Читать книгу A Drop in the Ocean - Jenni Ogden - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FOUR

ОглавлениеI had begun to talk to myself, out aloud. I also talked back to the radio. If this continued I’d be a raving lunatic by the time I left this island. Since I got there ten days earlier I’d spoken to only two flesh-and-blood people—Jack and Nick excluded—and in total time, I couldn’t have spent more than three hours in their company.

In Boston, I relished my weekends of isolation after being duty-bound to communicate with the others in my lab all week. When I arrived on the island I was anticipating with rampant pleasure being on my lonesome for twelve whole months. Now I’m desperate for the sound of a human voice other than my own, or a disembodied radio substitute.

Basil was a man of few words and I couldn’t see myself spending hours with him. And Tom the turtle whisperer was hardly going to be hanging around, waiting for another excuse to slurp wine with me. He couldn’t be much older than thirty-five.

An image of his body inserted itself between my thoughts again. I rolled my eyes, ignoring the fact that there was no one there to notice my exasperation. Naked men do not, in theory, do anything for me. I did, after all, train as a doctor and even worked as one for a brief period. On the other hand, the last time I’d seen a naked man in the flesh had been more than twenty years ago, and my memories of that occasion were, thankfully, dim. So perhaps I could be forgiven for replaying the image of a wet, brown, healthy male body, especially as I was too embarrassed to make the most of the vision at the time. I could feel myself blushing at the very thought. And his casualness with the whole thing. He was probably used to walking about in front of women stark naked. A matter of course for the younger generation.

But he had seemed genuine about my going out with him when the turtles were laying. I noticed he didn’t ask me if I’d like to accompany him and his friends on the turtle rodeo. Thank goodness. I might have said yes and then I’d have had to find an excuse not to go.

Concentrate on the memoir, woman. Boring, boring, boring. Who was I kidding? No one was going to want to read this. A pedestrian account of a dried up, middle-aged academic’s broken dreams. Not even that, really—just tedious descriptions of working in a lab. But I had to do something for the rest of the year. For people not keen on going in the sea, there was a limited selection of activities to choose from. Bird watching, walking.

I snapped shut my laptop, grabbed my binoculars and hat, and set out in the direction of the wharf. Time to find some other people to converse with. They must be out there somewhere. Where do Tom’s research assistants live? What about those kids I saw; they must have parents. Stop moping woman, and get a life.

TO MY SURPRISE I DID MANAGE TO STRIKE UP A conversation with the mother of the two children I had seen. Violet was her name, and she seemed very friendly. Five-year-old Chloe and two-year-old Danny were the sort of kids I like, lots of fun, and Violet intended to homeschool them until they had to go to secondary school. Lucky, lucky kids. Bill, one of the two men who assisted Tom with the rodeo, was her husband. She invited me over for lunch on Sunday so I could meet some of the other islanders.

As for Tom, I saw him in the distance once, on his boat leaving for another rodeo. I stayed well away from the wharf for the rest of the afternoon so I wouldn’t have to talk to him when he returned. I’d had some success in banishing his body from my thoughts, but what if he was at this lunch on Sunday? At least he was unlikely to be naked.

On Saturday there was the excitement of the supplies boat arriving. On Jeff’s instructions I had given Jack a grocery list and a blank check when he brought me over to the island, so I got three more boxes of food and drinkable water, and a letter from Fran. In return I gave Jack my next grocery list and a letter for Fran, and another for my mother, on the other side of the world in the Shetlands. Strange to think Mum and I were both living on remote islands—not a prediction either of us would have made five years earlier. Fran’s letter made me both homesick—they had already had their first snowfall—and happy that I was here in the tropics and not there for the long winter ahead. It brought home how much I missed not having Fran to talk to, although in truth we never talked more than fortnightly when I was in Boston. I couldn’t quite see Violet becoming a soul mate, nice though she was.

I’d just finished reading Fran’s letter when four people—two guys, two gals—showed up at the cabin, large packs on their backs and each carrying a food box. My first campers. I think I disguised the fact that I was a newbie and didn’t have much clue about what my role was other than to show them the campsite and tell them how much it would cost. I asked them how long they were planning on staying and they said they didn’t know, but two weeks at least given they were dependent on the supplies boat to get away. They seemed happy enough, and I left them to it.

At midday on Sunday, I trotted off to Violet’s lunch, carrying a bottle of wine and feeling like an adolescent going to her first teenage party. Whatever would these Aussies make of me? I could hardly be more of a fish out of water.

I was the first to arrive, and Bill was in the process of cleaning his barbecue. He looked about forty, and he told me that he and Violet had been on the island for three years, ever since he’d been made redundant from his job in Sydney. Apart from helping Tom out when he needed it, he and Violet managed a group of four holiday cabins for an absentee owner, and also ran a low-key café in the holiday season. They loved it and intended to stay until the kids had to go to secondary school.

Over the next hour four other guests appeared, including Basil, Ben—the third rodeo man—his partner, Diane, and Pat Anderson, a gray-haired woman who looked as if she might be in her early sixties. Ben and Diane were from England, in their twenties, and working their way around Australia. They had been there since June and planned to stay until April of the next year. Diane was helping Violet with the cabins and Ben was helping Tom. Their real love was scuba diving, and that’s what they talked about most of the time. Pat was a retired teacher. After her husband died a few years earlier she’d decided to live on the island, in their holiday house, permanently. She told me she swam and snorkeled every day, and invited me to join her. I explained I had a writing project that took most of my time and that I wasn’t a swimmer. If you can float, she informed me, you can snorkel, and if you are going to live here, snorkeling is a no-brainer. I smiled and changed the topic to books, another of her passions.

By this time we all had plates piled high with the most delicious seafood I had ever eaten, some of it caught by Bill and some brought along by the other guests. I discovered that there were areas nearby where fishing was permitted, and Bill and Ben both offered to drop me off a fish from time to time. It seemed that the entire permanent island population was there now except for Tom. I could feel myself relaxing and enjoying the balmy air, and the laid-back conversation. I pushed away the little niggle of disappointment. Perhaps he was off island? Perhaps he went back to the mainland with Jack for some reason? I finally managed to bring his absence up in a conversation with Ben about the turtle rodeo.

“Tom seems like he’d be a good person to work with,” I remarked. “Isn’t he into social occasions like this?”

“He’s a bit of a loner, but he’d usually be here, especially if it’s just the locals. He’s not so keen on the tourists. But he’s off on one of the other islands for the next week checking for nesting turtles; they’ve just started coming up.”

“Oh,” I said. “I didn’t realize the turtles laid on other islands. Are they far away?”

“Depends. There are a few small cays within about two hours from here that Tom goes to regularly.”

“How does he get there? In Jack’s boat?”

“No. He goes in the tinnie we use for the rodeo,” Ben replied.

“Tinnie? What’s that?”

Ben laughed. “That’s what the Aussies call a dinghy.”

“Isn’t that a long way to go in such a small boat?” I asked.

“Not for Tom. He knows what he’s doing. It can be dangerous if the weather gets up, especially in cyclone season, but that’s a few months off yet. Don’t worry, he’ll be safe as houses.”

“Goodness, I’m not concerned. I was just curious, that’s all.” I laughed gaily, and Ben grinned.

“Ah yes, he’s an intriguing fellow, our Tom. A man of mystery.”

OVER THE NEXT WEEK I BEGAN TO FEEL AS IF I BELONGED. I wandered every track on the island, spent a couple of evenings talking with the campers and sharing some beers with them, and stopped by Basil’s house for a cup of tea one morning. He offered to let me check my e-mail, so I did, but found that I could delete all but about six messages without even reading them. Of the six I did read, five were related to leftover university business. The sixth e-mail was from Rachel, telling me she was enjoying her retirement but missed the lab sometimes. Fran knew not to e-mail me here. I logged off with a sigh of relief and a firm decision not to bother with e-mail again. It was too much of a reflection of my sad social life.

One moonlit night, right before high tide—when I had been told that the nesting turtles came up—I walked the beach, and was disappointed when I didn’t see a turtle. I did meet Bill, who was also checking for turtles, and he told me that it was still too early in the nesting season for there to be many. For some reason they started nesting a week or so earlier on some of the uninhabited cays where Tom had gone.

On Thursday morning, Violet, Diane, and Pat appeared with a plate of scones and a banana cake, and said they had come for their gossip group. I was quite overcome. I can’t imagine such generous sharing of friendship happening so easily in Boston, or for that matter in England. My new friends told me they rotated around each other’s houses every Thursday morning, and I was the first American they had ever had in the group. I explained that I was in fact British by birth and upbringing—and I thought by accent—but they said they would overlook this. They stayed for two hours and the conversation never faltered. They talked about books, food, star signs, education, politics, and their families, and drew me into every topic without me noticing. My memoir writing fascinated them, and when I tried to explain, rather unsuccessfully, what the point of it was, they enthusiastically interrupted with their own ideas. They didn’t know what they were talking about, of course, because they didn’t know me and my limitations, but later I wondered if I could write a sort of parallel personal memoir about my life. The problem is—and of course I couldn’t admit this to them—I didn’t have a personal life. That had stopped around the time I completed my PhD.

Nevertheless, it wouldn’t hurt to try. I could write up bits and pieces about my past life, just to see if I could write more creatively. As a kid, I loved to write. So on Saturday, after I had eaten the fish Ben had dropped off earlier, I opened a new Word document and headed it My Life. I thought I’d begin by writing about my friendships at school as a sort of comparison with these easy relationships my new Australian friends shared. Had I always been so bereft of friends? Surely not. By midnight I had had enough of feeling miserable, angry, annoyed, irritated, frustrated, lonely, and sad about the words that spilled out of me once I got going. I went to bed and slept fitfully, waking every hour, hot and vaguely disturbed by something I had been dreaming about but which was now gone. I got up and opened my laptop and reread what I’d written:

I remember my first friend at school when I was five. She was pretty and called Julia. We stayed friends until I was taken away from that school when I was eight. I must have had other friends back then, but can’t remember anyone in particular. Other than Julia, my best friend was my father. He was always fun, and on the weekends, when he was home, he’d take me somewhere new in London. We’d go on buses and the underground and he’d treat me just like a real person. Looking back, I’m not sure if he behaved like a kid or if I behaved like an adult—perhaps it was somewhere in between—but the important part was that we loved doing things together and being together. Sometimes Mum came with us, and that was okay, although she never quite got it—our silliness. But she tried to enjoy herself. Even when I was little I think I could sense her embarrassment when Dad tried to kiss her in public. “Stop acting the goat,” she would tell him, pulling away.

Dad was a freelance journalist, and that’s why he spent a lot of time away from home. We lived in a smallish townhouse with an even smaller garden in Chelsea, but it was a nice house and a nice area. When Dad was home he walked me to school every morning and Mum picked me up and walked me home every afternoon. I wanted a little sister like Julia had, but when I asked Mum why she didn’t have another baby she went quiet and turned away. Dad jumped in and swung me up in the air and told me that I was all they wanted; our life was perfect without more kids. I didn’t ask again but I often wished I wasn’t the only one. Even a brother would have been better than nothing.

When I was eight everything changed. Back then I didn’t realize that the happiest days of my life were already over. Dad moved out. He and Mum told me one Saturday night after Dad and I had spent the afternoon at the Science Museum. It was cold and wet, so that was about all there was to do. Mum was trying not to cry and Dad was sad. I screamed at them and stamped my foot and ran out of the kitchen and locked myself in my bedroom. Next morning, when I finally came out, Dad had gone. Mum and I had to move to a tiny flat over a greengrocer’s shop in a horrible street in a horrible, scary part of London. The street smelled and was always filthy. I had to go to a different school where nobody liked me. They all had their little groups of friends and they weren’t letting me in. Not that I wanted to be friends with any of them. They were rude and scruffy and laughed at my voice and my clothes. They called me toffy-face. I told Dad when he came to take me out for the day, and he said it was because they didn’t know any better. They thought I was posh, and that made them uncomfortable. He told me to just keep being friendly and in a while they would see I wasn’t really any different from them. But he was wrong and they never liked me.

I went out on the deck and looked up at the starry sky. Through the trees I could see the lagoon, as still as a swimming pool. The moon was rising late tonight, and I watched as it peeked above the horizon, then soared into the heavens, perfectly round. Back in the cabin, I made a cup of tea and sat down at my computer again. Better that than lying in my hot bunk feeling sorry for myself.

Once a week in the summer term our whole class would get the bus to the public swimming baths and have swimming lessons. Dad had already taught me to swim because that was one of his favorite things. He loved scuba diving and he always said he’d take me away when I was older to a tropical beach where I could learn to snorkel and see the amazing world beneath the ocean. So I was quite excited about going to the swimming baths and thought that the other kids might like me better when they saw I could swim.

How wrong I was. First we all had to swim across the pool one at a time so the swimming instructor could see what level we were at. Most of the kids couldn’t swim at all and just walked or floated holding on to a board. I did freestyle and then the instructor asked me if I could do other strokes so I went across the pool again doing breast-stroke, then again doing backstroke. After that, the instructor said we could all play together in the shallow end for ten minutes before we had a lesson, and he went off to the other end of the baths for a smoke with our teacher. As soon as he had gone, two of the biggest boys jumped on me and pushed me under and held me there. I was sure I was going to drown. When they let me up I was coughing and spluttering and crying and I could hear all the kids laughing, and they pushed me under again. But I came straight up because the teacher had heard them and was shouting at them from the side. The instructor hauled me out and I scraped my knee on the side. Then the teacher told me to go and get dressed, and when I came out I had to sit and watch while the other kids had their lesson. That night I couldn’t go to sleep and I was crying and Mum came in and asked me what was wrong. When I told her she gave me a quick hug but then said I just had to toughen up now that I was nearly nine. She said that if I acted like I was scared they would just bully me more. So I decided there and then never to cry in front of anyone ever again. And I never have. But I never made a single friend at that school.

When I was eleven, I passed the eleven-plus exam and went to grammar school. That was better because the girls there were more like me, and I got on all right with a couple of them. I didn’t very often do much with them outside school hours, though, partly because I had to get the bus home and it was an hour’s drive. Mum said I could invite someone home for tea and to stay overnight, but I never did. I think I was a bit ashamed of our flat and the smelly street. Once I went to a party at one of the girls’ homes and stayed the night—it was a pajama party—and her house was about three times the size of the house we used to live in.

Mum didn’t seem to have any friends either. She worked in a bookshop a couple of streets over from our flat and all she did apart from that was read. So Dad was still my best friend. I saw him about once a month, when he was in London, and he would take me out for the day on a Saturday or Sunday. But best of all was in my summer school holidays when Dad and I would go away together for a whole month. When I was nine he took me to Greece, where we sailed around the islands on a boat with friends of his. He had a girlfriend who was nice to me but she didn’t last. When I was ten we went to Egypt, just the two of us, and stayed in an apartment on the Red Sea. That’s where I first went snorkeling. It was beyond words and made up for all the bad things I had ever experienced. When I was eleven we went to the Bahamas and stayed in different places where Dad and his new girlfriend could scuba dive and I could snorkel. That’s where I had my first scuba diving lesson. The next year it was Belize. Dad had the same girlfriend this time. We went to a little island and as soon as we got there Dad said he’d go and check out the diving first and we could all go together the next day after we’d had a good sleep. But we didn’t and I’ve never been in the ocean since.

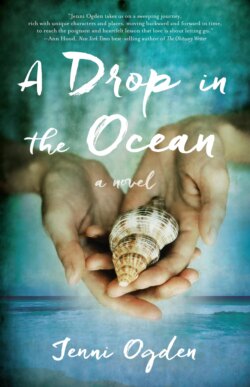

When I finished banging away it was a bit after four in the morning. I closed My Life, pulled on my shorts and a T-shirt, and went down to the beach. The moon was now high in the sky and the sea well over the reef. It was unbearably beautiful. I sat on the sand and a few tears squeezed out of my eyes. I wiped them away and licked one off the side of my hand. The salty taste made me smile, and more tears welled up and slid down my cheeks. I hadn’t cried, even when alone, since I was in my twenties, and it felt wonderful in a strange sort of way. Then I saw a dark shape pop out of the sea, only a short stone’s throw from where I was sitting. I could see her bright eye in the moonlight and then her head disappeared and I stayed still and quiet. Up her head popped again, and this time her great shell followed. I hardly dared breathe as she hauled herself on to the sand and then lolloped on her great flippers up the gentle incline of the beach. Every four or five lollops she would stop, her eyelids closing over her big eyes, and then she would start again. I felt exhausted just watching her. Exhausted but exhilarated at the same time.

As she passed me I could have reached out and touched her, she was so close. A little farther on after another long rest she made it to where the trees began. After a few experimental flips of her long front flippers in the dry sand, she began digging, using her flippers to shoot the sand away from her, gradually making a saucer in the sand, and then a pit. When it was so deep she’d almost disappeared, she began to use her right back flipper as an elongated scoop, delicately inserting it into the deepest part of the pit and extracting the damp sand that lay below the drier sand on the surface. I had crept up to her by this time and was kneeling just behind her and to the side. Every so often I would get sprayed with sand, but I didn’t move. In the moonlight I could see into the deep hole she was fashioning, narrow at the top and ballooning out deep down in the damp sand. How long this took, I couldn’t say exactly, but at least thirty minutes.

At last she was happy with her nest, and she squatted and inserted what looked like her tail into it. And then in the moonlight I saw a translucent, white, perfectly round egg ooze out of the end of her tail and plop down into the depths of the hole. It was bigger than a golf ball. Then came another and another, and I started counting. When she had dropped in eighty-two eggs, she blinked a few times and I could see tears in the corner of her eyes. She closed them for a few minutes before retracting her cloaca—I had figured out it wasn’t just a tail—and, using her back flippers again, began to fill in the nest.