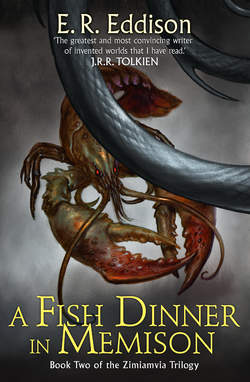

Читать книгу A Fish Dinner in Memison - E. Eddison R., James Francis Stephens - Страница 7

INTRODUCTION BY JAMES STEPHENS

ОглавлениеTHIS is a terrific book.

It is not much use asking, whether a given writer is great or not. The future will decide as to that, and will take only proper account of our considerations on the matter. But we may enquire as to whether the given writer does or does not differ from other writers: from, that is, those that went before, and, in especial, from those who are his and our contemporaries.

In some sense Mr Eddison can be thought of as the most difficult writer of our day, for behind and beyond all that which we cannot avoid or refuse – the switching as from a past to something that may be a future – he is writing with a mind fixed upon ideas which we may call ancient but which are, in effect, eternal: aristocracy, courage, and a ‘hell of a cheek’. It must seem lunatic to say of any man that always, as a guide of his inspiration, is an idea of the Infinite. Even so, when the proper question is asked, wherein does Mr Eddison differ from his fellows? that is one answer which may be advanced. Here he does differ, and that so greatly that he may seem as a pretty lonely writer.

There is a something, exceedingly rare in English fiction, although everywhere to be found in English poetry – this may be called the aristocratic attitude and accent. The aristocrat can be as brutal as ever gangster was, but, and in whatever brutality, he preserves a bearing, a grace, a charm, which our fiction in general does not care, or dare, to attempt.

Good breeding and devastating brutality have never been strangers to each other. You may get in the pages of, say, The Mahabharata – the most aristocratic work of all literature – more sheer brutality than all our gangster fictionists put together could dream of. So, in these pages, there are villanies and violences and slaughterings that are, to one reader, simply devilish. But they are devilish with an accent – as Milton’s devil is; for it is instantly observable in him, the most English personage of our record and the finest of our ‘gentlemen’, that he was educated at Cambridge. So the colossal gentlemen of Mr Eddison have, perhaps, the Oxford accent. They are certainly not accented as of Balham or Hoboken.

All Mr Eddison’s personages are of a ‘breeding’ which, be it hellish or heavenish, never lets its fathers down, and never lets its underlings up. So, again, he is a different writer, and difficult.

There is yet a distinction, as between him and the rest of us. He is, although strictly within the terms of his art, a philosopher. The ten or so pages of his letter (to that good poet, George Rostrevor Hamilton) which introduces this book form a rapid conspectus of philosophy. (They should be read after the book is read, whereupon the book should be read again.)

It is, however, another aspect of being that now claims the main of his attention, and is the true and strange subject of this book, as it is the subject of his earlier novels, Mistress of Mistresses and The Worm Ouroboros, to which this book is organically related. (The reader who likes this book should read those others.)

This subject, seen in one aspect, we call Time, in another we call it Eternity. In both of these there is a somewhat which is timeless and tireless and infinite – that something is you and me and E. R. Eddison. It delights in, and knows nothing of, and cares less about, its own seeming evolution in time, or its own actions and reactions, howsoever or wheresoever, in eternity. It just (whatever and wherever it is) wills to be, and to be powerful and beautiful and violent and in love. It enjoys birth and death, as they seem to come with insatiable appetite and with unconquerable lust for more.

The personages of this book are living at the one moment in several dimensions of time, and they will continue to do so for ever. They are in love and in hate simultaneously in these several dimensions, and will continue to be so for ever – or perhaps until they remember, as Brahma did, that they had done this thing before.

This shift of time is very oddly, very simply, handled by Mr Eddison. A lady, the astounding Fiorinda, leaves a gentleman, the even more (if possible) astounding Lessingham, after a cocktail in some Florence or Mentone. She walks down a garden path until she is precisely out of his sight: then she takes a step to the left, right out of this dimension and completely into that other which is her own – although one doubts that fifty dimensions could quite contain this lady. Whereupon that which is curious and curiously satisfying, Mr Eddison’s prose takes the same step to the left and is no more the easy English of the moment before, but is a tremendous sixteenth- or fifteenth-century English which no writer but he can handle.

His return from there and then to here and now is just as simple and as exquisitely perfect in time-phrasing as could be wished for. There is no jolt for the reader as he moves or removes from dimension to dimension, or from our present excellent speech to our memorable great prose. Mr Eddison differs from all in his ability to suit his prose to his occasion and to please the reader in his anywhere.

This writer describes men who are beautiful and powerful and violent – even his varlets are tremendous. Here, in so far as they can be conjured into modern speech, are the heroes. Their valour and lust is endless as is that of tigers: and, like these, they take life or death with a purr or a snarl, just as it is appropriate and just as they are inclined to. But it is to his ladies that the affection of Mr Eddison’s great and strange talent is given.

Women in many modern novels are not really females, accompanied or pursued by appropriate belligerent males – they are mainly excellent aunts, escorted by trustworthy uncles, and, when they marry, they don’t reproduce sons and daughters, they produce nephews and nieces.

Every woman Mr Eddison writes of is a Queen. Even the maids of these, at their servicings, are Princesses. Mr Eddison is the only modern man who likes women. The idea woman in these pages is most quaint, most lovely, most disturbing. She is delicious and aloof: delighted with all, partial to everything (ça m’amuse, she says). She is greedy and treacherous and imperturbable: the mistress of man and the empress of life: wearing merely as a dress the mouse, the lynx, the wren or the hero: she is the goddess as she pleases, or the god; and is much less afraid of the god than a miserable woman of our dreadful bungalows is afraid of a mouse. And she is all else that is high or low or even obscene, just as the fancy takes her: she falls never (in anything, nor anywhere) below the greatness that is all creator, all creation, and all delight in her own abundant variety. Je m’amuse, she says, and that seems to her, and to her lover, to be right and all right.

The vitality of the recording of all this is astonishing: and in this part of his work Mr Eddison is again doing something which no other writer has the daring or the talent for.

He is also trying to do the oddest something for our time – he is trying to write prose. ’Tis a neglected, almost a lost, art, but he is not only trying, he is actually doing it. His pages are living and vivid and noble, and are these in a sense that belongs to no other writer I know of.

His Fish Dinner is a banquet such as, long ago, Plato sat at. As to how Mr Eddison’s philosophy stands let the philosophers decide: but as to his novel, his story-telling, his heroical magnificence of prose, and his sense of the splendid, the voluptuous, the illimitable, the reader may judge of these things by himself and be at peace or at war with Mr Eddison as he pleases.

This is the largest, the most abundant, the most magnificent book of our time. Heaven send us another dozen such from Mr Eddison,

JAMES STEPHENS

15th December 1940