Читать книгу Read My Heart: Dorothy Osborne and Sir William Temple, A Love Story in the Age of Revolution - Jane Dunn - Страница 12

CHAPTER FOUR Time nor Accidents Shall not Prevaile

ОглавлениеI will write Every week, and noe misse of letters shall give us any doubts of one another, Time nor accidents shall not prevaile upon our hearts, and if God Almighty please to blesse us, wee will meet the same wee are, or happyer; I will doe all you bid mee, I will pray, and wish and hope, but you must doe soe too then; and bee soe carfull of your self that I may have nothing to reproche you with when you come back.

DOROTHY OSBORNE, letter to William Temple

[11/12 February 1654]

ALTHOUGH TRAVEL ABROAD was accepted as an important part of the education of a young English gentleman of the seventeenth century, a young unmarried lady was denied any such freedom; even travelling at home she was expected to be chaperoned at all times. For her to venture abroad to educate the mind was an almost inconceivable thought. But much more unsettling to the authority of the family, to her reputation and the whole social foundation of their lives was the idea that a young man and woman might meet outside the jurisdiction of their parents’ wishes, free to make their own connections, even to fall in love.

Not only were serendipitous meetings like that of Dorothy and William unorthodox for young people in their station of life, the idea that they themselves could choose whom they wanted to marry on the grounds of personal liking, even love, was considered a short cut to social anarchy, even lunacy. With universal constraints and expectations like this it was remarkable that they should ever have met, let alone discovered how much they really liked each other. Their candour in expressing their feelings in private also belied the carefulness of their public face. Dorothy admitted to William her eccentricity in this: ‘I am apt to speak what I think; and to you have soe accoustumed my self to discover all my heart, that I doe not beleeve twill ever bee in my power to conceal a thought from you.’1

The grip that family and society’s disapproval exerted was hard to shake off. In a later essay when he himself was old, William likened the denial of the heart to a kind of hardening of the arteries that too often accompanied old age: ‘youth naturally most inclined to the better passions; love, desire, ambition, joy,’ he wrote. ‘Age to the worst; avarice, grief, revenge, jealousy, envy, suspicion.’2

Dorothy had youth on her side and laid claim to all those better passions, but it was the unique and shattering effects of civil war that broke the constraints on her life and sprang her into the active universe of men. Although personally strong-minded and individualistic, her intent was always to comply with her family’s and society’s expectations, for she was an intellectual and reflective young woman and not a natural revolutionary. But for the war she would have been safely sequestered at home, visitors vetted by her family, her world narrowed to the view from a casement window. In fact this containment is what she had to return to, but for a while she was almost autonomous, a traveller across the sea – accompanied by a young brother, true, but he more inclined to play the daredevil than the careful chaperone.

As they both set off on their travels, heading on their different journeys towards the Isle of Wight, both Dorothy and William would have had all kinds of prejudice and practical advice ringing in their ears. Travel itself was fraught with danger: horses bolted, coaches regularly overturned, cut-throats ambushed the unwary and boats capsized in terrible seas. Disease and injury of the nastiest kinds were everyday risks with none of the basic palliatives of drugs for pain relief and penicillin for infection, or even a competent medical profession more likely to heal than to harm. The extent of the rule of law was limited and easily corrupted, and dark things happened under a foreign sun when the traveller’s fate would be known to no one.

As William Temple began his adventures for education and pleasure, Dorothy Osborne was propelled by very different circumstances into hers. Travel was hazardous, but it was considered particularly so if you were female. One problem was the necessity for a woman of keeping her public reputation spotless while inevitably attracting the male gaze, with all its hopeful delusions.

Lord Savile, in his Worldly Counsel to a Daughter, a more limited manual than Osborne’s Advice to a Son, was kindly and apologetic at the manifest unfairnesses of woman’s lot, yet careful not to encourage any daughter of his, or anyone else’s, to challenge the sacred status quo. He pointed out that innocent friendliness in a young woman might be misrepresented by both opportunistic men, full of vanity and desire, and women eager to make themselves appear more virtuous by slandering the virtue of their sisters, ‘therefore, nothing is with more care to be avoided than such a kind of civility as may be mistaken for invitation’. The onus was very much upon the young woman who had always to be polite while continually on guard lest her behaviour call forth misunderstanding and shame. She had to cultivate ‘a way of living that may prevent all coarse railleries or unmannerly freedoms; looks that forbid without rudeness, and oblige without invitation, or leaving room for the saucy inferences men’s vanity suggesteth to them upon the least encouragements’.3

Dorothy was often chided by William during their courtship for what he considered her excessive care for her good reputation and concern at what the world thought of her. With advice like this, it was little wonder that young women of good breeding felt that strict and suspicious eyes were ever upon them. A conscientious young woman’s behaviour and conversation had to be completely lacking in impetuousity and candour. It seemed humour also was a lurking danger. Gravity of demeanour at all times was the goal, for smiling too much (‘fools being always painted in that posture’) and – honour forbid – laughing out loud made even the moderate Lord Savile announce ‘few things are more offensive’.4 Certainly a woman was not meant to enjoy the society of anyone of the opposite sex except through the contrivance of family members, with a regard always to maintaining her honour and achieving an advantageous marriage.

After Dorothy and William’s fateful meeting on the Isle of Wight in 1648, they spent about a month together at St Malo, no doubt mostly chaperoned by Dorothy’s brother Robin, as travelling companions and explorers, both of the town and surrounding countryside, and more personally of their own new experiences and feelings. William would have met Sir Peter Osborne there, aged, unwell and in exile. Like the Temple family, the Osbornes were frank about their insistence that their children marry for money. Both Sir Peter Osborne and Sir John Temple were implacably set against any suggestion that Dorothy and William might wish to marry; rather it was a self-evident truth that their children had the more pressing duty to find a spouse with a healthy fortune to maintain the family’s social status and material security. For a short while neither father suspected the truth.

St Malo was an ancient walled city by the sea, at this time one of France’s most important ports. Yet it retained its defiant and independent spirit as the base for much of the notorious piracy and smuggling carried on off its rocky and intricate coast. This black money brought great wealth to the town and financed the building of some magnificent houses. There was much to explore either within the walls in the twisting narrow alleyways or on the heather-covered cliffs that dropped to the boiling surf below.

These days of happy discovery were abruptly terminated when William’s father heard of his son’s delayed progress, and the alarming reason for it. When Sir John Temple ordered William to extricate himself from this young woman and her dispossessed family and continue his journey into France, there was no doubt that William, at twenty, would obey. The impact of this wrench from his newfound love can only be conjectured but he wrote, during the years of their enforced separation, something that implied resentment at parental power and a pained resignation to the habit of filial submission: ‘for the most part, parents of all people know their children the least, so constraind are wee in our demanours towards them by our respect, and an awfull sense of their arbitrary power over us, wch though first printed in us in our childish age, yet yeares of discretion seldome wholly weare out’. As a young man he thought no amount of kindness could overcome the traditional gulf between parents and their children (as parents themselves, he and Dorothy strove to overcome such traditions), but freedom and confidence thrived between friends, he believed, implying a close friend (i.e. a spouse) mattered as much as any blood relation: ‘for kindred are friends chosen to our hands’.5

Dorothy made an equally bleak point in one of her early surviving letters in which she declared that many parents, taking for granted that their children refused anything chosen for them as a matter of course, ‘take up another [stance] of denyeing theire Children all they Chuse for themselv’s’.6

As William reluctantly travelled on to Paris, Dorothy remained with her father and youngest brother, and possibly her mother and other brothers too, at St Malo, hoping to negotiate a return to their home at Chicksands. Five years before, at the height of the first civil war, it had been ordered in parliament ‘that the Estate of Sir Peter Osborne, in the counties of Huntingdon, Bedford or elsewhere, and likewise his Office, be sequestred; to be employed for the Service of the Commonwealth’.7 Towards the end of 1648, however, peace negotiations between parliament and Charles I, in captivity in Carisbrooke Castle, were stumbling to some kind of conclusion. There was panic and confusion as half the country feared the king would be reinstated, their suffering having gained them nothing, while the other half rejoiced in a possible return to the status quo with Charles on his throne again and the hierarchies of Church and state comfortingly restored.

Loyal parliamentarians Lucy and her husband Colonel Hutchinson were in the midst of this turmoil. The negotiations, she wrote, ‘gave heart to the vanquished Cavaliers and such courage to the captive King that it hardened him and them to their ruin. This on the other side so frightened all the honest people that it made them as violent in their zeal to pull down, as the others were in their madness to restore, this kingly idol.’8

Revolution was in the air and, to general alarm, suddenly the New Model Army intervened in a straightforward military coup, taking control of the king, thereby pre-empting any further negotiations, and purging parliament of sympathisers. About 140 of the more moderate members of the Long Parliament were prevented from sitting, Sir John Temple among them. Only the radical or malleable remnants survived the vetting, 156 in all, and they became known for ever as the ‘Rump Parliament’. The king’s days were now numbered.

Dorothy and her family in France were part of an expatriate community who, away from the heat of the struggle, were subject to the general hysteria of speculation and wild rumour, brought across the Channel by letter and word of mouth, reporting the rapidly changing state at home. William was also in France, but by this time separated from Dorothy and alone in Paris. Revolution was in the air there too. ‘I was in Paris at that time,’ he wrote, referring to January 1649, ‘when it was beseig’d by the King* and betray’d by the Parliament, when the Archduke Leopoldus advanced farr into France with a powerfull army, fear’d by one, suspected by another, and invited by a third.’9

It was an alarming but exciting time to be at the centre of France’s own more half-hearted version of civil war, the Fronde,† when not much blood was spilt but a great deal of debate and violent protest dominated the political scene. The Paris parlement had refused to accept new taxes and were complaining about the old, attempting to limit the king’s power. When the increasingly hated Cardinal Mazarin‡ ordered the arrest of the leaders at the end of a long hot summer, there was rioting on the streets and out came the barricades. The court was forced to release the members of parlement and fled the city. Parlement’s victory was sealed and temporary order restored only by the following spring. Having left one kind of turmoil at home, William was embroiled in another, but was not in the mood to let that cramp his youthful style. At some time he met up with a friend, a cousin of Dorothy’s, Sir Thomas Osborne,* and reported their good times in a later letter to his father: ‘We were great companions when we were both together young travelers and tennis-players in France.’10

It was also while he was in Paris in its rebellious mood that William discovered the essays of Montaigne† and perhaps even came across some of the French avant-garde intellectuals of the time. The most contentious were a group called the Libertins, among them Guy Patin, a scholar and rector of the Sorbonne medical school, and François de la Mothe le Vayer, the writer and tutor to the dauphin, who pursued Montaigne’s sceptical philosophies to more radical ends, questioning even basic religious tenets. Certainly from the writings of Montaigne and from the intellectual energy in Paris at the time – perhaps even the company of these controversial philosophers – William learned to enjoy a distinct freedom of thought and action that reinforced his natural independence and incorruptibility in later political life.

Just across the Channel, events were gathering apace. By January 1649 in London the newly sifted parliament had passed the resolutions that sidelined a less compliant House of Lords, allowing the Commons to ensure the trial of the king could proceed. There was terrific nervousness at home; even the most fiery of republicans was not sure of the legality of any such court. In a further eerie echo of the fate of his grandmother, Mary Queen of Scots, Charles was brought hastily to trial, all the while insisting that the court had no legality or authority over him. On 20 January 1649 he appeared before his accusers in the great hall at Westminster. Like his grandmother too he had dressed for full theatrical effect, his diamond-encrusted Order of the Star of the Garter and of St George glittering majestically against the sombre inky black of his clothes. Charles was visibly contemptuous of the cobbled-together court and did not even deign to answer the charges against him, that he had intended to rule with unlimited and tyrannical power and had levied war against his parliament and people. He refused to cooperate, rejecting the proceedings out of hand as manifestly illegal.

All those involved were fraught with anxieties and fear at the gravity of what they had embarked on. As the tragedy gained its own momentum, God was fervently addressed from all sides and petitioned for guidance, His authority invoked to legitimise every action. Through the fog of these doubts Cromwell strode to the fore, his clarity and determination driving through a finale of awesome significance. God’s work was being done, he assured the doubters, and they were all His chosen instruments. It was clear to him that Charles had broken his contract with his people and he had to die. His charismatic certainty steadied their nerves.

The death sentence declared the king a tyrant, traitor, murderer and public enemy of the nation. There were frantic attempts to save his life. From France, Charles’s queen Henrietta Maria had been busy in exile trying to rally international support for her husband. Louis XIV, a boy king who was yet to grow into his pomp as the embodiment of absolute monarchy, now sent personal letters to both Cromwell and General Fairfax pleading for their king’s life. The States-General of the Netherlands also added their weight, all to no avail.

Charles I went to his death in the bitter cold of 30 January 1649. He walked from St James’s Palace to Whitehall, his place of execution. Grave and unrepentant, he faced what he and many others considered judicial murder with dignity and fortitude. As his head was severed from his body, the crowd who had waited all morning in the freezing air let out a deep and terrible groan, the like of which one witness said he hoped never to hear again. Charles’s uncompromising stand, the arrogance and misjudgements of his rule, the corrosive harm of the previous six years of civil wars, had made this dreadful act of regicide inevitable, perhaps even necessary, but there were few who could unequivocally claim it was just. There was a possibly apocryphal story passed on to the poet Alexander Pope, born some forty years later, that Cromwell visited the king’s coffin incognito that fateful night and, gazing down on the embalmed corpse, the head now reunited with the body and sewn on at the neck, was heard to mutter ‘cruel necessity’,11 in rueful recognition of the truth.

For the first time, the country was without a king. The Prince of Wales, in exile in The Hague, was proclaimed Charles II but by the early spring the Rump Parliament had abolished the monarchy and the House of Lords. England was declared a commonwealth with all authority vested in the Commons. The brutal suppression of the Irish rebellion continued through the summer with particularly gruesome massacres at Drogheda and Wexford and the following year, 1650, saw the Scottish royalist resistance broken up by parliamentarian forces. Slowly the bloodshed was being brought to an end and life returned to a new kind of normality.

Most important for the Osborne family in unhappy exile in St Malo was the deal they managed to negotiate with the new government whereby they were allowed to return to their estate at Chicksands on the payment of a huge fine, possibly as much as £10,000 (more than a million by today’s value). This concession might have been in part due to some helpful intervention from Lady Osborne’s brother, the talented garden planner and member of parliament Sir John Danvers. He had become one of Cromwell’s loyal colleagues who served on the commission to try the king and, unlike many, had not baulked at putting his signature to the infamous death warrant. In February 1649 he was appointed one of the forty councillors of state of the new commonwealth, a position he kept until its dissolution in 1653. Dorothy and her mother had stayed with him in his house in Chelsea when she was younger and it is likely he would have exerted whatever influence he could to have their ancestral home restored to them at whatever cost.

So Dorothy and her family returned to Bedfordshire, their lives completely changed and their prospects dimmed. Dorothy’s father was aged and unwell and her mother exhausted by the heavy toll of the last few years of exile, impoverishment and uncertainty. She would only live for another year or so, dying, aged sixty-one, in 1651.

For Dorothy, return to the family home was a mixed blessing. Once again she was subject to the demands made on a dutiful unmarried daughter. After her mother’s death the organisation of the household fell to her, as did the care and companionship of her father. Her favourite brother Robin, who had shared her adventures on the Isle of Wight, was still around and unmarried, as was Henry, eleven years her senior. As men they could come and go at will. Her only sister Elizabeth, the eldest of the family, had married at the age of twenty-six and, after just six years of marriage, died in 1642, before the first civil war. Dorothy was only fifteen at the time and remembered her as a clever bookish girl, cut down far too young, perhaps by puerperal fever, that scourge of childbearing women: ‘my Sister whoe (I may tell you too and you will not think it Vanity in mee) had a great [deale] of witt and was thought to write as well as most women in England’.12 Dorothy’s eldest brother John had also married and appeared occasionally at Chicksands, the estate he was to inherit on their father’s death.

Dorothy professed herself unconcerned at the loss of her family’s fortune: ‘I have seen my fathers [estate] reduced [from] better then £4000 to not £400 a yeare and I thank god I never felt the change in any thing that I thought necessary; I never wanted nor am confident I never shall.’13 This was brave talk, for the family’s impoverishment made her marriage to a man of good fortune all the more pressing. The family matchmakers increased their efforts: Dorothy appeared to entertain their ideas but in fact merely procrastinated, prevaricated and in the last resort refused. She found her seclusion on the family estate increasingly tedious. Paying visits to elderly neighbours and keeping all talk small had limited appeal when she had been exposed to adventure and love. ‘I am growne soe dull with liveing in [Chicksands] (for I am not willing to confess that I was always soe),’14 she admitted.

As a young woman, Dorothy chose to try to live a good life, and while she was unmarried and waiting on her family’s needs this was inevitably a dull one too. She attempted to reconcile her own conduct with the highest standards of her family’s expectations and the precepts of the Bible. She turned to the religious writer Jeremy Taylor, ‘whose devote you must know I am’,15 for his meditations on how to live a useful Christian life. Yet Taylor, in urging a lofty disregard for public opinion, ‘he that would have his virtue published, studies not virtue, but glory’,16 accepted that women’s lives were more constrained. Dorothy, like every other young woman of her time, felt she had to be careful of her reputation. Her and her family’s honour, her marriage prospects, her place in society, all depended on it. She explained this rather defensively in a letter to William Temple: ‘Posibly it is a weaknesse in mee, to ayme at the worlds Esteem as if I could not bee happy without it; but there are certaine things that custom has made Almost of Absolute necessity, and reputation I take to bee one of those.’17

As an emotionally impetuous young man living with greater freedom of conduct than any young woman of his time, William might have wished that Dorothy was more reckless but in fact she was merely expressing a cast-iron truth that most other young unmarried women in her position had learned from the cradle. Lady Halkett, who was to live an unusually adventurous adult life, was equally obedient and careful while young to avoid accusations of ‘any immodesty, either in thought or behavier … so scrupulous I was of giving any occation to speake of mee, as I know they did of others’.18

The social and moral structures of men’s and women’s lives were based on the teaching and traditions of Christian religion and to a lesser extent the philosophy of the classical authors of Greece and Rome. The Church’s view of women was well established and deeply embedded in society’s expectations of human behaviour. The Bible provided the authority. It was read daily and studied closely, making depressing reading for any young woman seeking a view of herself in the larger world. In the Old Testament woman was a mere afterthought of creation. Apart from rare and shining examples, like the wise judge Deborah and the beneficent Queen of Sheba, they had little significance beyond being subjects in marriage and mothers of men. When it reared its head at all, female energy was more often than not duplicitous, contaminatory and dark.

The poet Anne Finch,* of a younger generation than Dorothy, still smarted under the limited expectations for girls, comparing the current generation unfavourably to the paragon Deborah:

A Woman here, leads fainting Israel on,

She fights, she wins, she tryumphs with a song,

devout, Majestick, for the subject fitt,

And far above her arms [military might], exalts her witt,

Then, to the peacefull, shady Palm withdraws,

And rules the rescu’d Nation with her Laws.

How are we fal’n, fal’n by mistaken rules?

Debarr’d from all improve-ments of the mind,

And to be dull, expected and dessigned;

… For groves of Lawrell [worldly triumphs], thou wert

never meant;

Be dark enough thy shades, and be thou there content.19

A thoughtful girl’s reading of the classics in search of images of female creativity or autonomy was almost as unedifying. Unless they were iconic queens such as the incomparable Cleopatra, women of antiquity were subject to even more containment than their seventeenth-century English counterparts. The main role of Greek and Roman women was as bearers of legitimate children and so their sexuality was monitored and feared. Women had to be tamed, instructed and watched. Traditionally they were expected to be silent and invisible, content to live in the shadows, their virtues of a passive and domestic kind.

Dorothy had certainly grown up unquestioning in her belief in God and duty to her parents, expecting to obey them without demur, particularly in the crucial matter of whom she would marry, and wary of drawing any attention to herself. There was more than an echo down the centuries of the classical Greek ideal: that a woman’s name should not be mentioned in public unless she was dead, or of ill repute, where ‘glory for a woman was defined in Thucydides’s funeral speech of Pericles as “not to be spoken of in praise or blame”’.20 The necessity of self-effacement and public invisibility was accepted by women generally, regardless of their intellectual or political backgrounds. The radical republican Lucy Hutchinson, brought up by doting parents to believe she was marked out for pre-eminence, insisted – even as she hoped for publication of her own translation of Lucretius – that a woman’s ‘more becoming virtue is silence’.21

The Duchess of Newcastle was another near contemporary of Dorothy’s but she was one of the rare women of her age who refused to accept such constraints on her sex. Her larger than life persona, however, and her effrontery in publishing her poems and opinions with such abandon attracted violent verbal assaults on her character and sanity. The cavalier poet Richard Lovelace* inserted into a satire, on republican literary patronage, a particularly harsh attack on the temerity of women writers, possibly aimed specifically at the duchess herself, whose verses were published three years prior to this poem’s composition:

… behold basely deposed men,

Justled from the Prerog’tive of their Bed,

Whilst wives are per’wig’d with their husbands head.

Each snatched the male quill from his faint hand

And must both nobler write and understand,

He to her fury the soft plume doth bow,

O Pen, nere truely justly slit till now!

Now as her self a Poem she doth dresse,

Ands curls a Line as she would so a tresse;

Powders a Sonnet as she does her hair,

Then prostitutes them both to publick Aire.22

It was no surprise that even someone as courageous and individual as the Duchess of Newcastle should show some trepidation at breaking this taboo, addressing the female readers of her first book of poems published in 1653 with these words: ‘Condemn me not as a dishonour of your sex, for setting forth this work; for it is harmless and free from all dishonesty; I will not say from vanity, for that is so natural to our sex as it were unnatural not to be so.’23

As a young woman, Dorothy Osborne was intrigued by the duchess’s celebrity, a little in awe of her courage even, for Dorothy too had a love and talent for writing, owned strong opinions and was acutely perceptive of human character. Eager as she was to read the newly published poems (this was the first book of English poems to be deliberately published by a woman under her own name), Dorothy recoiled from the exposure to scorn and ridicule that such behaviour in a woman attracted. And she joined the general chorus of disapproval: ‘there are many soberer People in Bedlam,’24 she declared. Perhaps the harshness of this comment had something to do with the subconscious desire of an avid reader and natural writer who could not even allow herself to dream that she could share her talents with an audience of more than one?

Writing in the next generation, Anne Finch, who did publish her poems late in her life, knew full well the way such presumption was viewed:

Alas! a woman that attempts the pen,

Such an intruder on the rights of men,

Such a presumptuous Creature, is esteem’d,

The fault, can by no vertue be redeem’d.

They tell us, we mistake our sex and way;

Good breeding, fassion, dancing, dressing, play

Are the accomplishments we shou’d desire;

To write, or read, or think, or to enquire

Wou’d cloud our beauty, and exaust our time;

And interrupt the Conquests of our prime;

Whilst the dull mannage, of a servile house

Is held by some, our utmost art, and use.25

Secluded in the countryside, Dorothy cared for her ailing father, endured the social rituals of her neighbours and read volume upon volume of French romances. The highlight of her days and the only, but fundamental, defiance of her fate was her secret correspondence with William Temple. In this Dorothy engaged in the creative project of her life, one that absorbed her thoughts and called forth every emotion. Through their letters they created a subversive world in which they could explore each other’s ideas and feelings, indulge in dreams of a future together and exorcise their fears. Dorothy’s pleasure in the exercise of her art is evident, and she had no more important goal than to keep William faithful to her and determine her own destiny through the charm and brilliance of her letters.

William and Dorothy started writing to each other from the time they were first parted in the later months of 1648 when they were both in France. Martha, William’s younger sister, wrote that he spent two years in Paris and then exploring the rest of the country, by the end of which time he was completely fluent in French. His days drifted by pleasantly enough, playing tennis, visiting other exiles, looking at chateaux and gardens, reading Montaigne’s essays, practising his own writing style and thinking of love. He returned to England for a short while, when Dorothy and her family were also once more resident on the family estate at Chicksands, possibly managing a quick meeting with her then, before he ‘made another Journey into Holland, Germany, & Flanders, where he grew as perfect a Master of Spanish’.26

The surviving letters date from Christmas Eve 1652. It is from this moment that Dorothy’s emphatic and individual voice is suddenly heard. The distant whisperings, speculation and snatches of commentary on their thoughts and lives become clear stereophonic sound as Dorothy, and the echo of William in response, speaks with startling frankness and clarity. The three and a half centuries that separate them from their readers dissolve in the reading, so recognisable and unchanging are the human feelings and perceptions she described. This is the voice even her contemporaries recognised as remarkable, the voice Macaulay fell in love with, of which Virginia Woolf longed to hear more: the voice that has earned its modest writer an unassailable eminence in seventeenth-century literature.

Only the last two years of their correspondence survived, one letter of his and the rest all on Dorothy’s side, but her letters are so responsive to his unseen replies that the ebb and flow of their conversation is clear and present as we read. As William’s sister recognised, the reversals of fortune, much of it detailed in these letters, made their courtship a riveting drama in itself. In order for their love to defy the world and finally triumph, they endured years of subterfuge, secret communication, reliance on go-betweens, stand-up arguments against familial authority, subtle evasions and downright refusals of alternative suitors. The progress of their relationship is revealed in this extraordinary collection of love letters.

As artefacts they are remarkable enough, beautifully preserved by Dorothy’s family over the years and now cared for by the manuscript department at the British Library. Most of the letters are written on paper about A4 size folded in two and with every margin, any spare inch, covered by Dorothy’s elegant, looping script. But it is what they contain that makes them exceptional: frank and conversational in style, the writer’s character and spirit are clear in the confiding voice that ranges widely over daily life and desires, social expectations, and a cavalcade of lovers, family and friends. Sharp, intelligent, full of humour, it is as if Dorothy sits talking beside us. This was exactly the effect she sought to have on William, for these letters were the only way that she could communicate with him through their years of separation, keeping him bound to her and believing in their shared dream.

Dorothy’s first extant letter is a reply to one by William, written on his return to England and after a lengthy gap in their communication. He had previously wagered £10 that she would marry someone other than him and had written, claiming his prize in an attempt to discover obliquely if she remained unattached, even still harbouring warm feelings for him. This was an early indication of his exuberant gambling nature for his bet, at the equivalent of more than £1,000, was significant for a young man who had only just finished his student days. He referred to himself as her ‘Old Servant’, ‘servant’ being the term she and her friends used to refer to anyone actively courting another, or being themselves courted. This was a fishing letter that could not have made his romantic intent more clear.

This was all Dorothy had been waiting for. William had been silent for so long, she had feared he had forgotten her. In her lonely fastness in the country, tending to her father and fending off the suitors pressed on her by her family, his longed-for letter arrived unannounced, revealing clearly his continued interest. All her unexpressed intelligence and pent-up feelings suddenly had a focus again. The brilliance and intensity of her letters expressed this force of emotion and her longing for a soulmate to whom she could talk of the things that really mattered. Later, once she was married, William and others complained that Dorothy’s letters lacked the passion and energy of these written during her courtship. How could they not? These letters were most importantly her means of enchantment, the only recourse she had to seduce his heart and keep him faithful through the long years of enforced separation.

At first her response was careful and controlled. Her handwriting is at its most elegantly formal and constrained. None of her subsequent letters, when she was confident of his feelings, was quite so neatly and carefully written. A great deal of thought has gone into her reply and Dorothy’s answer is masterly in its covert disclosure of her pleasure in hearing from him again, her delight that he still seems to care, the constancy of her feelings and her continuing unmarried state. Despite the fundamental frankness and honesty, her style is full of subtle charm and flirtatious teasing. His revelation of his interest in her had restored her power. She started as she meant to continue, with the upper hand:

Sir

You may please to Lett my Old Servant (as you call him) know, that I confesse I owe much to his merritts, and the many Obligations his kindenesse and Civility’s has layde upon mee. But for the ten poundes hee claims, it is not yett due, and I think you may do well (as a freind) to perswade him to putt it in the Number of his desperate debts, for ’tis a very uncertaine one [she is unlikely to claim it, i.e. marry]. In all things else pray as I am his Servant.

And now Sir let mee tell you that I am extreamly glad (whoesoever gave you the Occasion) to heare from you, since (without complement [without being merely courteous]) there are very few Person’s in the world I am more concer’d in. To finde that you have overcome your longe Journy that you are well, and in a place where it is posible for mee to see you, is a sattisfaction, as I whoe have not bin used to many, may bee allowed to doubt of. Yet I will hope my Ey’s doe not deceive mee, and that I have not forgott to reade. But if you please to Confirme it to mee by another, you know how to dirrect it, for I am where I was, still the same, and alwayes Your humble Servant27

Her request that he write again to reassure her and her signing off ‘for I am where I was, still the same, and alwayes Your humble Servant’ is eloquent of how nothing for her has changed since their last passionate meeting and, she implied, nothing would change, however many eligible suitors, however great the familial pressure. William himself may have had his sexual adventures as a young man abroad, but his heart too had remained constant over the last four years, despite the competing charms of young women with greater fortunes promoted by his family. His sister Martha recalled Dorothy’s and William’s single-minded commitment to each other over the years, to the confounding of some of their friends and all their family, the general thought being that they were negligent of their duty to marry well and disrespectful to their parents: ‘soe long a persuit, though against the consent of most of her friends, & dissatisfaction of some of his, it haveing occasion’d his refusall of a very great fortune when his Famely was most in want of it, as she had done of many considerable offers of great Estates & Famelies’.28

This first letter, tantalisingly revealing and yet concealing so much, had the desired effect on William’s febrile emotions. His answer threw caution to the winds and his professions of affection transformed Dorothy’s confidence. She was emboldened enough to scold him in the next for his neglect in not calling in to see her secretly on his recent trip to Bedford, when he had blamed his horse’s sudden lameness: ‘Is it posible that you came soe neer mee at Bedford and would not see mee, seriously I should never have beleeved it from another. Would your horse had lost all his legg’s instead of a hoofe, that hee might not have bin able to carry you further, and you, somthing that you vallewed extreamly and could not hope to finde any where but at Chicksands. I could wish you a thousand little mischances I am soe angry with you.’29 She was dismayed too by the length of his recent absence and the infrequency of his letters: ‘for God sake lett mee aske you what you have done all this while you have bin away[?] what you mett with in holland that could keep you there soe long[?] why you went noe further, and, why I was not to know you went so farr[?]’30

Perhaps in answer to this William wrote a letter to her, which he embedded in the translated and reworked French romances he sent to her during their separation. They were a way of expressing his frustrated feelings for her, he told Dorothy, and a cartharsis too, for contemplating the miseries of others put his own suffering into perspective:

I remember you have asked me what I did[,] how past my time when I was last abroad. such scribling as this will give you account of a great deal ont. I lett no sad unfortunate storys scape mee but I would tell um over at large and in as feeling a manner as I could, in hopes that the compassion of others misfortunes might diminish the ressentment of my owne. besides twas a vent for my passion, all I made others say was what I should have said myself to you upon the like occasion. you will in this find a letter that was meant for you.31

He entitled the collection of stories, A True Romance, or the Disastrous Chances of Love and Fortune, with more than an eye to his own much impeded love affair with Dorothy. William then added a dedicatory letter, quite obviously written to Dorothy about their own emotional plight. His conversational writing style, so valued in his later essays, was already evident. Although this letter was formal, as there was a chance that the collection of romances would be read by others, it was remarkably simple and straightforward for someone with the emotional exuberance of youth, writing at a time when grandiose prose style was still admired. This was a rare letter in his youthful voice to his young love and worth quoting extensively as it transmitted something of his character and energy, setting his epistolary presence beside hers. He started by offering her his heart and his efforts at creative story-telling, diminished, he believed, by his all-consuming love for her:

To My Lady

Madame

Having so good a title to my heart you may justly lay claime to all that comes from it, theese fruits I know will not bee worth your owning for alas what can bee expected from so barren a soile as that must needs bee having been scorched up with those flames wch your eys have long since kindled in it.

He added that the story of the viccissitudes of their love was more than a match for the ‘tragicall storys’ that follow. But it would take too long, was too painful to recall and it had no end, ‘should I heer trace over all the wandring steps of an unfortunate passion wch has so long and so variously tormented me … Tis not heer my intention to publish a secrett or entertain you with what you are already so well acquainted [i.e. their own love story] tis onely to tell you the occasion that brought thees storys into the frame wherein now you see them.’ William then admits his painful longing for her presence and inability to endure this long separation:

‘Would I could doe it without calling to mind the pains of that taedious absence, wch I thought never would have ended but with my life, having lasted so much longer then I could ever figure to myself a possibility of living without you. How slowly the lame minutes of that time past away you will easily imagine, and how I was faine by all diversions to lessen the occasions of thinking on you, wch yett cost mee so many sighs as I wonder how they left mee breath enough to serve till my return.’

He continued with an explanation of how the translating and reforming of these tales took his mind off his own misfortunes and gave a voice to his overflowing feelings:

‘I made it the pastime of those lonely houres that my broken sleeps usd each night to leave upon my hands. besides in the expressing of their severall passions I found a vent for my owne, wch if kept in had sure burst mee before now, and shewd you a heart wch you have so wholly taken up that contentment could nere find a room in it since you first came there. I send you thees storys as indeed they are properly yours whose remembrance indited [inspired] whatever is passionate in any line of them.’

William then signed off, dedicating his life to her:

And now Madam I must onely aske for pardon for entitling you to The disastrous chances of Love and Fortune; you will not bee displeasd since I thereby entitle you to my whole life wch hath hitherto been composed of nothing else. but whilst I am yours I can never bee unhappy, and shall alwaies esteem fortune my friend so long as you shall esteem mee Your servant32

In fact this second journey abroad, of which Dorothy had been so keen to hear more, was not spent merely moping for his love and writing melodramatic romances. He also found himself highly impressed by what he found in the Dutch United Provinces, a republic in its heyday, full of prosperous, liberal-minded people who nevertheless lived frugally and with a strong sense of civic duty and pride. This golden age was immortalised by the extraordinary efflorescence of great Dutch painters, among them Vermeer, Rembrandt and van Hoogstraten, whose paintings of secular interiors, serene portraits and domestic scenes of vivid humanity reflected the order and self-confidence of an ascendant nation. William was particularly impressed by how willingly the Dutch paid their taxes and took the kind of pride in their public spaces, transport and buildings that Englishmen took only in their private estates. Brussels also attracted him greatly; still at the centre of the Spanish Netherlands, it was here that he learned Spanish. He suggested to his sister, and probably to Dorothy too, that he was considering a career as a diplomat and should Charles II return to the throne and offer him employment, ‘whenever the Governement was setled agin, he should be soe well pleas’d to serve him in, as being His Resident there [in Brussels]’.33

William’s expansive reply to Dorothy’s letter requesting details of what he had been up to during his prolonged absence abroad, prompted her to divulge just how many rivals for her hand she had had to fend off in his absence. First there was an unidentified suitor ‘that I had little hope of ever shakeing of[f]’ until she persuaded her brother to go and inspect his estate. To Dorothy’s delight the house was found to be in such dire condition that she was able to grasp this as reason enough to decline his offer of marriage. Not long after, she heard that this suitor had been involved in a duel and was either killed or had been the one who had done the killing and therefore had fled.* ‘[Either way] made me glad I had scaped him, and sorry for his misfortune, which in Earnest was the least retourne, his many Civility’s to mee could deserve.’

Her mother’s death, she continued, gave her a brief respite for mourning but then a bossy aunt, most probably Lady Gargrave, asserted her authority and pressed another possible husband on her. Luckily her dowry was considered too meagre for him (he wanted an extra £1,000 from her father: this enraged Dorothy who thought him so detestable that even if her dowry was £1,000 less she considered that too much). Then she introduced to William the suitor she nicknamed ‘the Emperour’ who was to be the subject of a running joke between them: ‘some freinds that had observed a Gravity in my face, which might become an Elderly man’s wife (as they term’d it) and a Mother in Law [step-mother] proposed a Widdower to mee, that had fower daughters, all old enough to be my sister’s.’ To William she pretended that the reputation of this man for intelligence and breeding, as well as his owning a great estate, made her think he might do. ‘But shall I tell you what I thought when I knew him, (you will say nothing on’t) ’twas the vainest, Impertinent, self conceated, Learned, Coxcombe, that ever I saw.’34

This ‘impertinent coxcomb’ was Sir Justinian Isham, a royalist from Northamptonshire who had lent money to Charles I and been imprisoned briefly during the civil wars for his pains. He was forty-two when he sought her hand in marriage and, as Dorothy admitted, a learned gentleman and fellow of Christ’s College, Cambridge, who built an excellent library at his country seat, Lamport Hall. His scholarship, however, impeded his letter-writing style, she believed, and in her explanation she sent a mischievous backhanded compliment to William:

In my Opinion these great Schollers are not the best writer’s, (of Letters I mean, of books perhaps they are) I never had I think but one letter from Sir Jus: but twas worth twenty of any body’s else to make mee sport, it was the most sublime nonsence that In my life I ever read and yet I beleeve hee descended as low as hee could to come neer my weak understanding. twill bee noe Complement after this to say I like your letters in themselv’s, not as they come from one that is not indifferent to mee. But seriously I doe. All Letters mee thinks should bee free and Easy as ones discourse, not studdyed, as an Oration, nor made up of hard words like a Charme.

She went on to explain how frustrating it was when people tried so hard for effect that they obscured meaning, like one gentleman she knew ‘whoe would never say the weather grew cold, but that the Winter began to salute us’.35 Whether this was ‘the Emperour’s’ stylistic weakness she did not say but continued her characterisation of him in subsequent letters: he was over-strict with his poor daughters (and Dorothy surmised would have been with her too if she had become his wife) and ‘keep’s them soe much Prisoners to a Vile house he has in Northamptonshyre, that if once I had but let them loose they and his Learning would have bin sufficient to have made him mad, without my helpe’. She also enjoyed exploring the conceit with William that in marrying Isham she would then offer one of her stepdaughters to him in marriage ‘and ’tis certaine I had proved a most Exelent Mother in Law’.36

Dorothy’s lively descriptions of a colourful list of suitors not only entertained William, they also inevitably impressed him with the competition he was up against and quickened his already urgent desire. She knew this and throughout there was a sense of her playfulness and control. She was relating these stories in the January and February of 1653 but this particular courtship had taken place the previous spring and early summer, as was clear in the laconic entries in her brother Henry’s diary. By the beginning of March 1652, Henry had thought it necessary to prod Sir Justinian Isham into some kind of definite offer. There were various dealings between the two families, and Dorothy’s polite but evasive stance seemed to win out.

William’s young friend, Sir Thomas Osborne, who had been such a good companion to him during his first travels in France, also decided to open marriage negotiations with Dorothy, the girl he had known all his life as his older cousin, aged twenty-five to his twenty-one. This frantic marriage-trading overlapped with the Sir Justinian Isham period. Again brother Henry’s diary recorded meetings between the suitors and their families: letters whizzed back and forth, with Dorothy under pressure but holding her ground. There was some exasperation or misunderstanding and Sir Thomas’s mother, Lady Osborne, broke off negotiations. Dorothy was then removed from her brother-in-law’s London house, where she had been staying, as her favourite niece, Dorothy Peyton, and her stepmother Lady Peyton had contracted smallpox. By 10 April, the dread disease had attacked Thomas Osborne too. All three were to survive but the aftermath of the failed marriage negotiations continued to haunt Dorothy.

Henry’s diary told how the following month the protagonists converged on Aunt Gargrave’s house: first Lady Osborne explained why they had withdrawn; then Dorothy gave her version of events; and finally Sir Thomas related ‘what hee had said to his mother’. In the middle of all these excuses and accusations, Sir Justinian Isham re-entered the fray. Dorothy was isolated and under siege but courageously maintained her resistance. Her despairing brother, usually so matter-of-fact and unemotional in his diary entries, confided on 28 June this heartfelt cry: ‘I vowed a vow to God to say a prayer everie day for my sister and when shee is married to give God thanks that day everie day as long as I lived.’37

Sir Justinian quickly found a more receptive hand in Vere, the daughter of Lord Leigh of Stoneleigh. They married in 1653 and she produced two sons, each of whom inherited their father’s baronetcy. Like the Emperour, Sir Thomas Osborne also married in 1653 although Dorothy had already felt that their relationship as cousins was spoiled by the sour end to their courtship. This affected even his friendship with William, she feared: ‘Sir T. I suppose avoyd’s you as a freind [suitor] of mine, my Brother tells mee they meet somtim’s and have the most adoe to pull of theire hatts to one another that can bee, and never speake. If I were in Towne i’le undertake, hee would venture the being Choaked for want of Aire rather than stirre out of doores, for feare of meeting mee.’38

Little wonder that she retired during the late summer of 1652 to the spa at Epsom, just outside London, to take the waters there. Leaving Chicksands on 16 August, Dorothy was to spend over two weeks drinking the waters daily in hope of a cure. She often referred to how she suffered from melancholy and low or irritable spirits that were commonly called ‘the Spleen’. This time her indisposition was due to ‘a Scurvy Spleen’ with little indication as to what scurvy meant in that context. In a later essay, ‘Of health and Long Life’, William, writing about the fashions in health complaints and various cures, claimed that once every ailment was called the spleen, then it was called the scurvy, so perhaps Dorothy’s doctor was covering all possibilities. It could be that she had a skin disease alongside the depression (the Epsom waters were good for skin complaints), or in fact she might have been using ‘scurvy’ figuratively meaning a sorry or contemptible thing, in this case her depression. She was aware of the fact that some people considered ‘the Spleen’ a largely hysterical condition and therefore wholly feminine, and was shy of naming William’s occasional depressions of spirit as melancholy: ‘I forsaw you would not bee willing to owne a disease, that the severe part of the worlde holde to bee meerly imaginary and affected, and therefore proper only to women.’39

There was no doubt that Dorothy herself considered her symptoms to be real, even ominous. Her brother Henry and his friends had no sensitivity to her feelings and threatened her with imbecility, even madness, as she reported to William: ‘[they] doe soe fright mee with strange story’s of what the S[pleen] will bring mee in time, that I am kept in awe with them like a Childe. They tell mee ’twill not leave mee common sence, that I can hardly bee fitt company for my own dog’s, and that it will ende, either in a stupidnesse that will have mee incapable of any thing, or fill my head with such whim’s as will make mee, rediculous.’40

So concerned was she that she used to dose herself with steel, against William’s advice. This involved immersing a bar of steel in white wine overnight and then drinking the infusion the next morning. The effects were unpleasant: ‘’tis not to be imagin’d how sick it makes mee for an hower or two, and, which is the missery all that time one must be useing some kinde of Exercise’. Such prescribed exercise meant for Dorothy playing shuttlecock with a friend while she felt more and more nauseous. The effects were so extreme, she wrote to William, ‘that every day at ten o clock I am makeing my will, and takeing leave of all my friend’s, you will beleeve you are not forgot then … ’tis worse then dyeing, by the halfe’.41 By the next morning, all the suffering would be worthwhile ‘for Joy that I am well againe’.42

William was not convinced by this treatment, in fact he had little respect for doctors or their cures, and it was obvious from Dorothy’s letters that he would rather she desist. The effects of ‘the Spleen’ interested him and in the same essay on health he gave a description drawn from his personal experience in his own family, together with a very modern analysis of the importance of attitude of mind in maintaining health:

whatever the spleen is, whether a disease of the part so called, or of people that ail something, but they no not what; it is certainly a very ill ingredient into any other disease, and very often dangerous. For, as hope is the sovereign balsam of life, and the best cordial of all distempers both of body and mind; so fear, and regret, and melancholy apprehensions, which are the usual effects of the spleen, with the distractions, disquiets, or at least intranquillity they occasion, are the worst accidents that can attend any diseases; and make them often mortal, which would otherwise pass, and have had but a common course.43

Dorothy returned from Epsom on 4 September 1652 only to find her brother Henry, who was fast becoming the bane of her life, had been nurturing another suitor in her absence, the scholarly Dr Scarborough. To William she admitted her amazement that such a reserved and serious intellectual should have any interest in courtship and marriage: ‘I doe not know him soe well as to give you much of his Character, ’tis a Modest, Melancholy, reserved, man, whose head is so taken up with little Philosophicall Studdy’s, that I admire how I founde a roome there, ’twas sure by Chance.’44 In fact this suitor was to be one of the founders of the Royal Society. Dr (later Sir) Charles Scarborough was a physician and mathematician, eleven years Dorothy’s senior, who was to become eminent as a royal doctor to Charles II, James II and William III. He was so dedicated to research that Dorothy feared that the only way she could ever occupy any part of his thoughts would be by becoming a subject for scientific investigation herself, particularly that aspect of her nature others considered least attractive, like her fits of melancholy.

The pragmatic approach to marrying off one’s daughters was evident in her family well before Dorothy had met William and unhelpfully set her heart on him alone. After the death of her sister Elizabeth, it was considered for a while that her brother-in-law, Sir Thomas Peyton, an excellent royalist gentleman with an estate in Kent, might then marry Dorothy. Both she and Elizabeth had been clever bookish girls with a fine writing style: to the practical and undiscerning they might have seemed interchangeable. Except Dorothy was only fifteen when her sister died and seemed already to hope for more in life than a marriage of convenience, particularly one to a widowed brother-in-law.

Whatever these inchoate plans might have been, Sir Thomas Peyton confounded them all by marrying a woman with a completely opposite temperament to the Osborne girls: Cecelia Swan, the widow of a mayor of London, was ‘of a free Jolly humor, loves cards and company and is never more pleased then when she see’s a great many Others that are soe too’. Dorothy marvelled that her brother-in-law could be such an excellent and contented husband with two such different wives. She explained to William why he briefly considered her as his next wife, and in the process continued her deft and generous character sketch of the second Lady Peyton: ‘His kindenesse to his first wife may give him an Esteem for her Sister [Dorothy herself], but hee [was] too much smitten with this Lady to think of marrying any body else, and seriously I could not blame him, for she had, and has yet, great Lovlinesse in her, she was very handsom and is very good, one may read it in her face at first sight.’45

Her most eminent suitor, and her most surprising given she was of such loyal royalist stock, was Henry Cromwell,* fourth son of Oliver Cromwell, soon to be lord protector. There is no indication as to how these two young people met and their unlikely friendship is a tantalising one. Henry was an exact contemporary of William’s, one year younger than Dorothy and her favourite suitor among the also-rans. He lacked William’s romantic good looks but was a thoroughly amiable, intelligent and capable young man: while William was abroad playing tennis, perfecting his French and pining for love, Henry was in the thick of battle, serving under his father during the latter part of the civil wars.

Dorothy remained friends with him even after their courtship came to nothing and he had married another. She shared with him a love of Irish greyhounds and already owned a bitch he had given her that had belonged to his father. Unlike other ladies of her acquaintance, she eschewed lap dogs for the grandeur of really big breeds and had asked Henry Cromwell to send her from Ireland a male dog, ‘the biggest hee can meet with, ’tis all the beauty of those dogs or of any indeed I think, a Masty [mastiff] is handsomer to mee then the most exact little dog that ever Lady playde withall’.46 When no hound was forthcoming she transferred the request through William to his father Sir John Temple, when he was next in Ireland. Three months later, at the end of September 1653, it was Henry Cromwell who came up with the goods: ‘I must tell you what a present I had made mee today,’ she wrote excitedly to William, ‘two [of] the finest Young Ireish Greyhounds that ere I saw, a Gentelman that serv’s the Generall [Oliver Cromwell] sent them mee they are newly come over and sent for by H. C.’47

Rivalry over which suitor could provide the best dog may have spurred William on to entreat his father to send a dog from Ireland, as previously requested, or in fact he may have sent his own hound to stay with Dorothy at Chicksands when he himself set out for Ireland the following spring, but a Temple greyhound did arrive at Chicksands to compete for Dorothy’s attention with the Cromwell pair. In March, Dorothy wrote to William expressing her care and affection for this new dog and her efforts to protect him from the pack. It is easy to see how her relationship with this dog was used by her as a metaphor for her feelings for William, and her constant defence of him against the malice of his detractors: ‘Your dog is come too, and I have received him with all the Kindnesses that is due to any thinge you sende[,] have deffended him from the Envy and the Mallice of a troupe of greyhounds that used to bee in favour with mee, and hee is soe sencible of my care over him that hee is pleased with nobody else and follow’s mee as if wee had bin of longe acquaintance.’48

There is no letter from William to Dorothy that could tell us what he thought of all these human rivals when he was kept so strictly from her. His one existing letter, written later in their courtship when he had arrived in Ireland on a visit to his father, was passionate, ecstatic and extreme; he vowed he could not live without her and, in the absence of a letter, strove to reassure himself of her love. At this time, judging from her own letters in response to his, there were occasions when he lost confidence in his powers to keep her, feared he did not write such fine letters as others, or thought her less passionately committed to him than he was to her.

William’s sense of frustration at their separation and his powerlessness to effect anything was expressed in his anxiety that Dorothy should not be taken in by young men engaged merely in the pursuit of love, full of pretence and false emotion, ‘one whining in poetry, another groaning in passionate epistles or harangues … how neer it concerns young Ladys in this age to beware of abuses, not to build upon any appearance of a passion wch men learne by rote how to act, and practise almost in all companys where they come’.49 It seemed his fears were frankly and easily expressed to Dorothy and she was quick to console him with her continual longing for him and desire for his happiness: ‘if to know I wish you with mee, pleases you, tis a satisfaction you may always’s have, for I doe it perpetualy, but were it realy in my Power to make you happy, I could not misse being soe my self for I know nothing Else I want towards it.’50

He did describe, however, in one of his early essays, written during these fraught times of separation and uncertainty, the corrosive power of jealousy from what seemed to be personal experience: his style, formal here as befits an essay, would have been much more conversational had this been expressed instead in a letter to Dorothy:

Amongst all those passions wch ride mens soules none so jade and tire them out as envy and jealousy … jealousy is desperate of any cure, all thinges nourish, nothing destroyes it … where this suspicion is once planted, the fondest circumstances serve to encrease it, the clearest eveidences can never root it out; though a man beleeves it is not true yet tis enough that it might have been true … tis the madness of love, the moth of contentment, the wolfe in the brest, the gangreen of the soule the vulture of Tityus still knawing at the heart, tis the ranckest poyson growing out of the richest soile, engender’d of love, but cursed viper, teares out its mothers bowells … tis allwayes searching what it hopes never to find.51

Everything was made far worse by their enforced separation. In absence, rivals grow in the imagination, fantasies become real and love and fear of loss inflate into obsession. There was little reassurance to be had from anyone but each other and their letters assumed enormous significance. But then letters took so long to be delivered that the mood had passed by the time a reply arrived. Most were carried privately by a post boy, whose horse was changed at regular stages along the journey, or by a carrier’s wagon. The charge was based on how many pages were sent. Dorothy’s letters were closely written on every spare margin and corner of her sheet of paper and sometimes finished abruptly when she ran out of space. The cost of sending a letter from Chicksands to London was 2 old pence.* She usually wrote on a Sunday to catch the Monday morning carrier and it arrived that evening or Tuesday morning. William wrote his reply on a Wednesday, or often very early on the Thursday to catch the dawn carrier so that his letter would be in Dorothy’s eager hands by the evening or following Friday morning. Dorothy was so desperate for her precious lifeline to him that sometimes she sent one of the Chicksands’ grooms to meet the courier, fortunately oblivious of the emotional import of what he had to collect. Her relating of this in a letter to William in the spring of 1653 was a tour de force that revealed the unbearable tension of waiting for the object of desire, recalled in the warm glow of possession:

Sir, Iam glad you escaped a beating [from her if he had missed the courier] but in Earnest would it had lighted upon my Brother’s Groome, I think I should have beaten him my self if I had bin able. I have Expected your letter all this day with the Greatest impatience that was posible, and at Last resolved to goe out and meet the fellow, and when I came downe to the stables, I found him come, had sett up his horse, and was sweeping the Stable in great Order. I could not imagin him soe very a beast as to think his horses were to bee served before mee, and therfor was presently struck with an aprehension hee had noe letter for mee, it went Colde to my heart as Ice, and hardly left mee courage enough to aske him the question, but when hee had drawled out that hee thought there was a letter for mee in his bag I quickly made him leave his broome. ’Twas well ’tis a dull fellow [for] hee could not but … have discern’d else that I was strangly overjoyed with it, and Earnest to have it, for though the poor fellow made what hast hee could to unty his bag, I did nothing but chide him for being soe slow. At last I had it, and in Earnest I know not whither an intire diamond of the bignesse on’t would have pleased mee half soe well, if it would, it must bee only out of this consideration that such a Juell would make mee Rich Enough to dispute you with Mrs Cl [a possible wife for him promoted by his father]: and perhaps make your father like mee as well.52

About three weeks later, Dorothy was in even greater need of William’s letters as she sat in vigil by her father’s bed, afraid he might be dying. Exhausted and strained, she vented her disappointment at the scrappy letter she had just received from him, exhorting him to start writing to her earlier instead of leaving it to the last minute. She was exasperated too with his petulant comment that she did not value his letters enough:

But harke you, if you think to scape with sending mee such bits of letters you are mistaken. You say you are often interupted and I believe you, but you must use then to begin to write before you receive mine, and hensoever you have any spare time allow mee some of it. Can you doubt that any thing can make your letters Cheap. In Earnest twas unkindly sayed, and if I could bee angry with you, it should bee for that. Noe Certainly they are, and ever will bee, deare to mee, as that which I receive a huge contentment by … O if you doe not send mee long letters then you are the Cruellest person that can bee. If you love mee you will and if you doe not I shall never love my self.53

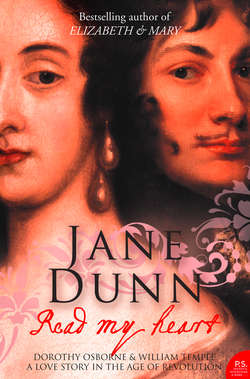

Portraits were also necessary and affecting substitutes for the absent. They were painted and exchanged as important reminders of the loved one’s presence. Interestingly both Dorothy and William, neither of them rich or aristocratic, were to have portraits painted of themselves by some of the greatest artists of the day. In the summer of 1653 William was obviously missing her greatly and had asked for some memento: Dorothy suggested she get a miniature done of herself to send to William to console him in her absence. Nerves were obviously fraying: ‘For god sake doe not complaine soe that you doe not see mee, I beleeve I doe not suffer lesse in’t then you, but tis not to be helpt. If I had a Picture that were fitt for you, you should have it, I have but one that’s any thing like and that’s a great [full size] one, but I will send it some time or other to Cooper or Hoskins,* and have a litle one drawne by it, if I cannot bee in Towne to sitt my selfe.’54

As suitors came and went it was not just William and Dorothy who suffered. Dorothy’s brother Henry, the family member most assiduous about arranging a good marriage for her, many times came close to hysteria. He certainly subjected her to endless probing conversations, tearful reproaches, emotional blackmail and downright bullying in his attempts to undermine her adamant loyalty to William and antipathy to the candidates he steered her way. He once threatened with violence the messenger bringing the mail to Chicksands and periodically searched the house for evidence of letters from Dorothy’s forbidden lover: this accepted violation of her privacy was possibly the reason why only one of William’s letters from this period exists today, for it would seem Dorothy was forced to dispose of them once she had read them. On one occasion she wrote to William that she was unwilling to destroy the letter she had just received: ‘You must pardon mee I could not burn your other letter for my life, I was soe pleased to see I had soe much to reade, & soe sorry I had don soe soone, that I resolved to begin them again and had like to have lost my dinner by it.’55

If in fact Dorothy felt compelled to destroy each of William’s longed-for letters it would have caused great anguish, for they were largely her only contact with him and had an iconic power. The emotional journey they described was the most important of her life and, as her co-conspirator, his was the only reassuring voice in a chorus of ignorance and hostility. For all she knew, their clandestine letters might have been all they would ever have to show for these years of heightened feeling, should their love story end the way the world expected.