Читать книгу Becky Chan - Jared Mitchell - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THREE

ОглавлениеThe following morning, I took the ferry from North Point to Kowloon City. Down on the water the salt and morning mist smelled fresh after the all-night stink of Hong Kong Island. I sat on the lower deck and stared without purpose at the airport runway, which jutted into Kowloon Bay. It was only a few hundred feet from the ferry’s route and I dumbly watched a Thai Airways Caravelle thunder down the runway and climb out. A few weeks before, an inbound Caravelle had fallen short of the runway during a typhoon, resulting in many deaths. This morning, the sun was still low and a fresh South China Sea breeze was funnelling in through Lye Mun, and for the only time in twenty-four hours I felt cool and clean. The day would be scorching hot again.

At the Hongkong and Yaumati Ferry wharf in Kowloon City I walked down the stone steps to the bus bays. I was to cover an expected leftist demonstration outside a plastics factory. Feng Hsiao-foon had forbidden me to telephone Ah-niu, Becky’s maid, at their home. He didn’t know that I already had. Like a schoolboy, my instinct was to disregard him. In fact, I intended to visit Ah-niu in secret. At the bus plaza, three forlorn-looking palm trees invigilated over the daily ebb and flow of passengers. Young factory women, Ting Ying’s Transistor Girls, stood in corrals made out of welded grey steel pipes, waiting for buses. When a Kowloon Motor Bus No. 11B swung around a curve to the bus bay, its driver trying to keep to an impossibly tight schedule, the huge double-decker leaned over precariously toward the Transistor Girls like a great red and cream-coloured slab about to entomb them. While the women pushed and shoved each other to get aboard, the driver clambered out a little door on the side of his cab with a garden watering can to top up his radiator.

I boarded my bus and rode in the upper saloon through the squalor of Kowloon City to Kowloon Tong. Crowded into the heaving bus, I read that mornings edition of the paper. On the front page was a story about a mob of Maoists paying teenagers to throw stones at passing Kowloon Motor buses. Adjacent to that story, and this was so typical of the schizophrenia of the China Telegraph in the summer of 1967, was an overly enthusiastic item headlined “Stars Have a Ball at New Kowloon Bowling Complex.” Hong Kong didn’t have a reliable supply of drinking water, people slept in the streets and Maoists were pelting buses, but we had modern bowling lanes. The story ran with a photo of young Josephine Siu Fong-fong firing a bowling ball down an alley in the new Star Bowl.

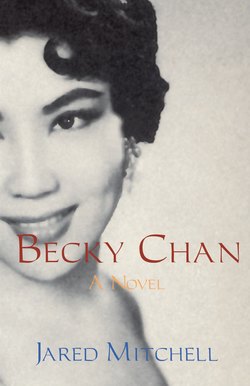

Hong Kong’s Chinese movie business was regular news and avidly covered by the China Telegraph. The paper was losing money, and management believed we had to appeal to Chinese who read English as well as lower-class Europeans and British forces personnel who were not served by the South China Morning Post. The Post was so stodgy and tame everyone called it the “Government Gazette.” The China Telegraph sought to reach people in the British forces in Hong Kong, low-ranked colonials and, most of all, educated and English-reading Chinese. So we followed Chinese entertainment closely.

Movie actresses, including Becky Chan, were constantly presiding over charity events, inaugural airline services and bank-branch ribbon cuttings. Siu Fong-fong was much younger than Becky and enormously popular with teenaged Hong Kong girls who identified with her high spirits, groovy Western clothes and a consuming preoccupation with romance, all of which were unobtainable for real-world Hong Kong girls. Even though Fong-fong starred in low-class Cantonese-dialect pictures and Becky performed almost exclusively in prestige Mandarin pictures, the younger actress was stealing the public’s attention from her.

The bus rolled up Prince Edward Road and the neighbourhood changed as the ground got higher. The filthy tenements that hunkered around the airport under the most appalling noise of screaming passenger jets gave way to tidier flat blocks. Servants worked in the car parks, wiping down Cortinas or Impalas with long dusters made of brown rooster feathers. The bus turned onto Waterloo Road, a wide thoroughfare lined with expensive low flat blocks and numerous houses. Despite the heavy traffic feeding into the newly opened Lion Rock Tunnel at the north end of town, Waterloo Road and its side streets was the best place to live in Kowloon. Long before the British allowed Chinese to live on the upper levels of the Peak on Hong Kong Island, affluent Orientals and middle-class Europeans were living in Kowloon Tong, side by side. Feng Hsiao-foon had lived here since coming down from Shanghai in 1950. He and Becky owned a smart flat-roofed house, small by Western standards of luxury, but immensely roomy for Hong Kong.

I alighted at Suffolk Road, a quiet little side street away from the groan and rattle of green-and-red delivery vans on Waterloo Road. The Feng home had a little tiled courtyard with a ficus tree surrounded by a circular stone bench, a shady place for a poet’s contemplation, but to which no poet ever came. I pressed a black intercom button. The button and the metal speaker panel were encrusted with rust from the salt air. A woman’s voice squawked out of the speaker. “Wei?” I announced myself to Ah-niu, the amah, and she buzzed me in.

The courtyard was a bit of rockery Feng had contrived, an ersatz little echo of the great Soochow-style gardens. Grotesque twisted-looking concrete rocks surrounded a little pool filled with koi fish. The courtyard came alive for a moment. An annoying little dog ran forth from under the cool of the stone bench, making a huge, snarling, slobbering show as defender of the household. Feng had named her Chung Hsiang, after the Peking opera Chung Hsiang Upsets the Classroom. She barked and snarled and almost choked on her own tongue. I hated that dog so much. I wanted to take the belt out of my trousers, chase her around the courtyard and flog it, but, clever me, I knew that Ah-niu probably wouldn’t let me in afterward. Anyway, exhausted and bankrupted by her brief performance, Chung Hsiang gave up the defence, retreated under the bench and collapsed in a ball of hair.

I looked at the house. Ah-niu was standing in a window on the ground floor and she had visible misgivings. It was rare that I was allowed to visit their house. Like many people in Hong Kong, Feng preferred not to entertain at home, but chose less private, less revealing banquet rooms in Chinese restaurants and private clubs. Admittance to Feng’s home when he was not there was normally unthinkable so it was testimony to Ah-niu’s worry about Becky. I wouldn’t have put Ah-niu at risk of Feng’s anger unless I felt it were important.

Ah-niu opened the big wooden front door. Above it was a stone tablet sunk into the wall. Carved and painted in gold were the characters for “Bricks and Mortar of the Nation, ”meaning the family home. On a small sconce beside the door was a brass plaque, also tarnished by salt air, that bore the name of Master Tsang. He had been a great opera performer who had introduced that art to South China in the Eighteenth Century. Now he was a kind of deity. Cantonese opera performers and, by extension movie people, honoured him.

The amah took me to the kitchen. Feng had left for Great World hours before, where he indulged himself in the make-up department with a shave. His face lathered up, he’d watch the make-up girl slowly scrape at his chin. It made them nervous, the way he scrutinized them, and he probably enjoyed it, that complex interchange, him scowling at them, the girls holding razors to his face. He liked his female employees to be frightened of him even when they held razors to his throat. It was potent and erotic.

Ah-niu served me coffee in the kitchen on Becky’s overly fancy English bone china. The nursemaid brought the baby out for me to see. I held Amanda in my arms for a few minutes, and the baby considered me with grave concentration. Amanda tended to scowl, as if she were finding her first six months on Earth unsatisfactory. She looked about the room then back at me and eased into a noisy cry, so I handed her back to the nursemaid.

Becky could have no more children. It was cruel to have lost the ability. The hysterectomy had left Becky despondent and often prompted spontaneous crying. Feng said nothing on the subject to me — I was not family and I was a foreigner. He outwardly showed only ineffable stoicism, if not sympathy, for his melancholy wife. Ah-niu told me that Feng had become angry with Becky following the operation. The best that he could muster was to sigh impatiently and, once, he told Becky in front of Ah-niu: “All this crying will prepare you for Long Ago and Far Away. ”

Ah-niu told me that Becky had received numerous letters that bore postage stamps from the People’s Republic of China. They had been clumsily stuck on - Chinese stamps had no glue on the back; correspondents had to slather paste on them from a brush bottle in post offices. Ah-niu did not know who the correspondents were, possibly activists soliciting her help or condemning her as a tool of the British. She said the letters had been addressed to “Expel Imperialism City.” In the insanity of the 1960s, Red Guards flooded into the southern city of Canton, 130 kilometres northwest of Hong Kong. They were a paramilitary force of malevolent teenagers who sought to help Mao regain control of the Communist Party from his rivals. But they became large and potent and they went berserk, making mad orders — the madder the better, as far as they were concerned. They invaded the Canton post office and issued a decree that no mail bound for the British colony should be delivered if it bore the name “Hong Kong.” They had unilaterally and spontaneously renamed Hong Kong “Expel Imperialism City.” Any postal workers who dared question these hysterical zealots were beaten ferociously, sometimes to death. There was other madness in Canton. The Red Guards decided that since red was the colour of the Communist Party, all traffic in Canton streets should proceed on red and halt on green lights. They would stand at intersections and scream at baffled and intimidated truck drivers who had stopped on red at the city’s few traffic lights: “Go forth with the Red Sun of the Communist Party!” the teenagers screamed. “Go! Go! Go!”

“Did Mrs. Feng have any doctor’s prescriptions?”I asked Ah-niu in Cantonese. “Western-doctor medicine?”

She shook her head. “Only painkillers after the operation,” she said. “But they ran out and she didn’t renew them. ”Becky preferred Chinese medicines over Western drugs, which she said were harsh and had no underlying unity of purpose.

The first time I met Becky was in the autumn of 1948.1 was new to Hong Kong and still enthralled by the sights and smells of the colony. I’d gone over to Kowloon from my dismal flat on the island to tour the big shrine to Wong Tai Sin. It stood at the top end of the peninsula, just below the great hills that ringed the north side of Victoria Harbour. From the steps of the shrine you could see all the way down to the tip of Kowloon and in late autumn, when the air was sunny and clear, it was beautiful. The shrine was always packed because the god Wong Tai Sin had gained a fabulous reputation among refugees for coming to their assistance. His advice, conveyed through a canon known as the One Hundred Poems, led one man to start a small business sharpening knives on a sidewalk and now he owned a big shop in Laichikok. A refugee woman took Wong Tai Sin’s advice on whether to marry a certain man. The poems had indicated marriage, which turned out to be successful and there were many sons.

I had grown a very red moustache in a bid to look older than twenty-two. I wore a Harris tweed jacket, which I clutched to my sides as I dodged platoons of beggars on the steps to the shrine. Mounting the curving stone staircase to the main courtyard of the temple, I saw the gate of the temple, with its slouching tiled roof and pillars. Inside hundreds of people held clumps of smouldering joss sticks in their hands as they knelt before a stone effigy of Wong Tai Sin. Some were in rags and looked truly in need of miracles. Others wore fine woollens and silks and looked as if they ate meat three times a day, and not the gristly cuts. In among them was a slender young Chinese woman in a Western-style white dress, cinched at the waist and cut low around the neck, a cheap, vulgar thing she’d probably bought in a back-street market stall, not a fine British dress shop. She was very young, very beautiful and she knelt there among the poor and destitute, the affluent and well-fed, clutching a great fistful of joss sticks. She batted the smoke away with her free hand and coughed irritably.

She saw me looking at her and winked, a shocking gesture from a respectable Chinese girl back in 1948. She examined me, my tweed sports jacket and oyster-coloured trousers and probably concluded (righdy) that I was harmless. “Hello,” she said in English. She was truly a lovely young woman, even in that poor-quality dress. After she finished her supplication she asked me to help her insert the joss sticks in a huge sand-filled urn. She gave me half of them and we planted them together.

“What do you want?” she asked.

I was flustered because I thought she was accusing me of trying to pick her up.

“From him,” she said, gesturing over her shoulder toward an oversize stone effigy of a bearded man painted with bright enamels. “From Wong Tai Sin?”

“I was just curious about the temple,” I said.

She fired out her arm and extended her hand in a put-’er-there way she must have seen in an American movie with Eve Arden in it. “Becky Chan.”

I shook her hand. “My name is Paul Hauer.”

She repeated it several times to make her tongue get used to the feel of it. “You’re a tourist?”

“No, I live here. I work for a newspaper.”

“What do you do for it?”

“General reporter.”

“A newsman,” she said. “Some glamour.” We finished putting the joss sticks in the sand and she clapped her hands together. “Uck, everything’s so dirty here. Hey, I got a story for your newspaper.” She told me that the temple was far holier than the crowds, smoke, noise, peanut vendors and playing children made it appear. “Even the Turnip Heads had to pay to harvest the bamboo stands that surrounded the temple when they were here,” she said. “They were so in awe of Wong Tai Sin.” She was talking about the Japanese forces during the Second World War, using the defiant slang the Cantonese used for their tormentors in the darkest years of occupation.

“Let’s go ask the god for advice.” She led me toward an arcade covered with corrugated tin roofs. Inside were fortunetellers. “You want anything from the god today?” she asked. She turned and looked at me for a second then asked, “Do you see everything in blue?”

I didn’t understand.

“Your eyes are blue. So is everything you see blue?”

I asked her if she saw everything in brown.

She smiled beautifully and rolled her eyes to the side. “Hey, is your hair naturally blond or did you dye it? I’d like blond hair too. It would be fun.”

I couldn’t resist her. She was jaunty, vivacious and a bit out of her depth with her forwardness. She must have helped my frail ego by showing interest in me then appearing vulnerable with her naïveté. I went with her to the sheds at the side of the temple. There sat sage fortune-tellers, smoking long metal pipes and examining the One Hundred Poems for answers to the questions put to them by subscribers. She sat before one man who had a couple of long wiry hairs sprouting from a mole, considered decorative, like bonsai trees, I suppose. I stood by while she fished out a couple of coins from a pasteboard purse that looked like a miniature version of a child’s lunch bucket. It was pale pink and so tacky I couldn’t help but smile. She was sweet, but the girl needed tutoring in Western fashions. I had enough sense not to tease her about her clothes.

Becky put her question to the fortune-teller. He gave her a tin canister, perforated at the top, which held a number of sticks. She shook the canister and a single stick rattled out through one of the perforations. The fortune-teller looked at it through his spectacles, sighed in bland recognition, then looked through a book for the corresponding poem. He read it aloud to her in Cantonese and then gave her an interpretation. All the while she listened very intently, very gravely, asked a few questions in Cantonese and then thanked the man. I stood by and watched without comprehension. When she was done the fortune-teller gave a jaunty little wave and considered me, thought I might be business and beckoned me over. I just waved politely and escorted Becky back to the main compound. “What did you inquire about?” I asked.

She gave me a cheerful smile. “French high heels,” she said. “I want them so badly, so I sought advice on how to get them. They’ll be lovely when they arrive.” She glanced up in the air then winked at me again. “They’ll be here any time soon,” she said, as if they were about to plunge out of the sky and hit the ground in front of her.

Becky told me that the fortune-tellers in their decrepit sheds were the principal conduit to Wong Tai Sin’s munificence. With explicit instructions from the One Hundred Poems she had, she claimed, overcome a clumsiness that had confounded her parents. They were Mother and Father Chan and they had adopted her out of the Door of Hope Orphanage and put her to work in their Cantonese opera troupe. She said that through his actions her father had taught her to come to Wong Tai Sin and ask for help.

That day in Wong Tai Sin Temple, while refugees were praying for a roof over their heads, redemption from illness or just plain money, Becky was clapping her hands in divine pursuit of French-made high heels. Or so that’s what she told me. I couldn’t understand Cantonese yet so I didn’t know what she had spoken to the fortune-teller about. I had to laugh at her frivolity about shoes amid the squalor of Kowloon. I gave her my business card and invited her to call. “Hey,” she said, slapping my arm with the back of her hand. “Is this a pick-up?” I blushed fiercely and she laughed. “Hey! Do that again. Change colour like that. Can you turn other colours? Green or blue?” We went down the steps and beheld the view of Kowloon below, a panorama today lost behind a wall of modern high-rises. She stopped before a beggar child and gave him a coin.

She looked back at me and said, “Next time I will pray to Wong Tai Sin for a telephone, so I can call you.” I didn’t know her yet so I couldn’t tell just how thin the top layer of her frivolity was and how networked it was with fissures, like crackle-glazed porcelain. It was a such fine day in October 1948 and we were both young and more adventurous than we realized. She seemed like a fun person to me, as I said in my diary that evening, and I probably seemed exotic to her. So we began to pal around. It never occurred to me to date Becky. The fun we would have in those early years would go a long way for both of us.

I took Becky and a party of others — there was a BOAC crewman I wanted to hanging around with that year, an American reporter, and two other actresses who worked for the Southern Electric Film Company - to a gambling den. I thought it would be a fantastic adventure. The women said they didn’t want to go, but the presumed authority of their Western male friends got the better of their judgement. I took them to a back street in Hung Hom, just past the old ferry dock, where there was a fetid old shophouse next to the Hong Kong United Shipyard. The shophouse sold cheap plastic housewares, but its principal activity was illicit money-lending.

I remember that one of the Southern Electric actresses started to shop for plastic tumblers until we gently tugged her to the back of the building and up a narrow set of stone stairs. You had to go through the living quarters of a small family to get to the gaming room. There was a granny lying on a cot in front of the secret door. Whether she was actually ill or just putting on a lucrative act wasn’t clear. You had to wait while her teenaged grandsons lifted her up and aside. “Not again,” she would mutter when she got hoisted out of the way. “I’m so tired, ” she said, holding out a leathery palm for a coin. Upstairs we laid down one-dollar bets and thought what a smart set we were, until the police arrived with a battering ram for the steel door. I recall running down the back stone steps with Becky, while she and three other actresses shrieked, “Fai-ti, lah! Hurry! Hurry!”We escaped.

Becky became very quiet and didn’t speak to me for a long time. I hadn’t realized that my idea of boyish fun would frighten her so. It dawned on me belatedly why. She had just hustled her way into a job at Southern Electric, and if her bosses had found out about the raid they would have fired Becky. Her job was more important to her than any night of fun and I apologized for causing her such worry. I should have thought better of the risk I put Becky and the other women in. Stupid of me, but then I was a very injudicious young man.

Seated in Feng’s kitchen, drinking his coffee, I asked Ah-niu if Feng had been cruel to Becky and she said no, although I suspected that she was merely being decorous. She didn’t have to tell me Feng could be cold and dictatorial. When he thought that no one was listening, Feng could speak to Becky with a cutting meanness. At a banquet celebrating Great World’s fifteenth anniversary I heard him mutter to her, “You used to be so pretty. I think you’re gaining weight. You know how the ’Scope lens stretches your face. You’ll look even fatter up there. ”Becky only looked at her coffee cup and nudged it around the table, pretending nothing had been said.

Ah-niu excused herself and hooked a rubber hose from the kitchen cold-water faucet. She ran it from the faucet to the first of four large olive-green plastic barrels in the adjacent pantry. She turned the water on and began to fill them. “It’s our day, ”she said. While the water splashed noisily into the first barrel I asked her if Feng had told her anything about Beckys melancholy and she replied, “Mr. Feng never speaks to me about anything other than household duties. ”

We said nothing for a while and I waited for her to fill the barrels. That summer, Hong Kong endured the worst drought in its history. We were subject to strict water rationing by the government: four hours of service every other day. My shower head would be gushing assuredly when I stepped beneath it, but just as I put shampoo into my hair, the water would dribble off and give a disappointed gasp. I usually forgot to fill my water barrels on the day my neighbourhood had its turn so I went without. My kitchen sink filled with dishes and glasses and I would come home on a water day to find I’d left the tap open and there was water splashing everywhere in obscene and chaotic abundance. In the slums of Hong Kong Island and Kowloon, women shoved one another in ill-policed queues next to forlorn little public stand pipes, their only source of water. They’d spend the better part of a day filling up the square metal cans and taking them back to their shacks in the hills then coming back for more. The drought had left Hong Kong reservoirs nearly empty. You could see them from the hillsides: sadly reduced ponds edged with steep chalky orange banks, wrinkled and arid in the summer sun. There had been no typhoons to replenish the reservoirs and a secondary source of water, through a pipe from China, could not be increased. No local bureaucrat in south China would dare make a decision on increasing water without worrying about whether he was going to be charged with aiding the British imperialists in Expel Imperialism City.

At most times, China seemed as far away as Europe from the cares of life in the British colony. China nevertheless could occasionally intrude on our lives with dramatic impact. My good friend, Sergeant Jack Rudman, faced down increasingly militant labour agitators who had been emboldened by bullying Marxists in the nearby Portuguese colony of Macau. Eager to gain favour with Maoists on the Mainland, Hong Kong leftists launched the biggest period of unrest Hong Kong has ever known in peacetime and Jack was getting it in the face. While I covered stories about demonstrations, riots and bombings for the China Telegraph, I would see Jack and his men in the Emergency Unit, firing tear gas into crowds of young people waving Mao’s Quotations. In turn the leftists would hurl back anything they could lay their hands on: flower pots, sharpened bamboo spears, metal bars, rattan chairs and all sizes of stones. In one riot an enormous sledge hammer came whirling through the air at Jack. It missed him, but struck a Chinese colleague, breaking his shoulder.

I would call Jack every evening to see if he was all right. Sometimes he was too tired or weary of stimulation even to take my calls. He showed all the tedium that came from too much excitement. “The only thing I want to do at the end of the day,” he said, “is go back to quarters and wash the tear gas out of my hair. It’s a simple thing, and I wish more people realized that. Please don’t call again until the weekend.” I felt like a nuisance and I was a bit ashamed of my preoccupation, as though I were a fretful old woman.

And so I devoted myself to my news stories. The agitators’ disruptions to daily life were often ingenious: teenaged boys boarded buses and released bags of snakes, creating a blind panic that almost resulted in a crash. Little schoolgirls, hounded and intimidated by leftists, were instructed to position themselves between the demonstrators and the police. They would stand there with their arms linked, caught between two determined forces. You could see them crying in terror and wanting to bolt. The Communist press was standing by to witness a brutal police attack on little girls so it could publish stories and photographs of the cruelty. I heard one leftist hectoring a little girl who was about to break ranks and flee, using a threat understood only by the two of them: “Li-li! Remember what I warned you! I will tell your father what happened!”

Ah-niu finished filling the water barrels in the pantry and placed lids on them. She put the hose away and looked out the tiny window over the sink. There was nothing to see but the wall of the house next door. All at once she burst into tears and turned her head away from me. “Gangsters have kidnapped her,” she said.

She wiped a handkerchief over her face and tried to busy herself in an already tidy kitchen. She plugged the electric kettle back in to make more coffee.

“How do you know that?” I asked her.

“I don’t. It just makes sense, ”Ah-niu said. “She wouldn’t just run away. She has to work hard. She has a new baby. She has many responsibilities.”

“She wasn’t happy. She hasn’t been happy for years,” I said,

Ah-niu thought the remark irrelevant and it showed how far apart our worlds were. “What is happiness? Happiness is for the idle. She has a family to feed and care for. She has a hard job.”

“Do you think that Mr. Feng has hurt her?” I asked. “Do you think he arranged for her to go away?”

Ah-niu pulled the plug of the kettle out of the wall. “Perhaps,” she said. “Mr. Feng has been very cold.”

She brought me a fresh pot of coffee. I drank a cup in silence. When she thought I wasn’t looking, Ah-niu sneaked her hand into the sugar bowl and took out a single cube. She put it into her mouth, closed her eyes and concentrated on the sweetness. Becky did the same thing all the time. The gesture made me think of her.

Ah-niu let me look around some more but she was growing nervous with the length of my stay. I was snooping about the Feng household shamelessly. Ah-niu walked behind me to scrutinize my every move, polishing a sofa table after I’d touched it, as if Feng would lift fingerprints when he got home. She was keenly aware that my presence could get her fired. I went into the main bathroom and opened the medicine cabinet. Inside were little pots of make-up creams, lipsticks and eye shadow. There were also capsules of Peking Royal Jelly, a box of purgative tea, aspirin, mouthwash and deer horn extract. Under the sink, in the cupboard, there were a few boxes of Hazeline Snow face powder and five aerosol cans of hair lacquer.

I quoted an old saying which Ah-niu took to and she repeated to herself: “Beautiful women are ill-fated.” It was what women in movie audiences explain to themselves on why the blessedly glamorous really are damned, and how they, the ordinary women of the world, have the real advantages.

Feng was an inveterate showman who loved to trot out his pretty wife at lavish parties, like a prize chicken. In Cantonese slang, associating women with chicken is an obscene comment, but in my poisoned opinion not at all inappropriate for Feng. Like Cecil B. de Mille, whose movies condemned extreme depravity but showed it in loving detail, Feng Hsiao-foon knew how to indulge the public’s sex fantasies while vigorously decrying them. Many of his “decadent” Mandarin-track pictures were about nightclubs, rich people’s idle cares, airline stewardesses, singers and the police. In films such as Pink and Deadly or Don’t Bargain with Fate, Becky plays night club singers who turn their back on normal domestic lives with husbands, children and in-laws so they could perform on stage. It is pre-ordained that the adventuring woman head ends in ruin, reassuring the audience about their mundane domestic arrangements, but the public got a good gawk at the fun she had before the end. Yes, beautiful women really were ill-fated.

Ah-niu’s anxiety peaked when I went into the Feng’s bedroom. It was wildly over-decorated in a Louis XIV style, with blue satin cushions and oppressively over-carved furniture that Feng and Becky had shipped in from the United States. I sat on the edge of the bed and looked at the items on Becky’s night table. There was a script for an upcoming picture. Recorded at the bottom of the title page, in Becky’s hand, was idle gossip of no great importance. So-and-so spent $4,000 on legal fees to petition for divorce. So-and-so’s wife is pregnant. It told me nothing about Becky. There was a Royal Doulton figurine of a woman holding the edge of her billowing yellow dress. Her right hand was missing, chipped off probably when it had got knocked to the floor. There was a big book of Chinese medicine, detailing cures for various ailments. Chinese cinnamon to treat yang-deficiency in kidneys. Clove tree to counteract vomiting. Powdered oyster shells for heart palpitations. Wild turmeric for chest pains and semi-conscious states. There was no bookmark, no annotation, nothing to indicate just what Becky had been looking through these medical journals for. It told me nothing more than she had a general interest in disease, illness and its treatment. It was the first time I’d ever set foot in her bedroom and I noticed something missing that caused me a moment of sorrow and emptiness. Despite our two decades of close friendship, there was nothing in this room, or anywhere in Becky’s home, that showed any physical evidence that I had a place in her life. No little photo of me in a collection of similar pictures on a side table, none of the trinket gifts I’d given her over the years. I sighed and put the books back on the night table. Ah-niu had become so anxious about my sitting on the bed that when I stood up she frantically swept the creases out of the bedspread.

I thanked Ah-niu for her cooperation and left. I stepped outside. The day was growing very hot. I glanced up at the words over the front door, “Bricks and Mortar of the Nation.” Chung Hsiang came to life again, for just a moment, when I came out the front door. She barked and slobbered furiously, trailing me to the metal gate and, once satisfied that I had closed it behind me, turned and went back to the shade in triumph.