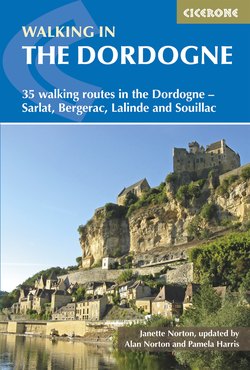

Читать книгу Walking in the Dordogne - Janette Norton - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Spring blossom near Lalinde (Walk 12): photo Richard Saynor

The Dordogne is one of the most beautiful areas of France, with at its centre the river that gave its name to the department. It is a land of great scenic variety, from rolling wooded hills and fertile valleys to barren upland plateaus and limestone cliffs riddled with caves. With its mild climate and delicious food, it has become a popular tourist destination for French and foreigners alike, and many English have made it their second home, finding it not unlike the rural England of the past: peaceful and unspoilt, with no big, bustling towns and motorways clogged with traffic. And perhaps the English have a particular affinity for this area because for several centuries it belonged to England, who fought bitterly to retain it in the Hundred Years’ War.

The Dordogne lies in south-west France, in the administrative region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, between the wild uplands of the Massif Central in the east and the flat fertile countryside of the Gironde and the Atlantic Ocean in the west. Corresponding to the former province of Périgord, the department was created in 1790 and named after its dominant geographical feature, the river. However, the French frequently use the old name of Périgord, especially in tourist literature where it is subdivided into four sections: Périgord Vert (green) in the north, Périgord Blanc (white) in the centre, Périgord Pourpre (purple) in the south-west and Périgord Noir (black) in the south-east.

Périgord Vert is, as its name implies, a green landscape of fields and woods, which lies to the south of the large towns of Angoulême and Limousin. It is traversed by countless small rivers tumbling down from the nearby Massif Central to converge on the Dronne, which winds its way southwards to join the Dordogne at the town of Libourne near the large Atlantic port of Bordeaux. Less well known than its southern counterparts, Périgord Vert forms part of the Périgord-Limousin Regional Nature Park.

Périgord Blanc, so called because of the whiteness of its chalky limestone, is also north of the Dordogne river and is home to the department’s capital, Périgueux. Founded by the Gauls in a fertile valley on the River Isle, it became a prosperous town under the Romans, who called it Vesunna after its sacred spring. It continued to grow in importance over the centuries, and the historic centre boasts a five-domed cathedral and some fine Renaissance-style buildings, as well as traces of its Roman past. Its weekly market is renowned for its truffles, foie gras and strawberries.

Périgord Pourpre lies to the south-west, and is named after the purple grapes of its famous vineyards. This is an area of rich alluvial soil, with fields of maize and cereal crops, walnut plantations and chestnut groves, with the river flowing through its heart, winding gently round the dramatic meander of the Cingle de Trémolat and passing through Lalinde to reach the town of Bergerac. A port grew up here when the only means of transporting goods to Bordeaux was by boat, and it is now a prosperous town with an attractive old quarter.

The Dordogne river at Bergerac (Walk 1)

Périgord Noir in the south-east is named after the dark colour of its evergreen oak forests, and is perhaps the best known of the four sections. The Dordogne flows more rapidly here, cutting through high cliffs, and many medieval villages and castles are to be found on its rocky banks. The Vézère river comes from the north-east to join the Dordogne at Limeuil, and it was in the overhanging rock shelters and caves below the limestone cliffs of the Vézère that early man first made his home here. The main town of Périgord Noir is Sarlat, to the north of the river. It is a joy to explore, with winding streets and honey-coloured Renaissance-style buildings.

East of Périgord Noir is the department of Lot and the upper reaches of the Dordogne river, now narrow and winding, joined at Castelnau by the smaller Bave and Cère rivers. South of the river is a limestone area of subterranean chasms known as gouffres, and arid plateaus known as causses, broken by deep gorges. The Regional Nature Park of Causses du Quercy was created in 1999, a large area used mainly for sheep farming. The gateway to the Lot is the busy little town of Souillac, which has a remarkable Romanesque abbey church. However, most visitors do not linger here, and continue to Rocamadour and the more scenic sites beyond.

All the walks in this guide are located in Périgord Pourpre, around Bergerac and Lalinde; in Périgord Noir around Sarlat; and in the Lot around Souillac. This is a richly historical area, and many of the walks start from a medieval town, or pass by a château, a Romanesque church, a large abbey, an elaborate dovecote, an old mill, a cave of prehistoric wall paintings or a Celtic hill-fort – the list is endless, and you will continually come across something of interest to make you want to stop and explore. Since the majority of walks are fairly short there is plenty of time for this, and additional background information is given in each walk description.

Walking here is a delight, and at the end of the day there is always a small café in a village square for a glass of sweet Monbazillac wine under a sun which lacks the intensity of that in southern France, followed by a dinner of regional specialities made of duck or goose in a local restaurant.

The Dordogne river

The Dordogne river west of Lalinde

The Dordogne is one of the longest rivers in France, flowing nearly 500km westwards from its source in the Massif Central to join the Garonne at Bordeaux and end in the Atlantic Ocean. There are two theories as to the origin of its name, which may come from the Celtic Durunna, meaning rapid waters, or from the two tiny streams, the Dore and the Dogne, which join high on the slopes of the Puy de Sancy to become the Dordogne.

The river flows swiftly through the mountainous area of the Auvergne to reach the lake of Bort, where it is tamed by a succession of five gigantic dams built between 1935 and 1957, together producing over 1600 million kilowatts of electricity a year. It then rushes through the Corrèze gorges to pierce the upland plateaus of the Causses du Quercy in the Lot, and by the time it reaches the department named after it, the waters are wider and calmer, although still flowing between steep cliffs. Joined at Castelnau by the Cère and the Bave, and at Limeuil by the Vézère, it continues on its journey through the countryside in a series of dramatic horseshoe meanders, the larger ones named cingles, and only straightens out when it reaches the rich alluvial plains around Bergerac. It finally joins the waters of the Garonne to become the Gironde and flow into the Atlantic. During the Hundred Years’ War, the river formed an important frontier between the English and French, who built and then fought over the castles and towns along its banks, many of them in strategic positions on high rocky cliffs, with extended views over the surrounding countryside.

From earliest times the river was the only means of transport in the region, roads being almost non-existent. Even so, for part of the year the water level was not high enough for the boats to pass, so arrival and departure times had to be carefully calculated. Wood from the chestnut and oak forests of its upper reaches in the Massif Central were floated down the river or transported on small boats called gabarots as far as Souillac, where it was loaded onto larger flat-bottomed boats called gabarres. These gabarres were 20 metres long and capable of carrying 30 tons; between 1850 and 1860, as many as 300 were built each year. Some of the wood was unloaded at Bergerac, to be used for making wine-barrels and boats, and barrels of wine were loaded for their final destination of the port of Libourne near Bordeaux, to be exported to England, Holland and the colonies. The gabarres made the return journey laden mainly with salt, but also coffee and sugar. Although the journey between Souillac and Libourne was more straightforward than that on the upper reaches before Souillac, it was still hazardous, with sections of tricky shallows and fast flowing rapids, so the boatmen had to be skilled navigators to negotiate their clumsy boats through these. In the mid-1880s a canal was built to circumvent the trickiest and most dangerous stretch of rapids near Lalinde, the Saut de la Gratusse, where special pilots were needed to guide the boats through the treacherous waters. During this period Souillac and Bergerac became important ports, and the banks of the river were studded with villages whose inhabitants gained their livelihood as boat builders, boatmen and merchants.

The coming of the railway in the 1870s brought this trade to a halt, as it was far easier and quicker to transport heavy goods by rail. The rivermen vainly fought this modern means of transport, even blowing up the railway bridges built across the river. But now, in the 21st century, it is the railways that are in decline, and gabarres are still being made to take tourists on river cruises from the small towns of la Roque-Gageac and Beynac.

Tourist gabarre at la Roque-Gageac (Walk 27)

A short history of the Dordogne

The Dordogne well merits its name as ‘the capital of pre-history’ for it was here, some 30,000 years ago, that our direct ancestors arrived. Known as Cro-Magnon man after the rock shelter near les Eyzies where their bones and stone tools were found, they made their home in caves and overhangs along the Vézère river. As time passed, they began to decorate the cave walls with realistic drawings, paintings and engravings depicting the bison, reindeer and other animals they hunted. Over the next thousands of years, as the climate got warmer and the herds moved north, these nomadic hunters became settled communities tending the soil and planting crops. They gradually learned the skill of metal-working, and their stone tools were succeeded by ones made of bronze and then iron. By 700BC Celtic tribes from the north had spread into the area, building towns and hilltop fortresses, and continually fighting among themselves. One of the most powerful of these tribes was the Petrocorii, who gave the name of Périgord to this region and built a town at the site of the modern Périgueux.

When the Romans arrived and conquered the whole of Gaul, they brought with them law and order, building new towns and roads, and planting the first vineyards. In AD16 Emperor Augustus established the province of Aquitania which extended over most of south-western France, from Poitiers to the Pyrenees. Under the ‘Pax Romana’ there was peace for three centuries and the region flourished, but it was not to last.

Romanesque church at St-Geniès (Walk 22)

Roman dominance crumbled in the fifth century as Germanic tribes pushed into Gaul, first the Visigoths and then the Franks, who gave their name to modern France. Christianity now began to spread throughout the region, and many abbeys and churches were founded. Aquitaine became increasingly powerful, first a duchy and then, for a short time under Charlemagne, an independent kingdom. Territory within the kingdom was awarded to loyal followers, and Périgord became a province, ruled by a count. When the Vikings began to raid ever further inland in the ninth century, provincial governors were given increasing power and Périgord was divided into four baronies, ruled by powerful families with fortified castles, who gave only nominal allegiance to the king of France.

By the 12th century the Duchy of Aquitaine owned a vast territory stretching from the Loire to the Pyrenees, with a court at Poitiers that was renowned for sophistication and the code of courtly love. This is where the beautiful Eleanor of Aquitaine grew up, surrounded by troubadours and poets, and as her father’s only child, she inherited the Duchy on his death in 1137. After divorcing her first husband, King Louis of France, she married Henry Plantagenet, Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy, so that when he became King Henry II of England in 1154, the whole of Aquitaine was brought under English rule. Now the English king held sway over as much of France as the French king himself, which caused frequent discontent between the two countries. The Dordogne river formed the frontier between the French and English lands, and hundreds of castles were built in the run-up to the Hundred Years’ War, many on rocky heights commanding strategic positions on the river.

As the Bordeaux wine trade flourished, towns such as Périgueux, Bergerac and Sarlat grew in importance. In addition, between 1250 and 1350 dozens of new towns were built, in order to further promote trade and commerce. These were known as bastides, from the Occitan word bastida, meaning a group of buildings. Some were founded by the French, others by the English, who thus ensured control over their inhabitants, two of the most prolific bastide founders being Alphonse de Poitiers for the French crown, and King Edward I of England. Anyone from the surrounding countryside who was prepared to build and defend the town was allocated two plots of land inside the walls, one for a house and the other for cultivation, and in addition was given exemption from certain taxes. The bastides were all laid out on the same plan, in a square or rectangle, with four main streets running at right angles between the gates, crossed and paralleled by smaller ones in a grid pattern. The streets converged in the centre on an arcaded main square with a covered market hall, the centre of commerce and activity, with a church often off to the side.

Covered market hall at Montclard (Walk 9)

The bastide towns were not originally fortified, and it was only when the conflict between the French and English intensified that they became a means of securing the land along the frontier. In 1337, when the French king confiscated all land held by the English crown, the Hundred Years’ War began, and Périgord was fought over bitterly in a series of battles. Towns and castles continually changed hands as first one side then the other gained the upper hand until finally, in 1451, Bordeaux fell into French hands and the English were decisively beaten two years later at the Battle of Castillon on the Dordogne river. Périgord became a possession of the French crown, and England lost all its lands in France, except for Calais and the Channel Isles.

The region was left impoverished and depopulated, plague and famine causing as many deaths as the war. Further disruption broke out in the Wars of Religion in the 1500s as the new Protestant thinking attracted many in the area, especially in Bergerac. Catholics rose up in protest, and bitter battles ensued between the different towns for religious dominance, Périgueux and Sarlat remaining staunchly Catholic. This discord continued for almost 30 years until the Edict of Nantes in 1598 gave Protestants the same freedom to worship and hold office as Catholics. However, this was revoked in 1685, causing many Protestant Huguenots to flee the country.

Despite major reforms instigated by Louis XIV, more outbreaks of plague and poor harvests resulted in unrest among the poorer inhabitants, while the merchant classes began to benefit from an increase in trade with the newly established colonies in North America and India. The aristocracy still controlled much of the land, and many now renovated their châteaux in the Italianate style of the Renaissance, for there was no longer a need for heavy fortifications. Despite this inequality, the French Revolution did not have such a dramatic effect in the south-west as it did on places closer to Paris. Although many châteaux and churches were plundered, the aristocracy were often able to flee or hide without being captured, some even returning years later to buy back their family homes. But with it the Revolution brought administrative changes throughout France, and in 1790 the old system of provinces was changed to that of départements (departments) with new names, the province of Périgord thus becoming the department of the Dordogne.

Renaissance façade of the Maison de la Boétie, Sarlat

While other parts of France experienced economic growth with the coming of the industrial revolution in the following century, the Dordogne remained a backwater, with no coal or mineral resources to exploit. Only Bordeaux and the towns along the river continued to prosper, the large gabarres transporting a variety of goods to the coast and onwards to Western Europe and the colonies. The opening of the Canal latéral linking the Garonne with the Canal du Midi in 1852 meant that boats could get from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, although the river was used less and less for transporting goods once the railways arrived.

Rural areas became increasingly poor, and the farmers were badly hit in the 1870s when the deadly phylloxera beetle wiped out many of the extensive vineyards around Bergerac. Although some were gradually re-established, many farmers turned to tobacco-growing or sheep-rearing. But it was World War I that changed the rhythm of rural life irrevocably as thousands of young men left to perish in the north of France. This exodus continued during the Depression of the 1930s, and the population was further depleted by World War II. When the Germans occupied the whole of France and the Resistance Movement was formed, the isolated areas of the Dordogne afforded safe bases for its fighters, although there were savage reprisals, as everywhere in France, with many villages destroyed and their inhabitants killed.

Although agricultural production, especially of wine, tobacco and walnuts, continued to be important in the years following the war, more and more small farmers left the area, and buildings fell into disrepair. But this was not to last, for in the 1960s André Malraux, minister of culture, introduced an act to preserve historic monuments. He knew the Dordogne well, and chose Sarlat as the first town to benefit from this. More than 50 of the town’s buildings were carefully restored, followed by those in other towns and villages. At the same time the many châteaux and prehistoric sites were gradually opened to the public, and the first tourists began to arrive.

And this is when the British rediscovered the Dordogne, attracted by its mild climate and beautiful countryside, and by the slow pace of life. They bought up crumbling farms, manors and mills to renovate, seeing the area as an idyllic – and inexpensive – place to retire to, or for a second home to visit on extended holidays. The Dutch and the French themselves soon followed, and by the end of the century tourism had become a major industry.

People now flock in to wander round the unspoilt villages, visit the historic sites and taste the delicious regional specialities – and also, it is to be hoped, to explore the surrounding countryside on foot.

Busy main square at Sarlat

Plants and flowers

The Dordogne, with its mild climate and gentle rainfall, is an area where almost everything grows, and there is a richness of vegetation that you do not see with the dry hot summers further south.

In such a large area it is not surprising that there is considerable diversity in the vegetation. North of the river there is extended woodland which is mainly deciduous, with chestnuts, oaks, beech and hawthorn, the most striking being the false acacia with its hanging clusters of creamy flowers. Around Sarlat and Souillac you will find plantations of walnuts and oak trees, with truffles growing at their roots. Further south, on the limestone causse, are plants more usually associated with a Mediterranean climate, where you will find evergreen holm oak, juniper, broom and dwarf conifers.

A variety of cereal crops are cultivated, and around Sarlat you will still come across a few fields of tobacco and the long wooden barns where the leaves were hung to dry. This was once the largest tobacco producing area in France, although very little has been grown since 2013 when farmers stopped receiving subsidies for growing it. And of course there are the famous vineyards around Bergerac, where the countryside is flatter and the gentle slopes are covered in vineyards as far as the eye can see.

In addition to the variety of trees and crops, the region hosts an abundance of flowers. In springtime you will find primroses, violets, periwinkles and wood anemones, as well as early flowering bulbs such as snowdrops, wild daffodils, small yellow tulips and white Star of Bethlehem. Later in summer the woods are full of tall white asphodel lilies, and the open fields carpeted with ox-eye daisies, purple sage and aquilegias. The banks of rivers and streams are bright with yellow irises and marsh marigolds, with delicate fritillaries, water avens and a variety of tall rushes. On the rocky cliffs above the river bloom creeping plants such as saxifrage and stonecrop, and in the limestone areas of the warmer south you will find lavender, thyme and rosemary. The flowers continue into autumn, when you will frequently come across carpets of tiny pink cyclamen in the woods, and autumn squill in open areas.

The most exciting aspect of this area for any flower-lover in spring and early summer is the multitude of wild orchids in the fields and woods, not just the odd specimen but large clusters of them. Some of the most impressive are the tall lizard orchids and the lovely dark lady orchids. Many grow on grassy verges, where you will frequently see early purple, pyramidal, white butterfly and fragrant orchids, whereas red and white helleborines thrive in shady woodland. Other less common varieties are the purple loose-flowered orchids, the curious tongue orchids and the ophrys varieties of bee orchid.

Clockwise from left: Lady orchid, Wild tulips, Pyramidal orchid, autumn flowering Cyclamen, Star of Bethlehem.

Suggested books:

A Naturalist’s Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain and Northern Europe, by A Cleave and P Sterry (John Beaufoy Publishing)

Field Guide to Orchids of Britain and Europe, by Karl Peter Buttler (Crowood Press)

Wild Flowers of the Mediterranean, by David Burnie (Dorling Kindersley Eyewitness Handbook)

Wildlife

The Dordogne has a history of hunting dating back to medieval times, when knights galloped out of their castles to shoot deer and wild boar, which were plentiful in the vast forests. Over the centuries the wildlife was decimated, but fortunately the recent ecology movement has had a positive result. Although hunting continues, and you will frequently come across tall hunting platforms in the woods for spotting game, there is now a defined hunting season, for both animals and birds.

A hunting platform in the woods near Monestier (Walk 4)

Wild boar still live in the woods, and red and roe deer in more open areas. The red squirrel, so rare in England, is frequently seen here, and you may be lucky enough to glimpse an elusive civet cat, pine or stone martin. Foxes, badgers, rabbits, voles, weasels and stoats are more common, and one rodent that is slowly gaining ground in the lakes and rivers is the coypu, a big furry creature with a long tail, rather like a beaver, originally introduced from South America. Unfortunately, their increasing numbers are destroying the riverbanks, the natural habitat of otters and water voles, and so measures are now being taken to eliminate them.

The Dordogne river used to be alive with trout, salmon, eels, pike, bream and the rarer turtle, but now, due to repeated over-fishing, sewage and insecticide, numbers have diminished. Recently steps have been taken to remedy this, and hopefully numbers will increase again. The rivers and streams are also the home of water birds, and wild ducks, coots and moorhens nest in the reeds and marshes. You will often see herons watching for fish, standing on one leg in the shallows, and if you are lucky, you might catch the blue flash of a kingfisher as it skims over the water.

Birds are everywhere, even in the vineyards where the red-legged partridge has made its home. In the woods and fields are pheasants, woodpeckers, thrushes, robins, nuthatch, blackbirds, coal tits and other common species, as well as woodcock and nightingales. Above the rocky cliffs of the Dordogne, cruising the thermals, are buzzards, black kites and peregrine falcons, the latter re-established only in the 1980s. The cliffs are riddled with the nests of colonies of swallows, swifts and sand martins, especially along the Vézère river, and the dank, dark caves, once the home of primitive man, now harbour thousands of bats.

A flamboyant hoopoe: photo Tristan Lafranchis

But the most eye-catching bird to be seen in the Dordogne, especially in the south, is the flamboyant hoopoe, which flies in at the end of April after wintering in Africa. His long curved beak, pink chest and pied wings are offset by a huge crest which opens up on landing to make him look like an Indian chief – a sight worth seeing!

Suggested books:

RSPB: Birds of Britain and Europe (Dorling Kindersley Pocket Guide)

Wild Animals of Britain and Europe (Collins Nature Guide)

How to get there

By car

Many of the walks in this book cannot be reached without a car. If you come by train or air, all the main car hire firms operate from stations and airports, and information about rental can be obtained before you leave.

If you bring your own car, Cherbourg, St-Malo and Caen are convenient ports to drive from, all served from Portsmouth and Poole by Brittany Ferries (www.brittanyferries.co.uk). For detailed travel itineraries and route planners, see www.theaa.com, www.rp.rac.co.uk, and www.viamichelin.com.

By air

With the increase of budget airlines, flying and then hiring a car can be a more convenient way to travel. There are direct flights from several UK airports to Bergerac with Ryanair (www.ryanair.com), Flybe (www.flybe.com) and Jet2 (www.jet2.com); to Brive-la-Gaillarde, near Souillac, with Ryanair and Cityjet (www.cityjet.com); and to Bordeaux with British Airways (www.britishairways.com) and Easyjet (www.easyjet.co.uk). From Bordeaux it is relatively easy to get a train to Bergerac or Sarlat.

By rail

If you contact the English office of the French Railways at RailEurope (www.raileurope.co.uk), they will send an informative brochure outlining the different ways to get to France by rail, including timetables, cost, car hire and so on.

There are frequent high-speed trains with Eurostar from London Waterloo to Lille, where you can catch a TGV to Bordeaux (total journey time, nine hours) or to Libourne, where you can change to a direct train for Bergerac. For further information, including online booking, timetables, destinations and costs, contact www.eurostar.com. Another useful website for European train travel is www.seat61.com (just click on France).

When to go

The weather in the Dordogne is pleasant for much of the year, with mild humid winters and long hot summers, and walks can be done at any season. It is very unusual to get snow in the Dordogne, although hard frosts are not unknown, such as the one in 1956 which killed off many of the vines. When the sun does shine in the winter months it is often possible to sit outside at midday, although the downside is that many hotels and restaurants tend to be shut, and tourist sites have limited opening hours until Easter. Spring can be changeable, in some years with glorious sunshine and others being cold and wet, but temperatures begin to increase in May and June, and there is less rain. More restaurants and campsites open up and there are often spectacular displays of flowers. These are two of the best months for walking, before the really hot weather sets in and the swarms of holiday makers begin to arrive. July and August are months to avoid, for they can be uncomfortably hot for walking, with violent thunderstorms often building up after a day of intense heat, as well as being the months when the French take their holidays, flocking southwards en masse and crowding the roads, restaurants, hotels and campsites, as well as the picturesque old towns and villages. It is much more pleasant to wait for September and October, when the crowds have gone and the sun is less intense, although often more reliable. This is a time to enjoy the bright autumn foliage, the vendange (grape picking) and the colourful markets with their abundance of harvest produce. However, with global warming the climate has become so capricious that one never knows what to expect at any time of year.

Accommodation

The Dordogne is a major tourist destination so there is plenty of accommodation to choose from, ranging from four-star hotels to campsites. If you plan to visit in the summer months or at holiday periods, it is advisable to book in advance. The local tourist offices will often provide a list of available accommodation and help you to book. See Appendix B for a list of websites.

Hotels

The larger towns such as Bergerac and Sarlat have numerous hotels of all categories to choose from, whereas smaller towns and villages will have just a few. A reliable chain of hotels offering comfortable accommodation at reasonable prices is Logis de France, which has several hotels in the Dordogne (www.logishotels.com).

Gîtes and chambres d’hôtes

There is also plenty of self-catering accommodation to rent in gîtes (www.gites-de-france.com), and the same website gives information on chambres d’hôtes, the French equivalent of bed and breakfast.

Camping

Campsites are graded from one to five stars and range from those offering a shop, hot showers and swimming pool to sites with basic washing facilities. A list of those in the Dordogne is available at www.campingfrance.com or www.eurocampings.co.uk.

Food and drink

One cannot write any sort of book about the Dordogne without mentioning the food, and there is nothing more delightful than sitting down to a menu de terroir (menu of local specialities) in a village restaurant after a long day’s walk, when you feel justified in being really hungry!

The Dordogne is generally referred to as Périgord when it comes to food, and is well known as the home of goose and duck, truffles and mushrooms, nuts and fruits – all accompanied by a good wine from the Bergerac vineyards.

A traditional meal often starts with the renowned foie gras, a smooth, rich paté made from the enlarged livers of goose or duck after they have been force-fed, best eaten with slivers of toast. Another regional entrée is salade du gesiers, preserved duck gizzards served warm on crisp lettuce, or tourin blanchi, a soup made from goose fat, garlic and eggs.

For the main course confit often appears, where the meat of the duck is preserved and then cooked in its own thick fat and often served with pommes sarladaise, consisting of thickly sliced potatoes fried in goose fat and garlic. Magret de canard (grilled duck breasts) is another speciality often on the menu. You will also find duck and goose served up in sausages or cassoulet (a sort of meat stew with haricot beans). In fact, the fat of ducks and geese is used for cooking just about everything, and gives every dish a delicious taste.

Geese ready to be fattened

Alternatives to duck or goose are local lamb, raised on the nearby causses in the Quercy; pork, which is often stuffed with garlic, prunes and truffles; game such as rabbit, hare or wood pigeon (pigeonneau), served in a variety of ways; or beef from nearby Limousin.

Freshwater fish often appears on the menus around Bergerac and along the river, where trout, pike and perch are fished, and you will come across eels and lampreys poached in wine. Nearer to Bordeaux a wide range of fresh sea fish from the Atlantic is available.

Truffles appear in many menus, sometimes in foie gras, or in an omelette or a sauce, and in autumn there are other types of delicious mushrooms, such as morilles, chanterelles, girolles and bolets to add flavour to the meals.

The only local cheese readily available is a goat’s cheese called cabécou which comes from the Rocamadour region. In contrast, the desserts are delicious, consisting either of fresh fruit or fruit tarts, one speciality being clafoutis, where the fruit is cooked in a batter-like cake mixture. The juiciest strawberries in the whole of France are said to come from the Dordogne, and cherry, peach and plum orchards abound, especially south of Bergerac. Walnut cakes and tarts are also popular, and nut liqueur is much appreciated.

The vineyards of Bergerac produce both red and white wines which are generally better value than those of the more prestigious Bordeaux nearby. It is worth trying the sweet Monbazillac white wine, which is often served with foie gras, and the less sweet Saussignac white. The red wines are mostly sold as Bergerac or Côtes du Bergerac, and another strong red is Pécharmant. When eating out it is a good idea to order the local house wine (vin de table), which is usually served in a jug.

Regional food and wine can always be found in the many local markets which are held once or twice a week and are great fun to wander around. In addition, there are special foires or food festivals at different times of the year, and some of those worth seeking out are at Sarlat, which has a Truffle Festival in January and a Goose Fair in March; Rocamadour, which has a Cheese Festival at Whitsun; and Beaulieu-sur-Dordogne, which has a Strawberry Festival in May. Weekly market days are listed in Appendix B.

Colourful stalls at Sarlat market

What to take

The Dordogne does not suffer from extreme ranges of temperature, although in general summers are hotter than those in the UK.

The best solution is to dress in light layers and, even if the weather looks good, take a breathable windproof jacket. Lightweight, quick-drying trousers are the most comfortable for walking – those that zip down into shorts are very practical, as even on hot days you may need long trousers to avoid getting scratched by undergrowth and prickly bushes. When the sun shines the rays are intense, so sun protection is important, as is a sun hat and sunglasses.

Walking in the Dordogne is not comparable to trekking in more rugged country, and many of the walks in this guide could be done in a good pair of training shoes. However, it is preferable and more comfortable to have a lightweight pair of boots with ankle support and soles with a good tread. Proper walking socks can also make an enormous difference to foot comfort. Most hikers now use trekking poles which help with balance, especially if you are tired. The lightest available are made of carbon fibre, and lever-lock adjustments are the easiest to use.

As none of the walks described is long, a light-weight rucksack is quite adequate. It is wise to carry a whistle and a good quality compass, and a mobile phone can be life-saving if you have an accident, although it may not work in certain areas.

A GPS is useful in bad weather or if you get lost, and many GPS units now incorporate a compass and an altimeter, based on barometric pressure and/or satellite trigonometry. There has been no let-up in the evolution of GPS technology over the past 20 years, with increased power of sophisticated hand-held units, including custom maps for downloading, and access to more satellites (including Russian ones). It is worth checking the market carefully before purchasing a GPS unit, putting the accent on good signal reception and battery life, good screen visibility in bright light, easy operation, robust and not too large and heavy. There is also a learning curve, but the effort is well-rewarded and Pete Hawkin’s Cicerone guide Navigating with a GPS gives a useful introduction.

Manufacturers’ maps for GPS download are usually very expensive, and the French IGN 1:25,000 products are no exception. However, there are open software products that are surprising effective and versatile, with special mention for openmtbmap.org (‘mtb’ covers mountain biking and hiking).

EQUIPMENT LIST

The following is a suggested list for your rucksack on a day walk:

the route description from this walking guide

the IGN 1:25.000 map recommended in the walk information box

lightweight waterproof anorak

cape or poncho that goes over everything including your rucksack (useful in the rain and for sitting on)

lightweight fleece or sweater

spare socks

sun hat, sunglasses, high-factor sun cream and lip salve

basic first-aid kit, including insect repellent and moleskins for blisters

picnic and snacks (sweets, chocolates, high energy bars, dried fruit and nuts)

water bottle – it is essential to take lots of water if the weather is hot; do not drink from streams or dubious village fountains

mobile phone, whistle, penknife and compass

optional extras: GPS, camera, binoculars and reference books (for flowers or birds)

Waymarking

The walks in the Dordogne area are well signed, but it is a region criss-crossed with paths and narrow roads, and one walk can sometimes cross another, marked in the same way. It is best to follow the route description carefully as when there is danger of taking the wrong turning, this is indicated.

Most of the walks have new wooden signposts clearly showing the various destinations and distances, with a yellow plastic top and a yellow arrow indicating the direction to take. If you are on a ‘boucle’ (circular walk), named by the local tourist office, the signpost will indicate this, together with the remaining distance at each successive signpost. In the Dordogne department (although not in the Lot), the route between signposts is often waymarked by short wooden posts with a yellow plastic top and an arrow showing a right or left turn, or a cross to show the wrong way. You might also come across a yellow plastic marker stuck to a wall or tree, or an old yellow paint splash, especially on walks in the Lot. The colour yellow is used for a circular walk, and green for a liaison (connecting) path. On two walks south of the river (Walk 6 and Walk 29) you will see an extra sign on the posts, consisting of a stylised yellow scallop shell on a blue square, indicating that this is part of the pilgrimage route of St-Jacques to Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

A post with scallop shell for the route of St-Jacques (Walk 6)

Quite a number of walks in the Dordogne are partly along sections of long-distance Grande Randonnée (GR) footpaths, which are marked by red and white horizontal stripes on posts, rocks or trees, as well as on signposts, with a red and white cross to indicate the wrong direction. In this guide you will mostly come across the GR6, which runs through the centre of the Dordogne from just east of Bordeaux, ending after 1100km near Barcelonnette in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. A few walks are partly along the GR64, which runs for 90km from les Eyzies to Rocamadour, and you will come across small sections of other GRs.

In addition to the GR footpaths, you will come across a few Grande Randonnée de Pays (GRP or GR de Pays) footpaths which are long circuits, marked by red and yellow horizontal stripes. Where the route for a walk is on a GR or a GRP footpath, this is clearly indicated in both the text and on the accompanying sketch map.

At the start of many walks the local tourist offices have erected large information boards, which are mentioned in the text of individual walks. These show a map of walks in the area and information on anything of historical or general interest. They are often in English as well as French, and it is worth taking the time to read them before setting off.

Typical signpost

Maps

A good map that gives an overall picture of the Dordogne and Lot is the Michelin Carte Routière et Touristique 1:150,000 Périgord Quercy.

Each walk in this guide is accompanied by a sketch map with coloured contours, showing key places and numbered waypoints that are highlighted in the route description. To cope with the high density of information and the different walk lengths, we have used four scales: 1:25,000, 1:33,000, 1:40,000 and 1:50,000. For additional features and detailed navigation, the relevant 1:25,000 IGN paper map is specified in the information box at the beginning of each walk. Unfortunately, only a few of the IGN maps for the Dordogne are in the Top 25 Carte de Randonnée series, which often show the walking paths explicitly; most are in the Série Bleue series, which do not show the walking routes so clearly.

A complete list of IGN maps can be found in Appendix B, together with details of where to buy or order them in the UK. Otherwise, it is easy to buy them in the region and they are sometimes cheaper in local supermarkets.

For pre-walk planning and post-analysis, all the 1:25,000 and 1:100,000 IGN maps for the whole of France are available on the internet for a very small annual subscription from www.sitytrail.com. This is the best way to be sure you have the latest editions, and is accompanied by a powerful set of tools to choose the magnification, print selected areas, superimpose recorded GPS trails and record your favourite routes online.

GPX files for all the routes described in the guide are available as free downloads to purchasers of the book at www.cicerone.co.uk/843/GPX.

GUIDELINES TO WALKING IN THE DORDOGNE

Read the walk description against a map before you go to ensure that the walk is within the capacity of all members of your party.

Give yourself plenty of time by setting off early. If a walk has a timing of five hours, allow at least one hour extra for breaks and a lunch stop.

Although the Dordogne is not usually as hot as the south of France, in summer you will need to take plenty of water and sunscreen.

It is advisable not to deviate from the marked path – if there is a shortcut it is usually shown on the map.

If you are walking alone, always tell someone where you are going.

Do not pass any barrier indicating ‘Propriété Privée’ unless the walk description indicates that this is permitted.

Even if the day looks hot and fine, take waterproof clothing as the weather can be changeable.

Remember to walk on the left-hand side of the road in order to face oncoming traffic.

Shut all gates and barriers that you go through.

Do not light matches or make a fire, especially when it has been dry.

Do not pick the wild flowers but leave them for others to enjoy.

Take your litter home with you.

Using this guide

The 35 walks in this guidebook are grouped into four sections, around the towns of Bergerac, Lalinde, Sarlat and Souillac. Each section starts with an introduction to the area covered in the walks that follow, with a few towns and villages mentioned as convenient places to stay. At the beginning of the route description for each walk there is a box giving a range of useful information: the start and finish of the walk; distance; total ascent and maximum altitude; grading and an approximation of time (see further below); the relevant IGN maps; access information to reach the start point; and signposting encountered on the walk. This information is also summarised in a route summary table in Appendix A. Throughout the route descriptions place names and features that are shown on the map are highlighted in bold.

The observations at the start of each walk give additional background information about the town or village the walk is starting from, and about any points of interest seen on the way, which might include a château or church, a prehistoric cave or Celtic hill-fort, a museum or garden, or even a boat ride.

Walk grading

All walks are within the capacity of the average walker, and are on well-marked paths or quiet roads. They are graded easy or medium, and since the Dordogne is a land of rolling woodland and shallow valleys, there are no long, steep climbs or abrupt descents. Easy walks can generally be done in a half day, and are less than 10km in distance, most with a total ascent of less than 200m. Medium walks take longer, and can be up to 18km in distance, with a total ascent of up to 500m.

The total ascent is the sum of the height gains for all the uphill stretches, by definition equal to the total descent for a circular walk. The total ascent and the maximum altitude have been extracted from the recorded GPS trails, after removing off-route wanders and smoothing GPS hiccups when too few satellites are available. GPS altitudes are accurate to about 10 metres at best, becoming tens of metres or worse in gorges or near cliffs.

Timings

The timings in this book are just an indication for a reasonably fit walker, and are mostly consistent with the times given on the local signposts. You can expect to walk between 3.5 and 4km per hour on the flat, but on a hot day the heat may slow you down, especially on a long walk; from bitter experience we also know the time can increase significantly with age!

The timings do not include pauses for picnics, rests, taking photos or looking at flowers, and it is important to leave an hour or so extra for this so as to enjoy your day.

More importantly for walks in the Dordogne, the timings do not include exploring the various places of interest passed on the walk, and you should leave plenty of time if you intend to wander around the town or village at the start of the walk, or to visit the château, prehistoric cave, museum or gardens mentioned. Sometimes this can be even more time-consuming than the walk itself, and you will find that even a short walk might take you best part of a day!