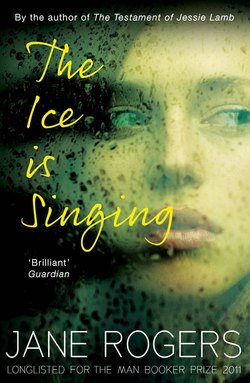

Читать книгу The Ice is Singing - Jane Rogers - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWeds. morning

I am telling stories. In a chipboard cupboard of a room six floors up a cement column, with hot dry air and nylon sheets. The room is so full of electricity that I have adapted to walking slowly, avoiding contacts. My hair crackles, the dry skin on my face is peeling. My lip bleeds.

I am here, not there. There are the twins, Paul and Penny, giggling crying slavering slopping their food sucking their thumbs. Paul sobs in his sleep. Penny moans. My babies who have sucked my breasts and grown in my flesh, pieces of me, my belly my heart.

I am sitting six floors up with a window over the motorway to hills; a five-star view in a one-star room. Snow. Total snow, not London snow. Snow on road ditch hill tree roof cloud car field. I am not –

Not a diary not a journal. Not Marion, not a sniff or spit or print of her. In my cement tower (once doubtless white as an ivory but now yellowing grey as decayed teeth, a tower for my times, the days of ivory – like the golden age – being gone) I sit. Sit, wait, woman in a tower. Like Mariana in her moated grange. No, Rapunzel, gone bald. Stuck up a tower for good.

No games. Here. Nylon sheets, lemon. Two blankets, off white. Nylon quilted bedspread, pink floral. Grey fleck carpet. Woodchip off-white walls. Fitted white-wood wardrobe and shelves, white washbasin, and mirror. Bedside coffee table (supporting lamp) of such generous proportions that this exercise of arm and pen is possible. I sit on the floor under the window, back against the bed, legs outstretched beneath the table. Writing on a new block of A4 ruled feint (wide).

Me. No Penny no Paul No Ruth No Vi no Gareth. Me.

Yes, inescapably me. Not Marion, she says. Not a stiff or– But her sniffs and spits are all over David and Amanda. She has pummelled him into shape – hasn’t she? With her hammy fists, he’s moulded and sticky as dough, paddled with the prints of her flat-edged fingers. Listen.

‘He began to long for a child. Not knowingly, but with a dull subconscious pang of loss.’ He didn’t know (she says). But Marion knows. Mother knows what’s wrong before you know yourself. She names the pain. She identifies it, telling herself that thus it can be remedied, later in the story. Suggesting to herself – comforting herself – deluding herself again – that things follow on, make sense, have remedies.

Perhaps she wanted a good wallow. Nothing like someone else’s troubles. Liberally doused with ketchup, with ‘slow burning love’. Great towering passions, in red and black cloaks. She doesn’t feel secure unless she thinks they’re there.

Instead of real things. Little things, that lurk and move quick and don’t make sense. They resist explanation. They won’t stand still to have metaphors hung round their necks like mayoral chains. Quick, dart, lurk. They’ve gone.

Marion. Whatever she writes. She might as well stop now.