Читать книгу The Nature of College - James J. Farrell - Страница 29

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

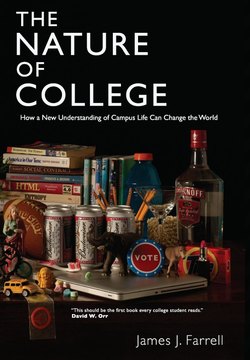

The Social Construction of Necessity

ОглавлениеMost student rooms and apartments conform to the expectations of what we might call “the standard package.” Though this “package” corresponds more or less to college recommendations about what to bring, it conforms even more to the expectations of college culture, a culture increasingly shaped by the marketing and ministrations of commercial culture.

In the American system of supply and demand, advertisers are the people responsible for supplying the demand, and they’ve recently discovered that “Back to College” is a lucrative market in several ways.4 Marketers realize that college students socialize each other in the art of consumption, so it’s important for them to teach students how to teach each other. Starting around the year 2000, therefore, retailers created “Back to College” as a fully merchandised market niche, offering American consumers another occasion for giving and getting. Retailers as diverse as Target, Wal-Mart, IKEA, The Container Store, Linens ’N Things, and Bed Bath & Beyond began to educate students with catalogs, websites, e-mails, “College Nights,” and gift registries, as well as flyers advertising freebies and student discounts. This “consumer education” has been an overwhelming success: By 2006, the National Retail Federation estimated that back-to-college spending would reach thirty-six billion dollars, making it the most lucrative shopping season in America after the winter holidays.5

In 2007, Amazon.com offered a website for students heading to campus, calling college “the final frontier (of your education, anyhow).” They offered interactive photos of “three student habitats: the Sweet Suite, the Dude’s Den, or the Study Space.” The pink-and-flowery Sweet Suite was for coeds. The Dude’s Den was a guy’s room. And the Study Space was gender neutral. As an online shopper dragged her mouse over the pictures, pop-ups explained the accessories and necessities of college life. Laptop computers appeared in all three rooms. “You can’t do college without a computer,” a pop-up asserted. “How can you stretch a 2-page paper to three pages if you can’t make incremental changes to the margins and font size?” Refrigerators also seemed to be part of the standard package: “Primitive peoples preserved food for later consumption by drying, curing, and salting. Good information to retain for your anthropology midterm, but we recommend a more modern method called ‘a fridge.’ ” Amazon advised girls that it’s a “new season, new school, new look, new you,” and invited them to “outfit yourself in the latest, the cutest, and/or the comfiest.” It reminded guys that they need video games: “Grab a couple rounds of Big Brain Academy on your DS Lite between classes, or slaughter your buddies in Halo 3. Ah, catharsis.” For every consumer category, Amazon offered a variety of choices and a lot of things to buy.6

The whole idea is to create a space where the student feels at home—and that involves creature comforts. In America, home is where the heart is. But Americans make a house a home by filling it with things that express our lifestyle and values, and students make their new spaces homey in the same way. In the past, students made do with what the college provided, but most modern students don’t. Instead, Jo and Joe College make over what the college provides by bringing in carpets, futons, beanbag chairs, lamps, electronics, curtains, comforters, and other lifestyle accessories, each creating “my space” in one of the identical rooms in a dorm corridor. In this consumer individualism, our choices reflect who we are (or who we’d like to be), but they also reflect our desire to fit in. The marketing consultants at Teenage Research Unlimited call the process “indi-filiation,” a magical mix of individualism and affiliation that lets us express our uniqueness—just like everybody else.7

Although it’s ultimately individual, off-to-college spending begins as a family affair: Advertisers tell parents that a spending splurge is the best way to express their love and mark this important rite of passage. “This is one of the largest emotional transitions people ever make,” says consumer psychologist Kit Yarrow, “and shopping is a way to reduce anxiety. People feel in control when they’re shopping. It’s something we do really well as Americans.” As a result, parents who are about to become empty nesters try hard to fill up the new nests of their offspring.8

There’s much more to this marketing effort than a single season’s sales. As Tracy Mullin of the National Retail Federation explains: “Retailers are hoping to not only boost this year’s sales but also to gain customers for life.” Marketers know that college students are in a position to establish lifelong brand loyalties for a new set of products. Even though current students already wield billions of dollars of discretionary spending annually in the United States, graduates will spend a lot more in the future. Student consumers are also early adopters of new technologies and artifacts—so marketers know that the latest items in today’s dorm rooms will be the standard stuff in tomorrow’s homes, apartments, and condos. In this way, college students foreshadow the materialism of the future.9

Whether or not students purchase anything at Best Buy, IKEA, Amazon, or Wal-Mart, the efforts of marketing departments shape the expectations of college consumers. Before they even get to classes, everyone learns that college is not a place apart, a reflective retreat from the everyday world—it’s just another market niche with its own consumer choices. Advertisements teach “ensemble thinking,” the idea that all of our things together should express a clear message about taste and values, as well as the art of comparison shopping—not comparing items to get a good price, but comparing our consumption to those immediately around us. Instead of going to college to “find themselves,” students seem to be going to school to express themselves with stuff.10,11

For the past several years, I’ve asked students in my Campus Ecology class to audit their rooms, compiling lists of all their belongings. One such list, reproduced verbatim, includes:

The quantity of commodities in the average college dorm room today is radically different from one hundred years ago. In those days a student might have three or four changes of clothes, and two or three pairs of shoes. Students took the train to college instead of arriving in cars, trucks, and vans pulling U-Haul trailers. The amount of stuff was limited, more or less, by what you could carry—or what you could fit into a steamer trunk. Furnishings were Spartan, both by necessity but also by choice: College was a place where—freed from the clutter of the material world—a student might think clearly about the purposes of life. And surprisingly enough, many of them survived their studies without lofted beds, designer lighting, or shag carpets.

All the stuff in dorm rooms today is a testament to the social construction of necessity. In a prescient 1962 essay titled “A Sad Heart at the Supermarket,” poet Randall Jarrell identified the shifting nature of necessity:

As we look at the television set, listen to the radio, read the magazines, the frontier of necessity is always being pushed forward. The Medium shows us what our new needs are—how often, without it, we should not have known!—and it shows us how they can be satisfied: they can be satisfied by buying something. The act of buying something is at the root of our world; if anyone wishes to paint the genesis of things in our society, he will paint a picture of God holding out to Adam a check-book or credit card.

Because marketers and manufacturers need us to need, they work hard to create new necessities both in college and American life, “upscaling” yesterday’s luxuries into today’s necessities. And so the “buyosphere” expands over time, but the biosphere, by nature, does not—and that’s a problem.12