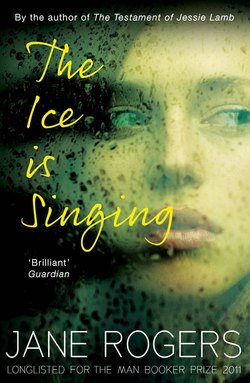

Читать книгу The Ice is Singing - Jane Rogers - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Spinster Daughter

Restraint. But. The clearest thing about her is the house. Kitchen painted bright gloss green and yellow. Should have been like buttercups, like daffodils, sunny. But the colours were too strong and the gloss too shiny, especially the green, and the room had the enclosed and sweaty air of a primary school cloakroom, a public changing-place. Gloss paint for walls is out of fashion now. And the curtains Alice Clough had made were a large and colourful floral print. The floor, of red quarry tiles, was fresh redded and polished every week, and glowed in the light of the brilliant fire which always burned – always, come summer come winter – in the kitchen grate. On the walls a variety of calendars, still supplied by agricultural merchants and purveyors of farm implements (despite the sale of the farmland back in the sixties), showed country scenes, smiling busty girls, and prize-winning shire horses. On the windowsills and sideboard stood orange and mauve gauze flower arrangements, which Alice had made following instructions in a monthly handicrafts magazine. The blanket that she had on the go at the time would be draped over a chair, with multi-coloured tails of wool dangling to the floor.

Where, in this hot bright little kitchen, is the restraint? Except in the form of the room itself. The windows were never opened; fresh air was poison to Alice’s mother and could set her coughing for hours. Layers of cooking smells accumulated beneath the shiny cream ceiling, jostling for airspace: smells of boiling bones and baking custards, simmering jams and roasting potatoes. There was nothing dirty or old about this – the kitchen was spotless. It was just so hot; so full of things; so oppressive, that the milkman when he called to be paid on a cold morning was relieved to back out again into the frosty air, and the doctor rinsing his hands under the sparkling tap would say,

‘The miners’ll thank you for keeping them in work, Miss Clough,’ with a nod towards the high-banked glowing fire.

Added to the heat and smells was frequently an element of steam, rising from sheets and towels draped over an old wooden clothes horse which stood with its arms outstretched to the fire at night, like a large cold guest. The upper sections of the windows were often misted with vapour, and on Mondays the room would be totally enclosed, windows blinded with heavy condensation. Except that Alice would repeatedly clear a smear, at eye level, with her wet red hand, and peer out (at nothing) many times in the course of the day.

Alice Clough worked hard, in a small hot room, amongst garish colours, and was sustained by air that was saturated with smells and heavy with moisture, between gleaming dripping walls and opaque smeared windows.

They lived on the ground floor, she and her mother. Upstairs the house was decaying rapidly. The roof leaked, rafters were rotting, plaster was crumbling away and window panes rattled themselves loose and cracked. Lumps of Victorian furniture, furry with dust, stood in the shadows like stuffed bears. The electric did not work.

Downstairs Ellen had for bedroom the old parlour with its generous tiled fireplace and double window on to the garden. Her room was permanently semi-dark, shrouded from light and more pernicious draughts by heavy velvet curtains. The still air was warmed to oven heat by the ever-burning fire in her grate. Along the wall opposite her bed stood the old three-piece suite, upright but unused, waiting stiffly to resume its rightful position in the room. Alice’s bedroom, a bathroom and scullery completed the downstairs, lived-in part of the house. The scullery, which was cold, was lined with her jams and pickles, and cluttered with broken furniture.

The state of the house was a reflection not only of Ellen’s meanness but also of Alice’s conviction that this state of affairs was temporary. There was no point in repairing the roof, renewing the windows, rewiring or replastering. Because soon Ellen would die, and Alice would sell the house. No point in throwing away good money on it. In fact Ellen’s grip on her purse strings was so vice-like that Alice never had money, either good or bad, to throw at anything. When father died, he left everything to mother. When she died, it would be passed on to Alice and her brother Tom. Each would benefit in turn. And Alice waited her turn.

She had waited when she came back from her nursing in ’45. Nursed her injured brother and said no to Jacko. She had waited while her father’s health declined to invalid state, and waiting, had nursed him. Tom married and left home, and Ellen, suddenly deprived of both her menfolk, threw herself into illness with a determination that should have killed her within months. Alice waited, to nurse her. But Ellen did not die. She continued to be sufficiently ill to need constant nursing, regular doctor’s visits, and a lion’s share of sympathy, for twenty-five years.

Alice did not know it would be twenty-five years. That’s the point about waiting. If you know it’s going to be twenty-five years then you go away and do something else in the meantime. Alice lived the twenty-five years in daily expectation of the time being up. Every activity she embarked upon was temporary. Each decision was provisional. Her own life, ‘for the time being’, was in abeyance; her mother’s demands were more justly pressing, for her mother was about to die.

Alice filled her time, while she was waiting. She nursed her mother with such skill and efficiency that the doctor complimented her regularly. Ellen was turned, and washed, and exercised, and her diet so carefully adhered to, that she was almost entirely free from those secondary discomforts of long-term illness which cause so much distress. She never had a single bedsore, nor was she constipated, and she suffered from secondary infections only on very rare occasions. For years Alice forced her to get up for part of every day, just as she forced herself to cook twice a day – broths, custards, fresh vegetables in season. Ellen pointed out that she had no appetite – none – and that standing and moving was sheer torture to her aching bones. But she knew she owed it to Alice to make an effort, and she hoped Alice appreciated what it was costing her.

She had a hatred of light and fresh air, which Alice’s training had taught her were great aids to healing. When Alice walked in and pulled back the heavy curtains, threw open the window and allowed the clean spring air into the sick-room, Ellen retreated beneath her blankets in paroxysms of coughing, afterwards tearfully accusing Alice of trying to kill her. Eventually Alice was forced to give up, knowing quite clearly that her mother was wrong, and also that her mother knew she was wrong. She believed Ellen took satisfaction not only in behaviour which would increase her own ill health, but also in bullying Alice into abandoning a practice she thought important. Making Alice give things up pleased Ellen. She thrived on it. As she thrived on sickness, and sickness on her.

Alice, growing older, grew bitter. It came on her slowly, as the concertina pressure of years of waiting accumulated behind her to squeeze her forward into a shortened future that could be her own.

Her own life had lasted three years. Until she was eighteen she lived at home with her family. Then (after a battle, but Tom had already gone off to fight and Ellen was so busy being devastated over that, that she didn’t have much energy to spare for Alice) Alice joined a Voluntary Aid Detachment and went south. She went with six other girls volunteering from the neighbourhood, to nurse convalescent troops.

The three years had had to last; the first magical exhausting year in the military hospital, and then her two years at Newcastle General doing her nursing training – broken off by the homecoming of her wounded brother. She had never thought she would still be feeding off those memories, thirty and forty years later. That nothing else at all would have happened. The memories, like old and retouched film, became oddly coloured, unreally bright. She was losing the sense that they had been her own life. As if it has happened to someone else. Another girl with chubby cheeks and long fair hair and a giggly, dimpling laugh. The most important memory, Jacko, had been subjected to so many viewings, so many touchings up, that she hardly knew it now. He was handsome. Kind. Funny. American. A hero; he had joined the British Army before the other Americans came into the war. It didn’t last long – he was nearly better, and was going back to France. But they went for walks when she was off duty, and he kissed her in the fields. The afternoon before he left they lay down in the long grass; it was hot, he tried to – she was trembling, she nearly –

The poor film was so scratched and faded that she was no longer quite sure what had happened. What lingered like a smell was a nauseating sense of physical loss. Her fears had made her reject what her whole body craved.

She had been afraid of getting pregnant. Also afraid of seeming cheap, of losing Jacko. And perhaps she had been right there, because Jacko did care for her. He sent her five letters. And when the war was over he wrote to her from London, saying he was awaiting passage to the US. Could they meet? Tom was bedridden, the pain in his shattered leg still making him delirious from time to time. Alice braved her mother.

‘I have to go to London.’

‘To London? To London? What for?’

‘I want to see – I need to talk to an American friend of mine – before he goes home.’

‘An American?’ Ellen said quietly. ‘My God.’

‘What?’ cried Alice quickly. ‘What’s wrong with it?’

Ellen shook her head.

‘Why shouldn’t I go and see him? I love him. We might get married.’

Ellen snorted. ‘That’s what they all say.’

‘It’s true. Why shouldn’t I go? I’m an adult, aren’t I?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well?’

‘Go. Go on. Go.’

‘I – I was going to go and ask Mrs Munroe if she could give you a hand with Tom – while I’m away.’

‘You needn’t bother.’

‘Look – you can’t manage on your own, you know that.’

‘We’ll manage. If it’s more important to you to go gallivanting off with a Yank than to look after your own flesh and blood that’s nearly died fighting for your freedom, then we can manage, my girl. I’ve got some pride left, I hope. And I’ll tell you something else, madam. If you go, you go for good. I’m not having you back here, after you’ve been off whoring down in London. You go – go on and enjoy yourself – never mind about your brother lying here sweating in pain. Never mind us. I just hope you can sleep nights, in years to come.’

Alice in her innocence saw time as elastic, able to stretch to encompass all good things. She wrote and explained to Jacko. She would see him when her brother was better. Perhaps Tom would come with her and visit him in the States! She would see him soon, and sent him kisses.

There was never time for her to go. And when she became old enough to realize that she should go even though there wasn’t time, it was too late. She looked grey and haggard. Jacko had probably forgotten her, married someone else. Besides, he never had, had he? Asked her to marry him. Only to see him. If she had gone then, she knew – she felt sure. But now it was too late.