Читать книгу Robot, Take the Wheel - Jason Torchinsky - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

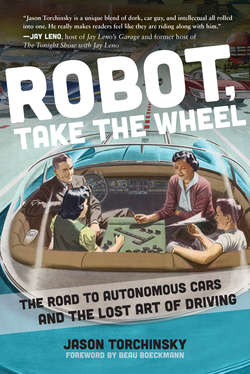

1945: Cruise Control

ОглавлениеIncredibly, automotive cruise control was invented by someone who didn’t even drive. In fact, it was invented by a blind man, Ralph Teetor, who came up with the idea after being annoyed at how bad his lawyer drove.11 Teetor was riding with his lawyer and having a conversation with him, and felt the car slowing whenever the lawyer was speaking, and accelerating when he was listening.

Nauseous but determined, Teetor wanted to find a way to keep a car’s throttle constant and free from the human driver’s fluctuation, and so developed cruise control, the first real semiautonomous assist device for cars.

Engine speed governors designed to keep an engine running at a constant speed have existed for over a century—you know those two spinning balls you sometimes see on old steam engines? That was a centrifugal governor, and also the origin of the phrase “balls to the wall,” since at maximum speed, those balls would be flung out nearly horizontally, or, you know, to the wall.

Balls or not, just keeping the engine at a constant speed really isn’t enough for a car cruise control system. Teetor computed the car’s actual speed based on how fast the driveshaft was rotating, and then used a bidirectional electric motor connected to the carburetor’s throttle to adjust the position of the throttle to keep the desired speed constant.12

Chrysler was the first to market the system, which was variously known as Speedostat or Auto-Pilot (foreshadowing Tesla’s name for their semiautonomous driving system), and later Chrysler came up with the name “Cruise Control,” which eventually stuck.

The cruise control innovation is important because this was the first taste most drivers had of any sort of actual driving automation. Sure, automatic transmissions—and before that, automatic spark advance and oiling and so on—took over many of the functions of the operation of a car that used to be manual, but those, including gear shifting, were less about the actual piloting of the vehicle itself and more about the technical requirements needed to get the car to drive at all.

Cruise control, though, was clearly different, in that it took one of the primary tasks of driving—speed control—away from the human driver and placed it under control of the machine. Sure, this was the simplest form of control, with no ability to independently sense its environment, but it was a start. Modern dynamic-cruise systems use radar to keep a set distance away from the car in front, and can brake automatically if the system determines it’s approaching an object in front of it too rapidly.

All of this is thanks to one blind man and his lawyer—who couldn’t drive and talk at the same time.