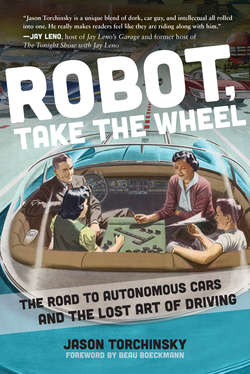

Читать книгу Robot, Take the Wheel - Jason Torchinsky - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1933: Mechanical Mike Autopilot

ОглавлениеEven though at the moment autonomous control for cars is the hot topic of (admittedly geeky) conversation, it’s worth remembering that airplanes have been flying themselves, more or less, for decades. At first glance this may seem counterintuitive—aren’t aircrafts dramatically more complex than cars? How do they routinely employ self-piloting systems that automobile makers are still struggling with?

The answer is pretty evident when you think about it for even a slight moment, and chances are most of you already realized it while reading that last sentence. It mostly has to do with this one indisputable fact: the sky is really big and really empty. Obstacle avoidance isn’t really that pressing a concern in the air. The chances of a cyclist pulling out unexpectedly in front of you in the sky are exceedingly remote; even if one did, they’d have much bigger things to worry about than getting hit by a passing airplane.

It’s sort of counterintuitive, but the air is a pretty forgiving place in which to develop autonomous piloting systems, even when accounting for the fact that if anything goes wrong the equivalent process of pulling over to the side of the road ends in a fireball on the ground. The sky is vast and empty, and that’s why fairly crude devices like the Mechanical Mike Autopilot, the first really practical aircraft autopilot, were so successful.

Autopilots like Mechanical Mike and most of the ones that followed are self-piloting in that they can maintain a set course and heading (that is, the compass direction an aircraft is pointed) and altitude, but they’re not concerned with any real obstacle avoidance, unless you count the ground, which is, admittedly, a pretty significant obstacle.

The first aircraft autopilot system was developed by Sperry in 1912, and in many ways wasn’t that different from the secret of Whitehead’s torpedo. The original autopilot, known as a “gyroscopic stabilizer apparatus,”7 was composed of a pair of gyroscopes, one connected to the heading indicator and one to the attitude indicator and controlling, via hydraulics, the airplane’s elevators and rudder. This early autopilot allowed a plane to fly level on a particular compass heading, freeing the pilot from many tedious hours of constant attention.

The first really significant use of an autopilot system came in 1931 when Wiley Post set a record for flying his Lockheed Vega airplane around the world in less than eight days. Post’s Vega had a more developed (than that original 1931 system, at least) Sperry Autopilot installed, which Post nicknamed “Mechanical Mike.”

For what it did, Mechanical Mike was surprisingly small, being only about 9 inches by 10 inches by 15 inches.8 The box housed two air-driven, 15,000 rpm (revolutions per minute) gyroscopes, one for azimuth/direction and one for lateral control of the airplane. Air-actuated servo valves connected to the gyroscopes hydraulically controlled the aileron, elevator, and rudder of the plane, giving full three-axis control of the aircraft.

Mechanical Mike required no electrical power, being entirely pneumatic, and only weighed seventy pounds. These were significant advantages over other autopilot systems, and Mike proved to be remarkably reliable. Mechanical Mike and other early gyro-based autopilot systems are significant in the development of autonomous vehicles because they represent the very first time a fully mechanical vehicular control system was trusted enough to transport passengers. The wide use of the Mechanical Mike following Post’s trip marked the first mass deployment of a situationally/environmentally reactive autonomous vehicle system, and, with nearly every major aircraft today employing a much more advanced version, represents the most common autonomous vehicle fleet currently in use on Earth.