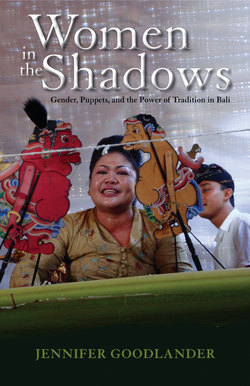

Читать книгу Women in the Shadows - Jennifer Goodlander - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

PRACTICES OF TRADITION

Art cannot be taught. To possess an art means to possess talent. That is something one has or has not. You can develop it by hard work, but to create a talent is impossible.

—Richard Boleslavsky 2005, 1

The Tradition of Wayang Kulit

The practice and significance of Balinese performance constantly changes over time. I Made Bandem and Fredrik Eugene deBoer (1995) describe how variance and innovation flourished in the twentieth century with the professionalization of performers, influences from foreign artists and audiences, expanding tourism, the formation of the nation, and the natural creativity of Balinese artists. Some forms become popular and remain as new “traditions,” while others may exist for only a brief moment. In Bali, art forms exist and move along a dynamic scale between religious and secular, or kaja and kelod (indicating the mountain and the sea respectively). Constant adjustments within arts reflect Balinese cosmology, which favors balance and harmony, or rwa bhineda. The relationship is circular—“while the performing arts themselves are also subject to social change, acts of performance are simultaneously employed to further the understanding of what constitutes harmony in the modern world as well as restore it” (Diamond 2012, 92). Tradition changes to mirror a continuously evolving society.

Since the start of the twenty-first century, the idea of tradition has undergone several notable changes in Bali. Tradition as vital to Balinese societal well-being came sharply into focus after the bombings in a Kuta nightclub on October 12, 2002. Many writing for the press and within the government felt that the Balinese had suffered this calamity because they had wandered too far from traditional values, religion, and culture and that in order to both heal and move forward the Balinese must look to the past. This return to the past has been dubbed ajeg,1 a word that is difficult to translate directly, but now the emphasis on balanced harmony stresses stasis rather than fluid change. Ajeg Bali has been invoked in order to justify architectural styles, religious imperatives, gender relations, political movements, and recently the term is used in discriminatory actions against the large number of immigrants from other parts of Indonesia who are looking to share in Bali’s thriving economy. Ajeg is not so much a longing to return to the past but rather a desire for stability in an era of rapid change. Tradition, then, becomes a litmus test for and marker of that stability. Of course, not all Balinese subscribe to the ajeg Bali doctrine, and I did not directly encounter the term in relation to wayang kulit during the course of my research. However, it is necessary to mention it here as part of a larger conversation within Balinese society as it struggles to maintain unique identity and values against many different forces including tourism, Indonesian nationalism, globalization, and modernization.

Traditional performance provides the Balinese a means for situating themselves in relationship to the world. Performance is often synonymous with culture in Bali. Angela Hobart offers the typical view of wayang kulit as tradition:

It is the most esteemed and conservative theatre form and hence its dramatic and aesthetic principles link it to other dance-dramas, statues, reliefs, and traditional painting. Of these the shadow play is regarded as the original form. Through these various manifestations the villager is able to probe and analyze his assumptions of self, in a world which is increasingly affected by modern trends, while retaining his human dignity. (1987, 14–15)

In practice, wayang kulit as tradition means that each performance follows certain conventions and structures.2 At night, Balinese wayang kulit is performed against a screen made of white cloth that measures about six feet across and is outlined in a red or black border.3 The dalang, or puppeteer, brings his own screen to the performance area, where the sponsoring family or village has either constructed a booth or erected a stage for the performance (fig. 2.1), and a frame is built out of bamboo for the dalang to affix his screen and hang his lamp. The dalang sticks his puppets into or leans them against the banana logs along the bottom and sides of the stage. Although electricity is sometimes used, an oil lamp that hangs right in front of the dalang’s face is still the preferred method of illumination. A microphone now is commonly affixed to the lamp to amplify the dalang’s voice. Four gender wayang, small metallophones, typically accompany the performance, although some genres of wayang will use a larger gamelan ensemble. Musicians and assistants sit behind and to the side of the dalang while most of the audience watches the shadows projected onto the other side of the screen. Each of these elements is symbolic: the screen is the world; the puppets are all the physical and spiritual things that exist in that world; the banana log is the earth; the lamp is the sun—it allows there to be day and night; the music represents harmony and the interrelationships of all things in the universe; and the dalang, invisible behind the screen, resembles a god presiding over everything (Hobart 1987, 128–29).

Figure 2.1. The assistant hangs the screen in preparation for a wayang kulit performance. Photo by author.

Wayang kulit is often described by other scholars, as well as many of the Balinese I met, as a microcosm of Balinese society, culture, and ideals, because a wayang kulit performance instructs its audience on matters of morality, politics, and philosophy. Wayang kulit also functions as a form of offering to the gods. Balinese Hinduism divides the world into three parts: the lower realm of “bad” spirits, or demons; the middle realm that we live in; and the upper realm of the “good” spirits, or gods (Lansing 1983, 52). Balinese cosmology does not privilege gods over demons in the same way Christianity does, because there is no struggle for one side to eventually win out over the other. Instead there is a recognition of the importance of both kinds of power; much of Balinese religious activity, including wayang kulit, is centered on bringing these opposing forces into balance. Anthropologist Stephen Lansing explains how wayang negotiates religious forces within Balinese society:

To create order in the world is the privilege of the gods, but the gods themselves are animated shadows in the wayang, whom the puppeteers call to their places as the puppeteers assume the power of creation. . . . puppeteers are regarded by the Balinese as a kind of priest. However, they are priests whose aim is not to mystify with illusion, but rather to clarify the role of illusion in our perception of reality. As Wija [a well-known dalang] explained: “Wayang means shadow, reflection. Wayang is used to reflect the gods to the people, and the people to themselves.” Wayang reveals the power of language and imagination to go beyond “illumination.” To construct an order in the world which exists both in the mind and, potentially, in the outer world as well. (1983, 82–83)

It is important to remember throughout my account of wayang that it maintains this complex nature: the puppeteer is understood to be speaking for the gods and to the gods; he also functions as a kind of god himself because he has called the world of shadows into being.

Becoming a Dalang

The dalang is the ultimate performer because he4 is the one that manipulates the tradition within a wayang kulit performance and ensures that all the elements of the performance work together. He is the playwright, actor, director, orchestra conductor, musician, singer, producer, and priest all combined into one artist. He needs to be an expert in Balinese philosophy, religion, politics, and myth, as well as a talented storyteller and comedian. The dalang’s skill as a performer, together with his knowledge and perceived wisdom, make him a respected member of Balinese society. It takes a lifetime to master the art of wayang kulit, and a respected dalang is always seeking to improve his knowledge or skill.

In the past, only the son or grandson of a dalang could study wayang kulit. The knowledge about the performance passes down from one generation to the next in many formal and informal ways. For example, Nandhu, my teacher’s son, often sat nearby or on his father’s lap during my lessons. He was just a toddler but had paper puppets and a few small leather ones to play with. In general, children or others are not allowed to touch the “real,” or sacred, wayang; they can only be handled by a dalang or a student, usually an adult, of a dalang. Nandhu learned about the performance through watching his father, through play, and by telling stories with his father. Sometimes an eager youngster might be taken in by a dalang who is not his father, and the student becomes like a son to his teacher and is called anak murid, or child-student.

A major evolution in the process of becoming a dalang has been through the opportunity to study wayang kulit at the Sekolah Menengah Karawitan Indonesia (SMKI), the high school for the performing arts, and at the Institut Seni Indonesia (ISI), the arts university.5 This method of training introduces older would-be dalang to different styles and teaches a couple of the basic stories. A professor in the program, I Nyoman Sedana (1993, 24) notes that for a dalang to really be successful, he must seek additional training outside formal education in high school or university.

My own experience and relationship with my teacher can be understood as a combination of formal education in the university and working with a dalang as a kind of anak murid. My study of wayang kulit began at the University of Hawai‘i and continued at Ohio University, but like the aspiring dalang in Bali, this was not enough. I needed what folklorist Barry McDonald (1997, 64) describes as a “personal relationship” where “emotion, commitment, and deep communication are all crucial entities” in order to understand the tradition of wayang kulit as social action and artistic practice.

I found my “personal relationship” through a chance meeting. My partner, Tina,6 and I had been in Bali only a week, and we arrived in Ubud just in time for a large royal cremation (the largest ever, many papers proclaimed). The sarcophagi were so big that the villagers had not been able to burn them right away, so we returned to the graveyard a couple of days later to see the fires before they completely died out. Intrigued to know more about the cremation, we began chatting with a local Balinese man named Jaga, who was sitting there watching the activity around him. Jaga told us that they had started the fires late at night on the day of the procession and that the cremation towers were still smoldering. He asked what we were doing in Bali, and I explained that I came here to study culture and the arts, kesenian dan budayaan. When Tina mentioned that I hoped to find someone with whom to study wayang kulit, Jaga said he knew a dalang who would be an excellent teacher. Jaga offered to introduce us to him; I decided it was worth investigating and we agreed to meet.

The next morning Jaga met us at our hotel and drove us to Pengosekan, an area in the southern part of Ubud that is known for its strong community of artists. Jaga pulled the car to the side of the road and we walked through the narrow gate that is the typical entrance into a Balinese home. Traditional homes in Bali consist of several small buildings situated around a garden. We passed a statue of Ganesha, the god of wisdom and learning, to be welcomed by a spry-looking man sitting within the central bale, or pavilion. The man, I Wayan Tunjung—or Pak Tunjung, as I would come to call him—welcomed us and asked us to join him sitting on the mat. We drank sweet tea and talked about my desire to study wayang kulit. Pak Tunjung seemed pleased to meet me and eager to take me on as a student; he promised that he would teach me “systematically” and said that I could also learn to carve puppets. We agreed to begin classes the following week and we would meet on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings. When I asked about payment he said that he worked for the love of his art and culture—he did not have a set price. We would figure it out.

I was not the first and certainly will not be the last foreigner to study arts in Bali through a close personal relationship with one or more teachers. Foreigners have a long history of working with Balinese artists—allowing for what Stephen Snow terms “deep learning,” that is, “learning that takes place on all levels: in the mind, heart, and body” (1986, 204). Snow examines the work of Islene Pinder, who studied dance; John Emigh, who studied topeng; and Julie Taymor, who collaborated with several Balinese performers, as examples of three artists who spent extended time in Bali learning and performing to bring those influences into their artistic practice. The benefits, echoing Dwight Conquergood’s (1985, 9–11) notion of “dialogical performance,” allow the artist to successfully negotiate cultural and aesthetic differences to bring a performance genre from one context to another. The idea of “deep learning” could also be applied to Ron Jenkins, Colin McPhee, Carmencita Palermo, Margaret Coldiron, and others who have dedicated a portion of their life and work immersed in Balinese performance. Larry Reed studied Balinese wayang kulit, first with I Nyoman Sumandhi in California and then in Bali with Sumandhi’s father, Pak Rajeg, in Tunjuk. Reed built on that experience to create innovative productions mixing shadow puppets and live actors with his theater company, ShadowLight. Reed’s work attempts not only to transmit Balinese theater forms to an international audience but also to “make it his own” (Diamond 2001, 260). Several scholars who study, perform, and write about other types of puppetry in Indonesia deserve mention. Matthew Isaac Cohen performs Javanese wayang kulit and Kathy Foley performs Sundanese wayang golek; both are masters of the form who draw from their performance experience to enhance their scholarship. The study of wayang “has been possible for foreigners, even actively encouraged, since the 1960’s” (Cohen 2014, 190). Many Balinese also have come to the United States and other countries abroad to work, teach, and learn. Pak Tunjung’s own teacher, I Wayan Wija, has toured the world and embarked on several collaborations with international artists.7 My own experience must be understood as part of a larger international exchange and flux of ideas regarding Balinese performance and wayang around the world.8

For the rest of the summer and then the following year, those Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays became the foundation of my slow initiation into wayang kulit. I have returned to Bali many times to continue learning and to add to my repertoire of stories and knowledge. Often during our lessons or at performances, Pak Tunjung would implore me to remember to honor the tradition of wayang kulit—to perform it “the Balinese” way. He would come up with ideas for my performances; for example, he proposed that instead of the traditional oil lamp, I should get a hat and put different colored lights on it, because I could then light my screen with blue, red, white, or yellow light depending on the mood of the scene. I also went with Pak Tunjung to watch him perform at a variety of ceremonies and events, where many of the Balinese I met would comment that they liked his performances because he was a very “traditional” performer. Sometimes I would watch Pak Tunjung perform wayang tantri, a new form of wayang made famous by one of Pak Tunjung’s teachers, the aforementioned Pak Wija from Sukuwati, which features dynamic animal puppets that were designed specifically for this performance.9 Pak Tunjung often told me stories from the Mahabharata10 and reminded me that it was important for a dalang to know these tales and be able to tell them well. He also described new performances he was creating using other stories or myths from the history of Bali. These discussions and examples demonstrated how “tradition” functions as an affect, or a “process of continual creation of meaning” (Guattari 1996, 159), rather than a stable category. The tradition of wayang changes over time and varies within the present.

As I continued learning wayang kulit, I kept wondering about what it meant to study a “traditional” performance genre. How is tradition constituted through the actions of different individuals? What did it mean for me, an American and a woman, to study this tradition? How might I fit within and outside Balinese social structures? Over time I became a dalang and Pak Tunjung became a kind of older brother to me; through examining this process I better understand how wayang kulit is connected to society and my own place within the tradition.

Tradition, Practice, and Society

I understand wayang as a practice of training and performance that connects to larger Balinese social spheres. The word practice suggests several different meanings, and I purposefully use the term in this multidimensional way. One meaning refers to the practice that it takes to learn a skill, such as learning to play tennis or speak a foreign language. In theater, the definition of “rehearsal” is to practice in order to learn a play. Sociologists have extended the meaning of practice to include the activities we do in everyday life, or our “ways of operating,” which “constitute the innumerable practices by means of which users reappropriate the space organized by technics of sociocultural production” (Certeau 1984, xiv). Practice, therefore, implies repetition connected to and affected by social hegemonies that are enacted through the body. Diana Taylor names this connection between learned bodily knowledge and society the “repertoire,” which unlike written or documented knowledge, “enacts embodied memory: performance gestures, orality, movement, dance, singing—in short, all those acts usually thought of as ephemeral, nonreproducible knowledge.” The key is in the doing, because “the repertoire requires presence: people participate in the production and reproduction of knowledge by ‘being there,’ being part of the transmission” (2003, 20). McDonald focuses the study of tradition on transmission by proposing that “tradition” is “the human potential that involves personal relationship, shared practices, and a commitment to the continuity of both the practices and the particular emotional/spiritual relationship that nourishes them” (1997, 60). Practice therefore provides a means for thinking through how performance traditions are connected to social spheres. Tradition, such as wayang kulit, operates within the body and is passed along from one body to another—reverberating within society.

I want to focus on the moment of transmission as key for unpacking how tradition functions as practice and connects to the greater structures of power within a society. The theories of Pierre Bourdieu, as he is concerned with “the mode of generation of practices,” highlights the relationship between what people do and systems of hierarchy within their society. Bourdieu describes society’s overlying system as habitus:

The structures constitutive of a particular type of environment (e.g. the material conditions of existence characteristic of a class condition) produce habitus, systems of durable, transposable dispositions, structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures, that is, as principles of the generation and structuring of practices and representations which can be objectively “regulated” and “regular” without in any way being the product of obedience to rules, objectively adapted to their goals without presupposing a conscious aiming at ends or an express mastery of the operations necessary to attain them and, being all this, collectively orchestrated without being the product of the orchestrating action of a conductor. (1977, 72)

Habitus, for Bourdieu, is created through primarily unconscious action, or action that because of the “natural” way it is experienced seems to be unconscious. I propose that if habitus is executed through repeated behaviors, therefore “tradition” is a way of identifying one of these kinds of behaviors. Because tradition singles out behaviors or items as having particular meaning in society, tradition is therefore related to the structures of society in an efficacious way. The source of the tradition need not be traceable, and the history of wayang kulit is likewise difficult to recount, so therefore wayang kulit must be studied in the moment of generation as it is passed from teacher to student. So, just as the structures of habitus “are determined by the past conditions which have proceeded the principle of their production” (ibid.), the tradition of wayang kulit is also produced and determined in relationship to the established aesthetics and content of the performance.

Learning a theatrical system physically and mentally, or spiritually, changes the student. Richard Schechner describes how the study of noh, kathakali, or ballet involves “learning new ways of speaking, gesturing, moving. Maybe even new ways of thinking and feeling”; the form changes the body through diligent training and practice, thus “deep, permanent psychophysical changes are wrought.” The performer becomes a shite, the character of Rama, or a dancer and this process changes the performers way of being and relating to the world around him or her—“they are marked people” (1993, 257). Schechner notes that the student brings a blank slate, a tabula rasa, to the training because many of these initiates start learning their craft at a very young age. I, however, began studying wayang kulit as an adult and my exposure to the art form was limited before I arrived in Bali.11 Even so, the bodily experience of learning the form changed me. I was left to wonder, as an outsider, how do I participate in and contribute to Balinese arts and “tradition”? What implications does my participation have for forming a definition of “tradition” in Bali?

Kathy Foley, writing from her own experience learning wayang golek, or rod puppetry, in West Java provides an explanation for the kind of “Balinese” character I could occupy. She writes that learning to perform with the puppets and masks allows performers to “multiply their bodies” through the performance, and that “through the one body we inhabit in this life we can, with the help of these puppets or masks and the ideas they encode, embody the whole cosmos” (1990, 61). The body changes because learning to use puppets begins “by moving away from oneself,” unlike many systems of actor training that begin from the actor’s own personality and life history (65). One of the women dalang I interviewed explained the different skills necessary to perform wayang kulit: “If you are going to perform wayang it is important to practice it all. You need to practice the voice, dancing the puppets, and the foot also. You must become one [menyatu] with the puppets. It is very important. It is important to be able sing and do the voices” (Trijata 2009). Whether in Java or Bali, the performer in puppet theater must learn to physicalize, vocalize, and think a variety of characters that are connected to society through the myths those characters embody and the culture that informs them. Performance provides insight into tradition, as Henry Glassie states: “the performer is positioned at a complete nexus of responsibility” and as such must account for his teachers, the audience, and himself (1995, 402). I inserted myself into the structures of Balinese society by working within the system of the performance tradition. Foley writes, “I feel that my body is still open to the meanings of the practice in itself. Indeed, practice is the only way to get beyond the simple introductions that are found in books and the fragmented, albeit tantalizing information about meanings that come from performers” (1990, 77).12

That I had changed as a result of my experience was noticed by others as well; as this story illustrates: “Om swastiastu!” I called out to my friend Eka as he walked down the path to where I was living in Bali. We met at Ohio University when he was a student there and I was taking my graduate coursework. Now, after living for a few years in Washington, DC, Eka was back in Bali, and after seven months of fieldwork, I was happy to see a familiar face. “Om swastiastu,” he responded with surprise in his voice. “Om swastiastu” is a Balinese rather than Indonesian greeting, typically not known by foreigners. “You speak Balinese?” Eka asked me. “Abidik sajaan,” I answered in Balinese, meaning “only a little.” Eka laughed as he came up the stairs to my balcony. We sat at a little table and sipped hot tea while Eka admired the view of the garden and rice fields that I had from my room. We talked about my research in Bali and I told him I had studied dance and performed at a couple of temple ceremonies. He was especially curious about my experience with wayang. He peppered me with questions: “Do you perform in Kawi? What story are you doing? Are you using an oil lamp? What kind of music? Do you have your own puppets? How often do you go to the temple? You mean you are learning to make the puppets, too?” Eka was truly surprised with all I had been doing. Finally, before he left, he exclaimed with a smile, “My goodness! You are more Balinese than me!”

On the one hand, I knew Eka’s comment was purely out of friendly admiration for all I had been learning and doing over the past year, as there are a lot of foreigners in Bali but very few of them learn Balinese language or spend time doing “Balinese” things. Eka’s words also reflected an awareness that many more Balinese, like himself, are spending less time doing traditional performance and art; the artists I spent my time with do not represent “typical” Balinese. Many people in Bali work in hotels, shops, or for the government and do not make their living as dancers, puppeteers, or musicians. Young people prefer television to topeng and like pop music better than gamelan. Eka’s exclamation, which I received occasionally in some form or another from other Balinese people, reflects a perception, however, that language, culture, and the arts, especially wayang kulit, play a role in the formation of a “Balinese” identity.

Teachers in Bali transmit knowledge and skill of performance to their students through the body. Students stand alongside or behind their teachers to copy movements—teachers will often physically adjust or move their students into the correct pose. The process is not always easy. Emigh describes the difficult nature of his own training in topeng: “daily [my teacher, I Nyoman Kakul] wrench[ed] my resistant body into something approximating the proper shapes for Balinese dance” (1979, 12). I often observed dance teachers with their Balinese students use their hands to adjust a dancer’s hip, head, hand, or leg. If I made a mistake in executing a motion with the puppet, my teacher, Pak Tunjung, would take my hand so he could guide my body and make my movements more precise. Likewise, Pak Tunjung would sometimes sit with his son, Nandhu, on his lap and guide his hand holding the puppet across the screen (fig. 2.2). This is a typical method of teaching in Bali, regardless of age and gender of the students. Jonathan McIntosh describes how a Balinese dancer first learns visually by copying, but then the movements are refined through direct transfer, “the teacher will frequently take hold of a student by wrapping his or her arms around those of the student. . . . Through this process the teacher’s style of dancing and interpretation is kinaesthetically transferred to the student” (2006, 7). One body has power over the other to transfer knowledge of tradition.

Pak Tunjung’s willingness to teach me, body to body, greatly enhanced my ability to learn and to understand the nuanced movement of the puppets. The first time he took my hand, however, he hesitated, and asked, “I will show you, OK?” Age, gender, and ethnicity might have been a factor in his initial hesitation,13 but the question could also be understood as an invitation to fully inhabit the bodily knowledge of the tradition. The student grants the teacher power over his or her body.

Figure 2.2. Pak Tunjung teaches his son, Nandhu, how to perform wayang kulit—the tradition is passed through the body. Photo by author.

Because I learned wayang kulit in my body, the body offers an ideal site for studying the relationship between the past and present as expressed and experienced through tradition. Maurice Merleau-Ponty observes, “The present still holds on to the immediate past without positioning it as an object, and since the immediate past similarly holds its immediate predecessor, past time is wholly collected up and grasped in the present” (1962, 80). People constantly put themselves in relation to objects and time, just as these things are positioned relative to them—the body remains the primary point of reference. Tradition, like habitus, relates to the past, but also like habitus this does not mean tradition reproduces exactly from generation to generation. People improvise interactions within their social situations according to a set of rules and expectations,14 much like a dalang improvises each individual performance according to set rules and expectations. Bourdieu (1977, 73, 76–77) argues that practice within the habitus is neither mechanic or predetermined, nor is it completely a matter of free will, rather that actions or strategies of any individual or group are always conceived and executed within the structures that surround them, and that actions are thus limited by the available possibilities. Bourdieu’s explanation of this situation could certainly apply to how tradition functions as well:

This is why generation conflicts oppose not age-classes separated by natural properties, but habitus which have been produced by different modes of generation, that is, by conditions of existence which, in imposing different definitions of the impossible, the possible, and the probable, cause one group to experience as natural or reasonable practices or aspirations which another group finds unthinkable or scandalous, and vice versa. (78)

My own study of wayang kulit provides an excellent point of departure for pinpointing the structures of the performance and its relationship for society because of the level of learning that I needed to undertake as a foreign woman. An examination of the practice of wayang kulit and later of women dalang allows me to identify the conditions and properties that apply to tradition and to Balinese society on a larger scale. Practice gives me a vocabulary for explaining how tradition has expanded or changed to allow this “unthinkable practice,” of women dalang, to emerge as well as supposing how women dalang might fit into the larger structures of Balinese society and whether this expansion has caused any notable change in the gender hierarchy.

Structures

The structure of a typical wayang kulit performance can often be broken into three parts, or three acts.15 The opening scenes include an invocation to the gods, inviting them to watch and participate in the performance. Next, the main characters enter to introduce the story, which the clowns, or penasar, Twalen and Merdah will translate and comment upon. There might be an additional traveling scene (angkat-angkatan) or love scene (rebong) before the next major act division, which will introduce the antagonist characters. The penasar Delem and his thin brother, Sangut, dominate this scene with their often raucous jokes and antics. The third act provides an arena for the two sides to meet and do battle; it is the climax of the performance. The performance ends with the penasar expressing their gratitude for the patience of the audience and offering the moral or lesson of the story. The dalang then closes the performance with a final ritual dedication, and sometimes he conducts the ceremony to make holy water.16

Arjuna Tapa (Arjuna’s meditation) is a popular story for young dalang to use to learn the practice of wayang kulit, and it is the first story that I learned to perform. In this story Arjuna sets out for the top of the mountain Indra Kila Giri because he is troubled by the war between his brothers, the Pandawas, and their cousins, the Korawas.17 Arjuna worries many people will die because of this war between his family members. At the top of the mountain Arjuna seeks wisdom through offerings to the gods and meditation, so that he might imagine a solution to this problem. Arjuna’s journey up the mountain is not easy; he faces many dangers because he is traveling where few others have gone before. Additionally, his desire for wisdom has made the ogre king, Niwatakwaca, angry. Arjuna does not find peace, and must battle for his life on the mountain, yet eventually the god Indra helps Arjuna by giving him a powerful weapon to destroy his enemies. At the end of the story, Arjuna is whisked away to the heavens, where he will find wisdom and more adventures.

I will use the three-part structure of wayang kulit as a description of my learning experience and as an analytic tool. The first section will focus on the basic aesthetics that are expressed and maintained in a wayang kulit performance. The second section will explore the character of the clowns and how comedy functions as a vehicle for “freedom” and social commentary, even within the set aesthetics and structure. Finally, I will describe the reception of my work, which sometimes caused conflict, in order to connect the practice of learning wayang kulit to practices within Balinese society and ritual. A wayang kulit performance contains action, narration, and commentary; likewise each section contains all these elements.

Part One—Aesthetics

A wayang kulit performance always begins with the kayonan, a large leaf-shaped puppet with intricate carving, in the middle of the screen (fig. 2.3). This puppet, often called “the tree of life” in English, is a symbol of “creative and imaginative forces” (Zurbuchen 1987, 32); it marks the beginning and ending of the performance, it indicates shifts between the three main parts, and it can be used as a transformative prop such as wind, fire, or a chariot. Mary Sabina Zurbuchen explains that the imagery and use of the kayonan in performance “links the dalang to other Balinese ritual specialists who also have access to the ‘unmanifest’ world” (134). The kayonan presents the narration of the play, blurring the distinction between the dalang’s voice and mythic voices of the ancestors represented within the ornate puppet.

At my first lesson, even without a screen, Pak Tunjung taught me how to hold the kayonan between my thumb and fingers so that I could control the movement with my entire hand. Next I learned the first of two kayonan “dances” that begin the performance. I began by holding the kayonan close to my face, and in those moments my breath slowed. As I listened to the music being played by the gender wayang (Gending Pamungkah), my awareness of my surroundings dissipated—I created a connection with the puppet and was thus prepared to perform. Using the cepala, a small wooden hammer held in the hand or toes, which I clutched in my left hand, I knocked slowly on the puppet box and then knocked faster and faster. Pak Tunjung taught me that the knocking begins in time with the music and then as it gathers energy it surpasses the music’s tempo, until it suddenly stops with one forceful final tak. I remembered this lesson as I took a breath and began the knocking sequence, which indicated to the musicians to make the shift in music that would break the kayonan from its position of peaceful contemplation in front of my face and begin an agitated dance against the center of the screen. The gender wayang played two sequences of three beats as I touched the kayonan to the screen, the top of the puppet peeked up from the banana log, and then music and puppet united as I dragged the puppet over to the lower right side of the screen for two small, counterclockwise circles. At the top point of each circle, I paused to take a quick breath with the music before the next circle. Next, the puppet slid over to the left and repeated the same circling motion, but clockwise. After I performed this movement again, once on the right and once on the left, I lifted the kayonan away from the screen. To the audience, the movement looks as though a great gust of wind came up under the kayonan and knocked it from its place. I then swept the kayonan against the screen in large figure eights. I learned to do these figure eights even before I began practicing with the screen, because Pak Tunjung wanted to teach my body and make my muscles strong in order to gracefully execute the correct movements.

Figure 2.3. The kayonan puppet begins the performance at the center of the screen. Photo by Tina (Cox) Goodlander.

This opening dance of the kayonan demonstrates aesthetic rules that connect the performance to Balinese society and religion. Anthropologists Bruce Kapferer and Angela Hobart suggest that the consideration of aesthetics provides a means to unite art with life:

The aesthetic and its compositional forms are what human beings are already centered within as human beings. This is to say that human beings are beings whose lived realities are already their symbolic constructions or creations within, and through which, they are oriented to their realities and come to act within them. To concentrate on the aesthetic is to focus on the dynamic forces and other processes engaged in human cultural and historical existence as quintessentially symbolic processes of continual composition and recomposition. If the aesthetic is to be equated with art, then art is life, an attention to its aesthetic processes being a concern with its compositional forms and forces in which life is shaped and comes to discover its direction and meaning. (2005, 5)

The kayonan dance thus acts as an aesthetic symbol and the practice of its use in performance demonstrates how wayang kulit makes meaning within Balinese culture.18

Missing from Kapferer and Hobart’s use of aesthetics as an interpretive tool is the judgment that a theory of aesthetics implies; there are “good”—or within the culture, desirable—aesthetics or “bad,” or undesirable, aesthetics. Bourdieu articulates how aesthetic judgment is connected to social hierarchy through his theory of taste. Bourdieu refers specifically to distinctions and comprehension of Western art, and thus not all his work is relevant; the idea, however, that understanding the art form and finding it pleasing and therefore worthwhile according to a set of established and learned rules reveals much about how wayang kulit is judged as pleasing or not pleasing and thus given a kind of tangible value within the society. If the viewer does not possess the “cultural competence” in order to understand the performance, he or she “feels lost in a chaos of sounds and rhythms, colours and lines, without rhyme or reason” (1984, 2). While in Bali, many of the foreigners I encountered expressed similar frustration with Balinese performance because they never acquired knowledge of the cultural codes and language being used in the performance. The value given the aesthetic codes also mitigates how women might be perceived and accepted as dalang.

Taksu, the primary Balinese aesthetic, describes an elusive quality that a performer or performance has in order to be judged as good, meaning that the performer pleases his or her audience and the performance is therefore deemed successful. Taksu connotes a certain spiritual connection or even age because it is something accumulated over time, and as a performer practices and gains performance experience, the performer’s taksu develops. Having taksu is different from being a skilled performer—even a master might have an off night and a beginner might give a performance with strong taksu. Hobart (2003, 115) dubs taksu “the god of inspiration,” which provides the dalang with the power to execute the performance. Edward Herbst calls taksu the means by which the dalang is connected to the invisible world of the spirits: “Once the shadow puppet is in the dalang’s grip, his hands and arms serve as a connector, a lightning rod, through which the puppet’s character, voice, and spiritual life-force, taksu, enter the dalang” (1997, 61). In order for this connection to manifest and create taksu, there must be, however, a logical connection between dalang and puppet. This connection is described as masolah, or “characterization”—“masolah in its fullest meaning implies the inherent taksu ‘spiritual energy’ that integrates the state of a performer with the physical form of his own body, and/or that of a mask or puppet” (57). Pak Tunjung explained to me, “within a wayang kulit performance masolah is extremely important. It is the medium of action—the dalang must dance together with the character of the puppet. In Balinese wayang kulit, masolah provides the means for the message or meaning of the performance.”

The realization of masolah, and the creation of taksu, depends on a logical connection between the puppet and the dalang. No connection, no taksu. Herbst describes several dalang finding difficulty with the animal characters in wayang tantri—because how can a human dalang become one with an animal character? In wayang “each character really must speak for himself, with no distance between dalang and puppet” (1997, 62). This creates difficulty for a woman dalang to have taksu because there is a greater social, vocal, and physical difference between her and the many male characters in the stories she performs. I had studied various styles of Asian performance while at the University of Hawai‘i and often played male characters. This experience helped me greatly in bridging the gender and cultural divide between myself and the puppets I held in my hand. A male dalang can play female characters and a woman dalang can play male characters. However, it is rare to see women characters in wayang—and perhaps the greater distance between puppet and character, which is an obstacle to taksu, is why.

“Liveness” and “balance” are two additional aesthetics that are important to master for wayang kulit—the connection of masolah does not depend on voice alone. From the Balinese perspective the universe is made up of three key elements—fire, water, and air—which are constantly moving and changing. Some change is visible and some change takes place over such long periods of time that it is not readily apparent. The Balinese consider the presence of this kind of subtle movement—called kehidupan, or liveness—to be highly desirable within the performing arts because a static puppet or dancer appears dead. Kehidupan explains why most Balinese wayang kulit is still performed with an oil lamp even while Java and most of Southeast Asia now prefers the stronger light given by an electric lamp. The flickering flame from the oil lamp creates the appearance of constant movement and “life,” even while the puppets are not moving. Pak Tunjung reminded me about the importance of my wrist; he explained that I needed to keep the kayonan in constant motion. The kayonan puppet is large but is made of thin leather that quivers with a slight wiggle of the wrist. I learned that it is important to coordinate this vibration with all the movements of the kayonan; it must look alive.

The ideal of balance, or the existence of two opposite yet complementary halves composing a whole, is a pervasive and long-standing foundation for Balinese culture and cosmology. Davies (2007, 21) asserts that balance is the primary criterion for judging whether something is beautiful, pleasing, or good—or in Balinese, becik. Balance in Balinese art forms is not just a matter of symmetry; it also depends on how the proportions relate back to both the human body and the cosmological configuration of the island. Balance, rather than finding expression through opposites, also recognizes a middle position between the two extremes, and much of Balinese ritual and performance strives to bring these extremes together in equilibrium. For example, temples are placed and designed in orientation to the ocean, mountains, and cardinal directions, linking sacred elements through position and proportion (James 1973, 145–48).

Balance can be expressed through gender within Balinese performance. Many elements of a performance can be coded as masculine or feminine, such as different pairs of instruments or specific types of movements. A performance can also find balance within the gender of the performers or characters. The aesthetic realization of balance within the puppets is best understood within the categories of alus and kasar. Alus roughly translates as refined, and kasar is unrefined (fig. 2.4). Many different features of the puppets communicate the personality of their characters to the audience.19 Characteristics of an alus puppet include a smaller, slim body, a head that is tilted downward, small or narrow eyes, a small mouth, and a small nose. The puppet’s kinesthetic sphere of movement will also be smaller and more delicate. A kasar puppet is often much larger, has big, bulging eyes, a large open mouth with teeth or a tongue showing (or both), is looking straight ahead or upward, and has a wide stance. Kasar puppets move much more vigorously on the screen with large sweeping motions. Vocal qualities also follow the physical characteristics of the puppets. For example a kasar ogre would have a very rough, loud, and deep voice, while an alus god or hero would have a higher pitched, rhythmically slow, smooth, and melodic voice.

Figure 2.4. The characters of Momosimoko (left) and Arjuna (right) demonstrate the difference between kasar and alus. Photo by author; puppets by I Wayan Tunjung.

Many different features of the puppets communicate the personality of their characters to the audience. In his dissertation on Javanese wayang kulit, Jan Mrázek (1998) analyzes the wayang character as if it were a map because important details such as the face are crafted on a larger scale to provide greater detail.20 Similarly, a map of a state often includes a blowup of important cities to show individual streets and landmarks. The dimensions of profile as well as their forward-facing position are mixed to contain as many details of the character as possible. The audience sees both shoulders, a side view of the head, both legs and arms, but the rest of the body is in profile. Within the categories of alus and kasar, the features can be mixed and matched and there are many shades of possibility in between the two poles. One feature cannot be read by itself but only in combination with all other features. The stylistic iconography is born out of practicality—there is a conscious effort to communicate with the audience as completely as possible.

In Bali, however, gender connects to the available range of refinement; for example, an ogre would be kasar and a prince would be alus. Most women characters are limited to alus. In casting, women often play refined male roles in dance dramas and men monopolize the kasar ones. The scale of alus and kasar suggests why I was able to study and perform wayang kulit in Bali with little obstacle. I am female and often strove to act according to the codes of conduct for women in Bali (I dressed conservatively, did not drink alcohol in public, did not smoke, and so on). As a foreigner, however, I also had greater opportunity to occupy a kasar place and to effectively perform those characters. For example, most Balinese undergo teeth filing “to distance themselves further from the fanged animal world” (Emigh and Hunt 1992, 204). I had not undergone such a ceremony. A Balinese woman as dalang risked disharmony with the characters of the puppets according to the precepts of alus and kasar, a danger that I, as a foreigner, did not share.

Within Balinese philosophy there is the idea of “Tat twan asi,” or “Thou art that,” meaning “that every individual potentially contains within himself or herself the entire universe” (Emigh and Hunt 1992, 203). In wayang, the kayonan dance demonstrates balance between the different dimensions of the universe as it moves around the screen. The body of the dalang begins the performance by connecting to the physical and invisible worlds; enacting balance through motion. Movements on the left are matched with movements on the right, and there is also balance in how the kayonan moves between the top and the bottom of the screen. Pak Tunjung often adjusted my hand in order to facilitate this balance; I did not automatically create the same movement on the right and left but had to practice it again and again. When I first learned this section, often on the right side, the tip of the kayonan tended to slip too far down while on the left it stood up too straight. The next important motion of the kayonan dance I learned was to spin the puppet in the palm of my hand. Pak Tunjung demonstrated how I needed to set the point of the stick in the center of my palm while wrapping my fingers around the upper part of the stick. I needed to balance the kayonan in my right hand while using my fingers to make it twirl off toward the sides of the stage. During this twirling, I again used the cepala in my left hand to knock against the puppet box. All these elements needed to work together.

Most of my lessons were during the day, without an oil lamp. Finally, when we rehearsed with the lamp, I had to again learn how to adjust my body to complete the motions with something hanging directly in front of my face (fig. 2.5). I found that I needed to watch both the puppet in motion and the shadow being created on the screen. Twirling the kayonan near the lamp forced me to be aware of my body in relation to the puppet in a new way. The puppet’s motions were no longer just about the motions; I now needed to watch the result of those motions, and the shadow was the visible result of the invisible intention that resided in my body.

Figure 2.5. The oil lamp hangs in front of the dalang’s face. Photo by author.

As the dance of the kayonan is completed, the dalang and his assistants take out the rest of the puppets from the box and put them into their places around the stage. There is another section of the kayonan dancing before the puppet characters enter the scene and begin the story. The entrance of the puppets is called Alas Arum and is accompanied by music and a song. The length of the song can be adjusted depending on the number of characters entering. The version that Pak Tunjung taught me for Arjuna Tapa is:

Alas Arum

rahina tatas kemantian humuni

Every morning the gamelan music begins to play.

mredanga kala sangka gurnitan tara

The voices of the instruments are beautiful to hear.

gumuruh ikang gubar bala samuha

The sound of the crashing cymbals brings everyone together.

(Arjuna enters.)

Mangkata pada nguwuh seruh rumuhun

And the one with the thunderous voice progresses to the front of the line.

(Arjuna ties his sash and fixes his crown.)

Para ratu sampun ahyas asalin

The kings change into their grand clothes.

(Twalen enters.)

Lumanpaha pada hawan rata parimita

He that drives the chariot is without compare.

(Merdah enters.)

Arjuna is the first character to enter from the dalang’s right. Pak Tunjung demonstrated how I must combine singing, the motion of the puppet, and the percussion of the cepala in this short sequence. He taught me this section by taking my hand and allowing me to feel the movements in my body; he wanted me to sense the tension of the puppet on the screen. When Arjuna stopped moving, Pak Tunjung pressed down on my hand, pushing the Arjuna puppet into the screen, and then quickly he relaxed the pressure. Next he tilted my hand in order to make Arjuna look down. “Arjuna is looking at the place around him,” explained Pak Tunjung, “he is acknowledging the world that he has entered into.” Arjuna then slowly moved counterclockwise, to the right side of the screen. The characters who are the heroes of the story often enter and are placed on the side of the screen to the dalang’s right, while the left side is preferred for the villains of the story. When Arjuna reached the correct place, I stuck the sharp stick of the puppet into the banana log.