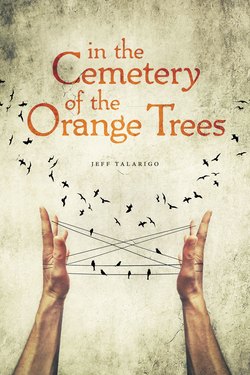

Читать книгу In the Cemetery of the Orange Trees - Jeff Talarigo - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFor a single month, from new moon to new moon, I was the night guardian of the goat. It was a rather simple job, once one got used to the staying awake through the night and following the goat wherever his whims took him: garbage bin to garbage bin, under the willow, or simply to the house where his master, Ghassan Abu Majed, slept away the eight hours and thirty minutes of curfew.

It was exactly in that house, number eighty-eight in block six, in the front room across from the bathroom and kitchen, that the last remaining goat of Ghassan Abu Majed stayed for most of his ten years. A pretty good life for a goat, I imagine. It remained as such until Ghassan’s wife of nearly half a century bolted the door at 7:55 the night before the April new moon, leaving the animal to butt his head against the door until he became tired and fell asleep outside. When Ghassan limped into the dawn air, on his way to morning prayers, he nearly tripped over the goat, lying with his legs curled under, his hooves hidden in the fur of his belly.

Before Ghassan turned around, about to scold his wife for forgetting the goat outside, she spoke to him from the doorway.

“Our grandson is allergic to that beast. The child has been sniffling and coughing since the moment he was born.”

Ghassan held his tongue, respecting the calm hovering over early morning, but the word beast rankled him. He bent over and stroked the goat’s beard until the repetition kneaded away his anger.

“He is the last link to the land.”

“The link has long been severed,” she answered, in a voice also respectful of the hour and of her husband and the goat.

Ghassan balanced himself with his left hand and stood, slowly unfolding his aching limbs. He said nothing more to his wife and headed toward the peace of the mosque. The dust of the camp settled on his sandaled feet, but he ignored it, for he would wash them before prayers.

It was on that very afternoon that Ghassan asked me if I would be the night guardian of the goat. Jobless for more than a year, I said yes.

“Good,” he said. “Now go and get some sleep, your work will begin tonight.”

I went to his house at 7:30 and was given only one order.

“Don’t ever allow the goat to speak or come into contact, in any way, with the soldiers.”

I thought it rather strange that Ghassan used the word “speak,” but I let it pass, for I assumed it to be merely a slip of the tongue. He left me with that message and closed the door, and the goat and I looked at each other and began to walk together up the darkening street. In the pink grapefruit glow of the setting sun, the military watchtower, the tallest structure in the camp, smirked down on us.

That first night, in fact the entire first week, the goat did nothing other than what one thinks a goat would do—sniff through the multitude of possibilities in the garbage on Jabaliya’s streets. That was how we spent the majority of our time: I simply braced my back against a wall while the goat nosed around until he found a tasty morsel. I would listen to and sometimes watch the goat work his jaws, nostrils wet and splaying in rhythm, until the food was mashed enough so that it could easily slide down his throat. Sometimes he would stare at me watching him and I would remember what Ghassan had said. On several occasions, I thought the goat was about to speak, but I laughed at myself for allowing sleepiness to grapple with my imagination.

So it was, the nights passing in near silence, the sickle of the moon growing to half, giving the goat a cleaner white coat than in the harsh reality of the sun.

The quiet allowed much time for thought: of my only son wasting away his youth in an unknown prison for an unknown amount of time, while the moon I watch, then the nineteenth moon since I last saw him, goes about as it always has. But the goat was a distraction. A goat that has divided the people of Jabaliya into two groups—those who believe in its sacredness, the fifth generation of goats from the village of al-Jiyya, the fourth generation living here in this camp, and those for whom the goat is only a bitter, humbling reminder of what once was and never will be again.

And which side do you fall on, I asked myself. A good question, but I am afraid my answer was trapped somewhere in the abyss between trying to forget what happened to my people and trying never to forget. That began to change on my twelfth night with the goat.

About two-thirds of the way through curfew, the goat looked up at me from the wilted leaf of lettuce it was nibbling on.

“Pssst.” The goat pointed his nose down the street.

I must say that I was startled, and had to place both hands against the ground to keep myself steady. When I continued to stare at the goat and not in the direction he pointed, he again nodded his head and spoke the words: “Over there.”

I did as he said and saw, coming up the street, five figures dressed in black from hood to shoe. I didn’t move, hoping that I would become one with the garbage pile and the wall. Across the street and twenty yards down, the figures stopped. Two of them began spray-painting the wall of a house while the others jogged in place, holding small hatchets in the air. I looked at the goat and he too was watching as the wall became a beach of white paint, and then a map of green with a blood-red hawk splitting the country in half. This is how, I thought, the walls of Jabaliya were painted. When the goat looked over at me, I am certain that he was half-smiling and thinking exactly the same thing.

With each passing night, the goat talked more and more. Still, most nights he grazed in silence as we discovered the stories of the curfew-enshrouded camp. We rarely saw the soldiers that I, and I am certain many others among the hundred thousand refugees in Jabaliya, thought were everywhere. These same soldiers who stalked our dreams and dared us to peek out our doors or tiny shuttered windows. In fact, in those first two weeks, I—we—saw soldiers only once, and that in passing. On several occasions, we had seen headlights skulking the streets of blocks five and six, but, although we’d assumed they were jeeps, they could as easily have been workers returning from their cheap-labor jobs in the orange fields and kitchens and butcher shops of the occupiers.

“Where are all the soldiers?” I asked the goat late one night, unusual for me; I usually listened.

The words dangled there for a while before the goat rose on his hind legs, pressing his front hooves against the graffiti-painted wall; each click they made along the cement raced through the encroaching dawn like gunfire. He chewed on a leaf from a locust tree, then another. More time passed before he turned to me and plainly uttered his answer to my question.

“They rule us by our imaginations.”

“How do you mean?”

“Just look at you now. You are studying me standing here, thinking that I look like the soldiers have me against the wall, patting me down, checking my identification papers.”

“So what if I am thinking that?”

“Where else, other than this place, would someone think of something as ridiculous as a goat being patted down by soldiers? How often all over the world are goats doing the same thing, just stretching for something to busy their mouths? And yet, even though you see exactly what I am doing, you don’t pay attention to what you are seeing, but rather, you are imagining, crazy though it may be, what the army has seared into your mind.”

I moved my eyes to the dust. The goat went back to picking at the leaves. If I’d had a watch I would have checked it and kept checking, counting the minutes until my work finished for the night and I could go home to where my wife was making fresh bread, which I would break and share with her before going off to my mat to sleep.

The nineteenth moon had abandoned Jabaliya and the night was cool, not cold, for mid-May. The air held in it the feel of rain, but the rainy season was seven months away.

That night the goat was acting a little strange, not his talkative self, and in the first hours of darkness we had only walked a short way from Ghassan’s. In fact, we were only fifty yards from my house—so close that when I asked the goat if he was okay and he replied that he was feeling slightly chilled, I offered to get him a jacket.

“No, don’t trouble yourself,” he said.

To which I said, “Don’t be ridiculous, the house is a minute away. Come on, you can meet my wife.”

“I’ll stay here and wait.”

“Ghassan told me to never let you out of sight.”

“It’s fine. Like you said, the house is right over there.”

With that I went up the street, but I looked back two or three times, feeling uncomfortable about leaving the goat alone, even for a short while. Once, he raised his leg in a wave, as if he were telling me not to worry. Before opening the door of my house, I looked yet again and the goat hadn’t moved from where he stood. My wife gave me a surprised look when she saw me.

“I have only come for a jacket.”

“Where’s the goat?”

“Just outside.”

“You told me you weren’t supposed to leave him alone.”

“He’s cold. Do we have something he can wear?”

My wife went into the bedroom and came out with a jacket of our son’s.

“This should fit him better than one of yours, although I have never clothed a goat before.”

I wasn’t certain if my wife was joking or not, so I thanked her and went back outside. Down the street, I saw nothing, but I wasn’t too concerned. Each step I took, still unable to see the goat, increased my anxiety, so much so that halfway down School Street I began to run, cradling the jacket under my arm. I searched everywhere, saying nothing, for if the soldiers were in the area I didn’t want to alert them in any way. Then I heard a haunting snicker coming from above. I forced my head toward the sound and saw the goat atop one of the houses.

Relieved that he was okay, I did not question how he came to be up there. I held out the jacket and the goat jumped from the ten-foot-high roof, landing gently on the street.

“Let me help you,” I offered.

The goat lifted his front right hoof through the left sleeve, then the left hoof through the right, and I zipped the coat up his back, careful not to snag his fur. The sleeves were a bit loose, but the length nearly perfect and it fit snuggly.

“Like it was made for you.”

“Thank you,” said the goat.

“Are you hungry?” I held out a piece of flatbread given to me by my wife.

“No, thank you. Let’s rest, I feel tired.”

I placed the piece of bread in the pocket of the goat’s jacket. He led me in the direction of the market and when we drew close, he stopped.

“Why do we allow that tower to stand?”

I turned to the watchtower a hundred yards away.

“What do you propose we do?”

“I don’t propose anything. But imagine how simply we as a group could bring it down. With all the people we have in the camp, we could…”

A beam from the large spotlight stabbed us from above. Blinded, I shielded my eyes with my arm. Soon the headlights from a jeep and then another found us.

“Don’t move,” shouted the soldiers, about thirty yards away. I obeyed them, but the goat moved away from me and closer to the wall.

“We said to stop!”

“Listen to them,” I told the goat, but he acted as though he didn’t hear.

“Not another step!”

“He’s just a goat,” I said.

“I don’t care what he is.”

“A simple goat; he can’t understand you.”

The soldiers edged closer. “What is he wearing?”

“A jacket,” I answered. “He’s cold.”

“You just told me he’s a goat. How the hell do you know he is cold?”

I almost said that the goat had told me, but I caught myself.

“I just know. It’s my goat.”

“Do you have a permit for the goat?”

“A permit?”

“You are not allowed to have any animal without a permit from the army.”

“Goats need IDs?”

The goat took one step and then another toward the soldiers. Several shots were fired. The goat was thrown back ten feet before he hit the ground. He didn’t move. The guns were trained on me.

“You. Go and remove the jacket from the goat. Slowly.”

With guns raised, the soldiers began to back away from us. I went cautiously to the goat and knelt over him. I could see that he was dead.

“You sons of a whore. You killed the last goat from the village of al-Jiyya.”

“Remove the jacket!”

Slowly, gently, I tried to unzip the coat, but the zipper caught and my shuddering hands could not release it.

“Take the jacket off!”

The blood of the goat had begun to pond in the street. I stared at it. Again, I worked on the zipper, and finally, it came free. I lifted the goat’s left leg from a sleeve and began on the right. As I pushed the hoof up through the fabric, the leg broke cleanly in two. Sensing the soldiers about to open fire, I shoved the remainder of the leg through the sleeve and managed to remove the jacket. I held it up for the soldiers to see that there was nothing in it. No bomb. No weapon. Nothing other than a piece of flatbread, which fell to the street.

The soldiers drove away, leaving the both of us where they had found us. I didn’t want to take the goat back to Ghassan immediately. Of course there was no traffic, so I didn’t even bother to move him. Although we were near some houses, no one looked out their doors or windows.

I sat by the goat and didn’t really think that much at all about how I would get him to his master’s house, five minutes away. I didn’t think about what Ghassan would say to me, the person he’d entrusted with the goat. Nor did it occur to me that I no longer had work and would soon return to chiseling away the hours of daytime just to get to the hours of sleep.

I picked up the severed right leg and studied the goat’s hoof. Sturdy, yet delicate. I placed it atop the goat’s body. Every once in a while, the beam of light from the watchtower passed; strangely, it didn’t blind me as before, but somehow seemed now to be a part of me. The light stretched over and past us, across the blocks of six, seven, eight, and nine, and in the direction of the sea, then to the city three miles away, then to the south, and back into Jabaliya. Nothing else happened. My heart continued to knock on the closet of my chest and I listened to it. When I was a child, after playing soccer, I would stick my fingers in my ears and listen to the drumming of my heart. But I needed no fingers in my ears that night.

Like that I waited for the call to prayer, but it didn’t come. Rather, from up the street, the clopping of a donkey cart could be heard and it became louder until it was upon me.

The man, whom I didn’t recognize, spoke to me from the cart.

“What happened?”

“The soldiers killed Ghassan Abu Majed’s goat.”

He looked down at me, the night still slipping into dawn. I noticed for the first time that the man was hauling several dozen watermelons. He stepped down from the cart.

“Let me help you.”

We placed the goat onto the back end of the cart.

“Is this Ghassan, the one from al-Jiyya?”

“Yes, he lives in block six.”

I went back and picked up the jacket and thought that winter was such a long time away, and only the savage months of summer awaited.

I knew Ghassan would be up, for once he had told me he wakes at 4:30 exactly, sleeping away the entire curfew. That way he ignores it. My life, he told me, is fifteen-and-a-half-hour days.

Before the cart made it to Ghassan’s house I saw him standing in the street and he came to meet us. He said nothing, barely gave me a glance, but went to the back of the cart, where he lifted the goat into his arms and carried him away.

I don’t remember if I thanked the man with the cart or not. I cut through the alleyway and home. My wife said nothing as I walked inside; she may have sighed a sad sigh when I refused the food she offered, that I also do not remember.

I heard that Ghassan went to the field where the orange grove once stood and shoveled a grave. He dug and dug, refusing anyone’s help, and while he dug no one left the field, in fact more and more people gathered.

Night had fallen when Ghassan finished digging. So deep was the hole that several men had to link themselves into a human rope in order to help Ghassan climb out.

Well into the incarceration of curfew, the procession left the field and passed through the camp. Everyone was certain that the soldiers were all places—in the alleys, on the rooftops, somehow a part of the graffiti on the walls, even in the willow tree. We could have told them differently, the goat and I, but who would have believed us?

No one saw Ghassan Abu Majed again. The morning after he buried his goat, Ghassan’s wife checked the front room of the house, where he had been sleeping since their grandchild was born eight weeks before. When she didn’t find her husband in the room, she thought nothing of it, believing he was at morning prayers.

She went outside and cleaned the clothes and the sun had begun to scorch them and still her husband had not returned. She asked passersby if they had seen him; all offered their condolences for the goat and added that, no, they had not seen Ghassan.

The heat of summer baked the streets of Jabaliya and dried the freshly washed black jeans of the youth within twenty minutes. Each afternoon at about three o’clock, the men of block six would take their chairs outside into the warm shade of the wall and they would whittle away the late afternoons as Ghassan had for decades. Here, the men talk and dream of the distant days of winter, and when winter comes they think of the days of summer while the rains keep them huddled inside their houses.

Half a year rushes past and it is the first day of winter’s mist, and soon the mist will become droplets of rain and they will plink off the zinc-roofed houses.

My dream of the brittle days of summer is interrupted by a knocking, a tapping more like it, on the front door. I don’t bother to move as I hear my wife walk by my room to the front of the house. She opens the metal door and its creaking reminds me of a job, long since promised and unfulfilled.

There are no voices and the door echoes its moan, shuts. And now there is a tapping on my room door.

“Yes.”

The silhouette of my wife is there and it looks, in the low light, and through my squinted eyes, like another person as well. I say nothing, for my wife will certainly nag me about getting new glasses. When I sit up on the sleeping mat and look closer I see that she is holding a jacket.

“This was hanging on the door outside.”

“Who was knocking?” I ask.

“There was no one there.”

“Coats don’t knock, my wife.”

“There was no one there,” she repeats.

I sigh as I get out from under the blanket.

“Hand me my sweater.”

“Just put this on.” She gives me the jacket.

I do as she says and the jacket is new and warm and it reminds me of my son. I shake off the ruthless thoughts of whether he too is warm on this December morning. Slipping into my sandals, I walk to the front of the house, and before opening the door I turn to my wife, who is right behind me.

“I will fix the door this afternoon.”

She says nothing, and the sound as I open it mocks my procrastination. I look up and down the deserted, damp street and I am about to shut the door when I see the footprints facing me on the stoop.

“There was someone here,” I say.

“Obviously, for the coat didn’t arrive on its own.”

I keep my attention on the ground. The top right corner of the right foot, where the last two toes should be, is missing. Ending at my door, the footprints then go in the opposite direction, back up the street.

Quickly I leave without telling my wife where I am going. Besides, I can hear her words, real or imagined, chasing me up the street. Crazy man. I wear the new jacket, the jacket for my son, following a long-missing man who believes he had a goat that could talk.

I remember what I once heard about Ghassan, many years before I met him. It is something of a legend, I guess, or used to be. As a young man, when he fled to Gaza in 1948, Ghassan carried his goat the entire nine miles, and when they arrived, he whispered a promise into its floppy ear.

Two years later, in 1950, the year the camp opened, Ghassan went out under the giant willow tree and, with a small hatchet, chopped the little toe from his right foot. The following year, on the same day, November 4th, he went to the willow once again and severed the next toe on his right foot. In 1952, the day before the anniversary, his wife-to-be approached him.

“And what are you going to do after eight years?” she asked.

“Take my fingers.”

“And when they are gone?”

Ghassan said nothing and his wife-to-be jumped on the silence and answered her own question.

“If you want to marry me, you will raise the goats, as a memory of our village, and keep your toes.”

And that is what happened—and why I am following, in light rain, the eight-toed footprints up the street. The farther I go, the more I am certain where they will lead me. I continue on, drawn by the inevitability of it all. Once I cross the rusted railroad tracks and enter the cemetery of the oranges, I am guided to a simple grave, a grave I have never visited but know for certain is the goat’s.

The footprints end at the edge of the grave. I stare at them, hugging the warmth of the coat against my body. The drizzle patters off my head and my hair is wet before I realize that the jacket has a hood. I put it on and the rain patters against it, louder but more hollow. How hard must it fall, I wonder, before the footprints will be erased, or is it even possible that it will ever rain that hard again?