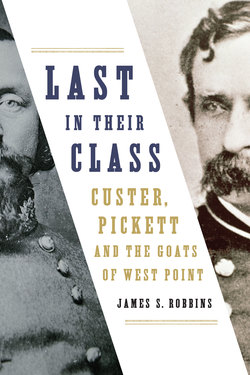

Читать книгу Last in Their Class - James Robbins - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE TO THE PAPERBACK EDITION

THE BEAR WAS A GOAT

GUY R. “BEAR” BARATTIERI graduated from the United States Military Academy at the very bottom of the Class of 1992, but he was emphatically not a failure. On the contrary, he displayed the dauntless spirit that has typified West Point’s “Last Men” since the days of George Custer and George Pickett. His story, like theirs, is a story of bold adventurousness, unflinching courage, and firm dedication to duty, honor and country. It shows that the spirit of the Goat wasn’t extinguished when West Point officials formally discontinued the tradition of celebrating the institution’s academic stragglers.

“Bear” got his nickname for his imposingly large build and strong, solid features. With his crooked smile, he was exceptionally friendly and loved by everyone. He was a football star in high school, playing outside linebacker on the undefeated Purcell Marian team in Cincinnati that won the state championship in 1986. He also played on Ohio’s all-state team. In 1988 he was offered a full scholarship to Penn State, but he turned it down. Bear had always dreamed of being a soldier, so he took his gridiron skills to the United States Military Academy instead.

Like so many West Point Goats before him, Bear was a fun-loving, charismatic, resourceful cadet who much preferred adventure-seeking to studying. One classmate, Dana Rucinski, said he was “one of the most cheerful, friendly, positive people at school. You couldn’t help but smile when talking to Bear, and nothing ever seemed to get him down—no matter what his academic worry of the week!”

Bear played on the West Point varsity football squad as a plebe, but injured his back and neck in his first season and was forbidden by Army doctors ever to play football again. It was a severe blow to him, since the sport had always been a big part of his life. But then, “demonstrating the lack of intellect and common sense” prevalent among Army rugby players, as classmate Chris Jenks put it, Bear “decided that technically the doctors never said he couldn’t play rugby.” So he joined the rugby team the next year and played “a devastating wing forward.”

What eventually kept Bear out of sports in his firstie (senior) year was his dismal grades, but he hung on and graduated on time, at the foot of his class. As is traditional, he received the loudest applause at the ceremony and was given a dollar by each of the other graduating members of his class. Some of his rugby pals had plans to help Bear spend his $961 windfall that summer during the Infantry Officers Basic Course, but by the time he showed up at Fort Benning the money was long gone.

Bear served first as an infantry officer, then became a Green Beret with the 1st Special Forces Group out of Fort Lewis, Washington. He deployed to the Balkans and served with distinction, winning the respect of all who came into contact with him. Bear left the Army as a captain in August 2000 to join the Seattle Police Department. He was much more serious about law enforcement training than he had been about his studies at West Point, and he finished at the top of his police academy class. He kept a hand in the military, too, serving as a major in the 1st Battalion, 19th Special Forces Group of the Washington State National Guard.

Bear’s unit was activated following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and in 2002 he found himself in Kuwait preparing for the invasion of Iraq. He fought bravely in Operation Iraqi Freedom. His team was attached to the 101st Airborne Division and led the way in the advance toward Baghdad in March 2003. Bear was credited with capturing three of the Iraqi leaders featured on the famous “Most Wanted” deck of cards, and was recognized with a Bronze Star citation.

He made several trips to Iraq, both with the Special Forces and working for private security firms. At one time he provided security for the Baghdad bureau of Fox News. “Bear arrived on his first assignment to head up our security team in Baghdad,” recalled the bureau chief, John Fiegener. “We all knew right away that Bear was the man. You just knew no one would mess with us because Bear would make sure of it.” When car bombs went off outside the bureau, Bear coordinated the response and kept the situation under control, staying calm through it all, according to Gordon Robison, a Fox producer. “When it was over he was confident and smiling, and that attitude helped the rest of us to understand that we, too, were going to make it through.”

Bear married his wife, Laurel, in Washington State in 2005, and in July the following year they welcomed a daughter into the world, naming her Odessa. But Bear was not yet through with the war. He returned to Iraq in late September 2006.

On October 4, 2006, he was part of a three-vehicle convoy supplying security near Forward Operating Base Falcon. He was riding in the back of the second vehicle, an armored Ford F -350 driven by Kurdish Peshmerga fighters. The group they were escorting was visiting a nearby power plant. On the way to the site, the streets had been lined with Iraqi police, but the egress route was empty. The security guard sitting next to Bear radioed, “Streets are clear. That’s kind of odd isn’t it?”

Three seconds later an IED ripped through their vehicle. The Kurds in the front were killed instantly, the driver’s body left burning and the passenger’s having disintegrated. The man next to Bear was severely wounded and slipped in and out of consciousness. Bear had lost both legs below the knee.

The other two vehicles in the convoy stopped to render assistance. Small-arms fire erupted immediately after the explosion, from both sides of the street and the nearby rooftops. All the attackers wore Iraqi police uniforms. The security detail returned fire while others helped the wounded men. Tourniquets were applied to Bear’s legs to keep him from bleeding to death. It took ten minutes working under fire to free the two passengers.

The two surviving trucks sped from the area and a running firefight ensued. The tail gunner of the trailing vehicle fired at anyone he saw wearing an Iraqi police uniform. The convoy drove to the International Zone, about thirteen kilometers distant, and went directly to the combat support hospital. Bear’s partner was declared DOA. Bear was taken immediately into surgery and stabilized, but he died a short time later in surgical ICU.

The news of Bear’s death was devastating to all who knew him. The National Guard Association of Washington established a “Bear Fund” for contributions to help support his young wife and their new baby and his stepdaughter, Rees. Scores of family, friends and coworkers attended his funeral.

Yet through the sorrow, the tributes to Guy Barattieri reflected his own joy of living. Those who knew him could not help but celebrate him for the spirit and liveliness he brought to everything he did. The Class of 1992 (motto: “The Brave and the Few”) honored him and other deceased members of the class at their twentieth-anniversary reunion at West Point. “Guy had an amazing capacity to live life to the fullest and a strong desire to dedicate his life to protecting all that he held dear,” said Christopher F. Carr, a fellow West Pointer and friend. A high-school classmate, C. E. Pope, described Bear as “an American hero in every sense of the word,” and as “one of the most down-to-earth, giving individuals I ever knew. He had a love for his family that was enormous, and he wore his belief in this country on his chest like a badge of honor.” Bear’s sisters—Gina, Becky and Nicole—said in their eulogy, “We know our brother died so that others could live. He died for what he believed in. And let’s just say heaven has its hands full now.”

In the words of the West Point Alma Mater: May it be said, “Well done.”

GUY BARATTIERI MAY HAVE been exceptional among men, but he was typical of a very select group: those who struggle academically at West Point yet persevere to graduate, if barely. Reformers at the Military Academy tried to stamp out the “goat syndrome” in 1978, seeing no good in honoring the bottom academic rank, much less incentivizing the risky effort to attain it. But the cadets who still cheer for the Last Man seem to understand better the peculiar strength of character that undaunted strugglers bring to their endeavors. So today, the spirt of the Goat lives on at West Point.

The legacies of some earlier Last Men have returned to the “rockbound highland home” through their descendants, such as Jenna S. Lafferty. She is a great-great-great-granddaughter of Charles N. Warner, who was the Goat of 1862 (profiled in this volume) and hero of the Battle of Chancellorsville. Jenna entered her plebe year at the Military Academy in 2005 and did somewhat better academically than her illustrious ancestor, finishing as an honor graduate of the Class of 2009. She went on to serve honorably as an intelligence officer with the 170th Infantry Brigade Combat Team in Faryab Province, Afghanistan. Jenna’s family presented Brevet Captain Warner’s 1862 class ring to the Military Academy, where it is currently on display in the library.

In the years since Last in Their Class was published, I have been privileged to speak at the Military Academy on the topic of the Last Man, and also at colleges, historical societies and Civil War Round Tables. I even spoke at West Point’s rival, the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, about that institution’s Anchormen, counterparts to the Goats and generally demonstrating the same bold character and disarming charm. And I have gotten to know people in many walks of life who embody the truth that success in life isn’t determined by academic rank. The stories in this book stand as testimony.