Читать книгу Women in the Shadows - Jennifer Goodlander - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

GENDER, PUPPETS, AND TRADITION

If in the contest of colonial production, the subaltern has no history and cannot speak, the subaltern as female is even more deeply in shadow.

—Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (1999, 274)

When I arrived at the house of my teacher, I Wayan Tunjung, a well-known dalang, or puppeteer, on the evening of January 17, 2009, it was already dark, even though it was just past seven. I was invited to accompany Pak Tunjung1 to a shadow puppet, or wayang kulit, performance in Mas, a small village in southern Bali. Wayang kulit functions as a sacred ritual that mingles with religion and custom, as well as a social event with prescribed roles for all participants. Each performance is different, but I offer this description in order to give an example of the form and context of the tradition of wayang kulit.

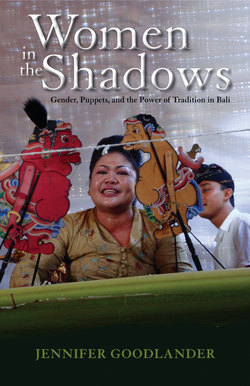

I rode my sepeda motor, or motorbike, to Pak Tunjung’s family compound. As always, when I went to a performance with Pak Tunjung, I wore pakian adat, the traditional clothing that, for a woman in Bali, means a sarong and a brightly colored kebaya—a type of blouse of lace or cotton with lace decoration. Around my waist I wore a sash of a contrasting color (fig. 1.1). Pakian adat—required for any temple ceremony, ritual, or important event in Bali—marks the performance as “special,” or tied to traditional values and practices. Like all Balinese wearing this type of traditional clothing, I did not wear a helmet while on the motorbike, because the Balinese feel that a helmet is too modern and, as many Balinese explained to me, looks “wrong.” My Balinese friends claimed that the law reflects this attitude by not requiring cyclists to wear a helmet with pakian adat; thus, at least discursively (if not actually), a separation between modernity and tradition is marked within both the social and the legal spheres.2

Figure 1.1. This sign explains the requirements for traditional clothes (pakian adat) for men and women in Bali. Photo by author.

As I entered through the gate to the main courtyard of the compound, I was invited by Pak Tunjung to sit with him so we could talk about the performance he was going to give that evening. He contemplated which story to tell, explaining that a dalang knows many stories and must select the appropriate one for each situation. The performance that night was going to be at a family’s compound for a tooth-filing ceremony, often called matatah in Balinese, or potong gigi in Indonesian, which is a coming-of-age ceremony in Bali (Eiseman 1989, 108–14). Wayang kulit provides entertainment while serving as a necessary ritual for many such ceremonies in Bali. The performance also operates as a marker of material wealth and power, because not every family can afford to hire a wayang kulit troupe for its personal rituals.

After Pak Tunjung and I chatted for about half an hour, the four musicians and two assistants, all men, arrived and began preparing for the performance. Even though the dalang is the spiritual and performative center of wayang kulit, he does not perform alone. The assistants carried the four musical instruments called gender wayang, the oil lamp, sound system, the box containing the puppets, and other equipment to the truck waiting outside the compound gate. Pak Tunjung checked his puppets earlier in the day to make sure he had the ones needed for the performance arranged within the puppet box. As the assistants were gathering the equipment, Pak Tunjung told them that he needed the crocodile puppet I had used earlier in the day for my lesson. One of the musicians took it from the puppet box I used for rehearsal and carefully placed the crocodile puppet in the box Pak Tunjung was going to use for the performance. Finally, Pak Tunjung went to bathe and get dressed. He had prayed and given offerings in his family temple earlier in the evening in order to recognize the gods and to ask for a successful performance. Pak Tunjung explained that the gods would guide his performance and provide protection from any troublesome spirits, or ilmu penengen (lit., black magic).3 At around eight o’clock we piled into the van and headed on our way. I sat in the middle of the crowded front seat with the driver and Pak Tunjung, while the musicians, additional assistants, puppets, and equipment rode in the back. The location for this performance was only about ten minutes away, but sometimes Pak Tunjung would travel an hour or more to perform.

We climbed out after the truck pulled up in front of the family compound where the ceremony and performance were being held. I could hear the sound of a river running along the side of the narrow road. The men unpacked the vehicle while I followed Pak Tunjung through the gate that led into the compound. Once inside, a man came over to greet us and led us over to a bale, or covered platform, and we were asked to sit on a blue carpet. Soon, a man in a sarong and a mismatched batik shirt came over. He was a good friend of Pak Tunjung and they were happy to see each other. Later Pak Tunjung explained that since having his own family—a wife and a son—it was much harder to visit friends. When he was younger, Pak Tunjung would travel all night to give performances, often giving two or three in one evening, almost every night of the week. After his son was born, in 2006, he performed less often and preferred to stay closer to home. Often Pak Tunjung decided to accept a performance opportunity because it allowed him to see people he knew, exchange local gossip, and visit old acquaintances. Likewise, for many in attendance the performance provided an excuse to socialize, gossip, and eat together.

Social hierarchy is performed through language and actions4 in Balinese society, and traveling with Pak Tunjung provided me with an opportunity to observe and participate in these exchanges. We hadn’t been sitting long before several women approached and offered us coffee and jaja, little Balinese cakes made of rice and palm sugar. Pak Tunjung and I were provided with small individual trays with coffee and two cakes each, whereas the musicians and assistants shared one large common tray that had many coffees and cakes. The women smiled at me and said, “Silakan makan, silakan minum” (Please eat, please drink), as they set down the trays and hurried back to the kitchen area. Another tray was brought with cigarettes. One of the musicians gestured to the tray and made a joke of offering them to me with a smile, since it is not considered appropriate for a Balinese woman to smoke. They all laughed and grinned their approval when I refused the cigarettes. I waited to eat or drink until Pak Tunjung indicated that it was appropriate for me to do so. He ate and drank very little that night, and I remembered earlier he mentioned that his stomach was upset and he was worried about making it through the performance. Afterward he remarked to me that during the show he did not think about his stomach but only focused on telling the story and manipulating the puppets, attesting to how physically and mentally demanding the performance is for the dalang. Within the performance sphere, the dalang rises to the top of the social hierarchy: he is treated as an honored guest, he is valued for his wisdom and ability to perform, and he relaxes at the center of the compound, in a seat of honor while others prepare for the performance. My own presence at the event served as an interruption to the usual social hierarchy playing out through and around the performance. Unlike other women there, I did not help out in the kitchen or with serving. Like the other assistants, I was offered cigarettes, but my own refusal to take one pointed back to my womanliness. Like women dalang, I was disrupting the “usual” ways of doing things, but everyone made an effort to negotiate those boundaries in compliance with traditional social structures.

At approximately half past nine, we moved over to the compound’s central bale, where the screen for the performance was assembled next to an elaborate altar with many colorful decorations and offerings. Behind the screen on a chain hung the oil lamp, and the puppet box and musical instruments were set in their places on the floor directly behind the screen. It was not a very large platform and I had to perch off to the side, next to the musicians. Several young boys and adults gathered around behind the screen to watch the dalang place the puppets, but in Bali most of the audience watches from the shadow side.5 Figure 1.2 shows what it looks like behind the screen for a typical wayang kulit performance.

During the performance there are many things going on at once; rarely do people sit and observe with focused attention the way an audience would in the United States.6 A group of young boys watched the beginning as the puppets were taken out of the box, but once the characters began talking, most of them wandered away. I could hear the sound of a video game being played nearby and it occurred to me that the beeping electronic music of the modern game made an odd contrast to the music and dialogue of the traditional puppet show. Scholars, visitors, and Balinese alike often wonder if wayang kulit will be able to compete with other more technically advance modes of entertainment. These modern activities point to how traditional performance in Bali is changing and demonstrate how it also remains the same in many ways. The women were also missing from those watching the performance; they hardly had time to sit still, since they were working in the kitchen or adjusting the offerings. Old men were the most attentive audience members, and they sat in front of the screen on the ground and chewed betel nut as they watched. At one time or another, every person attending the event was drawn toward the screen like moths to a lightbulb. A group of younger men sat off to the side loudly talking and drinking tea during the performance; sometimes children would even run up and touch the screen or play with the puppets; women would stop in their tracks and take a moment to watch before rushing to the kitchen or family temple. It is never quiet during a wayang kulit performance.

Figure 1.2. Backstage during a wayang kulit performance. Photo by author.

Some parts of the performance attract the attention of a larger crowd of people. Sangut and Delem, two of the main clown puppet characters, or penasar, performed a scene full of jokes and slapstick that was one of the highlights of the performance. During the scene Delem described a recent experience he had going to the hospital and all the troubles he had there. The dalang used the comedy of the penasar to critique the troubled Indonesian medical system for being both expensive and inefficient. The audience’s chatter erupted into laughter and cheers in response to the joking of the clowns. At one point everyone burst into applause at a clever remark made by Delem. The final scene of a performance is typically a fight scene with loud music and a great deal of action and can last up to an hour. Sometimes the puppets battle hand to hand and throw each other across the screen, and other times the puppets use arrows or other large weapons. As wayang kulit struggles to please a contemporary audience familiar with faster-paced movies and television, the comic and fighting scenes often dominate the performance over conventional themes of religion and moral philosophy.

After almost three hours of performance, the kayonan, or tree of life puppet, was returned to the center of the screen and the musicians played one last melody as Pak Tunjung and his assistants returned the puppets to the box. There was no applause, the audience just wandered away as soon as the penasar characters returned to make some final comments about the lessons that could be learned from the story told that night. Offerings were brought so that the dalang could bless the screen, the puppets, and the musical instruments by sprinkling holy water. Ritual significance permeates the performance and gives the dalang much of his power. At the end of the short ceremony, Pak Tunjung pulled out the center pin rooting the screen to the banana log to signify the end of the performance, and then he went off to the side to sit and talk with the sponsors of the performance. The musicians and the assistants folded the screen, gathered the sound equipment, and loaded everything into the van.

The work of the dalang is not over when the theatrical portion concludes. The sponsors thanked Pak Tunjung for the performance and gave him a small basket that contained several brightly colored flowers, rice, and money. Pak Tunjung counted the money, put it in his pocket, and tucked a yellow flower from the basket behind his ear. He often gave a small portion of the money back to the sponsor. This type of reciprocal exchange can be understood to reposition power from the sponsor to the dalang. Following a few more minutes of conversation, Pak Tunjung begged, “Permisi, mau pulang. Tamu saya capai” (Excuse us, we need to go home. The guest I brought is tired). Just as I benefited from traveling with Pak Tunjung, he often called attention to my presence to mark his performance as important on a global scale. We then stood, found our shoes, and returned to the van. Upon returning to Pak Tunjung’s house, the assistants unloaded everything from the vehicle. I tried to help but they laughed at my efforts to carry the heavy equipment; it is not a job for a woman. As the final load was carried through the gate, I got on my motorbike to leave. Pak Tunjung reminded me, as he always did, to drive slowly and safely. Before going to bed, Pak Tunjung gave the puppets additional offerings and prayed to thank the gods for the successful performance.

Through my friendship with Pak Tunjung I was offered a privileged window into the world of Balinese culture; attending performances such as this one allowed me to witness firsthand the different components that constituted the tradition of wayang kulit, an opportunity complemented by my own practice of the art form. The many elements of the event—the people in the audience, the rituals that surround it, and the content of the story—all come together in a complicated tangle of tradition and modernity, gender, and performance.

The term tradition suggests an object or practice that has come, unchanged, from some mythical past into the present. Wayang kulit, or shadow puppetry, is often considered one of the oldest and most important traditions in Bali because it connects a mythic past to the present through public ritual performance. Flat, two-dimensional puppets, made out of carved leather, are manipulated against a screen by a single puppeteer to tell stories from the Mahabharata, Ramayana, or other Balinese myths and histories. These entertaining performances are generally given as an integral part of a ceremony or ritual. The dalang, or puppeteer, is the central figure in this performance genre and is revered in Balinese society as a teacher and spiritual leader.

Until recently, the dalang was always male, but now women in Bali are studying and performing as dalang. This innovation comes not without controversy because many people in Balinese society question women’s ability to undertake the difficult physical and spiritual tasks of performing wayang kulit, as well as the appropriateness of a woman performing it. Women are rarely present in the audience or represented on the screen, thus making my interest in women dalang an anomaly among most considerations of wayang kulit. Women’s roles in Balinese society have traditionally been in the sphere of the home, or in the shadows, and the opportunity presented within the shadows of wayang kulit offers an occasion to analyze how traditional performance creates and maintains systems of power in Balinese society.

Tradition is regulated by time and place; local, national, and international forces all contribute to the meaning and practice of traditions. Bali is a small island, located just east of Java and slightly south of the equator. Bali is part of Indonesia, which is made up of over seventeen thousand islands with over three hundred distinct ethnic groups and as many languages. Bali is less than one-third of 1 percent of Indonesia’s land area of nearly 700,000 square miles (1.8 million km2), yet it is Indonesia’s most popular destination. It has a tropical climate with a lush volcanic landscape in the south, dotted by terraced rice fields, and in parts of the west and east it is dry desert. Bali is one of Indonesia’s most populous areas, with a population of over three million people, compared to the population of Indonesia, as of 2016, at almost 260 million. Tourism is the major source of economic revenue on the island, but historically people on Bali made their money through rice and trade (Pringle 2004, 1–5). Bali is the most visited and often the most recognizable part of Indonesia to foreigners.

Society in Bali is anything but homogeneous, as my use of the terms Balinese society or the Balinese may imply. Instead, when I use these terms, I am referring primarily to those who identify as Hindu, are ethnically Balinese, and live in the southern part of the island, where my research was conducted. I use the terms in order to both preserve clarity and put my work into conversation with other scholars writing about “the Balinese”; even so, I want to foreground this term as a conscious discursive construct rather than to erase the diversity of the people living on the island of Bali (Barth 1993, 9–15).

Scholars who write about women’s performance in Bali often posit that women performers challenge Balinese tradition by taking nontraditional roles without accounting for how “tradition”7 functions as a complex principle within Balinese arts and society. Catherine Diamond’s work resonates with that of other women scholars (Bakan 1998; Susilo 2003; Palermo 2009; Downing 2010) by pointing to gamelan wanita, or women’s gamelan, as one of several performance genres giving evidence of women’s expanding gender roles in Bali. Middle-aged women especially find a “sense of accomplishment distinct from their other duties that are usually both never ending and taken for granted. Performance provides an opportunity to dress up, be involved, and sparkle artistically. It has raised their self-esteem, giving them an individual public identity other than being someone’s wife or mother” (Diamond 2008, 235). Diamond, like the others, acknowledges limitations—in the end, art forms created and populated by mostly male performers perhaps can offer only partial opportunities for women to find their voice, and that until women create their own forms and characters they will experience only minimal representation (264). Cok Sawitri, a Balinese performance artist who borrows from tradition yet freely creates new and contemporary performance, is cited as an example of a woman managing to break gender norms through experimenting with new modes of performance (Vourloumis 2010; Diamond 2008). Even so, the very nature of this kind of work places Sawitri at the margins, and her work has limited efficacy.

Inspired by these other publications on women and Balinese performance, I began my own study hoping to find that women performing as dalang would show a real departure from gender norms and indicate that the goal of equality was within reach. Instead, I found that women dalang have had little lasting impact on social hierarchy in Bali—and women dalang rarely, if ever, presently perform. I realized that in order to understand women dalang in Bali, and my own experience training as a dalang, I needed to better understand the notion of tradition in relation to gender and performance within Balinese society.

The idea of tradition in Bali is taken for granted as something from the distant and mythic past that functions as an important marker of identity and culture. Practices and things are designated as important because they are part of tradition. I approach the idea of tradition as both a taxonomic category and a cultural system to offer a richer, more complicated understanding of tradition in relation to gender in Balinese society as constituted within theatrical performance. In my analysis, the notion of tradition is used in relation to three different, yet overlapping, fields: the construction of Bali as a traditional society, the role of women in Bali as being governed by tradition, and the performing arts as both traditional and as a conduit for tradition. My focus is on Bali, but Balinese tradition exists within the nation of Indonesia, which also contributes to discourses and social meanings regarding gender and performance. I argue that the Balinese conception of tradition is not embedded in choreography or story, nor is it an object like a puppet, but rather tradition is a sign of power in the Balinese context through the meaning that society ascribes to those activities and objects. Therefore the concept of tradition in Bali must be understood as a system of power that is inextricably linked to gender hierarchy. The phenomenon of women dalang allows me to interrogate the complex dynamics of power in Balinese culture that are expressed through the performing arts. My analysis draws upon my own experience of the practical training and ritual initiation to become a dalang, coupled with interviews of early women dalang and leading Balinese artists and intellectuals. I unpack notions of tradition and gender as they relate to wayang kulit through examining practice, material objects, and ritual as they relate to systems of power.

Power as a concept in Indonesian society differs from how power is conceived in most Western cultures. Benedict Anderson, in his exploration of Javanese systems of power, provides a useful definition that applies equally well in the Balinese context. Anderson describes “power as something concrete, homogeneous, constant in total quantity, and without inherent moral implications as such” (1990, 23). This is in contrast to Western definitions, which see power as “an abstraction deduced from observed patterns of social interaction; it is believed to derive from heterogeneous sources; it is in no way self-limiting; and it is morally ambiguous” (22). In Bali, evidenced in wayang kulit, Anderson’s notion of power permeates the aesthetics, performance, and social context of the performance—power is valued by its accumulation rather than its use. Shelly Errington (1990, 3–5) explains that this different system of power has made it difficult for scholars to understand gender relations in Southeast Asia because the systems of gender are not recognizable by Western standards. For example, in Bali both men and women wear sarong but they are not tied the same way. This difference is difficult to identify and understand without being able to “read” the social symbols. Wayang kulit provides a space to examine social systems of gender and power as they relate to tradition in Bali.

This book is divided into two parts in order to reflect the primary division of Balinese cosmology between the visible realm, or sekala, and the invisible realm, niskala. The first part—Sekala: The Visible Realm provides a detailed overview of the practices and objects of wayang kulit that emphasize the changing nature of the tradition. Chapter 2 examines the process of becoming a dalang by focusing on my own study of performing wayang kulit in order to establish the social nature of tradition as practiced within the performance. Folklorist Barry McDonald proposes that tradition is “the human potential that involves personal relationship, shared practices, and a commitment to the continuity of both the practices and the particular emotional/spiritual relationship that nourishes them” (1997, 60). Building on this definition and drawing on the work of Pierre Bourdieu, I analyze my own experience of studying this art for more than a year in Bali in order to frame wayang kulit as a practice that reflects the dynamic social and cultural dimensions of the performance and of the concept “tradition.”

Chapter 3 builds on this work and describes and analyzes the objects that are required for a wayang kulit performance, such as the puppets, the puppet box, and musical instruments, together with the less tangible objects (i.e., skills), important for a performance such as the voice, the music, and the stories told. Throughout the chapter, I emphasize how these objects function as material culture that relates to economic and social capital. For example, I examine the puppet box as one of the most important markers of a dalang, discuss my own process acquiring a box, the criteria for determining its quality, and how frequent use is an important part of its value as a traditional object.

The second part of the book—Niskala: The Invisible Realm—examines the many invisible realms of power expressed through and beyond the performance of wayang kulit. Chapter 4 begins with my invitation to perform wayang kulit at the Ubud Festival in August 2009. Thus my role changes from being a student and researcher to becoming a dalang and details the transformative spiritual process I underwent. I describe the rituals and ceremonies necessary to give a performance and also problematize the relationship of identity and spirituality in Bali in regard to tradition and power as I, a foreigner and a woman, begin to occupy this unique position in Balinese society.

Chapter 5 examines how the recent phenomenon of women dalang manipulates invisible realms of ritual and social power through the tradition of wayang kulit. I examine relationships between government institutions and ritual performance in order to contextualize the practice of women dalang within the greater arena of gender relations and traditional performance, especially as these relate to national agendas of modernization. I look closely at the initial opportunity for women to study wayang kulit made by I Nyoman Sumandhi, the then head of the Balinese performing-arts high school. The chapter contains interviews with Pak Sumandhi and five of the most prominent women dalang to perform in Bali.

The final chapter examines a new performance I learned that tells the story of Gugur Niwatakwaca. This story features several female characters and offers an opportunity to put gender in conversation with the invisible and visible realms of wayang kulit to better understand how women dalang point to gender in Balinese society into the future.