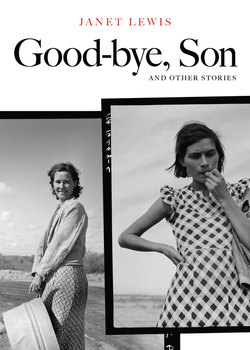

Читать книгу Good-bye, Son and Other Stories - Janet Lewis - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеRiver

IN THE SHALLOWS the boat grounded, and it began to rain again. The children lifted their faces and sniffed the dampness, and Scotty put on his rubber cap that made him look like a devil. The Dominie stepped overboard with his shoes on and took the narrow painter over his shoulder. The boat lifted, floating lightly. Edith wanted to get out and push; she took her sandals off. But the twins wouldn’t let her.

“It’s probably over your head,” said Scott.

Edith said, “Pooh.”

The boat slipped through the rushes, the round green stems bent and rose behind them unharmed in a wall. They scraped softly against the sides of the boat, making a prolonged, firm “hush.” The rain thickened, and the Dominie’s back under the yellow poncho looked very high and large.

When the rushes ended and they came to the deep place between the rushes and the shore, the Dominie stepped back into the boat, which rocked under him, sending long ripples in arcs all over the still water. The rain seemed to stop. He took an oar and paddled to the exact center of the pool, dropped the small muddy anchor, and sat down.

They baited their hooks and the Dominie set the minnow bucket under the thwart. “To keep the sun off it,” he said. The twins smiled.

Edith listened to the quiet. It was made up of little noises. There was the clicking of the reels as they all let out their lines and hunted for bottom, and reeled in a little. There was Scotty talking to his minnow, which he had dropped twice and was still working over. There was the water lipping the bottom of the boat. It was not cold, but it was very wet. Scott finally hooked his minnow, holding the little cold body carefully in his left hand and passing the point of the blue steel hook under the chin and up through the nose. The minnow did not wink or quiver, and when he dropped it overboard it gave a little flip with its tail and swam down out of sight.

“You’Ve got a bite,” said Edith.

‘Weed,” said John, reeling in.

The weed was a bright shiny green. It was twined about the hook and the minnow was about three inches above it on the line. John detached the minnow and threw it away with a wide sweep of his arm. They heard it splash, and then, almost immediately, another splash as a gull swooped for it and got it. The Dominie passed the minnow bucket without comment. The gull was a little Napoleon with bright red feet and a body the color of the cloudy sky.

The Dominie filled his pipe, tamping the tobacco with the tip of his little finger, and lighted it. When he bent his head to shield the match some water on the brim of his hat rolled off in round drops. His glasses were dry, but his brown beard and mustachios were dewed with wet.

Edith said, “There goes the Elva.”

The boys lifted their eyes from their lines and watched the small white boat steaming far down-channel, its straight prow lifted and the two decks slanting backward as if to shed the rain. The shore was near them, rushes, tag alder, and Indian plum. Now in late June the leaves were summer foliage, thick and dark. There was a long pile of pulpwood on the beach, cut during the winter and waiting for some schooner like the Our Son to take it on downstream. They knew that it was five o’clock because of the Elva.

The rain began again and settled to a quiet steady downpour. Scott began to sing.

“Shut up,” said John cheerfully, “you’ll scare the fish.”

“Sounds in the air don’t scare the fish,” said Scotty. “It’s your big feet. Not right, sir?”

“Perfectly right,” said the Dominie. Scott went on singing and the others joined. They sang, “Oh, the ocean waves may roll,” and the raindrops, hitting the water on all sides of them, sounded like dried peas thrown on leather. Edith put out her tongue and began to lick the rain from the corners of her cheeks.

The Dominie looked at his wet children and they smiled back at him. They could hardly be any wetter, he thought, but they looked healthy enough. Even the pallor of the little girl had a healthy brightness. Her hair held the water from her head except near her face and the back of her neck where the locks were pasted to the skin. The Dominie took his pipe from between his teeth to say, “Her hair hung down upon her face Like seaweed on a clam.”

They did not catch a single fish.

It was a good deal after six when they passed through the reeds again and regained the open river. The sky was a great pearly dome, reflected on the water whitely, and the shores were dark. The rain had stopped at last, the water was smooth. Edith sat in the prow because she weighed the least, where she looked over the Dominie’s back at the two boys and, beyond them, at the American shore. They were heading for Canada.

“Why didn’t they bite?” said Scott. “Wasn’t the water cold enough? I hate to be skunked.”

“Probably too early in the season,” said John. “They haven’t had time to grow up yet.”

“Oh, you,” said Scott. “We didn’t catch them all, last year.” He added, to the Dominie, “Deadhead ahead on your right, sir.”

The Dominie swerved, but the boat hit something, dully. The children saw it as it came alongside, the body of a man revolving a little, slowly, in the water. The brown, pale face was upturned, the water flowing in thin milky layers over it. The Dominie lunged and caught it by the coat. The boat tipped, and the boys leaned hard to starboard to steady it.

“It’s old Nick, all right,” said the Dominie, “turning up at last.”

He began to unfasten the stringer that was tied to the thwart on which he was sitting, working slowly with one hand, holding the body with the other. The children remembered then what they had heard of old Nick sitting on the railing of the Elva, drunk. He had fallen over backward and had gone down at once. The body had not risen. It had happened almost a week before their arrival, when the water in mid-channel must have been like ice.

The Dominie ran the point of the stringer through the coat collar, fastened it in a half hitch, and turned the body over. The coat was unbuttoned, and he buttoned it. When he had finished, the sleeves of his gray flannel shirt were wet halfway to the elbow. He passed the end of the stringer to Scott, who made it fast on his side of the boat as far astern as he could. Then he turned the boat and rowed slowly in the direction of the post office.

The boat moved forward with a gliding, jerking motion. The body, trailing behind to one side, made it slew around, and every so often Scott said to his father, “Hard on your right, sir.”

The rowlocks creaked, paused, creaked to the Dominies short, even stroke, and the burden they were towing raised the water in a ripple that splashed irregularly, sounding like the ripple caused by a stringerful of fish. John turned and looked carefully at his brother for a moment, but Scott was watching the water ahead of them. The Dominie frowned a little as he rowed, and once Edith put out her hand and touched the wet gunwale beside her, as if to reassure herself about something. The wood was cold, and she withdrew her hand quickly and sat on it, to warm it. Beside her feet were the haphazard coils of the anchor line, and the anchor, galvanized metal splashed with pale mud, the flanges upturned. A motion of the poncho had spilled a trickle of water between her bare knees, and she held them close together.

The river behind them widened almost out of sight. Ahead of them it narrowed, the islands drawing close together for the turn at the Point. They passed a channel stake, a big timber painted black with a number in white, and anchored to the bottom of the river. The weight of moving water tipped it to a forty-five-degree angle with the surface of the river, and as it hung there it revolved, first in one direction and then in the other, but the surface of the river was smooth because the water was very deep.

They went on in toward shore where the current was less strong, and then upstream again to the post office dock. The post office and the postmaster’s house stood near the shore. The hill rose abruptly behind the buildings, carrying the dark pines high above. The houses could be entered from the back at the second story by a gallery which ran out level with the hill. A flight of wooden steps came down the hill between the two houses, and from it a boardwalk ran out straight with the line of the dock. A big pile of broken gray rock made a sort of lagoon in front of the dock. It had been dumped there when the channel was being cut and dredged, and no one had ever bothered to take it away. The post office was closed, and the shades were drawn in the house next door. There was no porch to either house, only a straight shingled front with a peaked gable at the top. The wood, that was silvery in dry weather, was black now.

The Dominie hallooed, holding to the edge of the dock with his right hand. A door at the back of the post office opened, and the son of the postmaster came out, bare-headed. He was a big blond fellow. He came down the dock toward them in a half run, lurching with a sort of heavy grace. His feet, in the brown canvas shoes, made little noise, but the planks of the dock sprang slightly under his step. When he saw what they had brought, he drew his breath in between his teeth and lower lip in a whistling sound and swore softly.

He said, “Just moor the old boy to the dock, Perfessor, and I’ll take care of him—telephone the Soo and all that. Think I’d better get into my waders before I try to take him ashore, though.”

“You can keep the stringer,” the Dominie said.

The stone pile hid the dock from sight quickly as they rowed away. The Dominie asked Edith if she was cold, and she said no.

In the cabin they hurried out of their wet clothes and into dry ones. Their shoes were set in a row on the brick hearth to dry, and they all ran around barefoot. The collie puppy got in everyone’s way, his cold nose and soft warm fur touching the bare ankles. He was brown with white feet as if he had just stepped out of a pan of milk. The Dominie decided to make pancakes and the children’s mother turned the kitchen over to him. She sat by the lamp, rocking and knitting, and the Dominie shouted remarks to her from the kitchen. He was very gay and gentle, looking at the children with a sort of whimsical concern and teasing them.

In the morning the sun was out and the world glistened. Edith ran along the sand in her bathing suit. Her feet did not dent the sand, but where she stepped the pressure of her foot brought a film of water to the surface, which shone and disappeared. The sun was high and hot. The boys were already diving from the end of the government dock. The dock and the red-and-yellow warehouse were reflected upside down, almost inch for inch. Edith stood looking into the clear water, letting the ripples nibble at her toes. The Dominie sauntered along the shore, smoking, and kicking at the pale drift of wet rushes. He said gently, “Afraid of the river this morning?”

“No,” she answered, looking up in surprise. “Ought I to be?”

“No,” he said. “I think not.”