Читать книгу Sunnyside Gardens - Jeffrey A. Kroessler - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Suburban City

ОглавлениеNo single set of characteristics defines the livable city. For some, it is a neighborhood of tenements, with small shops on the ground floor and apartments above. Since New York’s low point in the 1970s, blocks once shunned as decrepit and threatening have rebounded through gentrification. Many young families, however, understandably seek a more suburban setting. Lower density means more green spaces for the children, greater privacy, and a quieter environment. No one but an ideologue or a radical leveler would argue that a city cannot accommodate both forms of urban living.

In actuality, suburban areas of the city possess many of the attributes Jane Jacobs attributes to healthy neighborhoods. While there may not be a mix of commercial and residential properties within each block, streets lined with shops are within walking distance of many homes. Rather than the vertical diversity Jacobs praised, neighborhoods like Forest Hills and Kew Gardens possess horizontal diversity.

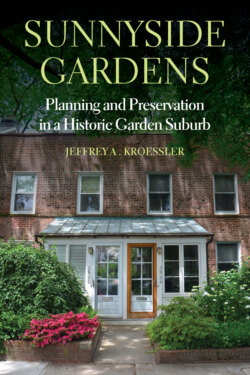

Sunnyside Gardens was one experiment in recrafting the twentieth century city. The designers modified a ubiquitous urban form, the row house, to incorporate generous landscaping and combined the privacy of the one-family home with communal open spaces. It was a housing experiment in the city, but not of the city. Rather, it was a self-conscious alternative to common urban forms. Has the experiment succeeded? Indeed, how would success be measured? After a hundred years, the question is ripe for reassessment.

If it is a matter of emulation of specific form, then we have to accept that the specific plan of Sunnyside Gardens has fostered few imitators. But the founders intended to build a community, not simply houses, and that goal still inspires. While the social motives of the planners of Sunnyside and Radburn may have gone into eclipse over the decades, the design principles endure to a surprising degree. Reston, Virginia (1964), and Columbia, Maryland (1967), both follow in the garden city tradition. Indeed, Robert E. Simon, the developer of Reston, was the son of Robert E. Simon, who served on the board of the City Housing Corporation (CHC); as he planned his new community, he received a personal tour of Radburn by Charles S. Ascher, who had been counsel to the CHC.38

New Urbanism, the movement sparked by Andreas Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk’s Seaside, the community built on the Florida panhandle in 1981, consciously sought to apply traditional architectural forms and planning principles to foster greater social cohesion among residents. In essence, that movement rediscovered the virtues of the garden city. Writing about Celebration, the New Urbanist community developed by the Disney Corporation in the 1990s, Witold Rybczynski noted that the design was infused with the ideal of supporting a sense of community. An executive with Disney Imagineering explained, “We understand that community is not something that we can engineer, but we think that it’s something we can foster.” Indeed, Celebration’s website proclaims it is “not a town, but a community in every positive sense of the word.”39 The builders of Sunnyside Gardens said that a century ago.

Each of these successor places—Reston, Columbia, Seaside, and Celebration—shares with Sunnyside Gardens a desire for a more human-scaled environment. Each was the result of a single, unified vision, and from the start each was governed by strict zoning controls and design standards. In the early twentieth century, garden city advocates were reacting against unhealthy and congested urban environments. The New Urbanists of the late twentieth century reacted against pervasive suburban sprawl. That the New Urbanists struck a nerve with their throwback design principles only demonstrates how far we had diverged from the garden city ideal.40 Interestingly, both the garden suburb advocates and the New Urbanists reached similar conclusions.

This book is divided into two parts. Part 1, “Planning,” addresses the garden suburb idea as it was realized in London and New York in the early 1900s, and how Sunnyside Gardens itself was built, with an analysis of the housing types and landscape. It continues with the story of Radburn and Phipps Garden Apartments, and then the tragedy of the Great Depression, when more than half of that first generation of residents lost their homes to foreclosure. The section concludes with the persistence of these ideas in the New Deal. Part 2, “Preservation,” discusses how garden suburbs have been regulated and preserved, concluding with the designation of Sunnyside Gardens as a historic district by the city of New York in 2007. The last chapter chronicles a controversial proposal to install the 1931 Aluminaire House, an experimental housing prototype, on the only vacant site in Sunnyside Gardens.

Sunnyside Gardens is a small neighborhood in the borough of Queens, but its story is of national, even international importance. That it endures is a testament first, to the ideas of its founders, then to the city of New York’s recognition of its historic significance, and finally to the commitment of its residents to the hopeful ideals embodied in the design.