Читать книгу The Nature of College - James J. Farrell - Страница 34

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

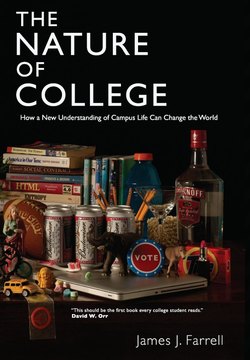

The Really Good Life

ОглавлениеWhen we furnish our rooms or fill our closets, we say “I want that,” but we also tell manufacturers “make more of that”—setting in motion a whole process of extraction, production, distribution, marketing, and sales. In the process, we tell each other that this level of consumption is normal, natural, and good. We buy into a system of commercial capitalism, a story of nature converted to commodity, converted eventually to garbage. Each of our decisions, therefore, is a case study in ethics, a determination about the nature of “the good life.” As we peruse the stuff available to us, we’re making judgments about which goods are good for us and why. We don’t think we’re engaged in ethical reflection, but we are deciding what we value, and how we will embody our values in the material world. Our rooms and our belongings send messages about identity and community, but they also express our ethical sensibilities, whether we like it or not.24

The problem, it seems, is that we apply ethical norms almost exclusively in our face-to-face and intentional interactions. We don’t feel responsible for what we don’t see and don’t intend. In a system of invisible complexity, we don’t usually consider our inevitable complicity in this system of material goods. Consequently, we seldom think of our everyday purchases in terms of value—except, of course, when they’re cheap enough to be a “good value.” But style itself is a value, and the ability to keep ethics out of aesthetic judgments is also a value. The question for consumers—which is all of us—is how we can take responsibility for the systems that provide our belongings. When Chinese workers are poisoned in the process of recycling our computers, what is the moral implication for us? The answer might be as simple as paying attention to our things, but saying that it’s simple doesn’t make it easy.