Читать книгу A Drop in the Ocean - Jenni Ogden - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE

ОглавлениеOn my forty-ninth birthday my shining career came to an inauspicious end. It took with it the jobs of four promising young scientists and catapulted my loyal research technician into premature retirement, an unjust reward for countless years of dedicated scut work.

That April 6th began in precisely the same manner as all my birthdays over the previous fifteen years—Eggs Benedict with salmon, a slice of homemade wholemeal bread spread thickly with marmalade, and not one but two espressos at an Italian café in downtown Boston. On my arrival at eight o’clock sharp, the elderly Italian owner took my long down-filled coat and ushered me, as he had for more years than I care to remember, to the small table by the window where I could look out on the busy street, today frosted with a late-season snow that had fallen overnight and would soon be gone. He always greeted me with the same words: “Good morning, Dr. Fergusson. A fine day for a birthday. Will you be having the usual?” as if he saw me every morning, or at least every week, and not just once a year.

Perhaps the unusually deep blue cloudless sky, almost suggesting a summer day, should have warned me that something was not quite as it should be. But superstitious behavior is not a strength of mine, and after my indulgent breakfast I walked to my laboratory in one of the outbuildings of the medical school, taking pleasure in the crisp winter air and stopping to collect my mail—in this e-mail era, usually consisting only of advertising pamphlets from academic publishing houses—before entering the lab.

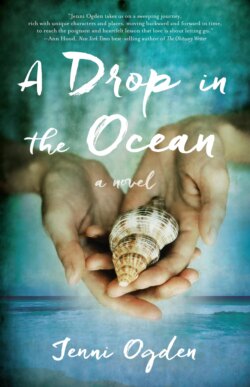

Rachel looked up from her desk with her hesitant smile and gave me a beautifully wrapped parcel—a good novel, as always, the thirtieth she had given me. One for every birthday and one for every Christmas. I have kept them all. “Happy birthday Anna,” she murmured, not wanting to advertise my private business to the others in the lab. Two of my four young research assistants were already at work, hunched over their computers. The other two would be out in the field interviewing the families who were the subjects of our research program. Huntington’s families, we called them.

The research I had been doing for the past twenty-four years—first for my PhD, then as a research assistant, and finally as the leader of the team—focused on various aspects of Hunt-ington’s disease, a terrible, genetically transmitted disorder that targets half the children of every parent who has the illness. Often the children are born before the parents realize they carry the gene and long before they begin to show the strange contorted movements, mood fluctuations, and gradual decline into dementia that are the hallmarks of the disease. Thus our Huntington’s families often harbored two or three or even four Huntington’s sufferers spanning different generations.

Thankfully I was spared having to deal with them; I have never been good with people, and especially not sick people. I didn’t discover this unfortunate fact until my internship year after I graduated from medical school. But as they say, when a door closes, a window opens, and I became a medical researcher instead. Of course it took a bit longer, as I had to complete a PhD, but that was bliss once I realized that my forté was peering down a microscope at brain tissue.

So there I was on my forty-ninth birthday, looking at the envelope I held in my hand and realizing with a quickening of my heart that it was from the medical granting body that had financed my research program for fifteen years. Every three years I had to write another grant application summarizing the previous three years of research and laying out the next three years. Every three years I breathed a sigh of relief when they rolled the grant over and sometimes even added a new salary or stipend for another researcher or PhD student. I had become almost—but not quite—blasé about it. The letter had never arrived on my birthday before; I had not been expecting it until the end of the month. So I opened it with a sort of muted optimism. After all, it was my birthday.

“Dear Dr. Fergusson,” I read, already feeling lightheaded as my eyes scanned the next lines, “The Scientific Committee has now considered all the reviewers’ comments on the grant applications in the 2008 round, and I regret to inform you that your application has not been successful. We had a particularly strong field this time, and as you will see by the enclosed reviewers’ reports, there were a number of problems with your proposed program. Of most significance is the concern that your research is lagging behind other programs in the same area.”

I stared glassy-eyed at the words, hoping that I was about to wake up from a bad dream with my Eggs Benedict still to come.

“The Committee is aware of your excellent output over a long period and the substantial discoveries you have made in the Huntington’s disease research field, but unfortunately, in these difficult financial times, we must put our resources behind new programs that have moved on from more basic research and are able to take advantage of the latest technologies in neuroscience and particularly genetic engineering.”

My head was getting hot at this point; latest technologies and genetic engineering my arse. Easy for them to dismiss years of painstaking “basic research,” as they called it, so they could back the new sexy breed of researcher. No way could they accomplish anything useful without boring old basic research in the first place.

“A final report is due on the 31st July, a month after the termination of your present grant. Please include a complete list of the publications that have come out of your program over the past fifteen years. A list of all the equipment you currently have that has been financed by your grant is also required. Our administrator will contact you in due course to discuss the dispersal of this equipment. The University will liaise with you over the closure of your laboratory.

We appreciate your long association with us, and wish you and the researchers in your laboratory well in your future endeavors.”

The other tradition I kept on my birthday was dinner at an elegant restaurant with my friend Francesca. I could safely say she was my only friend, as my long relationship with Rachel was purely work-related, except for the novels twice a year. I was tempted to cancel the dinner and stay in my small apartment and sulk, but something deep inside wanted to connect with a human who cared about me and didn’t think of me as a washed-up old spinster with no more to discover. Fran and I had been friends since our first year at medical school, when we found ourselves on the same lab bench in the chemistry lab, simply because both our surnames began with ‘Fe.’

Fran Fenton and I were unlikely soul mates. She was American, extroverted, gently rounded, and ‘five-foot-two, eyes of blue,’ with short, spiky blond hair. I was British, introverted, thin, and five-foot-eight, eyes of slate, with straight dark hair halfway down my back, usually constrained into a single plait, but on this occasion permitted to hang loose. Fran was also, in stark contrast to me, married, with three boisterous teenagers. She worked three days a week as a general practitioner in the health center attached to the university where my lab was, and we did our best to have lunch together at least once a fortnight. I once went to her house for Christmas dinner but it wasn’t a success; her husband, an English professor, found me difficult, and her teenagers clearly saw me as a charity case. But the birthday dinner was always a special occasion for Fran as well as me, I think.

When she read the letter she was satisfyingly appalled, and said “swines” so violently that there was a sudden hush at the tables around us. When the quiet murmur in the room had resumed, she reached over and put her small, pretty hand over mine. I felt the roughness of the skin on her palm and blinked hard as I realized what a special person she was, never seeming rushed in spite of the massive amount of stuff she did—including slaving over a houseful of kids. Her eyes were watering as well as she said softly, “It’s so unfair. How could they abandon you like this in the middle of your research? What will happen to all your Huntington’s families?” Sweet Fran, always thinking of the plight of others worse off by a country mile than people like us, whereas all I’d been thinking about was myself and how I’d let down my little team. I blinked hard again and turned my palm up and grasped her hand. I’d been aware how close to tears I’d been all day, but of course I hadn’t allowed myself to succumb; not my style at all. In fact my brave little team all remained tearless as I gave them the news at our regular weekly meeting, which just happened to be today. Rachel had disappeared into the bathroom for a long time as soon as the meeting was over, and when she finally reappeared looked distinctly red-nosed. That’s when she told me that she would take this opportunity to retire and go and live with her elderly sister in Portland. Dear Rachel, loyal to the end.

Fortunately, the last PhD student we had in the lab had submitted her thesis a couple of months ago. I’d promised my four shell-shocked researchers that I would personally contact every lab that did research similar to ours and put in a good word for them. They had become quite attached to their Huntington’s families, which is not a recommended practice for a research scientist, but was a characteristic that I’d learned was essential for effective field workers. Releasing four Hunt-ington’s researchers on to the market at once was practically a flood, but they were young and good at what they did and would surely get new positions in due course.

Fran was asking me about other grants, and I wrenched myself away from my gloomy reverie. Taking my hand back, I grabbed my wine glass and emptied it. “Not a chance, I’m afraid,” I told her. “The fact is, I’m finished. God knows how I lasted as long as I did.”

“Anna, stop it. It’s not like you to be so negative about your research. You’ve done wonderful things. You can’t give up because you’ve lost your funding. Researchers lose grants all the time; they just have to get another one.”

“Trouble is, the reviewers’ reports were damning. And they’re right. I was lucky to have the funding rolled over last time. They were probably giving me one last chance to do something new, but I blew it. I simply carried on in the same old way because that’s all I know. I’m a fraud. I’ve always known it deep down, and now I’ve been sprung.” As all this was spewing out of my mouth I could feel myself getting lighter and lighter. I felt hysterical laughter burbling up through my chest, and I poured myself another glass of wine and took a gulp, all the while watching Fran’s face as her expression changed from concern to shock. Then a snort exploded out of me, along with a mouthful of wine, and I put my glass down quickly and grabbed the blue table napkin, mopping the dribbles from my chin and dabbing at the red splotches on the white tablecloth.

Fran’s sweet face split into a grin and she giggled. “You’re drunk. Wicked woman. It’s not funny.”

“It’s definitely not funny, but I’m bloody well not drunk. This is all I’ve had to drink today, and half that’s on the tablecloth.” I wiped my eyes. “Let’s finish this bottle and get another one.” We grinned at each other and then sobered up.

“So what now?” asked Fran.

I looked at her, my mind blank. My pulse was pounding through my whole body. I forced myself to focus. “I suppose I will have to apply for more grants, but you know how long that takes. I don’t think I’ve got much hope of getting anything substantial.”

Fran screwed up her face. I could almost see her neurons flashing as she searched for a miracle.

I tried to ignore the churning in my gut. “I’ll be okay for a while. The good old Medical School Dean said I could have a cubbyhole and a computer for the rest of the year so that I could finish all the papers I’ve still to write.” I swirled the wine around in my glass, and watched the ruby liquid as it came dangerously near to the rim. “Given that boring old basic research is no longer considered worthy, I wonder why I should bother, really.”

“Is he going to pay you?”

“Huh, no hope of that. Although he did say that I might be able to give a few guest lectures, so I suppose I’ll get a few meager dollars for those.”

“Why don’t you go back to clinical practice? You know so much about Huntington’s disease. You’d be a wonderful doctor for them and other neurological patients.”

“Fran, what are you thinking? You of all people know that I’m hopeless at the bedside thing and anything that involves actual patient contact. That’s why I became a researcher.”

“But that was twenty-five years ago. You’ve grown up and changed since then. You might like it now if you gave yourself a chance.”

“I haven’t changed, that’s the problem. I don’t even like socializing with other research staff. You’re the only person in the entire universe who I feel comfortable really talking to.”

“Well you have to do something. What are you going to live on?”

“That’s one of the advantages of being a workaholic with no kids. I’ve got heaps of money stashed away in the bank. Now at last I’ll be able to spend it. Perhaps I’ll fly off to some exotic, tropical paradise and become a recluse.”

“Very amusing. But you could travel. At least for a few months. Go to Europe. It would give you time to refresh your ideas, and then you could write a new grant that would blow those small-minded pen-pushers out of the water.” Fran sounded excited by all these possibilities opening out in front of me.

I could feel my brain shutting down, and shook my head to wake it up. “Perhaps I could take a trip.” I pushed my lips into a grin. “Go and see my mother and her lover in their hideaway. Now there’s a nice tropical island.”

“Doesn’t she live in Shetland? That’s a great idea. You should visit her.”

Fran didn’t always get my sense of humor.

“Fran, it’s practically in the Arctic Circle. I do not want to go there. And right now my mother and her gigolo are the last people I want or need to see.” I rolled my eyes.

“Don’t be unkind. Your mother has a right to happiness, and I think her life sounds very exciting. I thought she was married?”

“She is. And good on her. But she and I are better off living a long way apart.” I yawned. “I can’t think about all this any more tonight. And it’s way past your bedtime; you have to work tomorrow.”

Fran frowned. “I wish you didn’t have to go through all this. It’s horrible. But I know something will come up that’s better. It always does.”

BUT NOT FOR THE NEXT FOUR MONTHS. I CLOSED UP—OR down—the lab, took the team out for a subdued redundancy dinner, and moved into the cubbyhole, where I put my head down and wrote the final report on fifteen years of work. Then I wrote a grant application and sent it off to an obscure private funding body that gave out small grants from a legacy left by some wealthy old woman who died a lonely death from Parkinson’s disease. I had little hope it would be successful, as all I could come up with as a research project was further analysis of the neurological material we had collected over the past few years—hardly cutting-edge research. At least waiting to hear would give me a few months of pathetic hope, rather like buying a ticket in a lottery.

That done, I dutifully went into the university every day and tried to write a paper on a series of experiments that we had completed and analyzed just before the grant was terminated. But my heart wasn’t in it, and I could sit for eight hours with no more than a bad paragraph to show for it.

Boston was hot and I felt stifled. Fran and her family were away on their regular summer break at the Professor’s parents’ cabin on a lake somewhere, and the medical school was as dead as a dodo. I used to begrudge any time spent talking trivia to the researchers in my lab, but now that I didn’t have it, I missed it. Even my once-pleasant apartment had become a prison, clamping me inside its walls the minute I got home in the evenings. I was no stranger to loneliness, but over the past few years I’d polished my strategies to deal with it. I would remind myself that the flip side of loneliness could be worse—a houseful of demanding kids, a husband who expected dinner on the table, a weighty mortgage, irritating in-laws—it became almost a game to see what new horrors I could come up with. You, Anna Fergusson, I’d tell myself sternly, are free of all that. “I’m a liberated woman,” I once shouted, before glancing furtively around in case my madwoman behavior had conjured up a sneering audience. If self-talk didn’t work, or even when it did, more often than not I’d slump down in front of the TV and watch three episodes straight of Morse, or some other BBC detective series, and one night I stayed awake for the entire 238 minutes of Gone with the Wind.

When Fran finally returned from her lake at the beginning of August, I was on the phone to her before she had time to unpack her bags. Understanding as always, she put her other duties aside and the very next day met me at our usual lunch place. She looked fantastic: brown and healthy and young. I felt like a slug. It wasn’t until we were getting up to leave, me to go back to my cubbyhole and Fran to the supermarket, that she remembered.

“Gosh, I almost forgot. Callum was mucking about on the Internet while we were at the lake and came across this advertisement. He made some joke about it being the perfect job for him when he left school, and I remembered how you said after you lost your grant that you should go and live on a tropical island.” Fran scrabbled in her bag and hauled out a scrunched up sheet of paper.

“Fran, for heaven’s sake, you know that was a joke. What is it?” I took the paper she had unscrunched and read the small advertisement surrounded by ads for adventure tourism in Australia.

For rent to a single or couple who want to escape to a tropical paradise. Basic cabin on tiny coral island on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. AUD$250 a week; must agree to stay one year and look after small private campsite (five tents maximum). Starting date October 2008. For more information e-mail lazylad at yahoo.com.au.

I looked at Fran in amazement. “You printed this out for me? I think the sun must have got to you. Lazylad is looking for some young bimbo. And he wants to be paid to look after his campsite. What cheek.”

“That’s what I thought at first, but Callum pointed out that thousands of people would give their eyeteeth for an opportunity like this if the cabin were free. But that’s the beauty of it; you can afford it. And wasn’t your father Australian? You mightn’t even need a visa.”

“Fran, you’re a dear, but can you see me on an island on the other side of the world, singing jolly campfire songs with spaced-out boaties?”

“Have you got a better idea? Or are you just going to continue to fade away in your cubbyhole?”

“No, I’m out of there as soon as I finish this damn paper I’m writing, and then I thought I might try my hand at writing a book.” So there, I felt like adding.

Fran’s face lit up. “A book? That’s fantastic. What sort of a book? A novel?”

I started to laugh. “What happened to you up there at the lake? This is me, Anna. I haven’t suddenly morphed into a normal person. I’m still the same old ivory tower nerd, clueless about people. No, I thought I might be able to write some sort of account of my experiences getting research grants and running a lab. All the highs and lows. Perhaps I’ll discover where I went wrong.” I could hear the gloom in my voice as the words came out of my mouth.

“But that’s a great idea. And you’ll need somewhere to write it.” I could see the mischief in her eyes as she grinned at me.

“I know what you’re thinking, and no, I do not want to live on a desert island at the end of the world.”

“Oh well, worth a try. It wouldn’t hurt to check it out though, would it?”

TWO DAYS LATER I COMPOSED A CAREFUL E-MAIL TO Lazylad, not expecting a reply. Surely the cabin had been snapped up by now if it were such a dream opportunity. I got used to holding my breath as I turned my e-mail on each morning, scrolling rapidly through all the usual stuff looking for Lazylad, telling myself I didn’t care. But the idea of going to Australia had got stuck in my head.

I had all but given up and stopped daydreaming about writing a book on a deck looking through the palms across an azure blue ocean, when there it was—a reply from Lazylad, who I later found out was actually called Jeff.

Thanks for e-mail. Been away sorry for delay in reply. Cabin still available if you want it. Photos attached. Island called Turtle Island (after the sea turtles here) and is a coral cay just above Tropic of Capricorn about eight hectares in area with a large reef surrounding it. A few eccentric people own houses here and that’s about it apart from my small campsite. Only transport is fishing boat or charter. Cabin basic but comfortable, everything included. Solar hot water (roof water) and solar power for lights and computer, gas fridge and stove, no telephone. Satellite broadband from some locals’ houses you can use occasionally in return for a few beers. One of the local fishermen brings supplies over about once a fortnight in his boat and locals can hitch a ride for a small fee or more beers. Fantastic snorkeling and diving, birds, turtles, etc. Weather always perfect (almost). If you are interested e-mail me your phone number and I’ll call you when next on mainland to chat. Looking after campsite is a doddle. First come, first served (no bookings), take their money, and make sure the old guy on the island does his job of emptying the toilet and the rubbish bins. It would be good to get someone here before I leave for UK on 18th October so I can show you the ropes.

When I scrolled down so I could see the photos my hand was trembling. The first one showed a rectangular wooden building with what appeared to be an open front with a wide deck. A big wooden table and a few white plastic chairs, along with a heap of what looked like diving stuff—a wetsuit and flippers and a tank—sat on the deck. In the dimness of the inside I could make out a bed on one side of a partition and what looked like a kitchen on the other. The cabin was surrounded on three sides by trees with large leaves, and in front of the cabin was a sweep of white sand. The sand had something black on it, and when I zoomed in I could see it was a cluster of three large black birds just sitting there. The second photo showed a narrow strip of white sand, fringed by trees with feathery-looking leaves, and then the truly azure blue sea and sky. The last photo was like something on a travel brochure: a tiny, oval, flat island with green vegetation crowning the center and white sand around the edge, surrounded by blue. In the blue I could see dark patterns, the coral. I grabbed my pendant and brought it to my mouth. The last time I had seen coral sea had been when I was twelve years old, and I had thought then that I never wanted to see it again.