Читать книгу New Land, New Lives - Janet Elaine Guthrie - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGretchen Yost

“We had to find out ways for ourselves how to make things go.”

Ten-year-old Greta, or Gretchen as she became known in English, emigrated with her mother and brother in 1919. From 1920 she lived in Tacoma. On her own at the age of fourteen, Gretchen worked in a cafeteria and later baked and sold pies. She shared favorite food customs with her three children, but cultivated no formal ties with her Swedish heritage.

My name was Greta Karlsson. I was born July 25, 1909, in Malmö, Sweden. Malmö was a very busy metropolis.* I remember its cleanliness and I remember the birch trees down the inner section of the roads. But no small homes; they were building apartment complexes. There would be a cement court in the middle and then all these apartments around. You went in through like a gate, actually not a gate but an opening. Inside, they would have a level up where all the little outhouses were, because there wasn’t any indoor plumbing. The courtyard was a place for the children to play. It was a fabulous place, because [at Midsummer] the big maypole would be put up and the violins and the accordions would come and everyone would dance.

That was fish country. I remember the fishermen coming in this courtyard with a cart and calling out “Limhamnssill, Limhamnssill.” Limhamn was a little fishing country [village, now suburb of Malmö] and sill of course meant fish [herring].

You came into a hallway. It was quite dark. Then it had a small kitchen where my mother always had flowers of some kind growing. I remember very vividly that she’d have nasturtiums and how bright they were in the window. Then there was one small bedroom and one a little bit larger. We ate in the kitchen. It was just very small. No indoor plumbing as far as the toilet facilities was concerned, but yet we had water. All these little outhouses were locked, so I had the key around my neck when we’d be out playing.

My mother was a widow. My father was drowned when I was six months old. He was a fireman on a ship. And so, from then on it was hard work. My mother couldn’t make enough and us children had to help. She was cleaning office buildings or whatever menial labor she could get. My brother had a job working for a fruit company where he would haul the fruit in a wooden cart; and when the fruit got ripe we were very happy, because he could bring it home if it got too ripe.

In those days there wasn’t the fear of children being on the street or in a crowd. My brother was a real promoter. He was old for his age. And he’d get this type of a job and that type of a job. He had this job selling newspapers and magazines and he involved me in it. I used to sell magazines and papers in the depot when I was five years old. My brother was five years older than myself; he’d hide behind the post to see that I didn’t get away with anything and they bought a lot from me. Of course, I wasn’t old enough to go to school and he was, so I had to stay at home in the apartment during the day by myself—which left an effect on me, because I was always afraid of being alone afterwards.

It was just a matter of survival. Everybody had to pull together. Lots of little odd jobs that we would do that would help us bring in a little bit of money. Running errands and that type of thing for people, too. During the First World War, I can remember my mother taking a blanket and going and standing in line at the commissary and laying down on the blanket. And in the morning there would be nothing left, she couldn’t bring food home. There were many beggars that would come right to the apartment. Mother always shared whatever crust we had. There were a lot of people that were going through miserable, miserable times.

I can remember vividly saving our öre, which is like your penny, so that once in a great while we could stand in line for hours and get way, way up at the top to see an opera. Or maybe saving a little bit so we could go to the bakery and get a big bun full of whipped cream. That was part of our scrimping, to be able to do things that other children had every day. I remember the royalty coming to Malmö one time and we lining up the street to see the coach go by—to see the king and queen, which was a big thing for us.

My mother was a great baker. I can remember her making coffee cakes, braiding them. Kåldolmar, it’s meat and rice wrapped in cabbage leaves. And filbunke—when we had a little extra, my mother would clabber milk, make it like soured milk; it was smooth like yogurt. And, of course, Christmas time back there. We would always have lingonberries and rice. You would have before Christmas and you would have after Christmas and you would have so many days. And, of course, herring and lutfisk.* Then they’d have this candy that was on a string, rock candy. You’d go in and buy and they’d break off a little piece of that.

I started school there but we didn’t go very long, just a very short time. Growing up the way we grew up, we had to find out ways for ourselves, how to make things go. I just picked it up. That’s why it’s a bit amusing to me today that we have to have all these classes, because I had to learn on my own.

We did get out into the country. The government would ask people who were of means to take the children into their homes for holidays. And I can remember one time going to a very wealthy family at Christmas time; it really made a big impression on me. The maid brought me a doll for Christmas. It didn’t have its head sewed on, it was tied on with a piece of cloth because the people were busy. They did this as a thing they should do, but that’s all it meant to them. They were away partying. My brother got to go out on a farm for awhile. Otherwise, our life was pretty drab.

My mother had an aunt and uncle in Porter, Indiana, that’s by Chicago. They had a big mercantile store and they had written to her and asked if she’d like to come over here and work for them. They said they would send a ticket for myself and her, and she said she would not come without my brother. So she doubled up on her job. When she had enough saved, that’s when we came to this country, 1919, in February. I was only nine.

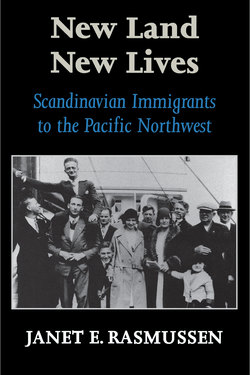

This is the passport photo before we left. My brother had borrowed somebody’s chain, it looked like he had a watch fob. This was a friend of mine’s dress. We put on the best clothes for the passport. But mother was very unhappy to go. And in that picture it shows her face was swollen from crying. I can remember her crying so. It was her life back there and we didn’t know what we were getting into. We didn’t know a word of English. We thought this country was going to be a country of Indians, cowboys, shooting—we didn’t know. My mother, the little bit of money she had, she sewed inside of her undergarments to protect.

I remember when we landed, squirming through all the grown-up people to see the Statue of Liberty. I had [bought] my first pair of shoes and they were button-up high shoes and somebody stepped on them and I spit on my shoes. I wanted them to be so shiny. I remember when we were met at the station at Porter, Indiana. It was my first car, a touring car with icicle glass [isinglass] in it. I leaned out, I wanted everybody to see me. I thought, “Are you looking at me? I’m in a car!” And I had a funny little round hat, a little tweed hat, and my long braids. I don’t think anyone realizes the excitement of a new country. Today, of course, I’m very thankful; it’s been my country.

Mother wasn’t very well and we didn’t realize how ill she really was. We were in Porter fifteen months and we came west to Portland [Oregon]. My mother married and then she became very ill. They diagnosed it as quick consumption—tuberculosis. She died then in June of 1920.

I was cut off by my mother passing away; no contact back to Sweden. I can’t speak Swedish anymore because I didn’t keep up that contact. But it’s a very dear thing to me. I remember so well. I remember those streets, and what went on there.

*Located at the southern tip of Sweden, Malmö had 83,000 inhabitants in 1910.

*Lutfisk is codfish that has been treated in a lye-like solution and then cooked. In parts of Sweden and Norway, it is a traditional Christmas dish. In addition, as noted in the interview with Torvald Opsal earlier, it is often featured at Scandinavian-American festivities.