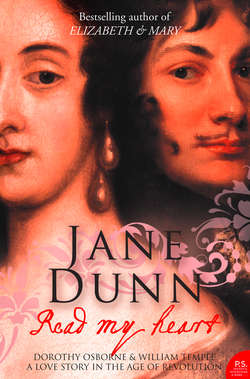

Читать книгу Read My Heart: Dorothy Osborne and Sir William Temple, A Love Story in the Age of Revolution - Jane Dunn - Страница 9

CHAPTER ONE Can There Bee a More Romance Story Than Ours?

ОглавлениеAll Letters mee thinks should bee free and Easy as ones discourse not studdyed, as an Oration, nor made up of hard words like a Charme

DOROTHY OSBORNE [to William Temple, September 1653]

as those Romances are best whch are likest true storys, so are those true storys wch are likest Romances

WILLIAM TEMPLE [to Dorothy Osborne, c.1648–50]

THE ROMANCE BEGAN in the dismal year of 1648. It was much wetter than usual with an English summer full of rain. The crops were spoiled, the animals sickened ‘and Cattell died of a Murrain everywhere’.1 The human population had fared no better. The heritage of Elizabeth I’s reign had been eighty years of peace, the longest such period since the departure of the Romans over twelve centuries before. After this, the outbreak of civil war in 1642 had come as a severe shock. Few had remained unscathed. By the time the crops failed in 1648, the first hostilities of the civil war were over but the bitterness remained. The nightmare of this domestic kind of war was its indistinct firing lines and the fact the enemy was not an alien but a neighbour, brother or friend. The rift lines were complex and deep. Old rivalries and new opportunism added to the murderous confusion of civil war. Waged in the name of opposing interests and ideologies, the pitiful destruction and its bitter aftermath were acted out on the village greens and town squares, in the demesnes of castles and the courtyards of great country houses.

One of the many displaced by war was the young woman, Dorothy Osborne. She was twenty-one and in peaceful times would have been cloistered on her family’s estate in deepest Bedfordshire awaiting an arranged marriage with some eligible minor nobleman or moneyed squire. Instead, she was on the road with her brother Robin, clinging to her seat in a carriage, lurching on the rutted track leading southwards on the first leg of a journey to St Malo in France, where her father waited in exile. Low-spirited, disturbed by the catastrophes that had befallen her family, Dorothy could not know that the adventure was about to begin that would transform her life.

Dorothy’s family, the Osbornes of Chicksands Priory near Bedford, was just one of the many whose lives and fortunes were shaken and dispersed by this war. At its head was Sir Peter Osborne, a cavalier gentleman who had unhesitatingly thrown in his lot with the king when he raised his standard at Nottingham in August 1642. Charles’s challenge to parliament heralded the greatest political and social turmoil in his islands’ history. And Sir Peter, along with the majority of the aristocracy and landed gentry, took up the royalist cause; in the process he was to lose most of what he held dear.

Dorothy was the youngest of the Osborne children, a dark-haired young woman with sorrowful eyes that belied her sharp and witty mind. When war first broke out in 1642 she was barely fifteen and her girlhood from then on was spent, not at home in suspended animation, but caught up in her father’s struggles abroad or as a reluctant guest in other people’s houses. After the rout of the royalist armies in the first civil war, the Osborne estate at Chicksands was sequestered: the family dispossessed was forced to rely on the uncertain hospitality of a series of relations. Being the beggars among family and friends left Dorothy with a defensive pride, ‘for feare of being Pittyed, which of all things I hate’.2

By 1648 two of her surviving four brothers had been killed in the fighting, and circumstances had robbed her of her youthful optimism. Her father had long been absent in Guernsey. He had been suggested as lieutenant governor for the island by his powerful brother-in-law Henry Danvers, Earl of Danby, who had been awarded the governorship for life. To be a royalist lieutenant governor of an island that had declared for the parliamentarians was a bitter fate and Sir Peter and his garrison ended up in a prolonged siege in the harbour fortress of Castle Cornet, abandoned by the royalist high command to face sickness and starvation. Dorothy, along with her mother and remaining brothers, was actively involved in her father’s desperate plight and it was mainly the family’s own personal resources that were used to maintain Sir Peter and his men in their lonely defiance.

Camped out in increasing penury and insecurity at St Malo on the French coast, his family sold the Osborne silver and even their linen in attempts to finance provisions for the starving castle inmates. When their own funds were exhausted, Lady Osborne turned to solicit financial assistance from relations, friends and reluctant officials. Often it had been humiliating and unproductive work. Dorothy had shared much of her mother’s hardships in trying to raise funds and both had endured the shame of begging for help. These years of uncertainty and struggle took their toll on everyone.

Dorothy’s mother, never the most cheerful of women, had lost what spirits and health she had. She explained her misanthropic attitude to her daughter: ‘I have lived to see that it is almost impossible to believe people worse than they are’; adding the bitter warning, ‘and so will you.’ Such a dark view of human nature expressed forcefully to a young woman on the brink of life was a baleful gift from any mother. Lady Osborne also criticised her daughter’s naturally melancholic expression: she considered she looked so doleful that anyone would think she had already endured the worst tragedy possible, needing, her mother claimed, ‘noe tear’s to perswade [show] my trouble, and that I had lookes soe farr beyond them, that were all the friends I had in the world, dead, more could not bee Expected then such a sadnesse in my Ey’s’ [she could not look any sadder].3

So it was that this young woman, whose life had already been forced out of seclusion, set out with her brother Robin in 1648 for France. Dorothy recognised the change these hardships had wrought, how pessimistic and anxious she had become: ‘I was so alterd, from a Cheerful humor that was always’s alike [constant], never over merry, but always pleased, I was growne heavy, and sullen, froward [turned inward] and discomposed.’4 She had little reason to expect some fortunate turn of fate. More likely was fear of further loss to her family, more danger and deaths and the possibility that their home would be lost for ever.

An arranged marriage to some worthy whose fortune would help repair her own was the prescribed goal for a young woman of her class and time. Dorothy had grown up expecting marriage as the only career for a girl, the salvation from a life of dependency and service in the house of some relation or other. But it was marriage as business merger, negotiated by parents. Love, or even liking, was no part of it, although in many such marriages a kind of devoted affection, even passion, would grow. She struggled to convince herself it was a near impossibility to marry for love: ‘a happiness,’ she considered, ‘too great for this world’.5

Dorothy, however, had been exposed also to the more unruly world of the imagination. She was a keen and serious reader. She immersed herself in the wider moral and emotional landscapes offered by the classics and contemporary French romances, most notably those of de Scudéry. These heroic novels of epic length, sometimes running to ten volumes, enjoyed extraordinary appeal during the mid-seventeenth century. Some offered not just emotional adventure but also the delights of escapism by taking home-based women (for their readers were mostly female) on imaginary journeys across the known world.

Despite having her heart and imagination fired with fables of high romance, Dorothy knew her destiny as an Englishwoman from the respectable if newly impoverished gentry lay in a grittier reality. As she and her brother passed through their own war-scarred land they were faced by the hard truth that the conflict was not yet over and the country was becoming an increasingly disorderly and lawless place. Traditions of accepted behaviour and expectation were upended. Authority, from the local gentry landowners to the king, had been fundamentally challenged and law and order were beginning to crumble. Travelling was dangerous at any time, for the roads were rutted tracks and travellers were vulnerable to desperate or vicious men. There was no police force, and justice in a time of war was random and largely absent. In her memoirs Lady Halkett,* a contemporary of Dorothy’s, noted the increase in unprovoked acts of murderous sectarian violence against individuals: ‘there was too many sad examples of [such] att that time, when the devission was betwixt the King and Parliament, for to betray a master or a friend was looked upon as doing God good service.’6

Dorothy recalled later the self-imposed tragedy, witnessed at first hand, of what had become of England, ‘a Country wasted by a Civill warr … Ruin’d and desolated by the long striffe within it to that degree as twill bee usefull to none’.7 Certainly her family’s fortunes and future prospects appeared to be as ruined as the burned houses and dying cattle they passed on their journey south. However destructive civil war was to life, fortune and security, the social upheavals broke open some of the more stifling conventions of a young unmarried woman’s life. Although exposing her to fear and humiliation, the struggle to save her father propelled Dorothy out of Bedfordshire into a wider horizon and a more demanding and active role in the world.

Now she was on the road again: however disheartening the reasons for her journey, whatever the dangers, she was young enough to rise to this newfound freedom and the possibility of adventure. The bustling activity of other travellers was always interesting, the unpredictability of experience exhilarating to a highly perceptive young woman: for Dorothy the small dramas of people’s lives were a constant diversion. She shared her amusement with her brother Robin on the journey, possibly making similar comments to the following, when she noted the extraordinary diminishment wrought by marriage on a male acquaintance whom she had thought destined for greater things. It is as if she is talking to us directly, confiding this piece of mischievous gossip to an inclined ear:

I was surprised to see, a Man that I had knowne soe handsom, soe capable of being made a pretty gentleman … Transformed into the direct shape of a great Boy newly come from scoole. To see him wholly taken up with running on Errand’s for his wife, and teaching her little dog, tricks, and this was the best of him, for when hee was at leasure to talke, hee would suffer noebody Else to doe it, and by what hee sayd, and the noyse hee made, if you had heard it you would have concluded him drunk with joy that hee had a wife and a pack of houndes.8

Dorothy’s analytic, philosophical turn of mind always searched for deeper significance as well as humour in the antics of her fellows. Her conversational letters, full of irony and gossip, showed her striving to do right herself and yet highly entertained by the wrongs done by others. As Dorothy and Robin crossed by ferry to the Isle of Wight to await the boat to France there was much to watch and wonder at. When they eventually arrived at the Rose and Crown Inn they had the added piquancy of being close to the forbidding Norman fortress, Carisbrooke Castle, where Charles I was imprisoned, with all the attendant speculation around his recent incarceration and various attempts at escape and rescue.

Also en route to France was a young man of quite extraordinary good looks and ardent nature. William Temple was only twenty and had evaded most of the bitter legacies and depredations of the civil war. His family were parliamentarians, his father sometime Master of the Rolls in Ireland and a member of parliament there. William was his eldest son and although not dedicated to scholarship was highly intelligent and curious about the world, with an optimistic view of human nature. His easy manners, interest in others and natural charm were so infectious that his sister Martha claimed that on a good day no one, male or female, could resist him. Sent abroad by his father to broaden his education and protect him from the worst of the war at home, William Temple, naturally independent-minded and tolerant, avoided playing his part in the sectarianism that divided families and destroyed lives.

There was nothing, after all, to keep him at home, as his sister later explained: ‘1648 [was] a time so dismal to England, that none but those who were the occasion of those disorders in their Country, could have bin sorry to leave it.’9 William headed first for the Isle of Wight to visit his uncle Sir John Dingley who owned a large estate there. He had another more controversial family member on the island, his cousin Colonel Robert Hammond,* who as the governor of Carisbrooke Castle had the unenviable task of keeping the defeated king confined.

Having lost the first of the civil wars and in fear for his life, Charles I had escaped from Hampton Court in November 1647 but, like his grandmother Mary Queen of Scots nearly eighty years before, had decided against fleeing to France. Instead he turned up on the shores of the Isle of Wight. Taken into captivity in Carisbrooke Castle, Charles’s restive mind turned on schemes of rescue. He was plotting an uprising of the Scots and hoping even for help from the French, encouraged by his queen Henrietta Maria who had sought asylum there.

There has been some speculation that William may have visited his Hammond cousin too and seen the king at this time. If he did see Charles he was not impressed. In a later essay, written in his early twenties, he wrote disparagingly about how disappointed he was with the Archduke Leopold† in the flesh after his ‘towring titles gave mee occasion to draw his picture like the Knight that kills the Gyant in a Romance’. The sight instead of a mere mortal, in fact a very ordinary man that ‘methinks … looks as like Tom or Dick as ever I saw any body in my life’ reminded him of the commonplace appearance and ‘aire of our late King’.10 Emotionally, William was more royalist than parliamentarian but this less than respectful reference just three years after Charles’s traumatic execution, to what true royalists at that time would consider a martyred king, revealed his independent mind in action. To write of the ‘aire’ or manner of the king also suggested he had seen Charles I in life. If this was so then this visit to the Isle of Wight was the probable occasion for such a meeting.

Whether he saw the king or not, the most momentous event that year for William Temple was his chance meeting with Dorothy Osborne, a coup de foudre that transformed their lives. In 1648, probably in the early summer, an unexpected and potentially inflammatory confrontation with the nervous authorities on the island propelled their attraction for each other into something deeper. Just as Dorothy and her brother Robin were on their way to embark the boat for France, Robin impulsively ran back to the inn where they had just spent the night. A hotheaded young royalist, his outrage at the imprisonment of the king, and possibly festering resentment of his father’s ill-treatment too, had been fuelled by their proximity to the castle. With the diamond from a ring he scratched into the window pane a biblical quotation in defiant protest at Governor Hammond’s actions: ‘And Hammon was hanged upon the gallows he had prepared for Mordecai.’11 The insult was not just aimed at Hammond, it implied (for everyone knew their Bible) a complete political reversal and the confounding of one’s enemies. The unwritten next sentence was: ‘Then was the King’s wrath pacified.’

As Robin made his escape and ran back to where his sister, and most likely William Temple too, was waiting he was seized by the authorities and the youthful party were taken before the governor. That summer the parliamentary forces guarding the island were particularly suspicious and quick to react, having been alerted to the fact that their royal prisoner had already attempted two abortive escapes from their custody: in this febrile atmosphere these foolhardy young people were in danger of imprisonment, if not of actually being shot.

It was not only William’s relations who seemed to be influential on the island, however, for Dorothy and Robin also had a close kinsman, Richard Osborne, living in the castle as Charles I’s gentleman-of-the-bedchamber. He was implicated in at least one of the harebrained plots for the king’s escape, and the family connection may well have added further reason for their father’s exile in St Malo. The Osbornes were becoming known as royalist troublemakers. Little wonder then that this young Osborne’s appearance before a hard-pressed governor, confronted with his personally insulting and seditious graffiti, was not treated as a youthful prank.

Robin was one year older than Dorothy but she was the quicker witted and more judicious. As her brother was charged, Dorothy confounded all by stepping forward and claiming the offence as her own. This took a certain courage given her avowed dislike of drawing attention to herself and her almost pathological fear of inviting others’ scorn. It was also a dangerous time to admit to royalist affiliation expressed in such a threatening analogy. But Dorothy may not have just been impetuously protective of her brother, she may have hoped too that natural chivalry and social prejudices would work in their favour. Men were held responsible for the politics of a family and this meant women, like children, should not be punished for political crimes, their opinions considered the responsibility of their husbands and fathers.

Perhaps it was not just the governor’s reluctance to charge a woman that saved Dorothy and her brother: the fact that her new friend happened to be Governor Hammond’s cousin might have brought some influence to bear on the case. Almost certainly William was present when the Osbornes were arrested. His sister Martha remembered his report of this incident and how impressed he was with Dorothy’s spirited action: she considered this the moment when William committed his heart. The unfolding national drama and their own sense of shared danger had inflamed their youthful spirits into a passion grand enough to withstand anything. From that point William and Dorothy chose a lengthy and difficult path that became an epic tale in itself: ‘In this Journey began an amour between Sr W T and Mrs Osborne of wch the accidents for seven years might make a History.’12

Dorothy and her brother were free to continue their journey to France, now with heightened spirits, having with ingenuity escaped punishment, even death. They were joined by William whose easy talk and dashing good looks transformed the whole expedition. On the journey to St Malo the boat either passed near Herm, or Dorothy and William made a later expedition to it. One of the smallest Channel Islands, or Les Iles de la Manche as they were still known, it was then home to deer and rabbits, its coast a haven for smugglers, pirates and seabirds. The sight there of an isolated cottage caught the romantic imaginations of both young people: a few years later Dorothy reminded William, at a time when she was longing to escape with him the constraints of their more mundane world: ‘Doe you remember Arme [Herm] and the little house there[?] shall we goe thither[?] that’s next to being out of the world[.] there wee might live like Baucis and Philemon,* grow old together in our little Cottage and for our Charrity to some shipwrakt stranger obtaine the blessing of dyeing both at the same time.’13

Ovid’s story of these two lovers had particularly affected Dorothy who admitted to William that she cried the first time she read it in the Metamorphoses. She thought this the most satisfying of Ovid’s stories and identified with ‘the perfectest Characters of a con[ten]ted marriage where Piety and Love were all there wealth’.14 Perhaps as she was reunited in St Malo with her broken and dispossessed father she was reminded of how, like him, the gods, whom Baucis and Philemon had sheltered, had first been denied help by those from whom it was most due. She and her mother too had had doors closed against them in their desperate attempts to get food and supplies through to Sir Peter and his garrison. In her sense of abandonment she might have felt like Ovid’s gods ‘mille domos clausere serae15 [a thousand homes were barred against them]’.

Already emotionally committed to Dorothy, William stayed on with her and the Osborne family for at least a month, delaying his departure on the rest of his European tour. Dorothy was to write to him later that his frankness and his good nature were his most attractive qualities: ‘twas the first thing I liked in you, and without it I should nere have lik[ed] any thing’. Good nature was thought by some to be the sign of a simple nature, she thought, ‘credulous, apt to bee abused’, but Dorothy would always rather they both erred that way than became cynical and two-faced: ‘People that have noe good Nature, and those are the person’s I have ever observed to bee fullest of tricks, little ugly plotts, and design’s, unnecessary disguises, and mean Cunnings; which are the basest quality’s in the whole worlde.’16 This honesty and plain speaking was something they both shared, a quality that was not necessarily appreciated, in a woman at least. ‘Often I have bin told,’ Dorothy wrote to William later, ‘that I had too much franchise in my humor [frankness in my disposition] and that ’twas a point of good breeding to disguise handsomly.’17 Dorothy’s excuse was that such discretion could hardly be expected from someone who had been isolated from court life since she was a child.

During this month of close company and constant conversation Dorothy and William discovered a rare compatibility: ‘his thoughts mett with hers as indeed they could not choos, since they had both but one heart,’ he added in one of his personalised romances written specially for her. It is most likely that it was William who first declared his feelings. He was of a more impetuous and immediately expressive nature: his sister described him as having ‘passions naturaly warme, & quick, but temper’d by reason & thought’.18 Dorothy anyway was horrified at the idea of a woman courting a man and objected to fictions where this was made to happen: ‘It will never enter into my head that tis possible any woman can Love where she is not first Loved.’19

Dorothy noticed that they had a similar recipe for contentment, possibly highlighted by their mutual response to the dream of living like Philemon and Baucis in their island retreat: ‘only you and I agree,’ she wrote later, ‘[contentment] tis to bee found by us in a True friend,* a moderat fortune, and a retired life’.20 This sense of destiny, made more intense by their youth (they were both just over twenty), would arm them against the pain of separation and frustration of their desires that they endured in the long years to come. The unusualness for the time of their dogged resistance to their parents’ wishes and their obstinate insistence on the pursuit of love also spoke of their own romantic temperaments and the extraordinary power of their clandestine letters to each other. These alone, through periods of extended separation and family harassment, were all they had to keep the flame alive and bolster each other’s belief in the possibility of marriage and consummation at last. ‘Read my heart,’ Dorothy wrote in one of her letters and that heartfelt quality is just what gave them such compelling force, for they carried all her intelligence, humour and longing for William in their separate exiles.

William and Dorothy united their fates against great practical, cultural and familial odds. Their falling in love with each other was not just a transformation of the heart. It involved a revolution against everything they had been bred to be, challenging the blind duty of children towards their parents, the pecuniary aspect of marriage and the inferiority of women in their relations with men.

Dorothy was intellectual, self-contained and enigmatic, her dark-eyed beauty perhaps inherited, along with her forthright character, from her Danvers grandmother, who the biographer John Evelyn claimed had Italian blood. William was even more conventionally good-looking; in Dorothy’s own words, ‘a very pritty gentleman and a modest [one]’.21 According to his sister his luxuriant dark brown hair ‘curl’d naturaly, & while that was esteem’d a beauty nobody had it in more perfection’.22 In an age of shaved heads and extravagant wigs, he wore his own hair long and unpowdered. He was tall and athletically built and overflowing with a breezy energy and enthusiasm that attracted everyone. Dorothy’s seriousness of mind would deepen his character while his own ‘great humanity & good nature, takeing pleasure in makeing others easy and happy’23 brought warmth and optimism to a woman who felt keenly the darker side of life. ‘I never apeare to bee very merry, and if I had all that I could wish for in the World I doe not thinke it would make any visible change in my humor,’24 was how she explained her naturally pensive, even sorrowful, expression.

Their stolen month of ecstatic discovery was brought to an abrupt end. Sir John Temple had learned with irritation that his son had barely travelled beyond the English shores; his irritation became alarm when he heard ‘the occasion of it’: his son’s delight in an impoverished young woman. He issued the stern parental order to depart to Paris without delay. This was an age when even grown children expected to obey their parents absolutely and in this William conformed immediately. Both he and Dorothy would continue to honour their parents’ wishes, even when they ran diametrically opposed to their own, although through evasion and covert rebellion they managed not always to comply. There were crucial material, social as well as moral imperatives for filial duty and both Temple and Osborne fathers intended to enforce them. For Dorothy and William to marry without family support meant a precipitous plunge into poverty as family money was withheld; and with the debilitating loss of social status came diminished opportunities for suitable employment. However, much as both families disliked the idea of love entering marriage negotiations and obstinately continued to frustrate this renegade plan, the subversive lovers made a private commitment to each other while in St Malo and trusted they might have a future together some day.

Looking back on their lives, William’s sister had thought his and Dorothy’s courtship was as good a love story as any fiction and that their letters should have been published as a ‘Volum’. ‘I have often wish’d the[y] might bee printed,’ she wrote, and even though she thought her brother’s writings exceptional it was Dorothy’s letters that she particularly admired: ‘I never saw any thing more extraordinary then hers.’25 This call for their publication was a radical statement at the time. It was perhaps a measure of how highly esteemed Dorothy’s letters were, even by contemporaries, that Martha could envisage personal love letters from a woman to a man, to whom she had been forbidden to write and had yet to marry, could ever properly be published when such exposure was considered unwomanly, or worse. The extreme vicissitudes of their love affair were recognised by everyone who knew them, and most acutely by Dorothy and William themselves, as making their story akin to the best fictional romances where true love was thwarted at every turn until the final satisfying embrace.

No letters survived from this first stage of their separation but both refer to this period in other contexts. In the following two to four years William re-wrote romances from the French* and amplified them for his own and Dorothy’s enjoyment. He also used the dramas to work out his own youthful thoughts and feelings on the conundrums of human experience and to distract him from his own unhappiness at being forcibly separated from the woman he loved. They were an outlet too for his frustrated desires, a proxy voice for feelings he was unable to express to her in person: ‘a vent to my passion, all I made others say was what I should have said myself to you upon the like occasion’.27 He revealed just how much she haunted him: ‘[I] shewd you a heart wch you have so wholly taken up that contentment could nere find a room in it since first you came there.’28 William told Dorothy they were meant to be read as letters from him to her.

A letter composed by William and introduced into the plot of one of these romances, The Constant Desperado, spoke directly to her alone, he declared, the more passionate the feeling, the more personally it was written for her: ‘you will find in this a letter that was meant to you though nere superscribd, and bee confident whatever in it is passionate said twas you indited [it was composed for you].’29

Embedding his messages in the overheated atmosphere of a French romance also gave William a means of communicating intense emotion and dramatic declarations without embarrassment. Despite some hyperbole necessary for the genre, his sense of loss and despair in being separated from Dorothy was real and direct and expressive of his own youth and overflowing feelings. It also gave an insight into her conversations with him before he left on his journey, when she feared most that his declarations of love were just airy confections and would disperse on the wind:

Madam

I count all that time but lost which I liv’d without knowing you … Tis impossible to tell you how often I have died since I left you, for I have done it as often as I have thought of you, and thought of you as often as I have breath’d; you thinke it strange that I am dead and yet have motion enough to write, alas (Madam) though I am dead, my passion lives, and tis that now writes to you, not I; have I not often told you that would never dye? And as often I could never outlive the losse of your sight; you at first thought them winde like other words, and they would soone blow over, but learne (Madam) a lovers heart is allwayes at his mouth when his Mistresse is neere him … for all this[,] dead as I am[,] if my hopes are not so too, and there are any of seeing you, methinks your eyes would revive mee … Let me know by your letters you remember mee, if you would not have mee dye beyond all hopes of a resurrection.30

In writing these personalised romances for Dorothy, William was also setting himself up in competition with the French writers she so much esteemed. Throughout their courtship she urged the turgid volumes upon him, begging him to read them too so that she could discuss character and motivation with him. Here he was attempting a pre-emptive strike, hoping perhaps that she would rate his work as highly as theirs, or at least see him in an enhanced light. His romances also pursued certain philosophical and moral arguments that suggest something of their youthful discussions, as well as the surge of emotion that overcame them both during their transfiguring month in St Malo.

In speaking of the hero of one of his stories, William amplified his country pursuits into allegories on life itself. Here he appears to acknowledge that his newfound love also brought danger; the greater the ecstasy the more painful the loss. In love, he was now no longer safe and self-contained and his carefree days were over:

sometimes he flies the tender partridge, others the soaring hearne [heron] and his hawkes never missing, hee concludes that fly wee high or low wee must all at length come alike to the ground; if there bee any difference that the loftier flight has the deadlier fall. sometimes with his angle hee beguiles the silly fish, and not without some pitty of theire innocence, observes how theire pleasure proves theire bane and how greedily they swallow the baite wch covers a hooke that shall teare out theire bowels, hee compares lovers to these little wittlesse creatures, and thinks them the fonder [more foolish] of the two, that with such greedy eyes stand gazing at a face, whose beguiling regards will pierce into theire hearts, and cost them theire freedome and content if they scape with theire lives.31

The face he had gazed on he described thus: ‘her eyes black as the night seem’d to presage the fate of all such as beheld them. Her browne haire curl’d in rings, but indeed they were chaines that enslav’d all hearts that were so bold as to approach them.’32 There is no doubt that he was pointedly describing Dorothy, from whom he was exiled at the time. During the six and a half years of their separation she was indeed circled by suitors bold enough to approach her. She was pressed by her father, and then more threateningly by her brother, to accept anyone with a suitable fortune, but she withstood the emotional blackmail, deprecating each suitor to William with a sharp wit and dispatching them all with unsentimental glee. But her position was parlous. For most of their courtship, Dorothy was secluded in her family’s country house, not knowing whether William would remain loyal or that either of them could continue to resist the family pressure on them to conform. At times their spirits and hope failed them. Illness, depression and threats of death made their ugly interjections. There could never be any certainty until their struggle had run its course.

Somehow, through personal tragedy, family blackmail, enforced separation, misunderstandings, ridicule and despair, Dorothy and William clung against all the odds to a sometimes faltering faith in each other and in the triumph of romantic love. For a young couple to maintain their fidelity to an ideal of a self-determined life, no matter what outrage, arguments and threats were marshalled against them, merely compounded in the eyes of the world their disrespect and folly. For Dorothy Osborne and William Temple to remain constant to each other and overcome every obstacle, from when they first met in 1648 through to their eventual, longed-for consummation at Christmas 1654, was remarkable indeed. Dorothy wrote to him in the midst of their trials: ‘can there bee a more Romance Story than ours would make if the conclusion should prove happy[?]’33 but it seemed the vainest hope.

* Lady Halkett (1623–99) was born Anne Murray, her father a tutor to Charles I and then provost of Eton College. He died when she was a baby and her remarkable mother became governess to the royal children. Anne was a highly intelligent and spirited young woman and after a wild and adventurous life as the assistant to a secret agent employed by Charles I she eventually married a widower, Sir James Halkett, at the late age of thirty-three. After the death of her husband she became a teacher herself.

* Robert Hammond (1621–54), a distinguished parliamentarian soldier and friend of Cromwell, nephew of the royalist divine Dr Henry Hammond, chaplain to the king, and cousin to William Temple. Sent by Cromwell to Ireland as a member of the Irish council responsible for reorganising the judiciary, he caught a fever and died at the age of thirty-three.

† Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria (1614–62), governor of the Spanish Netherlands and art collector. His collection is now part of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

* Ovid’s Metamorphoses, viii, 620–724. Philemon’s name connoted love and that of his wife Baucis modesty. Dorothy had identified closely with the old couple who had been wedded in their youth and lived in contented poverty, growing older and ever closer. For their simple kindness and hospitality to the gods Jupiter and Mercury, who were travelling incognito and had been denied succour at every other door, they were rewarded with a temple in place of their cottage and transformed into priests and granted their only request: that having lived so long together in close companionship they might be allowed to die together. As death approached, they both transmuted into trees, Philemon an oak and Baucis a linden tree, their trunks and branches so closely intertwined they were as one. Dorothy’s own signed copy of the 1626 edition of Sandys’s translation of Ovid is now in the Osborn collection in the Beinecke Library at Yale.

* They both used the word ‘friend’ to mean also a close family member, most notably a spouse.

* William Temple adapted his series of romances from François de Rosset’s Histoires Tragiques, a collection of nineteen versions of true stories that were collected and published in 1615 with many further editions. William’s additions and departures from the original were expressive of his more sympathetic nature and philosophical mind, as well as outlets for frustrated feeling. Most significantly, however, they were personal messages to the woman for whom he was writing.