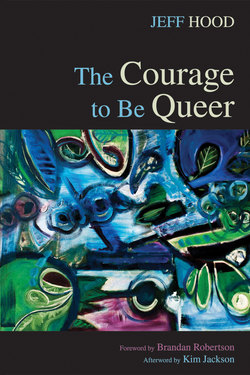

Читать книгу The Courage to Be Queer - Jeff Hood - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеTheology without the practical is dead, and dead theologies do not bring about resurrection. I seek theology that speaks life into death. I believe there is desperate need for a universal theology that can exist among and participate with other theologies and speak resurrection to the entire breadth of human uniqueness or queerness. That is what this project is about. It is my intention to develop a theology of queerness using a queer hermeneutic that is based on a core understanding that human beings are created uniquely queer in the image of a God who is queer and that resurrection comes through the discovery of the Queer within and without. This theology is an attempt to correct the efforts of the church to tame or shun the Queer. I propose that salvation can be found nowhere but the Queer. I am attempting to redefine in a radically inclusive way what it means to follow God. The core of this theology is that the Queer within us is the source from which flows all knowledge of the Queer. When we claim who we are as a unique, queer, individual made by a God who is queer, we are each creating the needed space within our self to interact with the divine within our self. The Queer is the source of universal liberation because the Queer calls all to move beyond the yoke of trying to be something other than queer or what God created us to be. This is a theology of individual liberation. In this queer space of discovery and freedom, I believe that we are finally able to blur constructed and normatized identities to move to a place of acknowledgment that all people are unique, queer individuals made in the image of God and worthy of the individual resurrection of acceptance, community, and love. This is a theology of discovery and reconstruction. This is the story of God drawing queer to queer and queering the world with acceptance through difference and love.

The Courage to Be Queer is an intricate dance between hermeneutical interpretation and theological exploration.1 Throughout this introduction, I will prepare the path for a wider journey into both the chosen self and the chosen texts. In relating personal experience, creating new terminology, and exploring past hermeneutics and theology, I will describe the experiential epiphany of the Queer within me that brought me to this place of hermeneutical and theological construction.

As much as I wish it was not so and that God-talk could exist beyond language, theology has to be constructed using language, and thus terms are important. In “The Start” I discuss where the idea for this project came from. In “Terms of Description,” I explain how I use language to describe my experiences and to construct this work of queer theology.2 It is not lost on me that the word “queer” does not appear in the majority of mainstream translations of Scripture, but I think there are plenty of words and ideas that can be reinterpreted and reimagined to discover the queer within Scripture. In “The Queer Theological Approach,” I illustrate and explicate the reinterpretive theological approach taken in the construction of this project. In a paraphrase of the writer of Ecclesiastes, it is important to remember “there is nothing new under the sun” (1:9).3 In “Precursors Descending,” I illustrate where I see this project falling into the long history of hermeneutical and theological adaptation and reinterpretation. In the conclusion of the introduction and in the beginning of the wider work, I briefly outline the chapters of the project in “The Epiphany of the Queer.”

The Start

I once led a private time of sharing and healing for victims of spiritual violence. Paul walked in and took his seat near the back of the room. After a couple of people told a few stories of harsh evangelical backgrounds, Paul spoke up and described being probed in his anus by members of his Roman Catholic youth group. The intention of the attack was to show Paul how painful being queer could be. People consistently ask me how anyone can morally claim to act in the name of Jesus when such atrocities and violence are consistently committed against queer folk in the name of Jesus. My gut reply surprises everyone, “We have to kill Jesus.” It is an epiphany that has been a lifetime in the making. Unless the Jesus or God of tradition dies, then a God that is as real and queer as us cannot be resurrected. In these moments of epiphany I consistently meet the Queer, but such moments originate in a journey.

Life is filled with experiences of people trying to squash what God has created each of us to be. Religion is one of the chief vehicles used to corrupt the Queer image of God in all people. I come from a Southern Baptist background and was ordained as a Southern Baptist minister. I know a thing or two about religious normatization. My people have attempted to use God, Jesus, salvation, ethics, sexuality, gender, family values, and a whole host of other things to bludgeon people into normative constructs created to control. In my time as a student at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, my heart was crushed by normative constructions on many occasions. Perhaps the chief occasion occurred when one of my closeted fellow students asked a professor what to do if they could not shake their attraction to the same sex. The professor said to pray for death, for it is better to die than live in sin. Needless to say, the professor was attempting to bully the student out of two of God’s most precious gifts: his life and his sexuality. Oppression is an incredibly normative construct. When we realize the queer that we are created by God to be, those who try to steal our queerness from us become not just obstacles in the short term, but the very enemies of God.

In retrospect, I realize that I have journeyed toward the Queer within. The traditional boundaries and identities contained in typical God–talk feel uncomfortable and oppressive. There was always an attempt to control. I found God to be a God of love and freedom, Jesus being the chief expression of such. I, however, always felt like something was missing—something was not right. I discovered the source of my angst when I encountered queer communities fighting the church for the right to express the Queer within. Many of these individuals were lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, but many were not. All were fighting to be able to be who God created them to be. I knew that this was my struggle too: to be who God created me to be. The God who describes God’s self as “I AM” forty-three different places in the Hebrew Bible (e.g., Exod 3:14; Gen 26:3; Zech 8:8), was calling me to the same level of acceptance of whose and who I was: “I AM” queer. When I found myself in the community called queer, I found God as well. The traditional boundaries began to change. Queerness was no longer something to be frightened of; it was something to be sought, embraced, and expressed. It was divine.

Terms of Description

It is my intention to use a queer hermeneutic to develop a queer theology that speaks to all individuals through their individual context or queerness. Throughout this project, I will define queer using a primary definition of that which is non-normative. I see normativity as synonymous with evil or sin. The creation myth provides a beautiful introduction to this concept. The serpent informs Eve in Gen 3:4 that if you eat of the fruit, “you will be made like God.” In turn, the metaphorical fall cannot simply be described as an act of disobedience, as this fails to capture the total illustrative nature of the passage. The fall is both Adam and Eve’s rejection of the God within, or the unique queer individual they were created by God to be, in order to chase the false normative construction of God created by the serpent. This resistance reading of Genesis sees the rejection of the queer individuals God has created us to be as the original sin.4

The level of acceptance or rejection of queerness is best measured using the rubric of love. This rubric can be described on multiple levels based on six theological presuppositions.

First, to reject the Queer within is to reject God. To love the Queer within is to love God. Rejection of the Queer within leads to a rejection of the Queer in the other.

Second, to reject the Queer in the other is to reject the God in the other. To love the Queer in the other is to love the God in the other. Rejection of the Queer in the other leads to a rejection of the Queer in communities.

Third, to reject the Queer in communities is to reject the God in communities. To love the Queer in communities is to love the God in communities. Rejection of the Queer in communities leads to the rejection of peoples.

Fourth, to reject the Queer in peoples is to reject the God in peoples. To love the Queer in peoples is to love the God in peoples. Rejection of the Queer in peoples leads to the rejection of the Queer in the world.

Fifth, to reject the Queer in the world is to reject the God in the world. To love the Queer in the world is to love the God in the world. Rejection of the Queer in the world leads to the rejection of the Queer in the universe.

Sixth, rejection of the Queer in the universe leads to the rejection of the God in the universe. To love the Queer in the universe is to love the God in the universe. Rejection of the Queer in the universe begins with the rejection of the Queer within. Rejection of the Queer in the universe also leads to the rejection of the Queer within. To reject the Queer in the other, communities, peoples, the world, or the universe is to reject the Queer within.

A belief in the intersectionality of all things is vitally important to this construction of queer theology. Love of the Queer within and without begins with understanding the intersectionality of all things and seeking to love all things. Rejection is the antithesis of love, and to reject the Queer is not to love. To reject love is to reject God.

If the antithesis of love is rejection, then love itself can be understood primarily by the sacrifice of acceptance. It is important to note that it does take sacrifice to practice acceptance. To accept the Queer within, we must sacrifice the constructs of normativity that our minds are bombarded with every day through messages that try to convince us that who we are is not good enough. To accept the other, communities, peoples, the world, and the universe, we have to sacrifice the security of non-engagement or isolation. These acceptances are all interconnected. The more we are able to accept the world without, the more we are able to accept the world within. If you want to heal yourself, then you are going to have to love somebody. If you want to heal the world, then you are going to have to love somebody. Love begins and ends with the sacrificial act of acceptance.

In Mark 12:30–31, Jesus says that one should “love . . . God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength . . . You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” To love God, or the Queer, we must push past normative constructions about meaning and value in this life, which often deprive us of being the Queer within we were created to be. To love the neighbor as the self, we must sacrifice our hesitancy to accept or find the Queer within the other. We must value the Queer in the other as much as we value the Queer within ourselves. Jesus, in John 15:13, states, “Greater love has no one than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.” It seems that we cannot lay something down of our own accord unless we know what we are laying down. There is a need to know the Queer in order to give or sacrifice the Queer. One must know the self in order to give or sacrifice the self. In 1 Cor 13, Paul states, “the greatest of these is love.” In the end, though there will be other constructs remaining, love is the greatest. If 1 John 4:8 is correct and “God is love,” then love and God are inextricably linked. Love will always be non-normative or queer in a world of insecurity, violence, and hate. Love will be God, and the greatest measure of that which is queer is God. Queerness functions as that which powers love and, consequently, life. Fitting ways of talking about our experience of this amalgamation of divinity might be: Queer the universe, love. Queer the world, love. Queer your community, love. Queer your self, love. The mystery (or that which is beyond our normative explanations) explodes from the activity of love, which is the very queer creator or core of the universe.

Theologies are constructed from an individual point in time and should speak beyond time. Traditions and histories inform theologies, and this theology will be no different. I will begin the construction of this theology in a place of perfection and conclude in a place of perfection. Perfection, or eschatological hope, is at the core construction of this theology.

The Queer Theological Approach

To pursue holiness is to pursue Godliness. That which is holy is that which is most intimately connected to God. The Queer within is the image of the God who made us. Holiness is the pursuit of the Queer, or God. Queerness is a recognition and pursuit of the God within and without. Queerness and holiness are ultimately synonymous terms. Holiness is pursued and found from where you are—your context.

Since the beginning, theology has always been constructed in context. We speak from where we are. We are always seeking, wondering, loving, fighting, and dreaming from our own time and our location. We raise our voices to speak, to name who and where we are. We wander and grope in the darkness to find the God who made us. We love each other in hopes that we might touch something eternal and transcendent by sharing love. We fight for a more just world because we believe justice is possible. We dream of a world made whole because there is something in us that believes that once, in a faraway place, wholeness was real and perhaps wholeness might be made real again. In a world being slowly demoralized by oppression, those of us who theologize in context choose to believe that there is hope for our local and global community and for us. Theology is an exercise of contextual hope. We are not alone in our efforts, as the consistent incarnation of God in Jesus is the ultimate expression of the continual creation of contextual hope.

In Matt 25:35–36 and 40, Jesus makes it quite clear where the incarnational context of Jesus or God will always be: “I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, naked and you gave me clothing, sick and in prison and you visited me . . . Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these, you did it to me.”5 In the context of the consistent denial of rights, the consistent hate crimes, the consistent religious violence, and other marginalizations committed against those we call non-normative or lacking in their ability to fit our categories or idealizations of acceptance, it seems quite obvious to me that queer folk, or those who defy normatized constructions, are indeed the least of these. The location of the Queer is where we need to go to find God and any constructions of theology that might follow.

In order to arrive at the place where we can look to the Queer to create theology, something must die—namely, rigid normative traditional concepts that are consistently used to oppress. I have often found that traditional concepts of God do not allow room for expressing humanity’s varied experiences of God. Death is not something to be feared, as I do not believe in death without resurrection; things die and create new life. God in Jesus gives up life so that life may be made full. There is a sense in which God is consistently giving and receiving life. The danger of traditional theologians is their unwillingness to open up to the possibility that God’s death and resurrection is the true path to loving acceptance of queerness in the self, each other, the world, and in the divine.

Theology must be contextual, but contextual categories can only take us so far in our attempts to reach a place where we recognize the God within and without. We must realize that context comes from the individual, and therefore theology must spring from the individual. Genesis 1:27 purports that we are created in the very image of God. This means that every human being is a unique reflection of God. It is important to state that God is black. It is important to state that God is brown. It is important to state that God is a lesbian. It is important to state that God is intersex. It is important to state that God is disabled. It is important to say all of these things and more because the individual is important. Constructions of shared identities can help us to understand God, but we must push further. We need to push to a place where we can discover the source of the whole of humanity by championing the uniqueness of the individual so that we may proceed to a place of community constructed in difference. There is something uniting and guiding us, something that draws each of us deep within the self so that we might discover the creator and sustainer of the universe.

There is a need for sacrifice and death in order that we might find the uniquely non-normative source and sum of the entirety of all uniquely non-normative creations. It is irreparably harmful to say that God loves someone but hates a core biological part of who they are. It is divisive and unhelpful to argue that a certain identity characteristic makes one superior to anyone else. No matter the source, words of oppression are shallow and have never made sense. There is a deep need to create a theology that celebrates the unique dignity and worth of all people as individuals so that unique individuals can come together to create honest community. I am interested in a theology that can speak to a woman I met not long ago. She was the product of four different races—her mother was of Mexican and Japanese descent and her father was of Irish and Ghanaian descent—and she also identified as a lesbian. When I told her that I was a pastor, she asked me bluntly, “I have wondered my whole life, where do I fit?” One of the great tasks I seek to accomplish in this project is creating a theology that allows such a woman to be the unique, non-normative creation of God she was born to be in her context. I believe if God is near and here in the diversity represented in every individual, then surely God must be queer.

A resurrection of theology requires a willingness to deconstruct and let die traditional and modern concepts that do not allow room for the Queer, or God. New constructions and ways of thinking must give way to experimental constructions of hope and promise. In the gospels, Jesus consistently deconstructs the egotistical religion. Jesus takes things even further by placing the center of spiritual life outside the normative gates, squarely in the midst of those people a society of boundaries has left out, marginalized, and oppressed. We must stand with Jesus against efforts to divide and disenfranchise by firmly creating theology that upholds the inherent worth of each individual at their core. I am simply no longer comfortable using the same constructions of theology that were used to lock out, deny communion, and brutalize those people deemed out-of-bounds or non-normative by our churches. The theological resurrection I have experienced continues to come in the presence of a God who dares to be queer by God’s very nature and calls us to the same.

Precursors Descending

The theological question of the meaning of the individual as context and source in relation to God descends from a long line of non-conformist theologies and thoughts. In the following study, I will not only show that my line of questioning and constructivist queer theology is not new, but also that it aligns with tradition in challenging non-normativity. In other words, I will attempt to illustrate what I understand my intellectual lineage to be in the construction of this project. I will begin in Ecclesiastes and end in modern queer theology and theory.

“I, the Teacher, when king over Israel in Jerusalem, applied my mind to seek and to search out by wisdom all that is done under heaven; it is an unhappy business that God has given to human beings to be busy with. I saw all the deeds that are done under the sun; and see, all is vanity and a chasing after wind» (Eccl 1:12–14). The words of Ecclesiastes describe the existential crisis that plagues the minds of humans who seek meaning in the world and find only wind. In fact, the entire canonical book of Ecclesiastes is filled with individual speculation and striving for meaning. The canonical book of Job is a description of the search for meaning in the midst of suffering in the early Jewish existential tradition. These two books present scriptural examples and descriptions of the constant struggle to know whether or not the individual is able to connect meaning to God, the other, or the self.

Many centuries later, Søren Kierkegaard began to explore the meaning of existence and faith in the midst of futility. In Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, Kierkegaard consistently describes the need for a leap of faith or love to overcome the cyclical nature of existential thinking. Faith becomes the way out, but faith is difficult to come by. The leap takes a concentration on both the inward and the outward.6 In section 125, “The Madman” of The Gay Science, Friedrich Nietzsche proclaims,

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. Yet his shadow still looms. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?7

Nietzche’s response to Kierkegaard might have been that the task or leap of faith is impossible in the modern age. For Nietzsche, life itself was the ultimate revelation of the futility of life and that God was indeed dead.8 The juxtaposition and struggle between the inward and desire for the outward, however one describes either construct, is foundational to the thought of Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.

The main premise of Martin Buber’s I and Thou is that humans find meaning in relationships. There are two primary categories of relationships: first, our relationships to objects, and second, our relationship to that which is beyond objects. In order to experience God, one must be connected to the immanent and the transcendent. Buber provides much room for a theology that is connected to the individual and that which is beyond the individual.9 Along with Buber, Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time posits that the questioning of the self and the ultimate is at the root of human nature.10 Throughout his works, Jean-Paul Sartre argues that there is no creator, or thou, and “we are condemned to be free.”11 In Being and Nothingness, Sartre argues that being is foundational and nothing else. Buber, Heidegger, and Sartre combine to illustrate the importance of consistently questioning relationships as the essence of being—both the relationship to the self and the relationship or lack thereof to that which is beyond.

Paul Tillich wrote of the courage to be. Being was Tillich’s fundamental theological and philosophical construct. For Tillich, there was something supreme about having the courage to exist: “Being can be described as the power of being which resists non-being.”12 Tillich also described God as the God above God.13 In the theology of Tillich, the being is consistently important, and any experience or connection to a semblance of God happens from the being or the context. In 1961, Gabriel Vahanian published The Death of God: The Culture of Our Post-Christian Era. Vahanian proclaimed that God was dead to the modern secular mind and that God needed to be reimagined or resurrected. Vahanian and the other theologians of the Death of God movement created much theological room for theologians to reimagine God. The Death of God movement and the highly contextual ideas of Paul Tillich combined to inspire the creation of liberation theologies from oppressed and marginalized populations that flowed from context.

In Black Theology and Black Power and A Black Theology of Liberation, James Cone uses his own experiences and the wider experiences of African-Americans to create a theology that posits that God is always most closely described by and connected to the marginalized and the suffering. In these works, Cone pushes the idea that God is black. Later, in God of the Oppressed, Cone argues, “What could Karl Barth possibly mean for black students who had come from the cotton fields of Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi, seeking to change the structure of their lives in a society that had defined black as non-being?”14 For Cone, previous constructions of theology and God were unable to speak to the needs of African-Americans, so previous theologies that seemed to leave out the black experience needed to be allowed to die in favor of reconstructing something new. In A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation, Gustavo Gutiérrez constructs a theology that speaks of God’s dwelling and identification with the poor. The path to the divine liberation of the self comes through the liberation of the poor. Gutiérrez pushes the idea that God is poor. In her Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation, Mary Daly uses ideas of a divine feminine to reimagine God. For Daly, to say that God is masculine is blasphemous. Through race, class, and gender, Cone, Gutiérrez, and Daly sought to create a God who truly was incarnate in “the least of these.” In the coming decades, many other theologians followed suit, daring to believe that liberation would be found in naming their people as the contextual center of God.

In 1968, Anglican priest H. W. Montefiore published a controversial essay entitled “Jesus, the Revelation of God.” In this essay, Montefiore argues that Jesus’ celibacy could have been due to homosexual leanings and that this might provide further evidence of Jesus’ consistent identification with the outcasts and the friendless.15 Troy Perry published The Lord Is My Shepherd and He Knows I’m Gay in 1972. This apologetical text describes Perry’s experiences in founding the Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches and argues for the full inclusion of the broadly defined gay community. Also in 1972, Howard Wells, pastor of Metropolitan Community Church of New York, wrote a provocative essay entitled “Gay God, Gay Theology.” Wells asserts that gay people have a right to God and declares the liberating redeemer to be our “gay God.”16 In 1980, in the seminal Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century, John Boswell argues that homophobia was not a part of the early church and that the church should accept gay people for who they are. Montefiore, Perry, Wells, and Boswell all represent the early stages of formulating a queer theology, and those who followed would bring a high level of diversity.

Carter Heyward’s Touching Our Strength: The Erotic as Power and the Love of God, published in 1989, draws on contextual embodied experience to declare that God not only is present in the romantic relationships of women with each other, but also exists in the very physical sexual acts two women share. In 1990, Robert E. Goss set forth a similar liberation-based theology around gay and lesbian identity in Jesus Acted Up: A Gay and Lesbian Manifesto. Though Goss uses queer language in Jesus Acted Up, it would not be until the publication of his Queering Christ: Beyond Jesus Acted Up in 2002 that Goss would fully explore queer theory within queer theology. Marcella Althaus-Reid took queer theology in a more indecent and systematic direction with the publication of her work Indecent Theology: Theological Perversions in Sex, Gender and Politics in 2000. The text discusses masturbation, erotic scents, sexual encounters, and much more with the idea that both God and theology are happening in these moments. Althaus-Reid does much to take queer theology in a broader direction through indecency. Patrick Cheng posits that the objective of queer theology is to challenge binaries and boundaries in his 2011 work, Radical Love. Through the radical love of God, Cheng argues that all boundaries should be dissolved. Cheng’s recent books, From Sin to Amazing Grace: Queering Christ (2012) and Rainbow Theology: Bridging Race, Sexuality, and Spirit (2013), push further the idea that a God of radical love eliminates boundaries, though Cheng still seems to be very connected to classic language of identity and binaries. For Cheng, love is the unifying force in the universe. From Heyward to Cheng, a broadening of queer theology has taken place. I would like to broaden it further beyond prescribed identities, binaries, and borders to the space of the queer individual.

I have found some of the writings of Chicana lesbian feminist Gloria Anzaldúa to be helpful in describing where I intend to take this project. Anzaldúa writes in This Bridge We Call Home,

Bridges span liminal (threshold) spaces between worlds, spaces I call nepantla, a Nahuatl word meaning tierra entre medio. Transformations occur in this in-between space, an unstable, unpredictable, precarious, always-in-transition space lacking clear boundaries. Nepantla es tierra desconocida, and living in this liminal zone means being in a constant state of displacement—an uncomfortable, even alarming feeling. Most of us dwell in nepantla so much of the time it’s become a sort of “home.” Though this state links us to other ideas, people, and worlds, we feel threatened by these new connections and the change they engender.17

I have found the space that Anzaldúa calls nepantla to be similar to the space I call queer. I feel like this is the space where all individuals are: somewhere between. The easily labeled normative binaries, dichotomies, and dualisms always fail, but when we dare go to the spaces between, we find the space of transformation, and this is also where we find the self and God. Thus, it is from my own nepantla, or queer space, that I write.

The Epiphany of the Queer

I developed a queer hermeneutic based on an understanding that human beings are created to be uniquely queer in the image of a God who is queer and also that resurrection comes through the discovery of the Queer within. I will explore the theology that flows from the use of such a hermeneutic from the pages of Genesis down through the present. Through exploration of the Queer in context, I will illustrate the presence of the Queer in a variety of individuals and contexts. The Bible and human history both reveal the overarching nature of the Queer within and without. I intend to explore the Queer or God in five parts.

The words within the “The Queering” give voice to my mystical experiences of the Queer. Using the developed queer hermeneutic, I intend to explicate moments when I have seen the Queer and encountered the power of God in my own queerness. Visions of love and the Queer have liberated me, and it is important to allow this queer hermeneutical theology to interact with the contextual realities where I discovered it. This space of queerness has served as a launching point for me to discover the God or Queer within myself. The experiences of the Queer within have granted me the ability to create a queer hermeneutical theology. I pray that interacting with the discovery of my queerness will help others discover their own queerness. Upon traversing the meaning of my own discoveries, I intend to bring this queer hermeneutic to consequence on the Scriptures.