Читать книгу The da Vinci Legacy - Jean-Pierre Isbouts - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Renaissance Studio

ОглавлениеThat idea is not so far-fetched when we consider that the concept of a “studio,” with assistants, pupils, and collaborators, was a unique product of the early 15th century. It was prompted by a sharp increase in the demand for bespoke paintings as a result of the vast wealth that was pouring into Tuscany in the wake of the Black Death of the 14th century. This plague had all but wiped out the fiercest competitors of the Florentine cloth trade, such as Pisa and Siena. When the markets recovered, the mercantile class of Florence gained a near monopoly in the international trade of dyed wool, and as a result enjoyed tremendous prosperity. As we know, sudden ostentatious wealth always seeks an outlet.

And so the traditional role of the medieval painter, as a producer of religious imagery for the Church, was transformed into that of an all-around impresario of objects for the residences of the well-to-do: devotional paintings, to be sure, but also secular portraits; painted furniture (such as marriage chests, known as “cassone”); coats of arms; tapestries; even staged entertainments. Leonardo’s master Verrocchio was often called upon to build all sorts of intricate stage sets and machinery for Medici pageants or masques, as well as costumes, tapestries, and temporary structures such as Roman-style triumphal arches.

This varied output required a staff of skilled assistants, well beyond the normal requirements of a traditional medieval studio. To be accepted as a pupil in a Florentine studio, aspiring artists studied the full range of creative endeavor, including how to draw, to prep wet plaster or wooden panels, to stretch canvas, to sculpt, and to grind and mix pigments in order to create paint (since ready-made paint tubes of the type we use today did not appear until the late 19th century). As the apprentice advanced in skill and experience, he was allowed to transfer a preparatory drawing or cartoon to a plaster or wood surface, or to paint elements of lesser importance, such as details of the background. To acquire such assistants, artists usually accepted promising young pupils at an early age, and trained them through various stages of apprenticeship until they were thoroughly indoctrinated in the style and technique of the master.

This was certainly true of Leonardo, who had been apprenticed to the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio in 1466, at the age of fourteen. It was a mark of Leonardo’s exceptional talent that in 1472 Verrocchio allowed him to paint one of the two angels in Verrocchio’s Baptism of Christ, commissioned by the monks of the San Salvi monastery. Vasari writes that when Verrocchio saw the angel and realized the superiority of this angel to the one painted by himself, “he never touched colors” again.

That’s an interesting comment, because Verrocchio’s rather formulaic style was grounded in the use of tempera, a fast-drying, water-based paint that must be applied quickly and allows relatively few subtle gradations. Leonardo, however, never thought in terms of lines (disegno), but in three-dimensional tones and shapes (colore)—forms that are suggested, rather than defined, through the use of delicate shading and hues. Tempera paint could never achieve such subtle effects. But Leonardo had learned a new technique, that of oils, first developed in Northern Europe. X-ray tests of the Baptism of Christ show that while Verrocchio still painted his figures in contours of white lead, Leonardo used thin, superimposed layers of colored oils to bring his angel to life.9

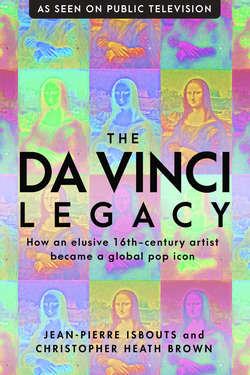

A modern reconstruction of Leonardo da Vinci’s studio in the Santa Maria Novella in Florence, ca. 1504

It is extremely doubtful that Verrocchio “never touched colors again,” as Vasari writes. Verrocchio continued to accept commissions for paintings, for the simple reason that it was a major source of revenue for his bottega. Running a large studio was a risky venture, even in the heady days of Lorenzo de’ Medici’s Florence, and Verrocchio was not a man to take risks. In 1457, he wrote on his tax statement that he was losing his shirt trying to keep his shop operating—the Italian expression is non guadagniamo le chalze, “can’t keep our hose on.”10 It is more likely that Verrocchio delegated much of his painting work to Leonardo, so that he could focus on his principal art form, sculpture.

Andrea del Verrocchio, Baptism of Christ, 1472