Читать книгу Last in Their Class - James Robbins - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

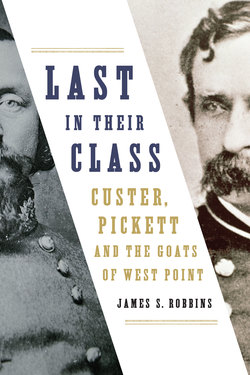

ОглавлениеHENRY HETH

DABNEY MAURY, A VIRGINIAN who graduated near the middle of the Class of 1846 and who later served as a Confederate major general, said that the four years he spent at West Point were “the only unhappy years of a very happy life.”1 Maury’s friend Henry Heth, fellow Virginian and Goat of the Class of 1847, had a much different experience. “Dabney was a good boy at West Point,” Heth observed, “but he was not happy; I was not good, I was happy, and had a good time.”2 It was clear from the very beginning that Heth would enjoy his stay at West Point—he chalked up his first two of many demerits for “Laughing in ranks at morning parade.”3

Henry Heth was born in 1825, the fourth of eleven children of John and Margaret Pickett Heth of Blackheath, Chesterfield County, Virginia. John had served in the Navy under Decatur in the War of 1812, and later was a successful plantation owner who, as head of the Heth Manufacturing Company, also ran lucrative coal and iron concerns. Henry had been well prepared for the academic rigors of West Point. He had matriculated at Georgetown College, which was then a prep school, at the age of twelve, moved on to the Muhlenburg School on Long Island, and finally attended the Peugnet Freres School for Boys in New York. The Peugnet brothers were former French officers who had fought under Napoleon, and they thrilled their charges with tales of the great European battles of the past. The Peugnets specialized in preparing candidates for the Military Academy, and in his two years there Henry grew proficient in French and mathematics, still mainstays of the West Point curriculum.4 Henry’s father died while he was at Peugnet’s, and family friend President John Tyler, in sympathy, offered Henry a commission as a midshipman. Margaret Heth turned down her son’s appointment, and Tyler countered with a presidential appointment to West Point, which Henry accepted.

Heth sailed north to West Point in 1843. Like Nathaniel Wyche Hunter and most other cadets, he arrived during the summer encampment. Unlike Wyche, he was protected from most of the indignities inflicted on new cadets by his cousin George Pickett, who was then a yearling and described by William M. Gardner, Class of 1846 and later a Confederate brigadier general, as “a jolly good fellow with fine natural gifts sadly neglected. He was a devoted and constant patron of Benny Haven, [a man] of ability, but belonging to a cadet set that appeared to have no ambition for class standing and wanted to do only enough study to secure their graduation.”5 The two cousins became boon companions, the core of a cadet clique that did not have the patience to wait until after graduation to seek adventures.

George Pickett would make his mark as one of history’s most famous Virginians, but he was appointed to West Point from Illinois. After his death, the general’s widow, LaSalle “Sallie” Pickett, wove an intriguing story around Pickett’s appointment, which over the years grew in the telling. The tale goes that in the early 1840s, when young George was studying law in Illinois, he occasioned to meet Congressman Abraham Lincoln. Pickett, who did not know Lincoln’s identity, spoke to him of his secret ambition to become a soldier. Lincoln took note of the young man’s aspiration, and soon afterwards, to his surprise, Pickett was notified that he had been appointed a cadet at West Point. This inspired a lifelong loyalty, and during the Civil War, Pickett would rise to the defense of Lincoln if anyone said anything negative about the president in his presence. One of Sallie’s stories has it that when Lincoln visited Richmond after its fall in April 1865, he stopped by the Pickett home and was met by Mrs. Pickett, holding her infant son, George Pickett Jr.

“Is this George Pickett’s house?” Lincoln asked.

“Yes, but he’s not at home.”

“I know that Ma’am, but I just wanted to see the place. I am Abraham Lincoln.”

“The President!” she gasped.

“No Ma’am! No Ma’am, just Abraham Lincoln, George’s old friend.”

“I am George Pickett’s wife,” she said, “and this is his baby.” George Jr. reached out to Lincoln, who took the baby in his arms and kissed him.

“Tell your father, the rascal, that I forgive him for the sake of that kiss and those bright eyes.” He then handed little George back to his mother and left.6 The tale of Lincoln’s visit is a compelling story of irony and forgiveness, and would be extraordinary if true. Sadly, no other witnesses attest to the story, and it was probably the product of Mrs. Pickett’s hagiographic impulses. An 1842 letter from Lincoln to Pickett on his appointment, full of fatherly advice and homespun wisdom, discovered in the early twentieth century, turned out to be a forgery. Furthermore, Lincoln served only one term in Congress, 1847–49, by which time Pickett had already graduated.

But while the particulars of the myth are easily disproved, there is at least a tincture of truth in it. Pickett did go to Quincy, Illinois, in the early 1840s to study law with his uncle Andrew Johnston. Pickett was appointed to West Point through the office of Johnston’s friend John Todd Stuart, a congressman from Illinois. Stuart had previously served as a volunteer major in the Blackhawk War, where he had met Lincoln, then captain of a volunteer company. (Both had been mustered into service by Regular Army Lieutenant Jefferson Davis.)7 Stuart and Lincoln served in the state legislature together and became law partners. Lincoln later married Stuart’s cousin, Mary Todd. Andrew Johnston and Lincoln were also close friends, and Johnston was responsible for the only known publication of a Lincoln poem, when he had some verse Lincoln had written him in a letter published in the Quincy Whig, May 5, 1847.8 Thus while the tale of the Lincoln-Pickett connection has been exaggerated, it is not a complete fantasy. It would be more difficult to believe that Johnston never bothered to introduce his nephew the prospective lawyer to his two successful friends in the west Illinois legal fraternity. Ironically, the only cadet that Lincoln nominated while in Congress was Hezekiah H. Garber of the Class of 1852, who like Pickett graduated as the Goat.9

The West Point that Pickett and Heth attended was subtly different from the institution Thayer had created. Major Rene DeRussy of the Class of 1812 followed Thayer as Superintendent and retained all the academic aspects of the Thayer system, which established it beyond question.10 DeRussy, however, was not the disciplinarian that Thayer had been, and he relaxed some of the stricter standards on cadet behavior. He allowed alcohol to be served again at the Fourth of July dinners, and unlike Thayer, who kept his distance from these festivities, DeRussy joined in. His easygoing approach was popular with cadets, and punishments grew so lax that even Thayer’s bête noire President Jackson mandated that West Point be “more rigorous in enforcing its discipline.”11

DeRussy served five years as Superintendent and was succeeded in 1838 by Major Richard Delafield, known as “Old Dickey.” Delafield had graduated first in the Class of 1818, the first class of the Thayer era. He thus may have felt a special responsibility to preserve the Thayer legacy. Like DeRussy, he maintained the continuity of the system, but he was much stricter than his predecessor, and so was not liked by cadets. They showed their disregard for him in various harmless ways; for example, two of Delafield’s pet ducks were caught and eaten, and cadets would occasionally corral his cow, which was accustomed to grazing on the Plain, to exploit the supply of fresh milk. In 1843 when Delafield banned the traditional cadet practice of having Christmas Eve suppers in their rooms, the Corps boycotted the elaborate catered feast and dance he had arranged in the drill hall. A cadet officer looked in on the desolate scene, and later noted in a letter home, “I really pitied the old gent, after all the pains he had taken—however it will learn him that he can’t control a body of men in their amusements or at any rate that he can’t make a man enjoy himself if he don’t wish to.”12

Delafield was assisted in his tasks by Commandant John Addison Thomas, Class of 1833, a strict disciplinarian who also was not loved by the cadets. He had been at USMA almost his entire career, as a Tac and professor before becoming Commandant. Since he had formerly taught ethics, his cadet nickname was “Ethical Tom,” though he insisted on signing his name “J. Addison Thomas.” He was vainglorious and affected a martial bearing, which was not out of place at the Academy but was noteworthy because it was so obviously artificial. He was fond of his full-dress uniform as an officer of artillery, with its towering hat and red plume. A cadet described him during parade: “This resplendent being appeared before us as a radiant vision, and with clanking saber and whiskers of most precise military cut, strode like a field marshal along our ranks, transfixing each of us in turn with the fierceness of his eagle eye.”13 Thomas too was the object of occasional expressions of discontent, such as the time his office was flooded by some cadets he had given Saturday punishment. Thomas’s wealthy wife eventually convinced him to leave the Army and become a lawyer, and when his departure was announced to the Corps in late October 1845, after ranks were broken the cadets raised their hats and spontaneously gave three cheers, three times. “This was insubordinate conduct,” Cadet George H. Derby explained, “but it could not be punished for there were no ringleaders, and all they could have done would have been to dismiss the whole corps.”14 Later that evening the cadets celebrated with an illumination of the barracks and a serenade of drums, and those who were caught were punished.

In addition to the efforts of DeRussy and Delafield, the Thayer system persisted because of the continuity in curriculum and faculty, particularly in the person of Dennis Hart Mahan. Boy genius of the Class of 1824, Mahan was chosen by Thayer as his intellectual successor. He spent four years in Europe studying modern methods of war, and attended the French Military School of Engineers and Artillerists at Metz. In 1832, at age twenty-nine, he became the head professor of engineering at the Academy, a post he retained for almost forty years. He was the author of numerous books, and his textbook on tactics was highly influential and reprinted without permission by the Confederate government during the Civil War. Mahan was also a deft and able public defender of the Military Academy against its critics. He paid special tribute to the father of the Academy in 1840 when he named his newborn son Alfred Thayer Mahan.15

Dennis Mahan was brilliant, cold and sarcastic, not a favorite among the cadets, who respected and feared him. He brooked no disagreement from his students (or anyone else, for that matter), but those whom he taught learned their subjects well. Due to a slight speech impediment, Mahan spoke as though he had a head cold, and “as he was constantly telling his pupils to use a little cobben sense he at length got to be known—such is the irreverence of cadets—as ‘Old Cobben Sense.’”16 One piece of advice he doled out concerned marriage. Mahan’s wife, Mary Helena, was a beauty whom he had met at a cadet hop in 1830. Their courtship lasted nine years, and Mahan later told cadets that nothing was more foolish than for a young officer to get married, and a wife was a luxury that should not be thought of until one reached the rank of captain.17 The question of whether it would be beneficial to forbid officers under the rank of captain from marrying was debated by the Dialectic Society in September 1840, and the resolution was defeated 11 to 4. Cadets were forbidden to marry while at the Academy, but many found themselves in wedlock soon after graduation despite Mahan’s sagacious advice.

Completing the course of studies and graduating from West Point did not get any easier in the post-Thayer years. In Pickett’s class, 133 young men were appointed, of whom 122 actually made it to the Academy. At the first January examination, 30 were found deficient and had to “take the Canterbury Road,” i.e., go back home; 56 of the remaining 92 would go on to graduate, but only 47 of them graduated in four years; the other 9 completed in 1847. So Pickett, even as the Goat, was like the other Immortals a survivor.

During the period before the Mexican War, the Corps saw pass through its ranks cadets who would later win fame on the battlefields of the Civil War. The class rosters of those days read like a Who’s Who of the War Between the States. Yet none at the time knew the struggles they were preparing for, or which among them were marked for greatness. Class rank was not a good predictor. During his commencement speech for the Class of 1886, Brigadier General John Gibbon, Class of 1847, noted, “one cannot help being struck with the remarkable, sometimes whimsical, way in which the dice-box of Fate has apparently belied all prognostications formed here. . . . Who cannot recall instances of boys whose future the most exalted estimates were made, and who, when the great test of life was applied, were never heard of? Who has not been amazed at the way in which some, never associated in our minds with greatness, have shot up into well-merited prominence?”18 He envisioned a roll call of his cadet company by a sorcerer with the gift of prescience, telling each man his fate. Gibbon, who graduated 20th in a Class of 38, began the Civil War as a captain and ended it as a brevet major general, being wounded several times and promoted for bravery at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, Spottsylvania and Petersburg. He was born in Pennsylvania but grew up in North Carolina and was appointed to West Point from there. His three brothers fought for the Confederacy and his family disowned him as a traitor. His entry to West Point was delayed a year because on his entrance exam he did not know the correct date for Independence Day. Of the Class of 1847 as a whole, sixteen would rise to general officer rank, but none of the generals came from the top five “star men” of the class. Four of the class would die in combat, including one of the generals, Ambrose Powell “A. P.” Hill, who was killed at Petersburg in the last week before Appomattox.

Professor Mahan, unlike Gibbon, was a believer in the infallibility of the Thayer system. The continual process of testing and ranking the cadets—not just twice yearly but weekly—was to him an objective winnowing, and its product as accurate an indicator of future potential as could be devised. This, of course, was easy for a star man to believe. John C. Tidball of the Class of 1848, who rose to the rank of brevet major general in the Civil War and who was briefly Commandant of Cadets in 1864, wrote later that Mahan “regarded Grant, Sheridan and others who did not have high class standing as mere freaks of chance.” The high-ranking graduates who held important leadership posts in the opening years of the war affirmed the judgment of the Academic Board; “but when success did not perch upon their banners hope fled, and when, finally, those of inferior standing rose to distinguished leadership the world was turned topsy-turvy. Then the days were indeed gloomy for the professor.”19

One of the most noteworthy “freaks of chance” was indeed Ulysses H. (later S.) Grant, of the Class of 1843, whom Dabney Maury described as “a very good and kindly fellow whom everybody liked.”20 He is often thought to have been a Goat, but he was not, having graduated firmly in the middle of his class, 21st of 39. The idea that Grant performed poorly in school probably stems from a temptation to make him the anti-Lee. In many ways he was—Blue vs. Gray, westerner vs. easterner, son of the middle class vs. scion of the aristocracy, plainspoken vs. eloquent, rough-hewn vs. well groomed—it is too tempting to add to the list “Goat vs. Star.”21 But while not a Goat, Grant was hardly an ideal student. Looking back on his cadet years, he recalled that “military life had no charms for me, and I had not the faintest idea of staying in the Army even if I should be graduated, which I did not expect. . . . I did not take hold of my studies with avidity, in fact I rarely read over a lesson the second time during my entire cadetship.” Grant said he spent most of his study time devouring novels, though “not those of a trashy sort.”22 When Congress debated a bill in December 1839 to close West Point, Grant favored the measure as “an honorable way to obtain a discharge.”23 Grant’s lowest marks were in ethics and French, in which he was very poor, and in his final year his worst showing was in infantry tactics. But his other grades were decent and his disciplinary record was not extraordinarily bad; he did not get involved with hazing and he blew post to Benny’s only once.

Grant’s friend James Longstreet explained, “as I was of large and robust physique I was accomplished at most larks and games. But in these young Grant never joined because of his delicate frame.”24 Yet Grant was without equal in one area of study, horsemanship. He was a daring rider who took risks that others would not. The riding hall was a large space in the Academic building, which was not well adapted to the purpose, particularly because of the numerous iron support pillars around which cadets had to maneuver. They would guide their mounts about the hall, chopping at posts with straw-filled heads on top, poking their sabers through rings hanging above them, and leaping over wooden poles held by enlisted dragoons. Grant favored a foul-tempered sorrel called York that other cadets feared, and he would leap the animal over bars six feet high or higher. A hash was placed on the wall to mark Grant’s highest leap, which was never beaten. Longstreet said that when Grant was in the saddle, “Rider and horse held together like the fabled centaur.”25 Once while Grant was riding a particularly spirited mount, the saddle girth broke, sending the rider tumbling. “Cadet Grant,” the riding master said, “six demerits for dismounting without leave.”26

Henry Heth was also credited as the best rider in his class, and was once given demerits for improvising a spur by placing a nail in his boot. Heth, like Grant, had no desire to compete for class ranking. “My four years career at West Point as a student was abominable,” he wrote. “My thoughts ran in the channel of fun. How to get to Benny Havens’ occupied more of my time than Legendre on Calculus. The time given to study was measured by the amount of time necessary to be given to prevent failure at the annual examinations.”27 Unlike Nathaniel Wyche Hunter, who constantly worried about being able to pass and feared the worst with every exam, Heth was fairly certain he could complete the curriculum, provided it did not interfere with his amusements, or vice versa. His previous schooling, especially at Peugnet’s, may have helped inculcate this attitude. He found himself overprepared, or so he thought. “For the first six months [at West Point] I scarcely ever opened a book,” he wrote. “I thought I knew it all, but often found, to my sorrow, that I was sadly mistaken when the X-rays of the professor were turned on my perfunctory knowledge of the subject.”28

At the other end of the scale, the cadets in the first section had a “glamour of sanctity shimmering about [them] which causes its members to be regarded as a sort of intellectual aristocracy.” This was Tidball’s impression; he had worked his way up from the Immortals and was nervous about joining those whom he had made his peers:

It was with palpitating forebodings I took my place among them; but I soon discovered I had little to fear on this score. I found, it is true, a very great difference between this section and those near the foot of the class, but I did not, on the other hand, find in it that transcendent brilliancy I had been led to believe existed there.29

Tidball discovered that those at the top were typically cadets who had excelled early in math and held on through hard study. He said there was an unwritten law that “none could be admitted to the first section in mechanics and engineering who had not been in the first section in mathematics. And this custom assisted in making the first section a close corporation, fostering the before-mentioned notion of intellectual aristocracy.”

Those who aspired to join the top ranks would have to apply themselves diligently, and not everyone thought it was worth the effort. But perspectives on rank were relative, and proximity could breed contempt. Cadet George Derby, who had always done well in his studies and been consistently in the top ten, thought those above him were insufferable grinds who had an unseemly obsession with plaudits. (Those below, of course, might have thought the same of him.) He finished his third year ranked fifth in his class, a distinguished cadet aiming for a commission in the Engineers. He felt that he could have been first in the class had he tried, but he chose instead to do only enough to maintain the standing he needed. Anyway, the top of the class was not all it was made out to be; in Derby’s opinion, the top men were insecure, egotistical and generally unlikable. “With moderate study I get calmly and comfortably along,” he wrote in the fall of his final year, while

the men above me are filled with envy, jealousy, and all sorts of bad passions, nothing is too small for one or two of them to do to get a better mark than those above them. They study nights, they draw on their problems at unauthorized hours, they neither think nor care for anything but their mark, and their continual bickerings, and jealousies, and boastings, and exultations are enough to make anyone sick of the sight of them. Now I dare say (and without much vanity either) that if I were to make such an ass of myself as all this I might stand above them all—but I should not gain much in self-respect, or in the opinion of any of my classmates or officers.30

Alas for Derby, he relaxed a bit too much in his final year and graduated seventh, missing both the designation of Distinguished Cadet and a commission in the Engineers. But he went on to become a hero in the Mexican War and to win more lasting celebrity as a humorist writing under the name John Phoenix.

One of those with whom Derby competed was the future Union army commander George B. McClellan, who had entered West Point at the age of sixteen and had also always ranked near the top. He was fourth in the class entering the final year, but as Derby dropped two slots, McClellan rose two, and he could have graduated first but for a disciplinary infraction. The top man, C. Seaforth Stewart, served honorably for forty years, but rose only to the rank of colonel.

The quest for rank and class standing became an unhealthy obsession for some. Plebe Benjamin Baden, for instance, passed away October 19, 1837, at the age of sixteen, because his classroom performance had been substandard. Cadet William Tecumseh Sherman, then seventeen, wrote to Ellen Ewing, then thirteen and a half (later his wife), that Baden was “proud and ambitious but unfortunately was not able to succeed in his studies which so mortified him that he was taken sick and five days afterwards was a corpse.”31

The West Point entrance exam in those years required only an understanding of the four fundamental rules of arithmetic, the ability to read, good handwriting skills and passable spelling. Decades later William Gardner observed that “if the present high standard had then obtained, many men since distinguished in our national history would certainly have been rejected.”32 Among them in particular was his classmate Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, who arrived at West Point an unprepossessing figure wearing gray homespun and a wagon-master’s hat, with a pair of worn saddlebags slung across his shoulders. Maury said that Jackson “was awkward and uncultured in manner and appearance, but their was an earnest purpose in his aspect which impressed all who saw him.”33

Jackson had secured his position at West Point when another appointee decided not to attend at the last minute, and Jackson took his slot.34 He failed his entrance examination, but was allowed to try again in September, and he passed. Jackson was something of a loner at West Point, a student who knew he had to study constantly if he wished to prevail. He spent most of his free time in his room, which he shared with George Stoneman, later a Union major general of cavalry and governor of California in the 1880s. Tidball said that “in consequence of a somewhat shambling, awkward gait, and the habit of carrying his head down in a thoughtful attitude, he seemed less of stature than he really was. . . . Being an intense student, his mind appeared to be constantly pre-occupied, and he seldom spoke to anyone unless spoken to, and then his face lighted up blushingly, as that of a bashful person when complimented. . . . When a jocular remark occurred in his hearing he smiled as though he understood and enjoyed it, but never ventured comment to promote further mirth.”35

With rare exceptions, Jackson did not socialize with the other cadets or visit them in their rooms. Despite his eccentricities, he was not the victim of much hazing, except once in class when he was asked to go to the boards, and upon standing revealed that someone had chalked across his back, “General Jackson” in large letters.36 Jackson’s studies paid off. A year after he failed the entrance exam, he ranked 51st of 83 in his class, his worst showing (70th) being in French. A year later he had jumped up to 30th of 78, though he was in the Immortal section in drawing. He rose another ten spaces by the end of his third year, though he had not improved his skill at drawing, ranking third to last. This was balanced by his 11th place showing in philosophy. Jackson continued to improve his standing up to graduation, finishing 17th overall in the Class of 1846 and 5th in ethics, with his worst grades, like Grant’s, coming in infantry tactics.

James Longstreet, an Immortal of the Class of 1842 who graduated third from the foot, and who would later serve with Jackson and A. P. Hill as one of Robert E. Lee’s corps commanders, was another of those who used his intellectual gifts chiefly to make free time available for other pursuits. Longstreet was born in South Carolina. His mother moved to Alabama after his father died in a cholera epidemic, and he was appointed from that state by a relative, Congressman Reuben Chapman. “As cadet I had more interest in the school of the soldier, horsemanship, sword exercise, and the outside game of foot-ball than in the academic courses,” he later recalled.37 Longstreet managed to stay just above the line of deficiency until the January examination in his third year, when he failed mechanics for not being able to demonstrate pulleys. He had never really paid much attention to the lesson. “When I came to the problem of the pulleys, it seemed to my mind that a soldier could not find use for such appliances,” he explained, “and the pulleys were passed by.” He was given a few days to study before being reexamined, at which point he was quizzed over the entire mechanics curriculum and allowed to continue. But in the June exam he was again faced with the problem of the pulleys. “The professor thought that I had forgotten my old friend the enemy,” Longstreet wrote, “but I smiled, for he had become dear to me—in waking hours and in dreams.”38 He passed that part of his exam with a perfect score, but it did not rescue his overall academic standing that year; and he ranked in the bottom ten of the entire Corps in conduct.

It was nearly impossible to escape demerits. “Few men have tried harder than myself to avoid demerit,” Cadet Derby wrote, “yet some little act of carelessness would fix them upon me, in fact when the cadet officers seek a man doing his best or as it is called ‘boning conduct’ they instead of assisting him rather take pains to report him when possible, probably with the benevolent object of making him still more careful.”39 The cadet officers would “skin” their fellows just to show higher authorities that they were being attentive to their duties, and officers brought elastic interpretations to the regulations that made obeying the rules a largely subjective enterprise. Edmund Kirby Smith of the Class of 1845 (brother of Ephraim, the Goat of 1826), nicknamed “Seminole” since he came from Florida, complained in a letter to his mother, “If I obeyed the regulations to the letter, I should make a perfect anchorite of myself. The Professors—Superintendent, etc.—twist-turn & change them to suit their fancies & should not we poor devils evade them to meet our necessities?”40 Edmund fared better than his older brother academically, graduating 25th of 41. He would go on to fame as commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederacy, who did not lay down his arms until over a month after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.41 He died in 1893, the last of the Confederate full generals.

Henry Heth’s disciplinary record was impressively long, filling three and a half folio pages. He was mostly skinned for the kind of infractions one might expect from someone seeking to perfect the role of the Goat as bon vivant: lateness, inattention, wearing slippers at reveille, visiting, being caught out of barracks (a serious infraction, worth eight demerits), distracting sentinels at post and making boisterous noise, talking in ranks, and looking around, swinging arms or spitting on parade. Pickett’s disciplinary history was of a similar sort, exhibiting the familiar social behavior, and was only a quarter page shorter than his cousin’s. But Pickett was more daring in allowing points to accumulate, and in his final year he came within five demerits of expulsion.

Cadet Lewis Addison Armistead, a future brigade commander in Pickett’s division and a relative of Heth’s, was less careful. Armistead came to West Point the product of a distinguished military family. He was named after two uncles who had died in the War of 1812. His Uncle George had commanded Fort McHenry during that war and defended the original “Star-Spangled Banner” against the British. His father, Walker K. Armistead, was the third graduate of the Military Academy and a brevet brigadier general in 1833 when he secured his son a presidential appointment. Despite years of prep school, Armistead was not academically gifted. Sickness prevented his taking the January 1834 exam and he was forced to resign. He was reappointed later that year and in January 1835 barely scored high enough to remain. At the end of the year he ranked 52nd of 57 cadets and was turned back. He raised his grade significantly by January of 1836, coming in 31st of 59 cadets, but he ranked close to the bottom of his class in discipline. His best-known infraction came when he cracked a plate over Cadet Jubal Early’s head in the mess hall in the winter of 1836. “Old Jube,” a future division commander under Lee, was also a member of the Class of 1837, along with such Civil War notables as Joseph Hooker, John Sedgwick, John Pemberton, Braxton Bragg and William H. T. Walker, the Immortal who survived four musket balls at the Battle of Okeechobee.42 On January 17, 1836, Armistead was placed under arrest for “disorderly conduct in the mess hall.”43 He was held for twelve days, after which he tendered his resignation from West Point rather than face trial and possible dismissal. But Armistead did not give up his dream of following in his father’s footsteps. He was commissioned a lieutenant in 1839 and served the next three years in Florida, one year as his father’s aide. In the Mexican War he won three brevets for bravery, and he served with distinction in the Army of Northern Virginia until falling mortally wounded at Gettysburg, leading his brigade in the Angle during Pickett’s Charge.44

Some cadets prevailed against all odds to get through West Point. Randolph Ridgely, for example, a hero of the Mexican War, was a rare case of a cadet who went through three plebe years. He was a classmate of Armistead’s, appointed from Maryland. Ridgely was first admitted in 1830 when he was just under sixteen years old, and had accumulated 198 demerits by 1831 when the 200 limit was instituted. The seven cadets below him were expelled. Though saved by a hair in discipline, Ridgely was found academically deficient. He was readmitted in 1832, grappled fitfully with his studies, and was turned back at the end of the academic year to start a third time. He worked doggedly for the next four years and finally graduated 42nd of 50 in the Class of 1837, seven years after he first came to West Point.