Читать книгу The Bernward Gospels - Jennifer P. Kingsley - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

MEMORY

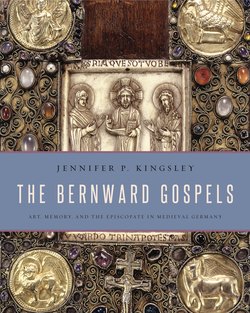

The presentation of the Bernward Gospels as a founder’s gift to Saint Michael’s Abbey in Hildesheim underlies the commemorative nature of its program and is the apparent subject of the painted bifolium inserted between the incipit and text of Matthew’s gospel (fols. 16v–17r; plates 2–3 and fig. 4).1 The miniature depicts Bishop Bernward on the left folio. He raises a closed book in both hands in a gesture of donation, but he does so before an altar set with a portable altar, chalice, and paten, instruments for the celebration of the Eucharist—making his gesture an act of liturgical performance. Bernward faces Mary and Christ; they appear on the right, enthroned between the archangels Michael and Gabriel, whose open arms frame the Virgin and her child like a mandorla. These four are the patron saints of the abbey church’s crypt, which Bernward consecrated in September 1015 (and where he would be buried in 1022).

The tituli in the painting’s frames verbalize Bernward’s act primarily as one of donation, identifying Mary and Christ as the recipients of Bernward’s codex. Composed, for the most part, in leonine hexameter, the text reads, on the left folio,

This small book of the Gospels, with a devoted mind

the admirer of Virginity hands over to you, Holy Mary,

Bishop Bernward, only scarcely worthy of this name,

and of the adornment of such great episcopal vestment.

A further dedicatory line appears in silver letters on the right folio, in the arch above the saints’ heads. It completes Bernward’s offertory statement.

He presents [it], Christ, to you and to your holy mother.2

The miniature’s composition adheres in many respects to the conventional characteristics of early medieval donation pictures. Mary and Christ respond to Bernward’s gift with a gesture of blessing that places Bernward in the guise of a Magus at the Adoration, the prototypical medieval donor.3 Unusually, however, Bernward’s act of gift-giving is directed across an altar set with liturgical objects for the celebration of the Eucharist and he wears vestments for the Mass: the amice, alb, dalmatic, and stole.4 There exists no exact parallel for this in medieval donor imagery, although a number of Ottonian donation scenes use the format of a bifolium, and in the Middle Ages offerings for the saints were generally presented to their altars.5 A painting in an Ottonian manuscript produced in Reichenau that is now in the Walters Art Museum alludes to such a practice (Baltimore, Walters Art Museum, W7, fol. 9v; fig. 5). The picture portrays a church setting in which an abbot hands a codex to Saint Peter. The saint, in turn, opens a door (note the small hinges), revealing an altar. There, the book already appears with a new cover; from above, the hand of God gestures a blessing. Both details suggest that the abbot’s gift has been transformed at the altar, giving proof of the donor’s merit and signaling that his offering has been accepted by God.6

Yet comparing the Reichenau dedication picture to the Bernward Gospels underscores the important differences between the two rather than their similarities. In the former, the donor stands before the recipient to offer the codex directly to the saint, as is usual in donation scenes.7 The altar appears on the other side of the saint and of a door; each adds to the distance between the donor and the altar. Furthermore, while the altar is covered in textiles, nothing appears on it other than the book. In the Bernward Gospels, however, the altar has been made ready for the Mass. It is covered with textiles, and in front of it are five candlesticks, while above are the chalice and paten, which stand on a portable altar. In these details, the painting draws on the iconography of the Mass. On the late tenth-century ivory panel now in the Liebieghaus Museum in Frankfurt-am-Main, the celebrant similarly stands inside the church, before an altar covered with textiles and set with a chalice, paten, two candlesticks, and two books, one open and one closed (fig. 6). He is garbed in sacerdotal vestments and holds both hands to his chest with palms facing outward. Five clerics stand in a semicircle behind him; they hold closed books. On the other side of the altar, five monks raise their arms in prayer and appear to be singing the Sanctus. The ivory offers an accurate evocation of the Mass. In comparison, the miniature in the Bernward Gospels is less specific; the scene does not correspond to any particular moment in the Mass.8 Nonetheless, by presenting Bernward in a pose of offering and before an altar prepared for the Eucharist, the painting suggests that both donor imagery and liturgical ideas inform the picture’s design.9

The composition relates Bernward’s space to the setting of the saints in a way that draws further on liturgical ideas associated with gift-giving. The architecture on the left folio mimics that of the right. Both buildings consist of three arched bays. On the left, the depiction of Bernward’s church combines a view of the interior with one of the exterior, resulting in two levels. On the right is a more continuous space unified by the deep purple curtain in the background. Its patterning relates it both to the roof of Bernward’s edifice and to the altar covering there. An orange border patterned with white dots lines the edges of the curtain, delimiting the Virgin’s space. It echoes the pattern of the cornice line of Bernward’s church. On both pages appear gold and silver spiraling columns. One set frames the Virgin, while the other, on the left folio, appears at the clerestory level of the building. Together the curtain, orange bands, and columns relate the Virgin’s setting specifically to two areas of Bernward’s church: its exterior level and the ritual space of the altar. Such framing devices locate the Virgin outside the boundaries of Bernward’s church but link her to the altar, helping present the Virgin’s setting as a heavenly reformulation of the bishop’s earthly edifice.10

Between the two depicted spaces, earthly and heavenly, stands the altar, which serves pictorially as the connection between Bernward and Mary. Taking up more than a quarter of the left folio and placed on an elevated platform accessed by two steps, the altar dominates the painting. It also crosses over the external edges of the building. By projecting beyond the structure, the altar stands ambiguously both inside and outside the church, moving toward the heavenly setting on the opposite page. On that folio the frame’s edge is an open door, one of the pair labeled “door of paradise.”11 Whereas the door on the right is marked closed (clausa), the one facing the page’s inner margin, and thus Bernward’s altar, is open (patefacta), giving access to the saints.

The painting’s careful rendering of the relationship between Bernward’s earthly church and the Virgin’s heavenly edifice resonates with Eucharistic theology. Mass commentaries of the early Middle Ages point to the concordance between the earthly and heavenly altars, the communion of the faithful and the heavenly communion of the angels. After all, no less an authority than Gregory the Great had proclaimed that at the consecration of the host the angels were present, the earthly was joined to the heavenly, and the visible and invisible became one.12 The idea that the consecration of the Eucharist opened the heavens laid groundwork that would have particular importance for eleventh-century ideas about gift-giving, a point to which I shall return later in this chapter.

A second set of inscriptions in the painting offers a series of metaphors for the Virgin that emphasize her role in Christ’s Incarnation, a theme not only appropriate for a portrait of the Virgin but one that also relates to the Mass, wherein the transformation of the bread and wine into Christ’s sacramental body is linked to Christ’s Incarnation.13 Painted above the dedicatory words on the upper corners of the picture frame appears the phrase “By this speech she conceived God and gave birth to him.”14 An inscription in the lower frame completes the verse: “Virgin Mother of God trustful of the words of Gabriel.”15 Additional tituli run over the three arches of the colonnaded arcade painted behind the Virgin; they record epithets for Mary cast in the formula of Gabriel’s greeting at the Annunciation.

Hail Star of the Sea, shining through the grace of the Son

Hail Temple unlocked by the Holy Spirit

Hail Door of God closed after the birth through the ages16

Two final inscriptions appear on the doors at each side of the frame. They repeat the metaphor that describes Mary as a door: “The door of Paradise closed through the first Eve, now is through Holy Mary thrown open to all.”

The designations “star of the sea,” “temple,” and “door” refer to titles for Mary common in the West since at least the Carolingian period.17 However, a tenth-century poem by Hrotsvit, a nun at the convent of Gandersheim in the Hildesheim diocese, uses these metaphors in a way that clarifies their specific meaning for the Bernward Gospels.18 In her verse narrative of the Virgin’s life, Hrotsvit explained that Mary received her name because she was a bright star shining from Christ’s diadem.19 The painting provides a visual echo of this statement. The angels Gabriel and Michael seem to be crowning the Virgin; the way they hold her diadem results in their index fingers’ pointing to its central decorative element, the shining “star” of Hrotsvit’s text, although Mary rather than Christ wears the crown here.20

Labeling Mary “the temple” echoes an epithet Hrotsvit used to describe the Virgin in a later stanza of her poem, where she explains that the title stemmed from the fact that Mary had been weaving the purple curtain of the Jewish temple at the moment of the Annunciation.21 The miniature presents a similar relationship between Mary and the temple pictorially by locating the Virgin before an architectural structure that features a purple curtain as well as twisting columns, a further symbolic reference to Solomon’s temple.22

The third metaphor, that Mary operated as an open door, helps present the Virgin in a typological relationship with Eve. Together with the inscription in the frame of the right half of the painting, this epithet conveys how, by accepting the role Gabriel announced she would play in Christ’s Incarnation, Mary reversed Eve’s actions, which had caused mankind to be expelled from Paradise. Thus Mary helped open the path to heaven that had been lost by man’s original sin. The picture also translates this trope into visual form. Above the two doors labeled portae paradisi that flank the central figures of the painting are two roundel portraits of Mary and Eve. Although not used in Hrotsvit’s poem, the description of this typological relationship between Mary and Eve was common in contemporary sermons for the feast of the Assumption.23

In the Bernward Gospels, these metaphors for Mary are structured as Gabriel’s salutation to the annunciate Virgin and thus emphasize her role as the bodily host for Christ’s Incarnation. Yet the inscriptions do more than simply reiterate conventional titles for Mary. They also draw attention to the realization of these epithets in material form by means of their representation as a series of pictured things: a crown, textile, building, and doors. Together, the ways in which the composition connects the two halves of the opening to each other, the miniature’s combination of donor imagery and Eucharistic content and the right folio’s pictorial rendering of the tituli’s verbal metaphors, establish a complicated mechanism of dynamic play between word and image, picture and ritual, visible and invisible.

By prompting the viewer to engage with this process, the painting cues a series of cognitive responses in which the crown, curtain, and doors are suddenly revealed as both objects and allegories for Mary, while the representation of Mary herself becomes both a portrait of the saint and an image of a cult statue. In the dedicatory opening the Virgin and Christ are characterized by a frontal pose, speaking gesture, and metallic clothing. A very small Christ floats in an upright posture on the edge of Mary’s lap. Both figures have been depicted in a highly symmetrical manner, but certain details add a touch of liveliness. For example, the knees and feet of both figures splay outward rather than mirroring each other exactly. Mary and Christ also both open their right hands, gesturing toward the side. These formal aspects, along with the gold and silver drapery over Mary and Christ’s bodies (including the cowl that descends over Mary’s shoulders), closely reflect the appearance of a contemporary sculpture that is an early example of the so-called Throne of Wisdom type (fig. 7). Still extant in Hildesheim’s cathedral, it is a statue with which the Bernward Gospels artist was likely to be familiar. This sculpture was made under the bishop’s direction in the early eleventh century, and in Bernward’s time it consisted of a wooden core covered in gilded silver, echoed in the painting by Christ’s and Mary’s gold and silver vestments.24 It is probable that the statue, like the Virgin in the miniature, originally wore a crown. According to historical sources in Hildesheim, a “new” crown was made for the statue in 1645, suggesting that it may have already worn one before then, and a crown is already associated in the eleventh century with the oldest extant Marian statue, a tenth-century sculpture from the royal nunnery of Essen.25

The materials in which Mary and Christ are rendered are especially significant to considering whether the dedication painting represents a statue. Compared to other depictions of figures in the manuscript, including what is conceptually the closest parallel, a painting of Christ in Majesty (fol. 174r; plate 14), the complete covering of Mary in gold and silver makes her figure read as a metallic object. In the dedication painting, that combination of materials is reserved for the objects around the altar, set pieces of the architecture, and two of the inscriptions. What these elements have in common is their representation as manufactured things.26 Even the inscriptions, with their carefully delineated silver capitals laid on a gold ground, resemble engraved letters such as those that appear on the back cover of the Bernward Gospels (plate 18).

It is probable that the depiction of Mary does not merely act as a general sign for a cult statue but instead depicts the particular sculpture made under the direction of the manuscript’s patron, Bishop Bernward. Artistic copying in the Middle Ages varied in its levels of specificity and verisimilitude, usually indexing what were considered to be significant parts of the model in order to indicate a relationship between model and copy.27 The picture of a sculpture accompanying its written description in a codex now in Clermont-Ferrand (Clermont-Ferrand, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 145) illustrates this point. Inserted into a book primarily devoted to the works of Gregory of Tours is the description of a Madonna and Child statue commissioned by Bishop Stephen of Clermont-Ferrand in 947. The text includes an account of the statue’s history, including the recitation of a vision that had justified its making. In the margin appears an ink drawing of that very sculpture (fol. 130v; fig. 8). Although its iconography follows the description of the statue to some extent, the sketch portrays the Virgin in profile (as if part of an Adoration picture) and includes a halo, which was certainly not a feature of the Clermont-Ferrand sculpture.28 The drawing in this instance thus reflects only some aspects of the statue’s appearance, and it is primarily the text that confirms the relationship between the drawing and an actual object.

Such an approach to copying is broadly consistent with medieval conventions for representing artworks not only in images but also in texts.29 In the early Middle Ages, descriptions of artworks appear sporadically in narrative sources and frequently in property inventories. An example especially relevant to Hildesheim is an Ottonian account of a series of reliquaries that may have been written either at a monastery in Lamspringe, near Hildesheim, or in Hildesheim’s cathedral (Wolfenbüttel, HAB, 427 Helmstedt, fol. 2r).30 The text provides a useful case study of early medieval descriptive conventions for artworks: “This [relic] is contained in a glass case.... This is contained in a case, the cover of which is carved with the lamb of God.... These are contained in a case that is painted with a green color.... These are contained in an oblong case with red paint without so much viredine.... These are contained in a case that on the cover presents the likeness of the throne of the Lord.”31 This laconic inventory describes the reliquaries only sparsely, yet identifies select distinctive details to help distinguish individual examples within a single corpus. In the first instance, the list mentions the case’s material. In two separate examples, the text cites the color of the object and provides a brief explanation of the picture visible on the casket’s lid.

Such lack of specificity suggests that the writer of the inventory assumed his readers would have independent knowledge of the treasury.32 In this circumstance, the description would serve essentially as a mnemonic cue for something already familiar. Indeed, the text’s careful delineation of distinguishing characteristics within a more generic description relates directly to how medieval audiences learned to remember things.33 Rhetorical and meditative treatises that lay the basis for how medieval authors described mnemonic processes emphasize the forming of mental pictures as an aid to memory.34 In these texts, images are considered effective for remembering if they evoke something known by fixing minimal distinctive details in the mind—such as, in the descriptions discussed above, the material or color of an object, or, in the Bernward Gospels painting, the figures’ pose together with their gold and silver robes. To make the visualization even more memorable, the image could be elaborated by invention.35 That is, medieval systems of memory relied not on mimesis but rather on creative mental indexing. Read against such practices, the painted statue in the Bernward Gospels reproduces the appearance of Bernward’s sculpture with surprising fidelity. In this connection, the high level of verisimilitude in the reproduction of the Marian statue in the Bernward Gospels is significant.36

Why engage the memory of a golden cult object donated by the bishop to the Cathedral of Hildesheim in the representation of Mary and Christ in the Bernward Gospels, a manuscript intended for the monastery of Saint Michael’s? While reproducing a gift in a medieval donor image is to be expected and the sketch of the Clermont-Ferrand statue logically accompanies a text about the object, the painting in the Bernward Gospels follows from neither principle. Moreover, although the merging of the reproduction of an object with the image of the Virgin and Child is consistent with the painting’s tendency to play with varied and related referents, it comes dangerously close to what medieval theologians defined as idolatry, the conflation of a manufactured object with the saint to which it refers. To parse what was at stake in painting an image of the golden Marian statue in the Bernward Gospels requires an analysis of the characteristics of this object and its eleventh-century context.

The statue is a sculpture that seems always to have been part of the treasury of the cathedral, whose main altar was dedicated to Mary. In 1840 Johann Michael Kratz wrote that the figures were “mit Heiligtümern angefüllt” (filled with holy things), and during a restoration in the 1950s, conservators opened the large cavity closed by a wooden panel in the statue’s back to find small bits of wood there.37 The nineteenth-century description together with the hidden opening and wooden pieces raised the possibility that the statue functioned as a reliquary and was perhaps designed as such.38 Since no contemporary records pertaining to Bernward’s golden statue exist, the object’s exact use in Hildesheim remains difficult to reconstruct. Yet it can partly be extrapolated from liturgical conventions attested to at other Ottonian churches. By the eleventh century, statues of the Virgin and Child actuated the presence of the saints during the rites and processions of high feast days dedicated particularly to Mary, such as the Assumption, and on certain feasts of the Christmas and Easter seasons.39 As an image of the patron saint of the cathedral, the Hildesheim sculpture might also have been processed through Hildesheim to commemorate important anniversaries in diocesan history, such as the cathedral’s dedication. A sixteenth-century source records that just such a reliquary procession was the custom in the later Middle Ages; the extent to which this reflects earlier practices is, however, difficult to ascertain.40

What Bernward may have anticipated the statue would mean to the Benedictine community dedicated to Saint Michael that he founded (and for which he constructed a walled complex just outside the town limits) is even less certain. However, the altar of the monastic church’s crypt was dedicated primarily to Mary, and late medieval sources indicate a stational processional took place on Palm Sunday and included Saint Michael’s.41 Regardless of whether Bernward’s sculpture was ever carried to Saint Michael’s on these occasions, the monks may also have had occasion to see it displayed in the cathedral on high feast days.42

A sense of the significance such statues had for medieval communities can be derived from Bernard of Angers’ tenth-century chronicle of the miracles of Sainte Foy in Conques. It offers a window into contemporary ideas about statues of saints, which were becoming increasingly popular in the tenth and eleventh centuries: “For it is a deeply rooted practice and firmly established custom that, if land given to Saint Foy is unjustly appropriated by an usurper for any reason, the reliquary of the holy Virgin is carried out to that land as a witness in regaining the right to her property.”43 In other passages, Bernard describes such statues holding councils and appearing in visions.44 Bernard’s account reveals the extent to which these objects served to authorize, support, and advocate for communities’ spiritual and legal claims, thus acting not only as liturgical objects but also, potentially, as public carriers of memory.45 The painting of the Virgin and Child thus reproduces a type of object that the patron and recipients of the codex would have understood to bear a high degree of symbolic power in rituals of a liturgical as well as a commemorative nature. It also, significantly, represents a contemporary work of art associated with Bishop Bernward.46

Related observations can be made about other objects depicted in the dedicatory bifolium. As mentioned above, the two rectangles depicted to each side of the saints on the right folio are topped by roundels containing portraits of Mary and Eve; these painted doors present a typological relationship between the two women. The verses together with the portraits echo the iconography of monumental bronze doors commissioned by Bernward for Saint Michael’s Abbey that were completed by 1015, contemporary with the Bernward Gospels.47 These depict, on one panel, narratives from Genesis centered on Eve, and on the other, corresponding moments in the life of Mary and Christ. Both the painting and bronze door present Eve as responsible for closing the doors of Paradise when she gave in to the serpent’s temptation, and they make Mary’s acceptance of God’s message the reason for the gates’ reopening. Both also interpret Mary as the new Eve, arguing that salvation is made possible by Christ’s and Mary’s reversal of Adam’s and Eve’s actions.48 The doors are now displayed in the cathedral but were probably designed for Saint Michael’s.49

Although the reconstitution of their original location remains somewhat disputed, as doors, the bronze panels operated as thresholds between spaces and in that way served as liminal zones in a manner similar to Bernward’s golden statue, which mediated the presence of the saints for the faithful. The miniature argues through pictorial means that the painted doors function as much as portals as their bronze referent. As already described, an inscription proclaims that the door on the Virgin’s left, the one bearing Eve’s portrait, is clausa (closed), and it is pictorially highlighted as such by the prominence of the hinges which jut into the adjacent column. In contrast, the door on Bernward’s side is marked “cunctis patefacta” (thrown open to all), and its location at the edge of the picture frame presents it as a passageway to the saints.

Like the Marian statue, the bronze doors may have played a public role in constructing the memory of a specific moment or event at Hildesheim. In a study of the doors, Adam Cohen and Anne Derbes suggest that the panels depict Eve as a sexually provocative woman as part of a project to identify a local nun (and sister to the emperor), Sophia of Gandersheim, as malevolent and dissolute. In historical texts produced in Hildesheim, Sophia was held responsible for prompting the efforts of the archbishop of Mainz to lay claim to the wealthy nunnery of Gandersheim that the bishops of Hildesheim considered to be under their aegis.50 By offering a polemical argument against the dangers posed by seductive and insolent women, the doors may have served to assert Bernward’s legal and spiritual claim to this nunnery. Completed shortly after the initial settlement of the dispute in Bernward’s favor, the doors thus potentially directed the diocese’s memory of a specific conflict in a public statement of Bernward’s authority. The memorial association between the doors and the patron is especially significant; within the inscription on the panels appears the phrase B[ernwardus] ep[iscopus] dive mem[oriae] (Bishop Bernward, blessed of memory). Reproduced in the dedicatory painting, the depiction of the doors may help reiterate and extend that commemorative message.51

In the painting, a white cross appears within the blue opening of the left door, marking the passage as the way of Christ. It consists of two parts: a crucifix and a long handle that extends to the bottom frame of the picture. The latter detail indicates that the object is a processional cross. The representation here is particularly generic. Nevertheless, processional crosses were important objects for the liturgy and Bernward did commission several in Hildesheim. For example, a gilded silver cross now in the diocese’s museum dates to the eleventh century.52 It bears the inscription “Bishop Bernward made this” (meaning “had this made”) on its verso, together with a list of saints, including Dionysius, whose relics were purportedly presented to the bishop by the king of France in 1007.53 This cross was at Saint Michael’s until the nineteenth century and, like the golden statue and bronze doors, served to commemorate both the bishop and the community, as it bears the patron’s name on its back together with a list of relics to which the monks would add in the later Middle Ages.54

An important ritual object, the cross would not only have been carried in processions but also, detached from its base, would have stood at the altar to represent the presence of Christ during the Eucharistic celebration. Thus like both the statue and doors it played the role of a mediator between man and God, earth and heaven, which the picture in the Bernward Gospels underscores by the cross’s placement in the passageway to Paradise. A parallel in the Bible Bernward gave to Saint Michael’s emphasizes this point. As discussed in the introduction, the Bible’s dedicatory painting is a complex and layered image (DS 61, fol. 1r; fig. 1). A processional cross dominates the picture and its embellishments of gold medallions, incised lines, and punch marks, together with the entwined vines and punch marks between the cross’s arms, are carefully rendered details that mimic contemporary metalwork.55 The low curtain that wraps around the cross’s base can be understood as an altar covering. The painting thus represents, on the one hand, a golden processional cross standing at the altar inside a church.56 On the other hand, the picture draws on Crucifixion iconography, and the golden cross is shown to reach the heavenly opening at the top and right side of the painting, where the blessing Hand of God reaches into the church. Like the painting in the Bernward Gospels, the Bible’s miniature thus conflates the representation of a work of art with the evocation of the Crucifixion, adding an extra charge to the sign’s theological and liturgical importance in denoting the presence of the divine.

In the Bernward Gospels, the prominent purple curtain hanging behind the Virgin adds to the objects on the page that are identifiable as works of art mediating access to the divine. A silk pasted into the back cover of the Bernward Gospels and another found covering relics sealed by Bernward’s predecessor indicate the presence of Byzantine textiles in Hildesheim.57 Although, like the processional cross, its depiction is generic enough that tying it to a specific work at Saint Michael’s is impossible, it is another reference to a valued category of object commonly found in churches of the period. The composer of the dedication inscription on the left folio indeed highlights the importance of liturgical textiles in Hildesheim when he notes Bernward’s ceremonial vestments, whose repeating weave pattern marks them as silk: ornatus tanti vestitu pontificali.

While there is no evidence that any specific textile in Hildesheim served to shape local memory, the pictured curtain behind the Virgin does resemble the other objects just analyzed in that it acts as a portal. It does so not only pictorially, by means of its similarity to the altar curtain and roof depicted on the left folio, but also metaphorically. The association of a curtain with Mary plays into a complicated semiotic system within which medieval theologians understood curtains to operate. Compared to the concealing temple curtain of the Old Testament, the curtain in the New Testament was said to mark the path to the secrets of the heavens revealed by Christ’s Incarnation: “Having therefore, brethren, a confidence in the entering into the holies by the blood of Christ; A new and living way which he hath dedicated for us through the veil, that is to say, his flesh” (Hebrews 10:19–20). In this passage, Christ’s flesh is linked to the veil of the tabernacle that Christians penetrated when they consumed Christ’s body during the sacrament of the Eucharist. From this idea developed figurative language that associated the temple curtain with the flesh of Christ, resulting in the increased pictorial presentation, in early medieval art, of the curtain motif in depictions of the Incarnation and of the Virgin. The metaphorical fusion of the curtain and Christ’s body crystallized in Western thought during the eleventh century.

Indeed, the curtain-flesh trope appeared frequently in the Ottonian period, even outside exegetical commentary. In her poem on Mary, the nun Hrotsvit, for example, referred to Christ’s Incarnation as the covering of his divine nature with a veil of human form. The picture of the Baptism in the Bernward Gospels (fol. 174v; plate 15) presents the same idea in a painting. Standing to each side of Christ, two angels hold open a white curtain with a gold border. Its color and V-pattern closely resemble the shading of Christ’s body, thus visually linking the two. By means of this association, the curtain becomes not only the portal and conduit to the sacred but also, and at the same time, a metaphorical membrane in which the divine manifests its presence.

A peculiar detail emphasizes the extent to which their nature—as both portals and membranes in the mode of Christ’s incarnate and sacramental body—informs the selection of the objects reproduced in the dedicatory painting, the manner of these works’ depiction, and their resulting symbolic power. On the left folio, the church in which Bernward stands includes two central rows of windows. The lower one, at the clerestory level, is painted gold and silver; it reads as part of the metallic patterning that repeats over the surface of the page. These windows appear impermeable to the eye.

In contrast, the representation of the three windows in the gable suggest a sense of transparency. Lines around the central window frame its arch. These begin at the top of the window and split along a vertical part into two groups of parallel lines that curl around the window, creating a pattern that resembles hair and suggestively conjures the impression of a face in the window (fig. 9).58 There is only scattered evidence for the presence of historiated windows in Germany in the Carolingian and Ottonian period.59 Although archeological research indicates the presence of fragments of colored glass in Europe since at least the sixth century, it remains difficult to reconstruct what such fragments originally depicted.60 Extant eleventh-century glass panels that may have portrayed a figure offer only inconclusive evidence.61 In Germany, two late eleventh-century roundels from Lorsch and Wissenbourg have been restored. Each portrays a bearded man, but other reconstructed details in the windows are disputed, so that identifying the subjects of these panels remains a contentious issue.62

Despite the lack of material evidence, however, numerous medieval texts associate Christ with glass and suggest that the hair around the painted window may be intended to visualize metaphors that compare the passage of light through a window to the Incarnation. Two sermons that were attributed to Augustine in the Middle Ages popularized this trope.63 The concept’s importance in fashioning eleventh-century discourse about the Incarnation is attested to by its appearance in a German vernacular poem by the end of that century. A verse addressed to the Virgin summarizes the metaphor: “Since you gave birth to the Child, you were wholly stronger and virgin from the companionship of man. If this seems impossible, consider glass, to which you are similar. The sunlight appears through the glass; it is twinkling and stronger than it was before; through the blinking glass it enters the house dispelling darkness. You are the blinking glass through which comes the light, which takes the darkness from the world. From you shines the light of God in all lands.”64 In this passage, the poet associates the window with the Virgin’s body, while the light that shines through the glass is Christ. When these lines are considered against all the other textual and pictorial references to the Incarnation in the bifolium, it becomes highly probable that the window framed by hair pictorially renders Christ’s Incarnation in matter.

On the one hand, to the extent that the glass serves as the material support that gives visible shape to the divine light, the window, like both the curtain and reliquary statue of the Virgin, contains and transmits the sacred. On the other hand, the glass acts also in the reverse direction, like doors, as a mediating portal between Bernward’s church and the divine. The two rows of windows—one a transparent membrane that models the Incarnation, and the other reflective, and blocking—in effect resemble the works reproduced on the right folio (doors, curtain, statue) in their capacity to be either active/open/revealing or still/closed/concealing. These both evoke actual works of art from Hildesheim and share the same symbolic power to mediate the sacred via a process allegorically related to Christ’s Incarnation.

A series of objects with similar characteristics appears on the left folio, primarily around the altar. The most easily identifiable works are the five golden candleholders with a triangular base and silver knobs that surround the altar. They reflect the shape and material of a pair of candlesticks that were discovered in Bernward’s tomb in the twelfth century and bear an inscription naming the bishop.65 Drawn more generically, as types, the chalice, paten, portable altar, and various textiles on the left folio offer more conventional depictions of common ecclesiastical objects. Yet these too may index products of Bernward’s patronage. According to his biographers, Bernward donated several chalices and patens to Saint Michael’s.66 Additionally, a portable altar from the cathedral treasury is connected by figural style and iconography to the Bernward Gospels.67 Where the golden object displayed on the main altar in the painting includes a series of silver arches on the front face, however, the extant portable altar in Hildesheim features niello engravings on gold-plated silver. Two additional objects decorated in a manner similar to the painted portable altar appear in other miniatures of the Bernward Gospels: an Adoration scene that follows the dedication painting (fol. 18r; plate 4) and the first illustration to the gospel of John (fol. 174r; plate 14). These further examples underscore that, just as for the objects of the right folio, the artworks on the left folio are reproduced to varying degrees of verisimilitude and specificity.

The works depicted on the left folio are centered around a particular category of objects, the vasa sacra, which form part of the material instruments of the Mass; this made them sites of mediating power. During the Mass the vasa sacra served symbolically to mark God’s presence in the church. Among these the chalice and paten were particularly significant for coming into direct contact with the sacramental body of Christ. As such, the vasa sacra stood at the threshold between the visible and invisible, the material and the immaterial. In the painting they key the multidirectional communication with God in which the reproduced artworks participate. That linking of sacrament with vasa sacra and other objects in the church developed essentially from medieval liturgical habits.

Similar ideas underlay the offertory procession, which, until the middle of the eleventh century, took place at the beginning of the Mass. During this procession, the congregation presented gifts to the altar. Subsequently, before the recitation of the Canon, which contained prayers specific to the host, the priest would perform the secreta, where he asked God to accept and sanctify the congregation’s offerings.68 Then, during the Canon, the celebrant would pray that the consecrated host be raised to heaven and blessed by God, thus ritually connecting the gifts to an act of transformation. Contemporary monastic preambles to donation records draw on this liturgical association between the offering and the Eucharist in order to explain that the effectiveness of a gift depended on its being transformed at the altar.69 By this process the object was converted from an earthly good to something accepted by God, giving proof of the donor’s merit. That potential for transformation and divine acceptance invested the offerings with the capacity to bridge the gap between earth and heaven. When such gifts were then employed in ecclesiastical rituals—whether because they were themselves liturgical objects, such as, for example, chalices, reliquaries, textiles, and certain types of books, or because they were to be added to a liturgical object, such as a gem placed on a reliquary—that power was amplified.70 By merging the representation of a dedicatory act with references to the Eucharistic ritual, the painting reinforces the place of objects at the nexus of Bernward’s communication with God.

A painting in the contemporary Uta Codex (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Codex Latinus Monacensis 13601) elaborates themes similar to the Bernward Gospels; it offers a useful comparison that clarifies what is at stake in the depiction of objects in the Bernward Gospels. Made for the nunnery of Niedermünster in the 1020s, the Uta Codex contains painted reproductions of objects from the treasury of a neighboring male monastery dedicated to Saint Emmeram.71 These appear in a bifolium showing, on the left, a symbolic crucifixion, and on the right, the bishop-saint Erhard celebrating the Mass (fols. 3v–4r; fig. 10). As Adam Cohen has analyzed this miniature extensively in his monograph on the Uta Codex, I will here only summarize those aspects of the painting most relevant to the dedication of the Bernward Gospels.72

First, the miniature in the Uta Codex portrays a liturgical act. Erhard wears the vestments of a priestly celebrant—in this case, the Jewish high priest of the Old Testament. Both bishops direct their gaze forward across an altar to the opposite folio. By raising the book in both hands, Bernward both offers the codex to the saints and raises the book before the altar as if to perform a ritual; Erhard is depicted frontally, in an orans posture, and the presence of the deacon beside him frames the scene primarily as a liturgical event.

Second, the altar stands at the center of Erhard’s ritual and intercessory actions directed toward Christ, who appears in a symbolic Crucifixion on the opposite folio. The paintings’ geometric structure and the architectural patterns in the inner border of each half of the opening link the pictures to each other. The gaze of both the deacon and Saint Erhard create a movement from right to left that directs attention to the Crucifixion. There, at the level of the altar on Erhard’s page, the personification of Synagoga moves away from Christ, contrasting sharply with the direction of Erhard and the deacon’s attention. Tituli in the opening address the targeted audience of the work, the nuns of Niedermünster, ordering them to learn and strive after the virtues represented by the paintings, presupposing the audience’s contemplation of the page and Erhard’s role as a mediator between them and Christ.73

The Erhard miniature also incorporates a group of golden objects that can be identified with works from the treasury of the monastery of Saint Emmeram in Regensburg. These were gifts from the ninth-century emperor Arnulf of Carinthia and they are described in a life of Saint Emmeram written within ten years of the Uta Codex.74 The most recognizable of the reproduced objects is a portable altar known as the Arnulf ciborium; it is the two-level structure surmounted by a crossing triangular roof that appears in the middle of the altar.75 Beside the painted ciborium is a book, drawn quite conventionally, perhaps a reference to the renowned Codex Aureus of Saint Emmeram (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 14000). A chalice and paten appear just before the ciborium and are also quite generic in their appearance—they correspond to donations cited in the slightly later text. A walled complex depicted below the altar probably represents Arnulf’s royal palace, one of the monastery’s properties, while the object that hangs above the altar may be Arnulf’s royal crown. In front of the altar is a Sassanian or Byzantine silk decorated with medallions that show facing winged horses. Although no such textile survives at Saint Emmeram today, the biographical text notes that Arnulf gave the community colored cloths and, as Cohen has pointed out, dotted medallions are a common ninth-century textile motif.76 Moreover, because precious patterned silks were frequently used for burial or to cover relics, they rarely survive intact to the present day.77

These objects bridge the space between the bishop-celebrant and God not only formally, because they appear between the bishop-celebrant and the Crucifixion, but also symbolically. Cohen argues that a complex pseudo-Dionysian process underlies the page’s design, in which the golden objects serve to transport the viewer anagogically from the material world to the immaterial contemplation of the divine.78 By doing so, the miniature positions the objects of the treasury on the threshold between the earthly and heavenly, and they thus become sites of communication and presence. Such a focus on material objects as mediating membranes duplicates the ideas developed in the Bernward Gospels dedication painting, which, however, draws on metaphors for the Incarnation and liturgical habits rather than on philosophical concepts in order to convey the objects’ power.

Further similarities include the fact that the painting reproduces known works of art to varying degrees of verisimilitude. Although the Arnulf ciborium is readily identifiable because of its shape and material, the chalice, paten, book, and crown are quite generic. In contrast, the silk by the altar is reproduced in large format as if to ensure that it would be recognized by its specific pattern, although the textual descriptions of Arnulf’s colored cloths offer no indication of the textiles’ decoration. Moreover, the artworks selected to be reproduced in both manuscripts played an active role in the shaping of communal memory, both individually and as a group. This has already been established for the dedicatory bifolium in the Bernward Gospels, and Cohen explains how the citation of these objects in Saint Emmeram’s slightly later biography served as part of that text’s larger project to resist the episcopal authority being exerted over the monastery by the local bishops.79 The careful attention paid to Arnulf’s gifts in this document suggest that they were particularly important carriers of memory in that project.

Why reproduce treasury objects from a neighboring male monastery in a book made for the nuns of Niedermünster? Cohen offers a variety of possible explanations, but most important for our understanding of the Bernward Gospels is his suggestion that the miniature can be read as a recapitulation of Abbess Uta’s reform of Niedermünster, which had earlier been a house of canonesses.80 By gazing at the miniature, the future abbesses and nuns of Niedermünster, who are addressed directly by the tituli, remember the institution’s new, reformed identity.81 Did the objects play a role in that process? Since they originated in the monastery of Saint Emmeram, which charged Uta with reforming the nunnery, they were works of art that, like the figure of Saint Erhard himself, represented a past better suited to the community’s reformed present. Perhaps in that way were the nuns to forget that they had ever been a house for canonesses.82

Underscoring that the simulated objects play a commemorative function is that they are treasury objects, and what the parallels between the Bernward Gospels and Uta Codex further make clear is that by displaying a group of simulated objects, each highlighted for their precious and symbolic materials but only sparsely identified, these Ottonian miniatures deliberately translate a construct that would have been very familiar to medieval audiences: the treasury list. One such inventory from the Hitda Codex (Darmstadt, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, HS1640), dating to the first third of the eleventh century, provides a useful comparative example. The document (fol. 1v) lists objects added to the treasury of Meschede, in the Cologne diocese, by a certain Abbess Hitda.83

The wandering Hitda, guardian of this place, gave these offerings to God and Saint Walburga on behalf of herself and her own in accordance with a vow. Crosses: III, decorated with gold and precious stones and one out of gold and ivory. A statue of holy Mary made with gold and precious stones and wearing a small cloak. Book: I with gold and gems, and two golden. Golden censer: I. Banners: IV. Ampullas: III, one onyx, II crystal. Napkins: III. Chasuble: I with silk and a gold stole. III icons. Three caskets. Hangings: II. Curtains: III. One leather. Small vessels: II for the use of the sacrifice, one of precious stones and the other of ivory. Pillows: III scarlet ones for the purpose of carrying books. If anyone should remove or reduce any part from the holy use, let them be cursed.84

Hitda’s portrait follows just a few folia after this text (fol. 6r). There the abbess stands directly before Saint Walburga, supporting a proffered codex with both hands.85 The saint responds by grasping the book at its top edge with her right hand. The miniature portrays the two unusually close, standing in the same space and not only linked through their hold on the book but also through their gaze.

As in the Bernward Gospels and Uta Codex, the object that serves as the site of Hitda’s inventory also mediates her communication with the saint. In one of the better known miniatures of this codex, the painting of Christ in Majesty,86 the power of the manuscript to serve as material host in a reciprocal process of communication between earth and heaven is established by a titulus on the facing page: “this visible product of the imagination represents the invisible truth whose splendor penetrates the world through the two-times-two lights of the new doctrine.” The term “imagination” here (imaginatum in the Latin) implies a dynamic process in which the viewer moves from the image to the contemplation of the divine and back again.87

Hitda’s treasury list also illustrates a characteristic feature of such documents—the way in which their format serves to emphasize the treasury’s accrued value. Medieval inventories repetitively enumerate the number and type of objects along with their luxurious materials (in Hitda’s inventory: gold, gems, ivory, and silk). In so doing the texts convey the treasury’s formal qualities as a subtly varied group of related objects whose dominant characteristics are preciousness and material similarity. The dedicatory painting in the Bernward Gospels shares these formal features with Hitda’s text. Textile patterns decorate the painting’s background, serving to create flat surfaces of delicately varying colors that present the illusion of silken parchment.88 The effort to produce that effect is especially apparent on the left folio, where the choice of color and pattern in Bernward’s green chasuble causes the figure to blend somewhat into the green patterned ground. Over the opening’s silken surface accrues gold and silver, which create a shimmering and subtly varying effect. Together, these real and simulated materials contribute to the thesaurization of the page.89 By means of this display of accumulated wealth, the painting underscores the actual and symbolic value of the treasury, both of which informed how medieval donors and recipients understood the gift-giving process through which medieval treasuries were constituted.90

As a depository of both monetary and symbolic capital, the medieval treasury had the capacity to carry memoria. Yet the early medieval treasury was essentially a mass of miscellaneous gifts.91 Consequently, its commemorative associations depended on how the gifts’ recipients shaped the meaning of that mass. In 1967, Bernhard Bischoff edited 151 documents from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries that pertain to the treasuries of diverse religious communities.92 For the most part, the texts drafted for that purpose state that they record the treasury in its contemporary form, using variations of hic est thesaurus (this is the treasury) or, quite commonly, commemoratio, literally “commemoration” of the treasury. A few rare cases emphasize that the documents act as the testimony of a witness by using verbs for “to see,” videbatur (for example, no. 46), or “to discover/find” (no. 96). Some include formulas such as augmentabantur (augmented), indicating a subgroup of the treasury added under the most recent abbacy or episcopacy (nos. 17, 25, 44, 76).

All these documents also follow the conventions described earlier. They index objects in an abbreviated format that emphasizes the number and material for each category of object, underscores the treasury’s value, and only occasionally includes contextual information such as an object’s function or the name of a donor. Moreover, despite their claims to the contrary, these documents do not serve as unproblematic records. Rather, they are attempts to construct memory, especially by the Ottonian period, when treasury inventories were more commonly written by the treasury’s owners than in earlier times.93 These owners selectively list works from the treasury, in effect collecting them, and narrate the resulting group of objects in ways that serve the community’s contemporary purposes.94

Constantly in flux as communities received goods and then recirculated them, treasuries offered donors and recipients numerous opportunities not only for making but also for changing memory—a process that required the creation of a “record” of some kind. Although such records depended to some extent on objects’ actual preexisting commemorative associations, they also worked to structure those associations’ meaning, readily eliding, shifting emphasis, perhaps deliberately confusing, and even sometimes entirely inventing them.95 Donors had to understand that in that process, their commemoration hinged on the capacity of their gifts to project, fix, and stabilize their image and presence in the recipients’ memory not only in the present, but also in the future.

Such manipulations of the treasury record to shape memory relate closely both to medieval mnemotechnic and commemorative practices, the mental picturing of the thesaurus as an organizational system being a fundamental process in the creation of both types of memory and composition, inventio being memory’s most vital tool.96 Medieval records of the treasury and its donors thus employ a cognitive structure that, because it is reused, continuously performed, and linked to sacred objects, has the potential to fix communal memory. Yet that memory remains something that is inherently disorganized and unstable.97 Against that background, each new instance of creating a treasury list must be understood in two ways: first, as an attempt to establish and fix memory at a particular moment in time, and second, as a practice meant to maintain this memory in concrete things, objects that existed outside of the record itself. By picturing the treasury, the Bernward Gospels aimed both to create the memory of a moment of great personal significance to the bishop—the foundation of Saint Michael’s Abbey together with the offering of the gospels—and to prompt a commemorative response from the monks which might stabilize that memory.

In sum, the dedication painting explores multiple themes: from the praxis of memoria to the exegetical treatment of Christ’s Incarnation; from expectations about gift-giving to ideas about the Eucharist; and from views of the relationship between the earthly and the heavenly church to notions about the power of cult objects as sites for the entry of spirit into matter. In so doing, the painting displays three main characteristics. It combines the picture of a donation scene with Mass imagery; it represents signs for Christ’s incarnate body as manufactured objects that operate in the mode of the Eucharist; and it translates the treasury list into painted form.

Each of these iconographic choices relate to ideas about gift-giving pro anima. While gift exchange took many forms in the Middle Ages, the medieval offering pro anima specifically served to negotiate social and spiritual bonds between donors and at least two recipients: the earthly religious communities that took ownership of the gift and the heavenly community of saints to whom the gift was dedicated. The goal was to set into motion mechanisms and actors that would guarantee the donor a place in heaven. That process was structured around the idea that mankind might gain eternal rewards by making offerings to the divine. The gift pro anima is thus fundamentally preoccupied with the donor’s salvation and draws particular charge from the early medieval liturgical habit of linking offerings to the consecration of the Eucharist and from the praxis of memoria.98 The painting depicts Bernward as both the Mass celebrant and the founder of Saint Michael’s, surrounded by the products of his artistic patronage; it memorializes the bishop’s exceptional patronage, placing him simultaneously before the altar of the monastic foundation where he would be buried and at the threshold of the heavenly church, the bishop’s hoped-for eternal reward. Achieving that reward requires the commemorative and intercessory prayers of the monks of Saint Michael’s. The dedicatory painting effects the symbolic transformation of the Bernward Gospels itself into treasure, both to fix a personal moment and to stabilize the bishop’s image and presence in the monks’ memory for present and succeeding generations.