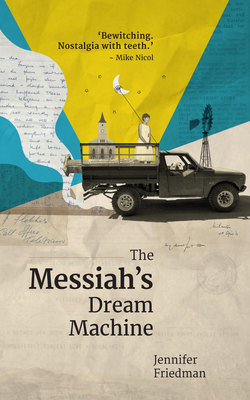

Читать книгу The Messiah's Dream Machine - Jennifer Friedman - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1.

ОглавлениеThe way things used to be

The circus is back in town, and all the wild and familiar sounds of the night have disappeared – overwhelmed and drowned by its strange noises and feral smells. Across the bridge, the distant crash and roll of cymbals and drums collide in the dark with the stamping shadows of elephants, and the air shakes with the rumbling roars and coughs of lions pacing their cages on huge bunched paws, testing the steel bars with their heads held low, manes fanned yellow against their backs. When the circus comes to town, the air is fevered and restless, and all the dogs howl and whimper and whine.

The circus is the highlight in the calendar of each year; a social event important to our sense of belonging in this place where everyone knows everyone else. Like Christmas every summer, the circus never fails to return.

Ma stands at my bedroom door.

“Would you like to go to the circus tonight?” she asks.

I shake my head. I feel lost, as if I’m already a stranger peering through a closed and latched window at all the familiar places in my life, the people I know and love. Tomorrow, a train will take me to a school in a city far away from my home, from Sandy-my-dog and Marta. From Isak, and all my friends.

I don’t want to go.

Ma thinks I don’t know, but I watch, and I listen. I know why she’s sending me away. In our house, Ma’s the boss. No one challenges her, only me, and she doesn’t like it.

I sit on my bed and hug my knees, remember how it used to be.

Entertainment for the masses

The circus comes every year, and everyone in town dresses up to see it.

“Entertainment for the masses.” Pa sniffs.

But even Pa’s prepared to join the masses sometimes, and Ma says I can wear my party dress. We stand, impatient, in a long line of excitement in the warm, dusky air. Pa and Ma say hello to everyone, and everyone says hello back to them, and the red dust rises under our feet, and the great white circus tent fills the sky. The air smells fierce. My nose pricks with sawdust and manure and candyfloss, and animals that stalk about their cages in the dark. It smells of sweat and hairspray, greasy makeup, the stink of grubby costumes on the bodies of the heavy-thighed, silver-sequinned performers.

I’m five, or eight, or ten years old, sitting on the hard edge of a wooden bench in the front row next to my sisters and Ma and Pa. It’s hot. The air in the tent hums with noise and dust and cigarette smoke. My eyes burn with excitement. The bright lights dim, and the drums roll, trumpets blare and the cymbals crash, and the heavy red-and-gold curtains draw apart, and captured in a cone of sharp and perfect light, cracking his long whip, the ringmaster strides into the centre of the ring. Clowns in polka-dotted bowler hats stagger over their wide pants, the toes of their shoes slapping the floor in front of them. They wobble and teeter about on silly bikes with tiny wheels, plastic horns blaring as they tumble head-over-heels through the dusty haze. The clowns’ faces are painted white, their lips drawn thick and red. They smile and smile, run about on bowed, stumpy legs offering bunches of plastic flowers to the ladies in the audience, and when the ladies reach to take them, the flowers squirt water like magic into their faces, and everyone laughs, except the women whose faces are wet.

A bareback rider in a sparkly silver costume and black fishnet stockings rides into the ring on a white horse. When she does a backflip, the legs of her costume pull right up, and her bottom hangs out, and all the men in their suits and ties – even Pa – laugh and leer and clap, but when I look around, all the ladies’ faces are stern, and their lips are sucked right in.

A lady contortionist turns herself inside out. Three little dogs are dressed in pretty party dresses like me. They beg, do tricks, dance daintily on their hind legs. I’ve tried to teach Sandy to do tricks too, but he won’t listen. Then the lights go out, and all the people gasp in the dark. We hold our breath, and in the hushed tent we crane our heads, look up, and in the light of a single spotlight high above us, see a trapeze artist hang and twirl in her tiny silver tutu like some exotic bird while far down on the ground below, we are fixed to our seats, our arms held out as if we could catch her if she should fall.

Then the glittering tutu slides down a long, long rope, and the ring is filled with light. A kettledrum rolls. A trumpet blares triumphant. The red velvet curtains open, and there, high on the wrinkled grey neck of an enormous elephant sits a lady dressed in a dazzling yellow costume. Another elephant, and then another and another, their trunks curled and loving around each other’s tails, follow in a solemn procession. Triangles of red velvet lie on their heads, and tassels of gold sway down to their trunks. The elephant with the lady on its neck walks into the centre of the ring. The lady stands up, she climbs right on top of its head. The yellow costume looks small and very far away. I can just see her lips move. The elephant raises its thick trunk, and everyone breathes deep as it snakes around the lady’s middle. Held fast in its grey coil, she raises her arms and points her toes like an exquisite ballerina, and then she’s lifted high into the air and placed ever so gently on the ground in front of us. The enormous elephant walks backwards and plops its wobbling backside down on a small, red-and-white striped, flat-topped cone while the others do handstands. The pretty lady in her yellow costume strokes each one on its trunk. The crowd whistles and claps, tosses peanuts and popcorn into the ring, and far away, I’m sure I can hear Marta shout, “Hau!” I peer hard into the dark to see if I can catch a glimpse of her, and I wave, just in case. I love Marta. She looks after me. She used to help Ma in the house before I was even born. Now she comes to wash our clothes and iron them.

Once, when the circus was in town, everyone came to watch the elephant trainer lead two big elephants up a ramp onto the back of one of the Thornton’s Transport lorries. Pa took a picture, so everyone could see how strong the lorry was, what a heavy load it could carry. It was for an advertisement. In the photograph, the lorry looks just like the ones that take the giant reels of wire to the gold mines. When the reels roll onto the lorries’ steel beds, it sounds like thunder rumbling through our town.

All the men in the circus wear long pants and long-sleeved shirts. The women wear fishnet tights under tiny glittering costumes decorated with frills and spangles. Close up, their thick makeup makes them look scary and strange. The men in the audience are dressed in suits, white shirts, and ties. They wear hats and smoke cigarettes. The women are in their almost-Sunday best, their second-smartest hats and gloves.

The most exciting and scariest circus act of all comes after the interval and the bags of popcorn and peanuts and ice-creams, and – best of all – the clouds of sticky candyfloss on long sticks. That’s when the circus workers bolt a cage of thick iron bars around the inside of the ring. Through the open curtains, we can see a long tunnel of steel hoops. When the cage has been bolted firmly into place, a man in a suit of fiery red-and-gold walks around the ring, shaking each bar to test it. He strides out, and the curtains close behind him. Then, the cymbals crash, and the drums roll, and between the steel bars of the tunnel we glimpse the flash of yellow fangs, the glare of yellow eyes, of ears laid flat, and thick, shaggy manes bristling on muscled shoulders. The lions grumble. Show their curved teeth. The red-and-gold uniform flashes. The whip cracks, and the whole town – black and brown and white – unites in one long-held breath. The crowd roars, and somewhere a woman screams, but no one turns around. My eyes are wide and staring. The lions crouch, snarling on flat-topped cones. Loose hairs from their manes drift like dust motes in the light. They reach out their heavy paws to swat and swipe at the brave lion tamer, but each time, he dances away. Their menace rumbles across the tent, and in the dark behind the bright ring, they sound like Pa when he’s cross with me. When the lions run back through the steel hoops to their cages, the lion tamer’s smile under his bushy black moustache is white with relief. I jump off my hard seat, clap my hands and laugh, and when I turn around to look at Ma and Pa, they’re laughing too.

Sitting in the back seat of the car on the way home, I lean against the door and stare into the dark beyond the glow of the streetlights.

“Is everything in the circus real, Ma?”

In the front, next to Pa, she half-turns back towards me.

“What d’you think, love?”

Her teeth shine in a smile. Pa grunts. My sister nods, half-asleep in her corner.

I’m only five, or eight, or ten years old. I shake my head. The back of Pa’s neck is stiff.