Читать книгу The Prizefighter and the Playwright - Jay R. Tunney - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

So perhaps this is what he was really like. It’s clear from Holroyd and all the other biographers that Shaw was a generous man. He was more than kind to Wilde when he was in trouble. He gave anonymously to so many good causes and to so many people who were hurt or sick or caught in circumstances over which they had no control, but to me the public voice always seemed unsympathetic, hectoring and dissatisfied. I have a fading memory of hearing Shaw on the radio when I was eleven or twelve. Because he was a famous, even revered, celebrity, my parents encouraged me to listen. Unfortunately my memory is of a voice complaining endlessly about something which didn’t interest me.

Even the plays weren’t particularly compelling. It was perhaps 1950 when I saw an amateur production of Pygmalion — a play by the great Bernard Shaw! Already fascinated by the theatre, by make believe, I needed to see this play which was done in modern dress by local amateurs. But there were too many words and I suspect that I was more intrigued by hearing someone use a swear word on stage than anything else. That was thrilling, but the rest paled in comparison and I gained an impression that I carried with me for years that his plays were simply animated lectures. And in this, of course, I was not alone.

My very first professional job — acting in Saint Joan and Julius Caesar with the Canadian Players — didn’t change my mind. I was happy to be acting. I was happy to see all of Canada from Port aux Basques to Trail but on stage it was Julius Caesar that intrigued me not Saint Joan. I played at the Shaw Festival in the early days and again I thought I’d been caught up in a lecture not a real play, not an adventure that connected the audience with the stage. I played Henry Higgins with Nicola Cavendish in Vancouver but wasn’t convinced. It was not until I first directed Shaw that I gained any kind of understanding of the plays. I realized after the first few weeks of rehearsal that he was a genuine playwright who could invent believable human beings. I began to think that all the Shaw plays I had either seen or acted in were mis-directed. I began to say: “When in doubt about Shaw, look for the sex.” This helped, though I would probably now say: “Look for the love.” Nevertheless after arguing — even in Ireland where there is a certain skepticism — that after Shakespeare, Shaw is the greatest playwright in the language, I still found him an almost impossible human being. I didn’t like the man that I glimpsed behind the public persona and in my mind the ugly suburban house at Ayot St. Lawrence seemed to confirm the worst.

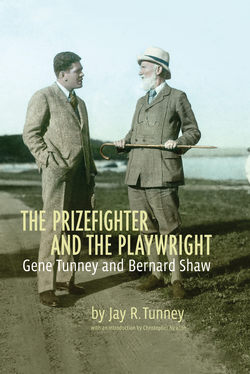

I had to be missing something. Dan Laurence used to talk to me about Shaw being like an onion. Every time you removed a skin, there was another layer underneath, and then another, and then the centre seemed to dis-appear. Well, Jay Tunney in this most attractive book about his father, the famous boxer, and his father’s friendship with Shaw, has given me a revelation. Here is a glimpse of the centre. Here for a few brief moments is the man himself divested of that carping, public voice. The book has at its heart a vacation on Brioni, once a fashionable island resort in the Adriatic. Here, surprisingly, the highly literate Gene Tunney, ex-heavyweight champion of the world now a wealthy businessman, and his wife vacationed with the Shaws. Bernard and Charlotte Shaw found the Tunneys good company — good enough company to actually go on a holiday with them. And for that to be successful you must share interests and values.

Shaw always seemed to have a strong paternal streak in him. He helped and mentored the young Granville Barker. That wasn’t really surprising. After all they were both in the theatre, both, even though Shaw was old enough to be Barker’s father, were making their reputations. Gene Tunney appeared on the scene after the split between Barker and Shaw and he seemed to fill a need.

Of course, Shaw had always been interested in boxing. I would never imagine that Shaw could have been a team player. He needed an individual sport and boxing supplied it for him. He followed the boxing news. He read of Tunney’s defeat of Carpentier in 1924 and was intrigued. When Tunney defeated Dempsey, he made an effort to meet the boxer. Eventually they made contact and Shaw was delighted with this oddly compelling, bookish young man. After all Tunney seemed like Cashel Byron brought to life: a pugilist who loved the arts, who married well and who had risen from a New York Irish working class background to become a major celebrity.

So here are the Tunneys and the Shaws on an island in the Adriatic. The press thought it must be a strange Shavian joke, but as Jay Tunney makes very clear, this just wasn’t the case. I won’t reveal the highly charged event that brought them so close. That’s the heart of the book. But I can say that it moved me and more than anything else that I have read about Shaw, it described a man who I only half suspected might be there — the human being, the vulnerable and compassionate G.B.S.

At one point Jay Tunney writes about the similarity between his father and Shaw. They were both surprisingly private people. The boxer, after his marriage to an intensely discreet wife who hated to see herself even mentioned in the press, was particularly shy of reporters. And yet both men were celebrities and knew it. Shaw exploited this public interest. Tunney, pursued by reporters who never believed that a boxer could read for pleasure, did everything he could to avoid the publicity. Shaw, in private, became the politic and caring father that Tunney wished for, just as he had been the theatrical father that Granville Barker never knew.

This book has sent me scurrying around my own library looking up Gene Tunney in William Lyon Phelps’ autobiography — there’s a chapter devoted to him — finding a reference in Rupert Hart-Davis’s life of Hugh Walpole, realizing that we had a mutual acquaintance in Thornton Wilder. (My connection was fleeting.) A small but important association in the life of a major literary figure has come to life in a most remarkable way. And the story provides a source for incidents in two of Shaw’s later plays and that’s always of interest because ideas seldom occur in a vacuum. There are always connections.

Tunney and Shaw agreed on so many things, but they disagreed about Russia. Shaw, the old Fabian, had always been sympathetic towards the Soviet Union and Stalin. Tunney, the American businessman, was not. But he wanted to see for himself. There’s a curious incident that resonated with me. In the ’30s, Tunney on a visit to Russia arrived at a factory where thousands of church bells, many of them beautiful works of art, were being melted down to make armaments.

I think it was in 1990 — it was certainly the year when Leningrad reverted to its old name — when Cameron Porteous and I were in Russia. We’d spent a day in an artists’ village outside St. Petersburg. In the evening we hopped on a suburban train and arrived at another village. It started to snow and when we got off the train, the Russians in our party suddenly stopped. “Listen. Listen,” they said. We couldn’t hear anything unusual. “Bells,” said the Russians. “Bells. The lost sound of the Russian soul. We haven’t heard bells for sixty years.”

In every town we visited, they were putting the bells back into the churches.

This book is a bit like that. This story of the boxer and the playwright has helped to put the soul back into an author who hid his humanity behind a screen of words. It is a particularly personal book. At times I felt the same fear of intrusion that Jay Tunney’s mother must have felt during all those public years with his father. It is an odd and intriguing book about an odd friendship and a strange and intriguing event.

CHRISTOPHER NEWTON

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EMERITUS, SHAW FESTIVAL