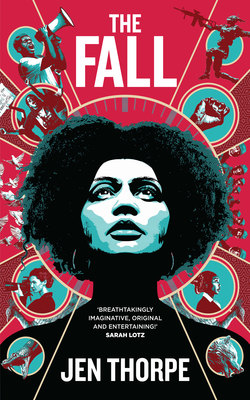

Читать книгу The Fall - Jen Thorpe - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 5

ОглавлениеRay

Noluthando hands me the phone, her normally friendly face collapsing in on itself with concern. When I see who is on the line, my first thoughts are of Sindiwe and whether she’s safe. That much has not changed, over twenty years later. I don’t think it ever will.

‘You better take it, nana – you know she will just call again if you don’t. I’ll make some tea.’

Noluthando walks quickly out of my home office to the kitchen. I strain to hear the sound of the kettle being filled, but the pounding blood in my ears is too loud.

Each time I must speak with Noné, it is the same. My skin prickles; my muscles tense. But speak to her, I must – it is my job. At least if I know what she is up to, I can protect Sindiwe.

‘You’re too deep in thought. You must focus, Ray,’ Noli whispers.

I’m not sure when Noluthando abandoned her post as cleaner and took up the mantle of mothering me, but it’s habit now. She places the Earl Grey with honey next to me, then closes the door. I’m still holding the phone, as though it’s a stone I plan to throw.

Noné’s voice crackles down the line: ‘It’s not polite to keep me waiting, Ray.’

I put the phone to my ear, stifling a sigh. ‘What is it that I can help you with, Your Excellency?’

‘These protests are becoming a nuisance.’

‘I’m sure they will be resolved soon. As far as I know, the Minister of Higher Education has it in hand. That was his brief to Cabinet last week.’

‘We both know that little smiling turtle of a man cannot fix this mess, Ray. It demands a firmer hand.’

‘We’ve already got Special Forces on campus. That alone is an extreme measure.’

‘I think we need to take it one step further.’

‘I don’t follow.’ It’s not that I don’t. It’s that I won’t. I take a sip of tea, the soothing scent of bergamot a stark contrast to the chill in Noné’s voice.

‘I do hate explaining the obvious, but I think it’s time to take him out.’

‘What?’

‘The boy leader – the one with the T-shirts with the catchy slogans and the too-clean tackies.’

‘But, Noné—’

‘Minister, this is the president speaking and this is an official call, not a personal one, so I’d appreciate it if you could address me appropriately.’

The words taste bitter in my mouth. ‘Your Excellency, I think that—’

‘Minister, the protests cannot go on any longer and the Minister of Higher Education seems unwilling to make the necessary decisions. We must take matters into our own hands.’

‘If I may offer my advice, Madam President, this is not the route to take. There are alternatives.’

‘I have not yet asked for your opinion, so you can keep your unsolicited advice to yourself. Don’t let your daughter’s activism blinker you – this is the only way to do things if we want to scare them into submission.’

Is she mentioning Sindiwe as a warning? I place the teacup back down on its saucer, my hand shaking with a combination of fear and anger.

‘Your Excellency, “taking him out”, as you call it … that is a very serious step. If you’re just looking to scare them, then perhaps we could try—’

‘Oh, I don’t mean kill him, Ray. I would never say anything like that, especially not over the telephone.’

Her chuckle sends a rush of goose bumps racing up my neck, then down my spine. She is unafraid, untouchable. This is all just a game for her; I need to beat her at it. My mind scrambles for ideas, ways to stop her.

‘Can you clarify exactly what it is you had in mind? I imagine I would need to brief the Minister of Safety and Security too, and I must be clear about what it is you are asking both of us to do, so that we can of course defend it, should Parliament ask. I assume it’s within the ambit of the law?’

‘Minister, this is not about Parliament, and they won’t be asking any questions. There’s no need to get the Minister of Security involved, either; he’s such a stickler for detail. This is just between you and me, Minister. It’s easier that way. Fewer loose ends to tie up if something goes wrong. Anyway, we women don’t need a man to validate our decisions, do we?’

Another threat, another set of goose bumps. As I listen to her instructions, I can tell it all seems simple to her, black-and-white, not hazy greys. But the lines are not as clear for me. For her, the student protests are a matter of generality. For me, they’re personal. She knows that. I take out a pen and make notes as she talks, trying to steady my hands.

‘Are you still listening, Minister?’

‘Yes, Your Excellency.’

‘I’d prefer it if you got this done by Friday morning. Most journalists will be on their way to my zoo launch then and it will be easier to deflect from the story. Make him disappear, Ray. Use the SFs or the T-Ruths, that’s what they’re there for.’

It’s a mistake. Noné’s impatience has always got the better of her. If we kill Hector, he will move from hero to martyr. If we did this, we’d be killing a child, not a movement.

‘And, Ray, don’t make me get someone else to do it. They could, I don’t know, get the wrong student by mistake …’

I clench my shaking hands and want to scream, but instead I scratch her name into my notepad over and over again until it pushes through every leaf of paper and right onto the wood of the table. I could keep going, straight through the table and into the ground – into the molten core of the earth if it would see her finally burn like she deserves to. But she has me; not obeying her instructions means that she wins again. If I disobey her, either Sindiwe is at risk, or I am, and then Sindiwe will have lost two parents to the same woman.

‘I’ll see what I can do, Your Excellency.’

I cannot clear my words of the scorn that I feel at any thought of her supposed excellence. She hangs up and I finally let out the roar that has built inside of me. Noluthando comes rushing in, her eyes wide and her mouth open with a lifetime of unsaid worries.

‘It’s okay, Noli, sorry. It’s just …’

Noluthando shakes her head at me and takes the cup and saucer full of spilt tea away, giving my shoulder a gentle squeeze on the way out. I put my head on the desk to rest for a minute, but closed eyes always mean remembering.

My lips tremble but I don’t cry. I’m done crying over Noné; I will not give in to my rage again. I want to believe that I’m better than her. Sindiwe helps me believe that I am. I will do anything to protect her from that woman, even if it means Sindi ends up hating me.

When we returned to South Africa all those years ago, I felt that I had to do so many things – stick to my political commitments, work to earn a living, and raise my daughter alone. The movement often took time from me – time that I gladly gave – but it took time from Sindiwe too. I cannot deny that.

I have tried to be a good mother, but as Sindiwe gets older, I wonder if I have spoiled her. I long for her to understand what freedom after struggle means. How it is a delicacy that melts in the mouth, a hunger filled. Freedom that you’re born with is an unpredictable beast, one that doesn’t require goodness or commitment. But who am I to try to control the freedom I fought for, like it is a gift only I can enjoy?

And with the gifts I have given her, I have taken from others, from myself, from her grandmother. I think about Chris’s mom and her life up there alone in the mountains. Not much has changed since before, except that now each morning she wakes up knowing that her son is dead and that I do not share his daughter, the only living part of him that’s left on this earth, with her. I chose protecting Sindiwe, always, over everything, even when that meant letting an old woman form icicles in her heart against me.

Despite my constant protection, Sindiwe is lightning fast in mind and speech, never faltering when she’s explaining all the reasons why I’m not doing things right; why I’m part of the problem, not the solution; why I’m an embarrassment to her. She hasn’t gone as far as to say that she wishes I wasn’t her mother, but I can feel that statement between us sometimes, cold as a gun. The important thing is that I don’t feel the same way.

She should be learning at campus today; instead, she’s there singing and chanting the same songs I sang at her age. Back then I was angry with the government too. I blamed them just like she does. It’s harder to blame them now that I’m one of them. All of us who were once protestors are the targets of the calls for change, and I don’t think any of us know how to receive the message. We channelled so much energy into being heard, we’ve forgotten how to listen.

I look at pictures of her on the front pages of newspapers and feel that same sense of pride I had when I watched her take her first steps, run her first race, take the stage for her high school graduation, yet this time I know that I don’t have anything to do with her success. I promised her an ocean of freedom and I’ve given her just a drop.

Noluthando returns with a fresh cup of tea, always ready to comfort. We’re not that far apart in age but her spirit is able to hold mine like there are generations between us. Officially, she’s our domestic worker. Unofficially, she is what holds our home together.

‘It’s all going to be okay, Ray. It has to be.’

‘Does it?’

‘Of course, baby.’

‘How do you know?’

‘We are through the darkest days now, so we can only tend towards the sunshine. God is with us.’

‘I don’t know, Noli. It’s becoming more difficult to believe that there are still enough of us on the right path to prevent the others from getting lost. What if we’re turning towards a new darkness?’

She takes a deep breath, wringing her hands and shrugging, then points to the ceiling as though her god is there in the white plaster. ‘Then we will rely on God and the good ones to lead us out again.’ She smiles a weary smile, then leaves me to my desperate thoughts.

I used to think we had fail-safes in place, some sort of strategy for when we got lost. We used to think of debate as integral; now we think of it as dangerous. Things have changed since Noné took power. Her phone call is yet another sign of that. I don’t know whom I can trust in my own party these days.

She’s right that Hector is a problem for us at the moment; he’s holding up a mirror that we don’t want to look into. But despite what it may look like on TV, he’s a representative, not the whole effort. If anything, actions like Hector’s are what we hoped for all those years ago when we were their age – participation, honesty, struggle, people holding us in check. Removing him won’t mean an end to anything. If she thinks the students are protesting because of him, she’s wrong. This has been building for some time and her actions have provided plenty of building material.

He isn’t only one young, angry man. He has friends who are equally angry. Arrests can turn violent. If we use the Special Forces, it would exacerbate the matter. The SFs don’t react to shouts and screams. They never negotiate. They do what they are programmed to do without a thought for the consequences, without a thought at all.

If I’m honest with myself, it’s not Hector I’m worrying about. He’s just a photo in the newspaper to me, and he’ll just be another photo whatever happens to him. The truth is, I’ve done worse than arrest a boy like him on trumped-up charges. We all have. It has become part of our job to sweep things under rugs, fold them away, and make sure those rugs are never unravelled.

If we’d never bought these ridiculous machines from Russia, then Noné wouldn’t be able to threaten Hector with them. But it’s too late now; we have them. The deal was signed before we ever had a chance to raise our concerns. I should have acted then, but I didn’t. Now I must work out how both to ignore her instructions and do what she says at the same time.

I unlock the top drawer of my desk, pulling out the flash stick with the data on the weapons, and plug it into my laptop, rolling my neck around my shoulders trying to shake off the tension. Opening the folder and reading their product descriptions, I feel nausea rise in my throat. This is not going to be easy.

Special Forces (SFs) are the very best in post-life warfare. Dead already, they are at no risk of fatality. These finely tuned reanimated soldiers, straight from a supplier in the Central African Republic, have been improved and updated in Russia to use the most recent bio-technology. SFs can go for long periods without damage, are less likely to rape and pillage on their missions, and can be hung up and refrigerated between use.

We were never supposed to use them for public order, just for warfare. But someone leaked it to the police union that we had undead cops, and when the police heard, they threatened to blow the whistle, and refused to send their live officers back into the field, especially with the students. They have kids too.

The SFs can’t achieve what Noné wants now. They’re still basic bodies without much functionality. What she’s asking is to take out one student in a crowd of thousands. That’s going to need the more advanced units, the units I’d hoped we would never have a reason to use. I click on the folder.

The Top Ruthless© (T-Ruths) are the latest artificial intelligence, planned for destruction then self-destruction. T-Ruths can move inhumanly fast and have a better shot than the most skilled assassin. They’re untraceable after use. When they have executed their task, they self-immolate at such high temperatures that any evidence of their existence is blown away with the wind.

In Cape Town, that wouldn’t take long. Noné knows this, which might be why she is so calm about the matter. If we used one with Hector, nobody would ever be able to trace it to us. It would simply kill him, and then disappear. He’d be gone and she could have her party in peace.

But they’re not ready. We haven’t had enough time to test them to make this a safe operation. They are still in the facility. Our lab assistants haven’t completed their voice-response software. They have to be programmed, their settings perfect. Their language prompts are far more complicated than those of the SFs. This is a gamble with lives.

I can feel tears of frustration rising to my eyes as my mind spins through all the reasons this can’t work, and all the reasons it has to. We should have stopped Noné years ago, but none of us were willing to risk our own plans. We were supposed to be making change from the inside but in doing so we’ve allowed her to flourish. Now we’ll all pay the price.

My real worry is not what will happen to Hector; it’s the absence he’ll leave behind. An absence that Sindiwe will fill, whether I warn her or not. It wouldn’t be the first time that Sindiwe’s life has been in Noné’s way, and I’ve seen before just how far she’s willing to go.

I pick up my keys, leaving another cup of tea to get cold on my table. There is only one person who can help me, who knows more of Noné’s secrets than she does of theirs. Thank god it’s caucus today. I have to talk to Fundi.