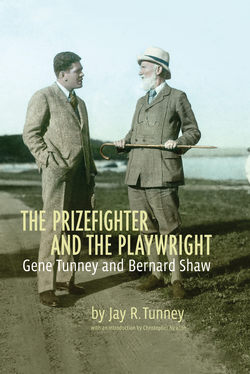

Читать книгу The Prizefighter and the Playwright - Jay R. Tunney - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

Big Sissy Reads

“There is little to suggest the gladiator in this mild, quiet-spoken, blue-eyed individual as he talks of tennis, golf, books — Wells, Tennyson and Omar Khayam are among his favorite authors.”

BRIAN BELL, REPORTER

Brian Bell didn’t know he was going to change someone’s life when he drove up to the Adirondacks, the most northerly place he’d ever been in New York or any other state. He was just glad to get out of New York City and away from the desk on a sweltering summer day. Bell had covered news stories since he was in knee pants, when, at age ten, he mailed clips to The State, the largest newspaper in his native South Carolina. Later, he had covered the Scopes “Monkey” Trial — in fact, had broken so many scoops on that trial that he had become something of a legend in the news business. Today was a new assignment, however, and his first sports assignment for the Associated Press.

On this summer day in 1926, Bell was en route to visit Gene Tunney, “The Fighting Marine” from Greenwich Village who was training to battle Jack Dempsey for the world heavyweight championship, the biggest prize in sports. No one knew much about Tunney, a city boy from a poor Irish family whose background reflected the changing demographics of a country moving toward urbanization. At 29, Tunney had fought 74 professional fights and lost only once, to Harry Greb, “the Pittsburgh Windmill.” It was a fight so murderous that viewers at ringside were splattered in red, Greb’s gloves were soggy, and the canvas was soaked in Tunney’s blood. The fighter-Marine defeated Greb three times in return bouts and fought him once to a draw.

“Just go up to Tunney’s training camp and look around for the usual stuff and give it a feature touch, for the most part,” said his boss and good friend, Alan Gould, the wire service’s sports editor. “Get a little something of the personality.” It didn’t matter, said Gould, that Bell had never been to a training camp and had never met the boxer; Bell was one of the best feature writers in the business, and he’d know what to do when he got there.

In the summer of 1926, there was no better job for a reporter than covering sports. The appetite of the nation’s newspapers for sports news had quadrupled since the Great War. The readers’ thirst for the minutest details of every aspect of a celebrity’s life was insatiable, and sports fans knew more about their heroes than they knew about members of their own families. Personal magnetism, charisma, youthful vitality and the will to win, also the hallmarks of a growing business culture, became imperative in sports. Millions of spectators were crowding into stadiums and onto golf courses, and sports champions became heroes overnight: Bobby Jones in golf, Bill Tilden in tennis, Babe Ruth in baseball, Red Grange in football, Earle Sande in horse racing. In the era called the Golden Age of Sports, boxing was king, drawing the most in money and spectators. Jack Dempsey made more money in one fight than Babe Ruth earned in a year, and he had twice defended his title as heavyweight champion in million-dollar gates. An estimated 12 million Americans watched boxing matches or fought in neighborhood gyms and athletic contests. Reporters vied for scoops, and major newspapers featured columnists with colorful prose meant to sway and titillate the public, as well as sell newspapers.

In London, even the playwright Bernard Shaw occasionally wrote columns on sports, sometimes taking aim at sportswriters themselves. “The time is evidently very near when journalists will have to obtain certificates of competence, like navigating officers, before they are allowed to navigate the ship of state and hypnotize and psycho-analyze the helpless public by their pens,” he wrote. “I hope they will be examined just as strictly in pugilism as in political economy when that time comes.” At one point he was so fed up with what he felt was inept coverage of boxing that he suggested, somewhat in jest, that a bill be introduced “making it a punishable offence for a newspaper to order or publish any description of a prizefight until they had sent for a professional boxer and made the writer spar a bye with him, and obtain from a couple of competent judges a certificate that he at least knows his right hand from his left.”

Bell found Tunney’s training camp alongside a placid, pine-rimmed lake called, appropriately enough, Lake Pleasant, just off a two-lane highway that wove through the mountain resort village of Speculator, New York. The Osborne Inn, a sprawling, three-story white-shingled hotel with a wide verandah facing the lake, was run by one of Tunney’s Marine buddies and served as headquarters for the press, with rooms, gossip, a well-stocked bar, a telephone and a menu boasting the “best apple pie north of Manhattan.”

Outside, only a few steps from the inn, an elevated platform resembling a large open porch served as the training ring. It was roofed to protect it from sun and rain, and open on the sides so that spectators could sit in the grass, on the newly erected pine bleachers or on the tops of cars to see workouts and match wits with the experts on whether the challenger could beat the champ. Not many thought Tunney had a chance. Dempsey had been heavyweight champion for seven years, and reporters writing daily stories from the opposing training camps had almost unanimously picked Dempsey as invincible.

As Bell later recounted, it seemed a little like going to a farm auction and looking over the stock. He arrived too late in the day to schedule an interview, so with ring workouts completed, he jammed a notebook in his pocket and went off to where he was told he might find the target of his story. He tromped along the shoreline and into the trees until he spotted what he called a “secret cabin.”

On receiving no answer to his knock, he opened the door and slipped inside. What he saw surprised him for its almost monastic orderliness. There was a neatly made-up single cot, a camp desk with a portable typewriter, a wood chair, a dresser and shelves neatly lined with row upon row of books. Good grief, he thought. One might think that the occupant was a college student or an author. It was hardly the kind of space one would expect for a boxer, not that Bell knew any boxers, but he could tell from the training paraphernalia that it was undoubtedly Tunney’s living quarters. Bell sat down in the chair and picked up a book.

As one of nine living in a cramped New York apartment, Gene had found seclusion on the Hudson River docks. Those early memories and a driving need for personal space had made him insist, against the advice of his manager and trainers, that he have a private sanctuary at Speculator. His rough-hewed clapboard cabin, known as “the shack” to reporters, was off-limits to visitors. Jogging back late in the day from an hour’s run, Gene was troubled to see the silhouette of someone inside. He opened the door, ready to unleash his anger at the intruder.

Bell was only a few years older than Tunney, a big, burly, Scotch-Irish American with the ability, said friends, to charm anyone’s socks off. The reporter instinctively saw that his presence was unappreciated. Without trying to make excuses, Bell simply apologized, saying that he had hoped to get acquainted and would like an interview. Then, looking toward the stack of books on the night table, Bell smiled and asked, “What are you reading?”

Gene’s concern about a visitor vanished. He was enormously pleased that someone was asking about authors instead of his punches, knockdowns, right cross and brittle knuckles. It was a relief to be invited to talk to a reporter about books and ideas, subjects that were infinitely more interesting to him than talking about the upcoming fight. Gene sat down on the bed and gestured for Bell to use the chair.

“Reading now? The Way of All Flesh,” replied Gene, “an autobiographical novel by Samuel Butler.” He went on to say that the book had an excellent preface by George Bernard Shaw who praised it as a neglected masterpiece. In fact, Tunney said he had bought it at a used book store for 50 cents during a trip to Los Angeles, specifically because he noticed the preface was written by Shaw, the world-famous playwright who had won the Nobel Prize for literature and was an author he admired for his wit and wisdom.

As if to cap off the conversation, Tunney said he found the book’s lessons on an English cleric’s self-righteous use of religion to manipulate his son to be absorbing and the discussions of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species thought-provoking. In questioning the pretentious social class values of Victorian society, he said, Butler, like Shaw, offered hope for the freedom of the individual against hypocritical conventions.

Bell was nonplussed. He took out a new notebook, resettled himself in the chair and prepared to interview this “man of multiple surprises,” a man with wide-ranging interests and a command of language who was so filled with energy that he seemed to gesticulate constantly. Often getting up to pull out a book, he spoke faster than Bell could take notes. Tunney had a quick wit and enjoyed repartee, and Bell found him a willing audience for his own humorous tales about the newspaper business and his southern family.

There had been snickering about Tunney’s habit of reading during training and of using multi-syllable words. “Most prizefighters talk in words of one syllable and sharpen their jackknives on the backs of their necks,” said a Newspaper Enterprise Association syndicated story about Gene written the year before. When Gene said he liked poetry, the surprised interviewer said he “clung to his chair and took a shot from his pocket flask of aromatic spirits of ammonia to steady himself.” The article was published in the Chicago Post, with the headline “The Boxing Savant.” At the time, Tunney was not yet signed to fight Dempsey and the tale of the heavyweight who read poetry was dismissed as laughable.

In general, the sportswriters didn’t really care about Tunney’s inner life, about what he read, why he read or what he thought. They didn’t care that he walked to church, read the editorial pages of newspapers, including The New York Times, that he was a member of the Shakespearean Society or that he had memorized Hamlet. If anything, they were irritated that his reading habit made him less accessible because it consumed his time away from the ring. Reading skills weren’t why Tunney was in the limelight. Tunney hadn’t graduated from high school, and his ability, or inability, to decipher a sentence and expand his vocabulary appeared to have no bearing whatsoever on whether he could withstand the crushing onslaughts of “The Manassa Mauler.”

Books on the shelves of Tunney’s cabin included a leather-bound set of the complete plays of William Shakespeare, novels by H.G. Wells, Thomas Hardy, Jack London, Victor Hugo, Thornton Wilder’s The Cabala, the poetry of Percy Shelley and W.B. Yeats, a Bible, Jeffrey Farnol’s The Amateur Gentleman and The Broad Highway, and Bernard Shaw’s Cashel Byron’s Profession, and plays including Back to Methuselah, Saint Joan, and Pygmalion. Gene said he had read them all at least once, sometimes several times. “I am always deliberate and methodical, my normal gait for most things,” said Gene. “I could never just skim a book and I always appreciate the mes-sage more in the rereading.”

Bell knew at once that he was onto a bigger and better story than the usual feature about a heavyweight contender hitting speed bags. The contradiction of a boxer reading literature would capture headlines and grab attention. As an experienced newsman who appreciated literature, Bell was also well-equipped to play the role that every newspaper writer hopes to have: that of being the first to develop and elaborate on a major story — a scoop. The Associated Press was the largest general news agency in the world, which made it uniquely suited to sending stories to a far-flung audience.

Several days later, Bell’s story on the fighter who loved to read was distributed to virtually every newspaper in the country and to papers overseas. Bell’s boss, Alan Gould, said that other sportswriters, suspecting a clever publicity gimmick drummed up to get coverage, initially ignored the report. When they learned it was true, the regulars were irritated to be scooped by a reporter who wasn’t even a regular on the beat. Editors clamored for follow-up details. Almost overnight, the story ballooned and the massive maw of the sports press took over, making the tale of Gene’s reading a bigger yarn than Rip Van Winkle.

Initially, Gene was elated with the attention the news created. He was pleased and proud to finally be seen as someone distinct from Dempsey, someone smart and a man with more to offer than a boxer’s biceps. It made him feel good to be recognized as a reader of fine literature. As if to emphasize his new status, he stashed books in his gear and started carrying volumes around the training camp. Visitors said that at meals, he often dropped a book or two on the table. Gene, still unknown to those who didn’t follow sports and impressed simply to see his name spelled correctly, was unaccustomed to being in the headlines. He lacked any understanding of how to cope with the intense publicity brought to bear on public figures during the prosperous post-war era of the Roaring Twenties. He was totally unprepared for celebrity. In the language of the idiom, he was wet behind the ears.

Indeed, one of Gene’s greatest strengths — his ability to focus and block out all surroundings — became his biggest weakness outside the ring. The concentration and willpower that enabled him to drive himself almost beyond endurance to utilize his mental and physical powers in pursuit of the championship also made it easier for him to disregard what seemed irrelevant remarks that reporters and the boxing crowd might be saying about him.

“It never occurred to me,” he said, “that a habit of reading could be seen as a stunt or a joke. Wasn’t reading something we wanted to champion?” He had no inkling of how absurd the notion of a literate prizefighter might seem to the sportswriters. Nor did he appreciate the day-to-day need for competing columnists to write controversial, provocative, even negative, copy to sell newspapers.

Until Bell’s story, sportswriters had considered the man challenging Dempsey for the championship to be a boring, colorless figure who kept to himself. Most sports celebrities were easy to write about because they tended toward extravagances with women, gambling, alcohol, temper tantrums, problems with their managers, with money, or tangles with the law.

“The average pug, when he lets down, gets roaring drunk or takes to sitting up all night pounding night-club tables with little wooden mallets, reaching hungrily for the powdered nakedness of the girls who march by,” wrote sportswriter Paul Gallico.

Tunney didn’t hang around with writers or other visitors playing card games or drinking beer, common pursuits in a training camp that also allowed reporters to know the sports figure better. Instead he spent the five hours between his morning and afternoon workouts reading, and the evenings listening to classical music.

In contrast, “the old Dempsey camps were magnificent social cross-sections of vulgarity and brutality,” wrote Gallico. “Phonographs brayed, spar mates brawled, the champ played pinochle or roughhoused, frowsy blondes got themselves into the pictures at nighttime.”

Tunney had been a difficult and enigmatic personality to capture on paper and was, in effect, a nonentity. Bell’s scoop and all the incredulous stories that followed were dreams come true for reporters, most of whom considered a heavyweight boxer reading books a spoof, as hilarious as a presidential candidate singing arias. It was a story that eventually moved from sports pages to front pages, catching the attention of the general public and incidentally making boxers more interesting to people, including women, who didn’t normally follow the sport.

Columnists and comedians picked up the drumbeat that Tunney, the challenger to the heavyweight boxing title, was training to beat the “man-killer” Dempsey on a diet of classical authors. Sportswriters and broadcasters spouted witty remarks about the “Bard of Biff” and “Genteel Gene,” sure that no serious contender would read novels and plays, much less poetry, while training for the most important fight of his career.

“In Gene Tunney, pugilism has found a Galahad far more taxing to credulity than novelist, playwright or scenarist would dare to conceive,” wrote Ed Van Every of the New York Evening World.

Once he realized he was being made a laughingstock, Gene agonized over it, worrying that he was too sensitive yet unable to put it behind him. In telling the truth, in trying to be himself, he had been held up to ridicule. In trying to fix it, he made it worse, and the perception of Gene as impersonal and arrogant took root. From childhood, he had never backed down from confrontation, and his experience at verbal encounters had been finely honed at the family dinner table. He tried to talk his way out of it, but his explanations often engendered disbelief.

“Some think I am high-hatting the boys when I talk about literature. I am not,” Gene said defensively. “It is a hobby with me, just as Jem Mace, a bare-knuckle champion of the 1860s, played the violin, and Jem Ward, another prize-ring title holder, painted pictures.” Jem Mace? Playing the violin? Few had ever heard of him.

It also didn’t help that he had what some called “an oddly British quality” to his speech, especially in public, making him sound pretentious. Gene did not explain that his father had a bit of a British accent, that Aunt Margaret routinely quoted Shakespeare, and that his brother Tom, now a policeman, couldn’t get through a dinner without reciting Edgar Allan Poe and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

“The kid from Greenwich talked like a gentleman from Mayfair,” said columnist Ed Fitzgerald. He had “a most unpugilistic interest in things like art, science, music and literature, and he never used a short word if he could think of a big one instead.”

One author wrote that “Tunney’s affected convoluted speech patterns were as foreign to most Americans as an untranslated poem by Baudelaire.”

“Actually,” said Gene, shifting the blame, “some visitors, seeing me reading in my spare moments, had a little fun in their conversations with me by using big words.” There was perhaps nothing more likely to raise Gene’s ire than the feeling that others were making a fool of him. Instead of bluntly telling someone off, however, Gene was always more likely to bury his feelings, keep a straight face and resort to wordplay to diminish his adversary. This paradoxical Irish propensity for purposely using big words in conversations was misunderstood by reporters and many readers.

“Taking up the joke, I answered back in polysyllables. I’m afraid,” he said, in a supreme understatement, “some of the innocent bystanders took me seriously and thought I was parading my knowledge.”

He blamed himself, thinking he should have been less cocky, shown more patience, seen a backlash coming and understood that his popularity with the fans might ultimately be affected. “Along came this new guy, Tunney, who makes it clear he’s an intellectual, or pretends to be, and the writers took whacks at him — they hated him, so we hated him,” recalled author Studs Terkel, who was a boy at the time. “Dempsey was never much interested in reading, writing and learning, but he was a scrapper, a mauler! No one on our block liked Tunney, except my older brother, an academic. Everyone wanted Tunney to lose.”

For Gene, books became ever more an escape, an Alice in Wonderland tumble into world after world after world, providing lyrical language and peaceful landscapes far removed from the fight game. Words and stories were a form of meditation, allowing him to relieve tension and stress. Reading became central to his ability to concentrate and focus, making books invaluable tools of training.

He had always felt that the art of repose was one of a boxer’s major challenges. In quiet desperation in the weeks before an important bout, many prizefighters filled spare time with hangers-on, sycophants, idle talk and the rowdy, barlike atmosphere in training camps to try to calm their jangled nerves. A boxer tended to be nervous and jumpy and could easily wear himself down through anticipation and lack of rest. Even in the ring, fighting itself came in flurries. For a large part of the time a boxer was sparring, not hitting, and the less nervous energy he burned and the more relaxed he kept his body, the better he fought.

Gene said that books helped him understand who he was and where he wanted to go and gave him the discipline to distance himself from his work. In the ring, a rested mind allowed him to strategize. “The truth is, I became addicted to reading not in spite of pugilism, but largely because of it,” he recalled. “For me, fisticuffs and literature were allied arts, through the medium of training.” The explanation was largely dismissed by the unsympathetic fight crowd. But not by Greb.

Harry Greb, one of Dempsey’s toughest sparring partners, the only man who ever beat Tunney in the ring, and a boxer who exemplified the physical and brutal life of a prizefighter, took the story of reading seriously.

“Gene reads books? Did you know that?” Greb asked sportswriter James R. Fair.

“Do you think he gets anything out of them?” asked Fair.

“Why, Jim,” Greb asked in amazement, “Do you think he don’t? When he reads a book, I’ll bet my last dollar he knows as much about it as the man who wrote it does. And I’ll tell you why. I gave him a lesson in our first fight and he learned it so well that I was never able to hurt him or cut him up again. I don’t know why he reads them, but by God he knows what he’s reading.” Greb was one of the few in boxing circles who predicted Tunney would beat Dempsey, but his opinion was ignored.

Tunney was fighting for a life beyond the ring. He was fighting to be “the respectable gentleman” that his mother idolized. He wanted to put the tedious, repetitious work of the dock clerk behind him, along with the sameness of daily living and a paycheck too big to leave him poor but too small to allow him his dreams. In the doctor’s waiting room, he had read about poor boys that had triumphed. As a teenager, he had bought standing-room-only tickets for the Metropolitan Opera to hear the most famous singer of the era, Enrico Caruso. Watching alone from the back of the house, he had been as entranced by the social elite passing down the aisles as he had been by the extraordinary power of Caruso’s voice. Outside, he remembered huddling in the cold from across a snowy street as men in top hats and white ties and women in long gowns stepped from carriages and chauffer-driven luxury sedans.

Nor had he forgotten that as a schoolboy he had practiced for marathons by racing buses up Fifth Avenue, past grand mansions, apartment houses with doormen in livery, and stores with opulent window displays of clothing, furs and jewelry.

In time, through wealthy friends and backers, Tunney had been introduced to a society where words commanded respect, households had cooks and butlers, homes were big enough to have libraries and gaming rooms, and manicured lawns and formal dinners were commonplace. “I had a 33-room house, a staff, an elevator to the third floor, a butler, and all the things that go with it. He liked that house,” said his close friend Samuel F. Pryor, the son of a wealthy gun manufacturer, whom he had met on a troopship returning home from Europe. “He liked to come and stay.”

Tunney had been invited to spar at the private and prestigious New York Athletic Club and the City Athletic Club with millionaires and businessmen who lived not in one house but two or three and who vacationed in Florida and Europe. Gene liked that style of living, and he was not going to give up his pursuit of a better life because the press had a different idea of how a boxer should live. In his striving, he did not realize that in rejecting the expectations of the fight crowd, he was also turning his back on their attitudes and values. Many of them were not educated, could not read, never wanted any other life but to be on the fringes of the sport and interpreted Gene’s desire for something more as a personal affront. He was separating himself from those whose support he needed to be popular.

Seize opportunities, Gene always said, quoting Shakespeare: “I have wasted time, and now doth time waste me.”

“Seizing opportunities reveals the kind of stuff we are made of. Men do not lack opportunities,” he said, “they miss them.” Learning and reading, he said, were the stepping-stones to opportunity.

In interviews, Gene irritated sportswriters by talking about boxing dispassionately as a science, as a job, discussing musculature and bone structure. He analyzed fighters as if he were an engineer not as a battle-tested pug.

“You know, I always fight my battles out beforehand,” he said. “I mean by that, I plan and live through them by myself, figuring out my opponents and my own attack and defense.”

He studied fight films for hours as he studied books, watching them over and over again. He hired boxers who had fought his opponents as sparring partners. He drew detailed diagrams of the body’s vital points, and as a spectator at bouts sat in a seat near the ring drawing diagrams with a pencil and feverishly taking notes on the action. He relied on Wilburn Pardon Bower’s Applied Anatomy and Kinesiology and probably read more medical books than any boxer in history.

“I think of pugilism as a fencing bout of gloved fists, rather than an act of assault and battery,” he said. “You’ve got to cultivate the art of thinking as expressed in action.”

It reached the point that whatever Gene said seemed alien to the traditional boxing crowd, and in print, the words tasted hypocritical. “Call me a boxer, a pugilist,” he said repeatedly, “not a fighter.” Not a fighter? A heavyweight contender training for a championship fight? Who was he kidding? they asked.

“As defined in the dictionary,” he said, “the word ‘fight’ connotes a hostile encounter, and there’s no room in a boxing contest for hostility.” (He always maintained this distinction; he was pleased to say he had been a professional prizefighter who engaged in boxing, but that he never “fought.”)

A year later, he arrived in Chicago and noted there was talk “about some fight to be held.” He said he knew nothing about it. “I am here to train for a boxing contest, not a fight. I don’t like fighting. Never did. But I’m free to admit that I like boxing.”

As for the hangers-on who infested the boxing world of the 1920s, Gene had no time for them either. Having grown up in a neighborhood with gangs, he saw no reason why he should tolerate riffraff, bootleggers, two-timing politicians, second-rate managers, roughnecks and criminals. He saw boxing as a profession, much like being a dentist, except that the career was shorter. The rewards were great if one was good enough. Gene was convinced he had trained himself to be not only good but the best, and he confidently told anyone willing to listen that he was ready for Dempsey.

“I shall be champion,” he told the British poet Robert Nichols during an interview. “Yes, it’s written in the stars that I shall be champion. When I have won — and I shall win,” Gene told Nichols, “I want to become a cultivated person.” Nichols was one of many non-sportswriters assigned to interview Tunney, to try to determine if he was a fake and whether he actually knew and could correctly quote literature as he claimed.

“Tunney speaks better English than most Englishmen,” noted Nichols. “His sentences do not trail off into sheer vagueness.” Nichols said the articulate Tunney told him that by cultivated, he meant “a man who has some acquaintance with what man has seen and felt, and uses this acquaintance to understand the present world around him.”

When Maine author and writer Roger Batchelder met Tunney, he wrote that he “inquired rather furtively about the pugilist’s familiarity with the works of the Bard.” As they sat together at luncheon, “My host recited the advice of Polonius to Laertes in a soft rhythm that seemed strange from one of such massive frame.” Tunney’s big fingers drummed on the table as though to continue the cadence of Shakespeare’s rhythm as he quoted these words:

Neither a borrower nor a lender be,

For loan oft loses both itself and friend,

And borrowing dulleth the edge of husbandry.

This above all, to thine own self be true,

And it must follow as the night the day,

Thou canst not then be false to any man.

Before the luncheon was over, Tunney had discussed Dempsey, boxing, his school days, politics, “some sort of ‘ology’ which gave him complete knowledge of the muscles of the body, their means of functioning, and the results of an onslaught on the defensive muscles.” And he had quoted much more Shakespeare, including the soliloquy of Henry IV on sleep, many passages from The Merchant of Venice and others, “all effective, well done.”

“He speaks easily in fluent English, unlike many of his comrades in the ring,” wrote Batchelder. “His poise is absolute, where Dempsey in previous interviews with the writer has often fidgeted, and grasped for words which might enable him best to express himself.”

Tunney told him he did not start the ballyhoo in the press, “for I should hate to have any of my followers think that I’m a pseudo-highbrow. Shakespeare,” he said, “offers me infinite relaxation, and since that is essential in my business, I turn to him for assistance, as well as for my own enjoyment.”

The interview undoubtedly raised the spirits of English teachers everywhere, but did little to help Tunney with his core constituency.

A Chicago policeman named Mike Trant, a self-appointed bodyguard for Dempsey, investigated the peculiar literary goings-on at the Speculator training camp and eagerly took his findings back to the champion.

“The fight’s in the bag, Jack,” he gloated. “The so-and-so is up there reading a book. A big sissy!” Dempsey believed it. Dempsey’s supporters repeated stories that Tunney had no punch, that he was a synthetic fighter, not a natural one, and that he didn’t have the killer instinct that fans considered mandatory to win in the ring. Most importantly, he didn’t look or act like a fighter. Now, there were books to go along with the looks.

President Calvin Coolidge would say that Tunney “looked more like a movie actor than a prizefighter.” Cornelius J. Vanderbilt, Jr. called him a “perfect Adonis.” One columnist said he could be a “young ascetic priest.” No one said he looked or acted like a fighter.

“Dempsey fights with the killer spirit,” said The Baltimore Sun, characterizing the champion as did Bernard Shaw. “He is entirely reckless. He doesn’t care what happens to anybody, himself or the other fellow. It is easy to imagine Dempsey in an earlier age fighting the desperate combats of the caveman.” Tunney, on the other hand, had the head of a student. “Tunney might be a scientist, a physician, a lawyer, an engineer, if he had been given a chance to study instead of going to work when he was still a boy.”

When Grantland Rice, the kindly dean of the boxing writers, arrived at Gene’s training camp in the Adirondacks with syndicated columnist Ring Lardner, an ardent Dempsey backer, they ran into the boxer carrying a fat book under one arm. “He could have passed for a young college athlete studying for his master’s in English,” said Rice.

“What’s the title?” asked Lardner, who looked at Tunney in contempt.

“The Rubaiyat,” replied a smiling Tunney, holding up a translation by Edward Fitzgerald. Then gesturing toward the mountains, the boxer added that the setting was so beautiful he had hardly been able to take his eyes off the scenery.

Lardner fixed Tunney with steely eyes. “Then why the book?”

Paul Gallico of the New York Daily News, an influential skeptic, mirrored, as well as stimulated, the sentiment of the majority:

I think Tunney has hurt his own game with his cultural nonsense. It is a fine thing that he has educated himself to the point where he no longer says dese and dem and dose, and where he can alone tell one bookfrom another, but also indicate some familiarity with their contents, but his publicity has built him up as a scholar more than a fighter, and the man who steps into the ring with Dempsey with nothing but his hands as weapons needs to be a fighter and nothing else but. He will have to have a natural viciousness and nastiness well up in him that will transcend rules and reason, that will make him want to fight foul if he thinks he can get away with it, that will make him want to commit murder with his two hands. And I don’t think that Master Tunney, who likes first editions and rare paintings and works of art, has it in him.

At night, alone in his cabin, Gene paced and began to imagine his fate might match that of Shakespeare’s protagonist in The Tragedy of Coriolanus. Coriolanus was the fifth-century Roman military hero who thought that bravery was in one’s heart and actions and that a man should be recognized on his own merits. While campaigning for the Roman Senate, he ignored the public, who wanted him to trumpet his military accomplishments and actively seek their support. Coriolanus had too much pride and felt demeaned by the political process, just as Gene was prideful and felt demeaned by the press. Coriolanus was assassinated.

“It was no spiritual gratification to know that I was an unpopular champion,” he said. “It made me resentful of the very idea of popularity. I developed a sense of perverse amusement in the game of living precisely as I wanted to and damn anyone else’s opinion.” He stopped reading the sports news and focused only on training, taking long jogs alone and sometimes issuing statements instead of holding press conferences. He was confident that once he became champion, people would admire him.

In dark hours, he grieved over his younger brother and best friend, John, a thoughtful man destined for the priesthood who had always taken his side in household disputes with their difficult and demanding father.

He remembered as if it were yesterday arriving home from Europe, still proudly wearing his uniform, and striding into the small apartment on a sunny August afternoon laughing and bearing gifts. He was the first in his family to travel in Europe, and he was full of boyish wonder, of stories of Paris and the Champs-Elysées and Eiffel Tower, of sailing up the Rhine, of taking up boxing to avoid guarding empty balloon sheds and his triumph as “The Fighting Marine” who won the a.e.f. championship before an audience of dignitaries from the American, French and Belgian governments, including Prince Albert and General John J. Pershing.

Suddenly, he stopped talking. In the pregnant hush, he looked from face to face, and it took but a moment for him to realize one person was missing.

“John? Where’s John?” he asked.

No one moved. No one said anything. No one knew what to say. Agnes, the youngest, hid behind her older sisters so she wouldn’t have to watch his face. Tom bowed his head and studied the plain wood floor as if he had never seen it before. The family stood there in the parlor of the small walk-up apartment in tense silence, the only sounds the traffic and bleating from vegetable vendors on the streets below. Their eyes were lowered in a tableau of unspoken meaning.

“It was a terrible moment,” remembered Agnes. “No one knew how to tell him.” No one could find the words to explain the unexplainable. John, always the good Samaritan, the only one who could rally the family’s spirits when Papa’s abuse had spilled over, had been killed — murdered, the family said — at a local club. Police said he had come to the defense of a girl whose name he never knew against a drunken bully who tossed cigarette ashes on her dress. John was shot in the head and died in a hospital two days later.

Heartsick, Gene dropped the gifts, turned, left the apartment without speaking and walked for hours through the city. He returned to the docks to sit alone through a long night, blaming himself for not being by John’s side, chastising himself for celebrating a boxing victory in Paris while his closest friend and soul mate lay dying.

Sometimes, he thought of his father. The sarcastic and unforgiving Red had died in April 1923 of an aneurysm, his prized union card under his pillow. He had never offered encouragement to his eldest son, never acknowledged reading newspaper coverage of his son’s ring battles, and he never saw Gene in a professional fight. He died without either of them resolving their lifelong animosity. Gene felt a sadness of lost opportunity that he would never be able to put into words. For the rest of his life, he would rarely speak of his father or his beloved brother John again.

Lying on his bunk in his small wood cabin in the Adirondacks, Gene had time to think. He wished for a trusted mentor in whom he could confide, whom he could talk to about his fears and concerns, his dreams for the future. On the brink of preparing for the biggest fight of his life, surrounded by dozens of supporters and ever more a public figure, he felt increasingly isolated and was sometimes desperately lonely.

Bell’s article and those that followed exposed his most private yearnings to public ridicule, and despite the assurance of friends, he struggled to understand why he should be shamed for trying to better himself. Books had made him an outsider in his profession at the very moment he was reaching for the crown jewel of sport, the heavyweight championship. He saw winning as the only way out, the only way to prove himself. He thought that once he had won, the public’s failure to understand him would pass, and he would be accepted by the boxing crowd for the man he was. He felt he had to slay the dragon to get ahead, and the dragon was Dempsey. “Think it, practice it, do it” became his mantra.

He also turned to prayer, believing that his faith would give him strength. He had grown up so devout that at age 21, he felt sinful that he hid his rosary in his bunk instead of kneeling beside his bed in front of other Marines to pray. He bent his knees at more altar rails than his friends would have known about, but he harbored questions about original sin for which he was ashamed and thought there were no answers.

“He was troubled, but he was truly a very good person,” said his friend Sam Pryor.

On days off in Speculator, and sometimes late into the night, he visited Father John Murnane, a Franciscan priest, to discuss God and man and Gene’s favorite saint, Saint Francis of Assisi. Saint Francis was a troubadour who captured for Christianity the joy in nature, the love for the sun and the moon, the trees, the clouds, the flowers and the birds, a saint who felt happiness did not come from comfort or material possessions but from serving others. When Gene sat outside alone under the night sky or walked along pine-covered mountain paths, he felt nature was God’s cathedral and that he could speak to God directly. Catholic priests were friends and frequent visitors to his camp, and in talking with them, he struggled inwardly with bridging the gap between rigid church doctrine and his own independent thinking. These were not thoughts that he dared talk about with the clergy or his fervently religious family.

Bernard Shaw had shown him a way out.

Gene had seen Shaw’s play Saint Joan, which had its world premiere in New York in 1923, and he had been profoundly moved by the story of the warrior saint, an ignorant peasant girl of unparalleled vision and courage who led the French army to victory in battles against the English and then was accused of heresy and burned at the stake by the dominant Roman Catholic Church. Joan’s alleged blasphemy was listening to what she felt were God’s wishes spoken to her through the voices of her angels rather than through obeying the Church’s interpretation of God’s will. Gene was touched by Joan’s plain-spoken individual conscience.

Shaw had written that Joan’s lesson was, “Though He slay me, yet will I trust in Him; but I will maintain my own ways before Him.” The playwright, whose philosophy of religion did not mesh with traditional Christian teachings, felt the church should accept the freethinker as well as the faithful if it were to maintain authority with a modern congregation. Shaw felt that men of reason and science must be embraced by the church and that the true Christian Church was both Roman Catholic and Protestant in one. He wrote in his preface to the play that Joan’s burning at the stake in 1431 made her the first Protestant martyr.

Gene found the play deeply provocative. After reading it, he changed from a doctrinaire Catholic to one who adhered to faith in God as the Creator of all things but who maintained his own conscience and responsibility for moral decisions, without needing his priest as he had as a child. He found comfort in memorizing much of Saint Joan, repeating the words during hours of jogging through the Adirondacks:

To shut me from the light of the sky and the sight of the fields and flowers; to chain my feet so that I can never again ride with the soldiers nor climb the hills; to make me breathe foul damp darkness, and keep from me everything that brings me back to the love of God when your wickedness and foolishness tempt me to hate Him...if only I could still hear the wind in the trees, the larks in the sunshine, the young lambs crying through the healthy frost, and the blessed blessed church bells that send my angel voices floating to me on the wind. But without these things, I cannot live.

Gene told friends that Shaw’s preface to the play was one of the finest pieces of writing he’d ever read and that it “ought to have him canonized in a century or two.” Shaw felt that Catholicism was not yet catholic enough and Gene agreed. In later years he would name his only daughter, Joan.

In London, Shaw was following daily news reports of the buildup for the fight between Tunney and Dempsey. For the first time since 1924, when he had seen in the newsreels the battle in which Tunney had defeated the French champion, Georges Carpentier, Shaw was excited about a championship bout. Everything he remembered and read about Tunney interested him, in no small part because the boxer seemed to bear a resemblance to his fictional hero Cashel Byron, and Tunney was fighting against a man who was the personification of Cashel’s fictional opponent, the mauler Billy Paradise. Shaw told Lawrence Langner, his exclusive agent in New York, that the invincible Dempsey could be beaten by a scientific fighter.

Wait and see, he told Langner.

Late in the day on September 23, 1926, with his manager, trainers, and friends hovering near, Tunney closed himself in his room, and with only hours to go before doing battle for the championship, finished rereading for the fourth time the book that Shaw held up as a masterpiece, Samuel Butler’s The Way of All Flesh. The day of the fight, nearly every sportswriter in the country predicted he would lose, and they continued to question whether reading was a suitable preoccupation for someone in his profession. The Chicago Daily Tribune was almost kindly:

Mr. Tunney, the refined prizefighter who will endeavor to smear Mr. Dempsey’s paraffin nose all over his (Mr. Dempsey’s) features, is reading Samuel Butler’s The Way of All Flesh. Mr. Dempsey confines his reading to the comic strips, his trainer reading the two-syllable words aloud to him. We applaud Mr. Tunney’s love of great literature as greatly as we deplore Mr. Dempsey’s indifference to the words of the master minds. However, and after all, the two gentlemen are to meet in a fistic combat and not in a competitive examination on English literature.

The air was thick with moisture, and the rain, which would soon turn into a torrential downpour, had not yet started when Gene pushed aside the top rope, pulled the blue robe with the U.S. Marine emblem tightly around him, and climbed into the ring at Philadelphia’s new Sesquicentennial Stadium. There were tens of thousands of spectators, enough to fill a mid-sized American city, and more than 400 reporters. The cheapest seats were so far away that fans sitting in them had brought binoculars to see the ring.

Bob Edgren, whose drawings and columns had been Gene’s introduction to reading and boxing, was at ringside with colleagues from the New York Evening World. In the first row, on a pine bench so close to the ring he could touch it, wearing a fedora to shield his eyes from the glare of the powerful arc lights, was the reporter who had first written the story on Gene’s reading habits, the affable Brian Bell. He had asked Gene to be godfather to his son, born only the day before. Bell told his colleagues that he predicted Tunney would win. “Ha!” said ap’s Charlie Dunkley, also sitting at ringside. “Why, the so-and-so can barely punch holes in a lace curtain!”

Gene caught Bell’s eye, and smiled.

Philadelphia, September 23, 1926.