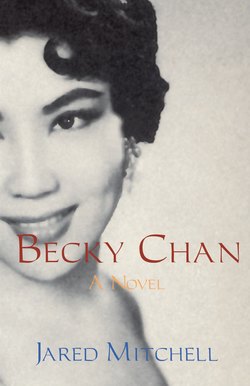

Читать книгу Becky Chan - Jared Mitchell - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FOUR

ОглавлениеHow different Becky’s movie roles were from the beautiful but gawky and naïve young woman I first met back in 1948. Both Becky and Hong Kong offered a new start for me, after a bad life in Canada. Like the refugees from China, I found a safe haven in Hong Kong, far from personal turmoil. I had once dreamed of a career as a singer in Canada (I referred to myself as a “song stylist”) but I never got further than paying for two years of university at United College in Winnipeg by performing part-time. I appeared during intermissions at the Uptown Theatre, a cinema on Academy Road. Between the shorts, co-feature and the main film I would rise grandly out of the basement on an elevator platform, surrounded by an eight-man orchestra. I sang dance numbers, my specialty being animal songs. I performed “Arfie the Doggie in the Window,” “Mr. Bluebird,” and “Wolf Call,” which I spiced up with realistic howls. While I performed, little gold lights in the blue ceiling of the Uptown would twinkle like stars.

My father disowned me, quite violently. A letter from the United College dean’s office arrived at my home, addressed to my father. It stated that the college had expelled me. My father disbelieved it at first and made an increasingly humiliating telephone call to the dean’s office, hotly denying the charge of “personal indecency.” After my father raved on the telephone to the dean about how preposterous the sexual allegation was, I quietly took the phone from his hand and hung it up. “It’s true,” I said very quietly. Then the police arrived, I was taken in and formally charged. My father grew furious, first with them, then with me. His doubts began to spread around the edges of his confidence in me like slime on a favourite swimming hole. In silence he drove me home from the police station on James Avenue. I wanted to bolt from the car when we crossed the Redwood Bridge and dive into the brown waters of the river, so frightened and ashamed I was. The idea actually fascinated me for a few minutes. When we were home again, I had one of those scenes everyone dreads: the increasingly hostile examination by the father, the palliative cups of tea from mum, her feckless attempts to calm the father, the steadily rising timbre of his questioning. It ended with him giving me four or five good hard smacks on my face with his fist. I fell clear over the back of the chesterfield. Mum got a raw steak from the fridge, then started to cry quietly as she pressed it to my cheek. It’s been half a century since then, and I still don’t like to talk about it.

I had been caught in bed with my history professor and a mechanic who worked for Grey Goose Bus Lines. We had been introduced to one another through a very private and secretive circuit of men in Winnipeg into which I had only just insinuated myself. The Winnipeg police (who in contrast to their counterparts in Hong Kong had very little with which to preoccupy themselves) had been keeping an eye on the professor for some time. They burst to his house, I yanked the sheets over myself, the professor sputtered about search warrants and the bus mechanic fell off the far side of the bed. The professor went to jail briefly. As for myself and the mechanic — I remember he had bus grease under his fingernails and it made him terribly exciting - we were given suspended sentences. The whole city learned of it somehow. Winnipeg was a hostile place. No man even used an umbrella back then, since such devices were considered effeminate. And if a simple black umbrella were a lacy parasol in the minds of right-thinking Winnipeggers, sex with another man was beyond abomination. People whispered when I walked down Portage Avenue and some morally outraged young man in front of the Lyceum Theatre threw a Coke bottle at my head.

My father informed me that I was not his son and that I was to get out of his house by the week’s end. I went to my room, examined the relics and mementos of my recently concluded childhood and had a quiet cry. When I finished, my mother knocked on the bedroom door and pushed our ancient black Labrador, Duke, into the room. “He wants to see you for a while,” she said and closed the door again with barely a sound. I was so grateful for Duke’s cataractic gaze, his white muzzle on my lap.

As I told myself with brave nonchalance the next day, my fortunes lay elsewhere. My mum put me on a Canadian Pacific train to Montreal; my father refused to take time away from work to see me off. While we waited in the depot she kept scratching Duke’s neck and talking only to him. “Poor old Duke,” she said. “You’re so very sad that our Paul is going away, aren’t you? You don’t know what you’re going to do, do you?” She didn’t always talk exclusively to the dog; only during times of personal crisis. Everything of significance went through the dog. She walked Duke up to the train platform to see me off. The train pulled out of the CPR station in the middle of a blasting rain storm, and I felt about as wretched, ashamed and condemned as any twenty-one-year-old boy could.

It was the era, of course, but every time I saw a soldier, sailor or airman on the train I felt even more intensely wicked. A whole pack of them boarded at Fort William, looking so brave and heroic, even when they told each other obscene jokes or picked their noses. These were men who served their countries and honoured their families. All I had done was disgrace mine through sexual perversion. My carapace of guilt only began to break in Montreal, where I looked for work as a nightclub singer. Some of the irre-pressibility of youth returned when I saw the boîtes of St. Catherine Street. It proved more difficult to break into nightclubs in Montreal than I’d expected. Managers didn’t think that intermission singing in Winnipeg cinemas was sufficient, and more than one actually walked out during my audition song, a childish anthem called “Let the People Sing” that was utterly inappropriate for Montreal’s champagne-and-gun fire nightclubs.

I did not stay long in Montreal. I managed to get myself run out of town there too. I was caught in bed with a nightclub dancer. He was thrilling, he was muscled, he was from Martinique and he called himself “Othello.” He let me wear the sharks-teeth necklace he used in the Folies Nègres routine at the Club La Framboise and he showed me how to do the splits. Even more thrilling than Othello was getting caught in bed with him by the police. Othello knew his way around Montreal and had the sense to lick off five ten dollar bills from a small roll in his pocket for the good constables. I didn’t, so I was arraigned on gross indecency yet again. While I was awaiting trial I went to the Canadian Pacific office and bought a ticket on the next boat for England. A few months later, from Hong Kong, I wrote to my United College history professor, who was now lecturing the cons in Stony Mountain on Benjamin Disraelis career and dodging them in the showers, and told him that I had decided to go east. I just hadn’t realized just how far east I would go.

I arrived in the colony feeling renewed, blue-eyed and hearty. With the last of a lot of money my mother had given me secretly, I bought a ticket on BOAC to the Far East. My idea had been to become a foreign correspondent in Japan. When the BOAC flying boat splashed down in Kowloon Bay, the British authorities put me off because I had no accreditation to continue on to U.S.-occupied Japan. In Hong Kong I found a job with the weakling rival to the South China Morning Post. The China Telegraph was a small broadsheet that the managing editor called “a working man’s newspaper.” The managing editor was a man named Trebilcoe, a veteran of second-rate newspapers in Britain and India, and, like his colleagues around the world, he was going to pieces on alcohol. He had a pink face and his grey-blond hair was malodorous. You could smell gin on his breath at ten in the morning, thanks to a twenty-sixer in his desk’s lower drawer. “May your career at the China Telegraph be a long and restful one,” he said on my first day. This wreckage was no place to make friends for an eager young man who had just rescued himself out of Canada.

Mr. Trebilcoe must have invested in me the last of his tattered hopes because he made sure that I was always busy, covering every sort of story there was, as if I were a surrogate fresh start for him. Mr. Trebilcoe was one of a breed of itinerants who spent a few years in any city in Asia that had an English-language newspaper: the Bangkok World, the North China Herald, the Straits Times, the New Straits Times and one paper I thought had a most charming name, the Borneo Bulletin. After editors like Mr. Trebilcoe grew tired of the town and the inner trembling about their lives became external, they would move on. Such a life and the deprivations and internment of war had left these men preternaturally aged, tired and bibulous. At the time my perception of Mr. Trebilcoe varied between being picturesque and a pathetic nuisance. I was more than once dispatched at five in the afternoon to scour the bars for him. I found him in the back of the Seventh Heaven Restaurant on Wyndham Street, leaning over a triple and close to tears. “I didn’t work today,” he said, visibly shaking and hunched forward, “but I’m sure I would have if I had.” I guided him down the Wyndham Street sidewalk, a treachery of intermittently placed sloping steps, back to the China Telegraph, where he functioned for the remainder of the evening.

Hong Kong was sports-mad back then, and every day the China Telegraph featured two whole pages of local amateur sports round-ups: cricket, rugby, soccer, softball and field hockey. I was responsible for contributing hearty coverage of local matches.

| The China Telegraph |

| Sport and Sportsmen |

| The stands at the Police Sports Ground in Boundary Street were overflowing yesterday when South China B played Kowloon Motor Bus. KMB attacked from the start, and their finishing touches in front of goal were spectacular. Just before half-time, Lee Chun-fat of KMB held the shot but the ball rebounded into play. After the interval, South China B began attacking and in the eleventh minute Colin McLinn opened the scoring.... |

Beyond the sunshine world of Westerners in the colony there were darker things in 1948, stories I covered usually with a Cantonese-speaking interpreter and, as I learned more of the dialect myself, on my own. Far from British arrogance bred of easy accomplishment, and even further from the Chinese merchants and professionals who were, even then, quickly growing rich, were the refugees who huddled into Hong Kong from the endless turmoil in China. I could never have imagined, when I first arrived in the colony, the squalid depths to which people could sink on those hills covered with packing-board shacks. It is hard for young people in Hong Kong today to realize that their parents and grand-parents came close to extinction in those harsh years after the war. Husbands pimped their wives and daughters to make enough money to fend off starvation. A paternal nation, Father China, had collapsed and its spiritual casualties were those heads of households strewn over those hills, selling their wives, stealing food, killing one another and finally giving up and fleeing their families. It was at this time that the intolerable pressures of life drove many despairing men to one of the most hideous of fates, heroin. You would see them gathered up in police raids, starving stick men, unable to close their mouths, their eyes rolled up so only the whites showed.

I covered stories at the Criminal Sessions, including an all-too-frequent crime of “acid throwing.” Mrs. Cheung Mei was accused of tossing hydrochloric acid at another housewife in Kowloon City in a case of convoluted neighbourhood tensions gone out of control. It was hard to disentangle who had done what to whom. Then there was a high-class prostitute from Shanghai known obscurely to her clientele as “Coca-Cola,” who was found poisoned by an angry customer in her Happy Valley house. Mr. Trebilcoe instructed me to identify her discreetly as a “cabaret artiste.”

For the first few months I stayed at the Tsimshatsui YMCA, then known as the “European” Y. All winter I rode the Star Ferry every morning, travelling second class to save money, and freezing on the open decks. In my leather briefcase was a flattened roll of toilet paper for use in the ill-equipped China Telegraph wash-rooms. The newsroom usually smelled of rotting paper, even in chilly winters, when you had to wear fingerless gloves to type. The inmates of the European Y were much poorer and often far stranger than the Oriental idea of what a European was. Some were older men excessively preoccupied with Edwardian poets such as Siegfried Sassoon. And there were Anglophillic Chinese bachelors who had lived abroad and were capable of breaching the racial barrier by “taking rooms” at the European Y. They reincarnated themselves as cut-rate English gentlemen with authentic eccentricities. One man was fanatical about railways. His eyes actually blazed and he addressed me in an over-rich Anglo-Cantonese accent about the nature of mixed trains. “That is to say, trains that mix passenger carriages with goods vans. One never attaches livestock vans to mixed trains. It’s just not done because of the odour that would attend passengers. Yet in the evolution of mixed trains not all the world’s railways came to this realization quickly. Our own Burma Railways, for instance ...”

The British residents of the Y were no less inimitable, and at best distant, decrepit relations to more refined commercially important persons from Britain. These fatigued lower-downs in print dresses and serge pants gathered in the YMCA canteen and waited for their meals with a freckled poise, looking pretty shabby. Between them and the doddering, comedie Chinese waiters they called “boys,” it was difficult to assess who was more likely to drool over the plates of food. “Oh, Jess!” two women crowed in unison on the first morning of my residence. They were greeting a third who made her way into the canteen with the benefit of a cane. “How’dja sleep, luv? Poor Jess, you look all in already.” Jess, whose badly mottled skin reminded me of marbled cheese, came and sat down and began to enumerate all the miseries of trying to sleep in a tropical climate. What she and the other women were doing in Hong Kong I never found out. Probably visiting their sons in the British Forces garrison or, like my Mr. Trebilcoe, possibly castaways who had roamed from colony to colony until they were out of money and hope. Either way, here they lived and every morning discussed their miseries with the intensity of young sports reporters at KMB games.

Initially I was very lonely and still really very sad over my father’s dam-burst of hatred for me. He never, in the rest of his life, wrote me with any indication of reconciliation, and I guess I never made much of an attempt to seek forgiveness. It was over between us, and it was over completely. Even in 1967, almost two decades after, it still ate at me with regret and, increasingly, unfocused anger.

The first flat I rented was in Causeway Bay, then a sleepy neighbourhood on the edge of an extremely unsanitary typhoon shelter, a little basin of breakwaters stocked with decrepit fishing boats and excrement. My apartment toilet was criminally mischievous: it flushed efficiently enough but then several minutes later would suddenly regurgitate its contents up through the drain of the bathtub (this sometimes happened while I was entertaining guests). The apartments builder had prized privacy above views. He had fitted the windows with frosted glass, and I was left scratching my head as to what was going on around me. Wavy wrought-iron typhoon bars on the inside made it impossible to stick my head out the casements and see what was out there. At night I could hear mah-jong games clattering in the next flats and the voices of the players, but I never saw who the players were. The streets were often just as unyielding. I passed a pawn shop on Fleming Road in Wanchai which had saloon-style louvred doors just high enough so that I couldn’t see inside. I was too shy to go inside to look but I could hear clients haggling with the pawnbroker, their voices rocking off the green stone walls of the shop. When a deal was consummated, the pawnbroker brought his chop down on the sales agreement with a clap. Someone with a small treasure wrapped in an old smock once bustled in through the spring-loaded doors, affording me a momentary view of the brokers in their cages. But the doors swung back and hit me in the nose, bloodying it.

My loneliness amid the fusty wrecks who worked for the China Telegraph propelled me into making friends with a new generation of Hong Kong people. In need of company my own age, I went to a few bars in Wanchai where the matelots hung out, but the fighting and the bar girls made me uncomfortable.

Through the press club I met young Europeans and Chinese who mixed freely at inter-racial parties. This was considered brazen and unwise by our European and Oriental elders so we felt stimulated even more to flout their expectations. Being young.

I started one evening with some work-mates from the China Telegraph and the South China Morning Post. We had drinks at the Press Club in Central, watching the tinhorn society come and go. An American who did a music program on radio station ZBW came in wearing a navy blazer on his shoulders, affecting a European look that took some imagination to appreciate. He came with a young woman named Arden Davis who worked in the public relations firm of Feltus and Robertson and she was an exception to the cheap pretenders in the room. She was a smart creature in a beret and white angora sweater that should have been impossible to keep clean in the Orient, where dirt clung to everything. I asked Arden how she did it. “It’s because,” she said, signaling the waiter for a Manhattan, “Americans are among the great dry-cleaning peoples of the world.” I adored her immediately. She had the best teeth I had ever seen. Arden, who became a life-long friend, contrasted sharply with the dishevelled-looking woman who edited the women’s page of the China Telegraph. Mildred always looked like the heat had wilted her, even in winter; her hair was plastered flat on her head. After a little coaxing she suffered her male companion to order her a martini. He had on a bow tie and a coarse tweed jacket and corduroy trousers that he wore even on the hottest days of summer.

That evening, I ran into Becky Chan for the second time, at a party in Kowloon Tong. Arden, a few Post reporters and I stopped by the Hongkong Hotel for another aperitif and then popped into Mac’s Grill for steaks and whisky. We were a little tight and not at all comfortable on the ferry ride across the choppy harbour to Kowloon. We walked into the party with shouts to the hosts and bottles of Scotch under our arms. There were men and women, Chinese and Western, in every room of the house. It was only a few weeks after I’d met Becky at the shrine to Wong Tai Sin. She wore a cheap and ineptly made teal-coloured dress.

The décolletage came down in a V-shape, culminating in an unnaturally large artificial blue rose in the centre of her bosom. She was seated by herself and had just poured a bottle of Coca-Cola into a tumbler. She uncovered the sugar bowl on the tea set next to it, spooned sugar into the Coca-Cola and then tried to dissolve it with a vigorous stir.

“You’re making quite a sweet drink there,” I said.

“I like it this way. It brings out all the flavour,” Becky said from the sofa. “You’re the guy from Wong Tai Sin, aren’t you?”

I was glad that she remembered me. “Did you get your French heels?” I asked. She held her feet up and showed them off with such a gleeful look. She hunched her shoulders and giggled. Becky was bursting with energy and fun. Through the back window came the sound of a late-night train clattering up the Kowloon-Canton Railway toward China. I couldn’t bear watching her dump even more sugar into her soft drink.

Becky had just finished a picture at the Southern Electric Film Company, a tin-bucket little Cantonese studio. They had exactly three sets, which they painted and repainted. A skyline backdrop, frequently viewed through a fanciful window featured just a single building painted on canvas (Becky said they couldn’t afford more than one building). It was no joke about getting the job, though. She had pursued Southern Electrics managing director relentlessly, shoving her face in his car window when he arrived each morning at the front gate, almost yelling at him about what a good actress she was. She was a glamour girl standing in a gown in the dust beside a collection of shacks that made the studio. Coolies with shoulder poles and baskets full of night soil stared at her and muttered sexual speculations to one another. It wasn’t pretty or dainty, and Mildred would have found her grotesquely unladylike, but Becky aimed to survive.

Eventually, to get her out of his face, the Southern Electric man hired her at one dollar a day. She got a place to live in the studio dormitory with twenty-five other girls, sleeping on bunk beds. In the narrow spaces between the beds she’d perform a ribbon dance for the girls of the sort one saw in Chinese cultural movies put out by the Communist studios on the Mainland. Instead of orbiting long strands of colourful ribbons in great circles, Becky made do with two rolls of toilet paper that she slowly unrolled on her fingers. It was actually kind of artful until the spools of toilet paper slipped off the inner cardboard tubes and flew in opposite directions across the room, leaving her with nothing but the tubes on her fingers, which she stared at in mock confusion. The other girls loved it — they clapped their hands, screamed with laughter and called her “toilet theatre goddess.” It was all so innocent and earnest.

“Come and meet some people,” I said and made her leave her Coca-Cola. I introduced her to some European men and she charmed them just as she had charmed me, with big handshakes and American slang culled from the cinema. But when I guided her toward some Western women, she pulled back on my arm. “I left my drink in the other room,” she said, her voice getting smaller. I said to never mind that and brought her over to meet Arden and Mildred. Arden had good manners and returned Beckys howdy handshake in similar spirit. But Mildred assumed a dryness and spoke in a tiresome morgue. “How do you do, Miss Chan?” she said. “Tell us about your family.” Mildred pronounced it “fem-lee” and closed her eyes, feigning a London suburbanite’s idea of how aristocracy behave. Being in charge of the China Telegraph society pages meant Mildred had to set some sort of standard of behaviour. She continued in on Becky. “Are you a Hong Kong Island Chan or a Kowloon Chan?” And here Mildred gave off a great horsey noise.

“Mildred, what a weird joke,” Arden said, and Mildred’s face grew a little taut. Becky didn’t have a clue what Mildred was talking about.

She wasn’t finished, she still saw some sport in Becky. “What a lovely creation you’re wearing,” she said. Becky knew enough to be wary because she had closely scrutinized Arden’s up-to-the-minute bouclé sweater and silk skirt. Becky was learning that she was cheaply dressed. “It’s a bit loud, isn’t it, Miss Chan? And that big blue rose right here —”

“Let’s go get your Coke,” I said to Becky and guided her by the arm back to the other room. I glanced over my shoulder at Mildred but she had closed her eyes and stretched her mouth wide as if victory was hers. But as we left the room I could hear Arden revving up, something very direct, something like “you scrawny pompous cow ...”

Becky said nothing about it for that evening. But when I took her to dinner one evening she asked where she could read about Parisian fashions. We went to the City Hall library on a Saturday afternoon and went through current issues of Vogue. She snapped the pages of the magazines as she turned them and they gave off little firecracker noises. She stopped on a photo feature and pointed at a gown.

“How do you say that?” she asked.

“Givenchy.”

She repeated it with a Cantonese spin, “Ji-bon-ch’i,” she said. “Where do I get a Ji-bon-ch’i in Hong Kong?”

“They cost a fortune.”

“I’ll make one just like it.”

And she did. Using fabric she bought in the Gilman Street cloth market she refitted her wardrobe with homemade approximations of Givenchy and Chanel. She stayed up late in a corner of her dormitory at Southern Electric, sewing by hand with a peculiar technique of keeping her thumb pressed up against her palm. You couldn’t even see her thumb when she sewed. She also cadged time on the costume department’s sewing machine. In just over one month she reinvented herself as a chic young woman. If you felt the cloth with your fingers you realized it was second rate, but it was good enough to present to the tin horns.

The night I brought her in on my arm to the lounge at the Press Club the European women turned around and gaped at us. Arden rushed over and shook her hand. “Atta girl,” she said. “Knock these sad hens dead.” The European men jumped to their feet as we approached, their mouths forming little rictuses. They politely wished her good evening and made room for us to sit down. It was too wonderful. And Becky adopted a newfound hauteur, her make-up toned down, her hair grown longer and given a soft permanent wave. She even stopped yelling at waiters to come to her table, the way she had done when I first met her. Now she began her requests to them with a whispered “Mm-koi?”

This anecdote, the sort that Sunday supplement writers thank God for when it falls out of the sky at their feet, ended in a way that confused me at the time. Becky grew oddly unhappy with her new wardrobe. She said she didn’t deserve it. I had no idea what she meant. “Of course you do,” I said, “you made it.” But she didn’t wear the dresses for a while, choosing instead extremely plain Chinese dresses, like you’d see sales girls behind the counters in Lane Crawford wearing. Then one day, the mistress from the Southern Electric costume department (it was more of a back storage room than a department) asked to borrow the dresses for use in movies. Instead, Becky demanded rental fees. They dickered, agreed on a price and suddenly she felt much happier about her clothes. She started wearing them again.

Becky never lost her dry-eyed approach to making a living. I recall an incident at Great World, during the making of The Goddess of Mercy. A payroll clerk came on set and gave her the weekly pay-cheque. Resting against a diagonal board to protect her costume and head-dress, she snapped open the pay envelope and scrutinized the deductions hawkishly. There was just one penny too great a deduction. At once, the Goddess of Mercy stood up from the slant board and marched off to find Feng Hsiao-foon. She argued over the penny until he was fed up with her and ordered a corrected cheque cut. It was no wonder that the women refugees of Hong Kong had such a bond with her.

We found a camaraderie in physical complaint, Becky and I. It was in Hong Kong, during those early years that I first fell victim to crashing headaches that began with jagged violet lines pulsating before my eyes, followed by crippling pain and finishing up with some good hard retching. I sought out an American physician, who had a practice in Alexandra House. He diagnosed migraines and prescribed cold compresses. But the headaches were still agony. Becky found out about them over coffee one afternoon.

“What’s wrong?” she asked.

“Nothing.”

“What’s wrong?”

“A bad headache.”

“I knew it. I knew you were the sickly sort. I will make you better.” She insisted that I be treated by a Chinese herbalist at once. We couldn’t wait until I felt better: we had to take care of it right then and there. In my agony I boarded a bus with her and we trekked out to a Chinese medicine shop on To Kwa Wan Road in Kowloon City. Becky insisted we go there with the fervour of the mixed-train enthusiast at the European Y. No other shop would do. The place was nothing to look at: very dark and open to the street on one side. It had a lot of drawers, painted black and standing in rows right up to the ceiling, each one labelled in gold paint with a single Chinese character. The drawers contained dried roots, leaves, bugs and animal parts. The smell would have been pleasant if I hadn’t been suffering from a migraine, which magnified potent odours. The medicine man declared that my gall bladder was out of whack and prescribed prunella vulgaris to cool my internal fires and restore the flow of vital energy up to my head. I took it for years but with only variable efficacy.

The actual truth was that this young actress was not interested in cures, at least for herself. She was trying to make herself very sick, which sometimes worked and she would succumb to raging headaches and stomach pains. She confessed to such self-loathing, but only rarely. She would become lugubrious at lunar new year or during the Moon Festival. “Don’t forget,” she would explain, “I’m an orphan.” She would let the comment out as if it were a lone soldier banished from a heavily fortified citadel. She would let no more information forth. At first I pressed her but then I learned she was an intensely private young woman who rationed information about her real self. For most of our long friendship she told me little of substance, and never as a response to a direct question.

Becky loved movie-studio costumes and sometimes made little contra deals with the Southern Electric costumer, her faux Givenchy, for whatever they had in stock that month that looked like fun. When she was more confident about her appearance she arrived at a mixed-race evening in dark red lipstick and wearing a monocle and floral hat covered in a coarse veil — Chinese and Europeans alike recognized a spoof of Mildred, and we laughed knowingly. She especially favoured big ball gowns with enormous, fluffy skirts. She turned up in a taxi outside at a party in Kowloon Tong with a skirt so big it poured out the windows of the tiny cab like an enormous pile of rising bread dough. Inside the hostess’s flat, she used the dress to antic effect when the hostess, a tea service on a tray in her hands, looked about bewildered for the coffee table. “You’ve got it under there, haven’t you?” she said. “You’ve got the whole table under your dress.” And Becky would be standing there in that fluffy skirt, her hands behind her back, looking up at the ceiling, trying desperately not to laugh.