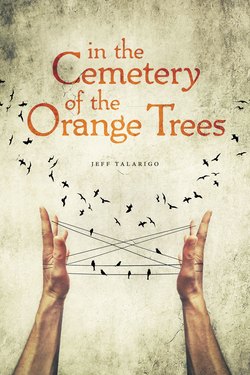

Читать книгу In the Cemetery of the Orange Trees - Jeff Talarigo - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHe has come here, to the land of the forgotten, in order that he may forget, that within their story he may perhaps find his.

His first hour there.

He appears in the city square on a February afternoon, unbeknownst to anyone, a backpack stooping his shoulders. Standing along Salah el Din Street, eating a falafel sandwich, eyes of curiosity are on the stranger, eyes of distrust, but they turn from him and down the street in an instant to where a convoy of soldiers approaches. Above him, unseen, a group of boys lurk on the rooftop, the stones in their hands itch their palms, and when the first jeep is within range they throw them. A loud bang and then another against the side of a jeep startle the stranger. Within seconds the soldiers are shooting at the boys and he, frozen, is caught in the crossfire. There is an alleyway behind him and he escapes into it. People are shouting, throwing anything they get their hands on: rocks, bottles, bananas, a water pipe. An old man yanks off his left shoe and fires it into the throng of soldiers. He watches the old man hobble away, leaving the shoe in the middle of the street. A soldier in the back of a jeep aims his Kalashnikov and shoots dead the shoe.

There is much the American does not know.

That one should never stand beneath the roof where stone throwers are perched. When soldiers pass, make yourself invisible. The waft of tear gas that seared his lungs earlier in the day is produced only forty miles from his hometown. Don’t drink the last of the coffee in your glass. As of late, soldiers have been appearing on the streets, out of uniform, allowing them to get closer to the stone throwers. Sometimes they carry a backpack with a gun inside and then make arrests. The name Jabaliya means people of the mountain, and it is pronounced in even syllables – Ja – ba – li – ya.

This is where he wants to go—the largest camp in the Gaza Strip, the birthplace of the intifada, the uprising. He has no idea how to get there, or if he can even enter the place, only that it is north. Knowing that the sea is a mile away and to the west, he begins to walk through the city, keeping, as best he can, the sea to his left.

He hasn’t been walking long before a voice, in his language, stops him.

“What are you doing here?”

“I want to go to Jabaliya,” he says, mispronouncing the word.

The young man corrects his pronunciation.

“My name is Fayez. That is where I live.”

Several hours later the two of them are walking up School Street and the American is gazing at the expanse of cement block houses. Children get close and Fayez tells them that the man is an American.

“Go away,” Fayez says to the children. They scatter for a second or two, but are back, appearing from everywhere, out of nowhere.

“It’s okay,” the American says, removing his backpack and playing with the children.

And this is how it is the entire way up School Street. Women poke their heads out of colorful doors, men sitting along the cement wall nod to the stranger.

Nearing the house, the American asks:

“Why is it that you are bringing me to your family?”

Fayez watches the American shaking hands with the children and he smiles and says: “I trust your eyes.”