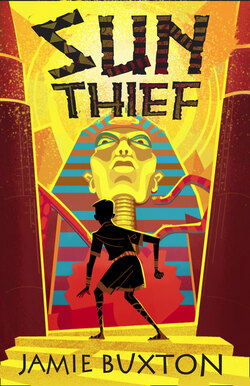

Читать книгу Sun Thief - Jamie Buxton - Страница 13

Оглавление

. . . I’m in trouble.

How much? Quick answer: a heap. Long answer: trouble, trouble with more trouble piled on top and then doubled. Double, double, double trouble. And my mother doesn’t care who knows about it.

She shouts at me so loudly as I walk into the courtyard, with Imi holding tightly on to my hand, that it’s a wonder the walls don’t fall down. We’re late. It’s dark. Anything could have happened. We could have been attacked by robbers, by wild dogs, by lions. And look at the state of Imi: what did I do? Did I try to kill her out of black-hearted jealousy?

It’s a rare busy night and all the drinkers at the inn are nudging each other and shaking their heads, and in case you’re wondering why I don’t run off and hide, my father is gripping my arm so tightly he leaves a bracelet of bruises around it.

And there’s nothing I can say. We got lost in the City of the Dead, the one place I was forbidden to enter? We were trapped there by tomb robbers? That just means more danger for Imi and more trouble for me.

A couple of my father’s cronies start to mutter about bad blood and how I need a good thrashing, when the Quiet Gentleman, who’s been sitting on his own on his usual bench, stands up.

‘You’ve said enough,’ he tells my mother, who shuts up like she’s lost the power of speech.

‘And why don’t you let go of the boy’s arm?’ This to my father, who obeys.

‘And why don’t you step back?’ This to my father’s cronies.

‘There,’ the Quiet Gentleman says, ‘that’s better for everyone. And now we ask the little girl what happened.’ His smile reminds me of a split in an overripe melon.

This is where we get to the bit where you understand why I actually like my sister.

‘I ran away from him,’ Imi says, looking up at the Quiet Gentleman. ‘And I got lost and then I was scared, but he came looking for me and found me and he rescued me from the ghosts and brought me home.’

Perfect answer.

The Quiet Gentleman looks around. As well as the drinkers, a small crowd has gathered at the gate, attracted by my mother’s screeching. He says: ‘All these people want to buy a drink. You’d better get busy, boy.’

I get busy and my parents sell more beer and wine than they have since the shrine became illegal, and I get more tips than I’ve had in my life and a few slaps on the back for being a good boy.

But I don’t tell the Quiet Gentleman about the men who were talking about him in the City of the Dead. I don’t try to warn him. Why? Because if I tell him what I overheard it’ll be like pointing a finger at him and saying tomb robber.

And then he’ll have to kill me.

Next morning I get up early, fetch water, sweep the courtyard, then buy fresh bread and goat’s milk for breakfast.

By the time I’m back, the Quiet Gentleman is sitting in his usual place on the bench. The morning sun’s not too hot and he’s closed his eyes and tilted up his head towards it. He’s found one of my mud animals – a sphinx – and he’s holding it up to the sun as well.

As soon as he hears me, his eyes open sleepily. Whatever I do, wherever I go, he watches me like a dog watches an ant.

When I pass close to him, carrying a heavy leather bucket of water to sluice the kitchen floor, he says: ‘Stop right there, boy.’

I freeze.

‘Look at me.’

Very deliberately I stare past him.

He says: ‘Three questions. You call the innkeeper and his wife mother and father, but you look different. What’s your story?’

‘They found me in the river,’ I say with a shrug.

‘How?’

‘My father used to be a fisherman, too poor for a boat, so he had to throw his nets from the shore. One day he was out fishing late and heard a noise in the bulrushes. He thought it was a kid or maybe a lamb and waded in to get it. It was me. I’d been wrapped in a cloth, put in a little reed boat and sent off down the river. Anyway, he brought me home to my mother and she . . . Well, I don’t know. Maybe they liked me until Imi came along. Maybe she always thought I was a waste of space.’

‘And now he’s an innkeeper. Interesting. Second question: why are you so eager to please him and the woman? All they do is abuse you.’

‘You made them look stupid last night so they’ll take it out on me today,’ I say. ‘I just try to give them fewer excuses.’

‘No one likes a cringer,’ he says.

That hurts like a slap in the face. I don’t say anything, but I feel a hatred for him so deep and strong that I can hardly breathe.

He nods. ‘All right,’ he says in that quiet voice. ‘There’s a bit of life in you, boy. Third question: what’s changed?’

‘What does the master mean?’ I say, adjusting my tone. Submissive, sullen, sarcastic. I know how to annoy guests.

‘The master means what he says,’ he answers right back.

‘Because the master stood up for me last night, I now have money,’ I say. ‘That’s changed.’ I take the tips from my purse and offer them to him. ‘Does the master want a cut?’

‘No.’

‘Then I don’t know what the master means.’

‘The master will tell you, boy. When I arrived at the inn, you were curious about me. But from the moment you walked in last night, you’ve been keeping something from me. So what’s changed?’

I try to hide my shock and start to bluster. ‘I don’t understand the master. I’m only a poor serving boy. The master knows how grateful I was. Am! I’m still grateful. That is what the master sees.’

My dumb act only amuses him. ‘Anyone who can make this –’ he holds up the little mud sphinx ‘– has got more than nothing going on between his ears. It’s not grateful I’m seeing. It’s something else. You went away to pick up your sister. You came back filthy and knowing. Now, how do two little brats get dirty like that? From playing? I don’t think so. From running? Maybe. From hiding?’

The shock must show again because he says: ‘I can see through you like water, boy. Where were you hiding?’

‘The City of the Dead,’ I say, resistance crumbling.

His eyes narrow. ‘Why would a cringer take his sister into the City of the Dead?’

I shake my head. ‘She ran into it on the way back.’

‘Why did she do that?’

‘She said it was a short cut. And she thought it was funny that I was scared and she wasn’t.’

He closes his eyes slowly. It’s like his mind is chewing what I say to get the full flavour of it. Then the eyes open. ‘But last night the little girl said she had been scared. Not of the dead or she would have stayed away. Why is that?’

I feel I’ve just walked into a trap that I knew was there all along. My mouth opens and closes.

‘You tell me if you know so much,’ I just about dare to say.

He shakes his head, then stands, those awful, thick arms heavy by his side.

‘We’ll get to the bottom of it, boy. I’m going for a little stroll, but we’ll talk again when I come back.’ And he walks out of the courtyard.

I’m so scared that I want to be sick.