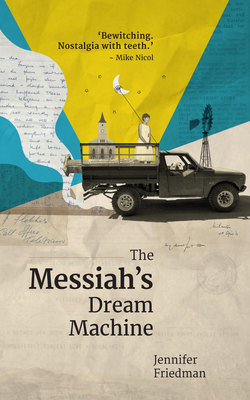

Читать книгу The Messiah's Dream Machine - Jennifer Friedman - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5.

ОглавлениеJourneys

“Gemsbokstasie”

“Dwykasloot”

Wit staan die gras van Karoo.

Leeg blink die myle,

slinger brakmaer die kranskopberge deur

waar maer windmeulens

pluk

aan ’n smal wind

wat waai.

(Jennifer Friedman, Gedigte – Standpunte 153)

For two days, I watch the open plains of the Free State roll by. The hills are crowned with rock, garlanded with red and gold. Above the edge of the shimmering horizon, the shadows of trees dance in the heat. Eagles and hawks hang in the sweep of the sky. The land slides into a distant, watery tremble. It feels as if I’m watching it from some place in the past; as if the future has already happened; the present, come and gone, and all I see is the tail end of it as the land unravels in reverse.

I open my window and hold my arms out to the rushing air. Ma’s dozing in the corner of her seat. She jerks awake and reaches out as if to catch me.

“Sit down,” she blurts, blinking her eyes. “What’re you doing, you silly girl? You’ll fall out!”

I put my hands on the window rail, lean forward just a little, and feel the pull and tug of the Free State veld.

You can’t go, you are mine, click the wheels on the tracks.

I stumble down the rocking corridor towards the tiny lavatory at the end of the carriage. A man in a shiny blue shirt turns to look at me. His elbows are spread on the railing in front of a window, his bottom pushed out against the wall behind. I see his face, red and sweaty, his hair is lank and greasy in the heat. I look away, down to the end of the corridor.

“Excuse me, please.”

He straightens, wipes his hands against the sides of his trousers, licks his lips and leers at me before moving into the middle of the corridor. “First give us a kiss, girlie.”

“Voetsek!” I scream, and try to push past, but he grabs hold of my arm and pulls me towards him.

“Los my uit, jou vark!” I scream and slam my fist into the slack fat of his stomach. He doubles over and lets me go. I can feel my heart hammering behind my eyes. I lunge past him and slam the toilet door behind me. In the open lavatory pan, the grey gravel between the train tracks streaks past as the train steams on. I’m afraid to sit down, afraid to open the door. When I finally wrench it open, the corridor’s empty. I run. The train leans into a bend. I grab at the railing under a window. When I look back, the long narrow space behind me is empty. I don’t tell Ma. She’ll just get cross and call the conductor. I don’t want anyone to know.

We puff and sway past saltpans and thorn trees, red grass and khaki bush, cement dams and windmills standing sentry against the sky. The train thunders past pepper trees, corrugated-iron water tanks rusting behind redbrick railway houses with wood smoke idling from their chimneys. Chickens scatter, roosters crow. Dogs pant in the shade of tall bluegum trees. The train tracks flash like jackal eyes in the night. I lay my arms flat on the windowsill and see the Karoo miles twist and turn, endless across the dry flat land. Far away across the plains, the hills wear cliffs of gold and brown. I write a poem.

The light filters slowly through the dust before it sinks away in the dark. The night is pricked with stars, and the land is turned to shadows. The train clicks and sways, rocks me to sleep like a lullaby. In the morning, I pull up the blind and open my window. Ma’s still asleep, her face turned to the wall. A thin morning breeze washes the sky with light. The train moves slow and steady and, in a brief absence of sound, the timid tin-tin-tinkie of grey-backed cisticolas rises from the thick, thorny scrub.