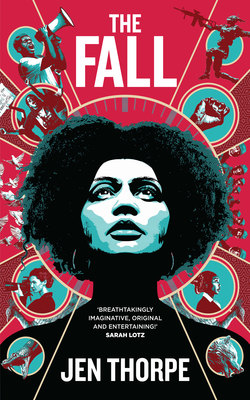

Читать книгу The Fall - Jen Thorpe - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 6

ОглавлениеAdnan

It’s parliamentary party caucus day and you’d think these MPs would be hurrying things along to get out of this committee meeting on time, but they’re dithering. A meeting that could have been finished at least half an hour ago is still going because the members’ egos are flaring.

More and more often I’ve been asking myself what I’m doing with my life. If it weren’t for the money, I would have left here ages ago. At least that’s what I keep telling myself.

I get up each day, brush my teeth, and count the day’s hours in monetary value. Just three hours covers my weekly art class. Another three is Sakhina’s school judo lesson. My lunch break is enough for Mubeen’s soccer training. Then I just have one hour that I save for smokes. Each day I think of new things to pay for with my hours so they have some meaning in real terms. They wouldn’t be survivable otherwise.

Adilah says she’ll divorce me if I quit, not that I’m sure I’d miss her if she did. These days, we are only husband and wife for the legal benefits like cheaper insurance and medical aid. It didn’t start out this way, but somewhere over the years we’ve grown apart. It feels like I stay for the family, and she stays for the lifestyle my salary can pay for. It’s all pretty depressing. I need a smoke break.

I make eye contact with the committee chairperson, pointing to my phone as though I have to take a call, and then sneak out the door.

The marble floors in the National Assembly are a collage of ugly pinks and greys with the occasional mustard. Worse, the lurid pink wall paint makes it feel like you’re navigating a birth canal every time you want to leave the building. My daughter, Sakhina, would say this is definitely not ‘on fleek’, and I’d agree. The Old Assembly building décor is less grotesque, with simple white walls and shiny chequered floors you can see your face in if the light is right.

Stepping out of the shiny corridor and into the bricked Old Assembly courtyard is a welcome respite. Rain or shine, this is a sanctuary where smokers can come together and talk about how much we hate our job, or the weather, or occasionally the rugby. I sit down on my usual bench, closing my eyes for a second to recalibrate.

Smoking is what killed my father, and left my mother alone with weak lungs in a house with walls stained yellow by nicotine. Smoking is what I have left of both of them and it is one thing in my life that always makes me feel better. I doubt I’ll ever stop. Besides, the bitterness of working here is going to kill me before the smoking ever will.

Parliament has its ups and downs, but in the last five years it feels more like things are changing for the worse. The meetings feel more closed and adversarial than when I started out here. My job is supposed to be to advise MPs on content, but you’d think they’re all experts because my support is either ignored or unacknowledged. We’re invisible to them, or when we are visible they resent us. All my years of studying got me to a place where people doubt my intelligence just because I’m not a member of a political party, and where I doubt the intelligence of anyone who is. Those party lines will become hangman’s nooses if they’re not careful.

I open my eyes and take out a cigarette. I hear the door swing open, and two women step into the courtyard. I recognise one as the NCOP chairperson, a short woman who has the aura of a rhino and the stubbornness too. I think the other is the minister of something, though I can’t remember what. I give them a polite smile that they don’t acknowledge, then light up my cigarette, and slouch back into the bench.

I put my earphones in, trying to find a good radio station to listen to on my phone. I feel their eyes on me, but when I close my eyes again, they start talking. Neither one is smoking. It’s like two childhood gossips waiting for someone to look the other way. These two are up to something.

I mute my radio, deciding to eavesdrop. If nothing else, it might give me something to tell everyone over lunch.

The minister starts talking, her voice high and anxious.

‘She’s adamant, Fundi; you should have heard her.’

‘I’m sure she’s being dramatic as usual, that’s all. She’s probably excited about the launch and wants things to go smoothly. She’s a narcissist; it’s just about appearances.’

‘You know that’s not true. Fundisiwe, this could mean killing a child.’

It takes everything in my power not to flinch. I’ve chosen the wrong conversation to eavesdrop on. Killing children is not the lunchtime banter I’d hoped to hear. I don’t want to move and draw attention to myself, and I’ve just started a cigarette. My foot begins to tap involuntarily, so vigorously that they stop talking. Though my eyes are closed, I can feel them looking at me. I force myself to tap it even harder, mimicking the beat of an imaginary song.

‘Ray, that won’t happen. By Wednesday, she’ll have calmed down and forgotten about it. She wants something now, but if you don’t remind her, she’ll move on to something else. If you think of her like a toddler, it helps to manage her.’

‘I need you to take me seriously here, Fundi. She’s asked me not to tell State Security, to arrange it all myself. She’s either setting me up or she fully intends to kill this child. She wants me to try and arrest him in the early hours of Friday morning when everyone is already on the way to the KZN house for her presidential jamboree.’

The president. My legs feel like jelly and my tapping foot loses its rhythm. I open my eyes, bopping my head from side to side, continuing the musical ruse, sucking as hard as I can on the cigarette that seems as though it will never end. I have to get out of here; I don’t want to know any more.

They cast their eyes my way. I can feel my heart pulsing in my neck to the rhythm of their speech.

‘Ray, what is it that you think I can do about this?’

‘Stop this before it’s too late. Stop her. We should have stopped her years ago.’

‘And how do you want me to do that?’

‘She knows you can read her, and she’s afraid of that. Make her think her secrets aren’t as safe as she thought they were.’

‘You think I’m more powerful than I am, Ray. I might be able to read minds but I can’t change them.’

In shock, I inhale too deeply and can’t help but cough, the smoke burning my lungs and throat. Members of Parliament inflate their abilities at the best of times, but it’s the first time I’ve heard any of them claim they can mind read. I cast my eyes to the ground, concentrating on the green weeds poking between the courtyard tiles. If the chairperson can read minds, I don’t want her to know I’ve been listening. I’m almost finished my cigarette, and I’m about to stand when the minister starts talking again. If I walk out now, I’ll only draw more attention to myself.

Acting against every instinct, I settle back into the bench and light another cigarette. For the first time in a very long time, I want to phone Adilah, just to hear her voice.

Oblivious to my growing fear, the two women continue:

‘Fundi, you know that the most dangerous thing about her is that she’s unpredictable. We might think she isn’t going to kill any students, but there’s no guarantee. I’m worried for Sindiwe. I’m scared she’s in danger again. You’re a mother – you must understand that.’

The chairperson’s head drops and she looks at the ground, then takes a deep breath, her shoulders raising her pale-yellow polyester jacket as she does so. She is usually unflustered, even in the face of four hundred unruly MPs. But now she looks worried.

‘Okay, but don’t speak to anyone else, Ray. I’ll talk to Noné and see what I can read. She’s very protective of her mind these days; it’s difficult to know what she’s thinking. But I’ll try.

‘But you also need to be honest with yourself. These students are not going to be peaceful forever. They know the only way we will listen to them is if they do something drastic. Violence is the only official language all South Africans understand. Talk to Sindiwe. See if she can calm them down. Get her off Noné’s radar. Better yet, get her away from those protests altogether.’

She looks as though she’s going to leave, turning her body away from the minister and staring up at the sky. Then, as if she’s heard a hilarious joke, she slaps her hand hard against her side. I want to get out of here more than I want to breathe.

‘Wowu. She keeps us on our toes. You never know what’s coming next. Take him out, she said? Yhu.’ She shakes her head, her jowly neck ricocheting with each action.

‘That’s what she said. Take him out. With the Special Forces and the T-Ruths if necessary.’

‘The T-Ruths? I didn’t know they were ready for use.’

‘They’re not.’

They stand in silence for so long, I almost scorch my lips as my cigarette burns down to the filter. Just when I think they have finished talking, the chairperson starts again:

‘If they’re not ready, then how does she want us to take him out?’

‘She doesn’t care. That’s irrelevant to her. She just wants him gone. And when he’s gone, there’s only one person who will take his place, who will become her next target.’

‘Sindiwe.’

‘Sindi’s just waiting to take charge, Fundi. I can feel it in her like I felt it in Chris. That type of leadership does not allow itself to be silenced. If we don’t stop Noné—’

‘Ray, for now you’re going to have to start making it look like you’re going to do what she wants; don’t let her think you’re delaying. You know she has people everywhere.’

The chairperson turns both beady eyes towards me, and I feel a tingling sensation at the nape of my neck. I stand up and move towards the door, trying to remember what it felt like to walk naturally. My knees feel stiff and unbending.

‘She doesn’t have people in my office. I trust my team.’

‘You shouldn’t, Ray. You don’t know what she’s up to.’

‘Can I trust you?’

‘Ray. It’s me. I know it’s not going to make you feel any better, but she isn’t after Sindiwe. That’s in the past. If Noné wanted to hurt either one of you, she could have done it so many times over the years. That’s not what this is about. It can’t be. You need to let it go.’

‘You have more faith in her than I do.’

As I step back into the corridor, they follow close behind me and I have to pause and hold the door open for them. I watch them walk away and realise I’ve been holding my breath too. My heart races from the cigarettes and the adrenalin, and walking back down the corridors I hardly notice the garish décor. All of it feels unreal.

I sneak back into the committee meeting, collapsing into my chair. Sitting here feels even more farcical after what I’ve just heard. Murder, mind reading, eliminating children – and all with the president involved? Wrapped in my thoughts, I’m startled when the MPs finally stand up and the meeting is over.

When I get back to our office, everyone is sitting around the lounge area, eating their lunch and talking about the crazy things they’ve heard their MPs say in committee meetings that day. It’s a ritual we all participate in, to laugh instead of cry.

As I sit down, the mining advisor is retelling a story:

‘And then she put out her right hand, and said, “On my left is Minister Smuts,” and then when she put out her left she realised what she had done, so said, “and on my immediate left are the committee members.” She didn’t bat an eye. It was hilarious.’

Everyone laughs, shaking heads in mock horror. We’ve all heard it or something like it before from MPs. After a while these anecdotes have become the only way we can relate to one another. They make the experience of working here less depressing.

There’s a lull in conversation while everyone pictures the scene and I take the gap to ask about what I’ve just heard, trying to frame it as a general question. If the president has people watching everywhere, I don’t want to be one of the watched.

‘Hey, does anyone know anything about some Special Forces that we’ve got for policing? “Tearrooths” or something.’

Most of them shake their heads, but Thinus, the defence advisor, looks at me pointedly, his face growing paler than it usually is, making his freckles stand out more. He stands up and, though he’s short and wiry, his presence feels large and ominous.

‘Where did you hear about that?’ His question comes out in a hiss.

My mouth works faster than my brain, thankfully. ‘I think I read about it somewhere this morning, maybe on the train. I was just wondering.’

‘I doubt that’s in the news. If I were you, I wouldn’t talk about it any more. It’s likely to land you in trouble, Adnan. Anyway, what are you doing reading about security? Aren’t fish your thing?’

His tone has turned cold and everyone notices. I don’t respond so the others start to make awkward exits, mumbling that they should get back to their desks. I’m tempted to leave too, but I wait for them all to be gone. I want to see if he has anything else to say. When it is just the two of us any half-efforts to be friendly disappear altogether. His voice is pure venom.

‘I mean it. Don’t go asking about those. There is only trouble that can come from it.’

He says it in a low firm voice, so even if there were others around, only I would hear him. As he walks out of the lounge I realise I’ve been holding my breath for the second time today. When I look down my hands are trembling and I don’t know whether it’s nicotine or nerves, but I know I can’t stay silent about this. Something bad is going on. I have to tell Miles. He’ll know what to do.