tall grass. I had used it before and once I was caught there.

When their voices trailed off, I sat in awkward silence for a few minutes and then I said, “Well. Shall we make a run for it through Jugger’s?”

“Do you want to kiss me?” she asked.

At first I didn’t know what she meant, or what she had said. None of it registered, because she said it like, “Do you want a Coke, or do you want an ice cream, or do you want to go on the swings?”

“Yes,” I said without hesitation. It was like somebody else was speaking for me. It was a strange voice—the “Y” was deep and the “es” sort of cracked. My heart thundered in my ears. I leaned toward her and kissed her on the mouth. Her lips tasted like peppermint. She kissed me back. I was leaning almost off balance and supporting myself by my hands that clawed at the leaves. Then my arms went out and I felt her soft and warm against me as I pressed her down to the soft, piney earth.

My heart thundered against her right breast as I pulled her outstretched body into me. I was amazed at my actions as though I had made out with dozens of girls before. I stroked her hair and professed eternal love for her. Her blouse rode up from her shorts and my hand briefly fell on her bare stomach. I knew we had better stop, but she knew better than I.

“Boy, Sully, I think we had better find the Green Box.”

“Yeah,” I said with a husky voice, my hands trembling and my heart lodged somewhere in my head, tolling like some bell gone wild. “Yeah, let’s go back through Jugger’s.”

“Whatever you say, Bill.” My name, my regular first name sounded old and wise when she said it, like I had all the answers in the universe.

“I guess this means we’re going together, doesn’t it, Bill?”

“I guess so, Betty.”

“Can I write to my brother in the Air Corps and tell him?”

“Sure, why not,” I said, and added with my most recently acquired wisdom, “After all, he deserves to know what’s happening on the home front.”